The European Conceptual History Project (ECHP): Mission Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society (IECON 2021)

Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society (IECON 2021) Special Session on “High Power Multilevel Converters: Topologies, Combination of Converters, Modulation and Control” Organized by Principal Organizer: Alain Sanchez-Ruiz ([email protected]) Affiliation: Ingeteam R&D Europe Organizer 1: Iosu Marzo ([email protected]) Affiliation: University of Mondragon Organizer 2: Salvador Ceballos ([email protected]) Affiliation: Basque Research and Technology Alliance (BRTA) - Tecnalia Organizer 3: Gonzalo Abad ([email protected]) Affiliation: University of Mondragon Alain Sanchez-Ruiz (SM’20) received the B.Sc. degree in electronics engineering, the M.Sc. degree in automatics and industrial electronics, and the Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering from the University of Mondragon, Mondragon, Spain, in 2006, 2009, and 2014, respectively. He joined Ingeteam R&D Europe, Zamudio, Spain, in May 2014, where he is currently an R&D Engineer. Since January 2017, he has also been a Lecturer with the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain. From February 2012 to May 2012 he was a Visiting Researcher at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA. His current research interests include modelling, modulation and control of power converters, multilevel topologies, advanced modulation techniques, high- power motor drives and grid-tied converters. Iosu Marzo was born in Bergara, Spain, in 1995. He received the B.S. degree in Renewable Energies Engineering, and the M.S. degree in the Integration of Renewable Energies into the Power Grid, both from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Spain, in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Since 2018, he has been with the Electronics and Computer Science Department at the University of Mondragon, Mondragon, Spain, researching in the area of Power Electronics 1 Good quality papers may be considered for publication in the IEEE Trans. -

Cinema As a Transmitter of Content: Perceptions of Future Spanish Teachers for Motivating Learning

sustainability Article Cinema as a Transmitter of Content: Perceptions of Future Spanish Teachers for Motivating Learning Alejandro Lorenzo-Lledó * , Asunción Lledó and Gonzalo Lorenzo Department of Development Psychology and Teaching, Faculty of Education, University of Alicante, 03690 San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (G.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 May 2020; Accepted: 6 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: In recent decades, the diverse changes produced have accelerated the relationships regulated by media. Cinema was able to bring together moving image and sound for the first time, and as a result of its audiovisual nature, it is a particularly suitable resource for motivation in education. In this light, the teacher’s perception for its application in its initial formal stage is highly relevant. The main objective of our research, therefore, has been to analyze the perceptions of cinema as a didactic resource for the transmission of content in preschool and primary education by students who are studying to become teachers themselves. The sample was composed of 4659 students from Spanish universities, both public and private. In addition to this, the PECID questionnaire was elaborated ad hoc and a comparative ex post facto design was adopted. The result showed that over 87% of students recognized the diverse educational potentialities of cinema, with motivation being an important factor. Furthermore, significant differences were found in perceptions according to different factors such as the type of teacher training degree, the Autonomous Community in which the student studied, as well as film consumption habits. -

Reform and Responsibility — the Climate of History in Times of Transformation Aalborg Nordic History Congress, Keynote 17 August 2017

HISTORISKarticle TIDSSKRIFT 10.18261/issn.1504-2944-2018-01-02Bind 97, nr. 1-2018, s. 7–23 artikkel ISSN online: 1504-2944 ARTIKKEL 10.18261/issn.1504-2944-2018-01-02 Reform and responsibility — the climate of history in times of transformation Aalborg Nordic History Congress, Keynote 17 August 2017 Sverker Sörlin Fil.dr. 1988. Professor ved Avdelningen för historiska studier av teknik, vetenskap och miljö, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Stockholm. [email protected] Dear colleagues, students, friends! It is a great pleasure to see you all here, a distinguished audience of Nordic historians, hono- ring this hour with your presence. For me it is a privilege. This is a congress I hold dear. In times when international conferences have grown in size and numbers I have always thought it is immensely valuable to keep the Nordic community of historians alive and well, not for nostalgic reasons but because “Nordic” is an appropriate level of focus and analysis. Shortly before traveling here I finished the concluding chapter for a book with a Nor- wegian publisher on the tradition of Folkeopplysning in the Nordic countries since the 17th century.1 One of my ongoing papers right now is an analysis of the influence in our region of the famous Berkeley historian of science, environment and feminism, Carolyn Merchant.2 Other contributors to that book write of other themes, I write of the Nordic countries. I can swear she had some influence since I took a PhD course for her at Umeå University in 1984, but I am confident there is more…! Nordic is real. -

Spanish Arts and Gastronomy

1 UC REAL-2016 SUMMER PROGRAMS SPANISH LANGUAGE AND CULTURE Program Director: Prof. Dr. Jesus Angel Solórzano, Dean, UC Faculty of Arts and Humanities Program Coordinator: Prof. Dr. Marta Pascual, Director of the UC Language Center (CIUC) This Program is intended to offer all REAL students full immersion into the Spanish way of life, and combines the learning of Spanish Language with sessions on Spanish History, Arts, and Gastronomy. The program is scheduled so that it can be taken in combination with any of the other three. It includes Spanish Grammar and Conversation classes in the afternoons, as well as Friday morning sessions on Spanish Art and History, including guided excursions to relevant historical sites of Cantabria, and practical Spanish Gastronomy sessions on Wednesday nights. All classes will be taught in Spanish and groups will be made according to the results of a language placement test. Spanish Culture sessions, taught in an easy to follow Spanish, will be common to all students and beginners will be assisted by their instructors. Academic load: 52 contact hours (32 hours of Spanish Language, plus 20 hours of Spanish Culture sessions) Subjects included: • Spanish Language for foreigners: Monday through Thursday, 3-5 pm • Spanish Art and History Sessions: Fridays (3, 10 and 17 June), from 9 am to 1 pm • Spanish Gastronomy. Practical Sessions. all Wednesdays, out of scheduled classes UC REAL Summer Programs http://www.unican.es/en/summerprograms 2 Spanish Language for foreigners The University of Cantabria Language Center (CIUC) has offered summer courses in Spanish as a Foreign Language for well over two decades. -

Editorial Acknowledgement

Editorial Acknowledgement The Editor and Associate Editors would like to warmly thank the editorial board and colleagues who kindly served as reviewers in 2016. Their professionalism and support are much appreciated. EDITORIAL BOARD Ivon M. Arroyo, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, USA Tiffany Barnes, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, USA Joseph E. Beck, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, USA François Bouchet, Sorbonne Université, FRANCE Kristy Elizabeth Boyer, University of Florida, USA Cristina Conati, University of British Columbia, CANADA José Pablo González-Brenes, Pearson, USA Neil T. Heffernan, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, USA Roland Hübscher, Bentley University, USA Judy Kay, University of Sydney, AUSTRALIA Kenneth R. Koedinger, Carnegie Mellon University, USA Irena Koprinska, University of Sydney, AUSTRALIA Brent Martin, University of Canterbury, NEW ZEALAND Taylor Martin, Utah State University, USA Manolis Mavrikis, University of London, UNITED KINGDOM Gordon I. McCalla, University of Saskatchewan, CANADA Bruce M. McLaren, Carnegie Mellon University, USA Tanja Mitrovic, University of Canterbury, NEW ZEALAND Jack Mostow, Carnegie Mellon University, USA Rafi Nachmias, Tel-Aviv University, ISRAEL Zachary A. Pardos, University of California at Berkeley, USA Radek Pelánek, Masaryk University, CZECH REPLUBLIC Kaska Porayska-Pomsta, University of London, UNITED KINGDOM Peter Reimann, University of Sydney, AUSTRALIA Cristóbal Romero, University of Cordoba, SPAIN Carolyn Penstein-Rosé, Carnegie Mellon University, USA -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE TEOFILO F. RUIZ Address: 1557 S. Beverly Glen Blvd. Apt. 304, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Telephone: (310) 470-7479; fax 470-7208 (fax) E-mail: [email protected] HIGHER EDUCATION: City College, C.U.N.Y., B.A. History, Magna Cum Laude. June 1969 New York University, M.A. History Summer 1970 Princeton University, Ph.D. History January 1974 TEACHING CAREER: Distinguished professor of History and of Spanish and Portuguese 2012 to present • Faculty Director, International Education Office 2010-2013 • Chair, Department of Spanish and Portuguese 2008 to 2009 • Professor of History, University of California at Los Angeles 1998 to 2012 • Visiting Professor for Distinguished Teaching, Princeton University 1997-98 • Professor, Department of History, Graduate Center, C.U.N.Y. 1995-98 • Tow Professor of History at Brooklyn College 1993-95 • Director of The Ford Colloquium at Brooklyn College 1992-95 • Visiting Professor, Princeton University, Spring 1995 • Visiting Martin Luther King Jr. Professor, Michigan State University Spring 1990 • Visiting Professor, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) Winter 1990 • Professor of History, Brooklyn College 1985-98 • Professor of Spanish Medieval Literature, Ph.D. Program in Spanish and Portuguese, Graduate Center, C.U.N.Y. 1988-98 • Associate Professor, History, Brooklyn College 1981-85 • Visiting Assistant Professor, History, Princeton University Spring 1975 • Assistant Professor, History, Brooklyn College 1974-81 • Instructor, History, Brooklyn College 1973-74 • Teaching Assistant, History, Princeton University Spring 1973 HONORS, FELLOWSHIPS, ELECTIONS, AND LECTURESHIPS: Doctor Honoris causa: University of Cantabria (Spain), April 2017 Festschrift, Authority and Spectacle in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Essays in Honor of Teofilo F. -

History 2016 Contents

History 2016 CONTENTS Historiography ..................................................................................1 Skills/Sources ...................................................................................3 Heritage ..............................................................................................5 Medieval History .............................................................................7 Early Modern History.................................................................. 13 Irish History ..................................................................................... 19 French History .............................................................................. 22 Social History ................................................................................ 24 Science, Technology & Medicine ......................................... 25 History of War ............................................................................... 29 Political History ............................................................................. 31 Gender ..............................................................................................36 Imperialism .....................................................................................39 Cultural History ............................................................................45 Journals ............................................................................................. 51 Agents, representatives and distributors ........................ 52 Index -

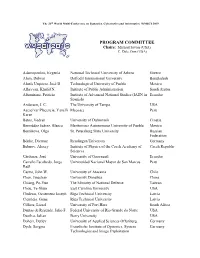

PROGRAM COMMITTEE Chairs: Michael Savoie (USA) C

The 23rd World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics: WMSCI 2019 PROGRAM COMMITTEE Chairs: Michael Savoie (USA) C. Dale Zinn (USA) Adamopoulou, Evgenia National Technical University of Athens Greece Alam, Delwar Daffodil International University Bangladesh Alanís Urquieta, José D. Technological University of Puebla Mexico Alhayyan, Khalid N. Institute of Public Administration Saudi Arabia Altamirano, Patricio Institute of Advanced National Studies (IAEN in Ecuador Spanish) Andersen, J. C. The University of Tampa USA Ascacivar Placencia, Yanelli Mecoacc Peru Karen Batos, Vedran University of Dubrovnik Croatia Bermúdez Juárez, Blanca Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla Mexico Bernikova, Olga St. Petersburg State University Russian Federation Bönke, Dietmar Reutlingen University Germany Bubnov, Alexey Institute of Physics of the Czech Academy of Czech Republic Sciences Cárdenas, José University of Guayaquil Ecuador Carreño Escobedo, Jorge Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Peru Raúl Castro, John W. University of Atacama Chile Chen, Jingchao University Donghua China Chiang, Po-Yun The Ministry of National Defense Taiwan Chou, Te-Shun East Carolina University USA Chukwu, Ozoemena Joseph Riga Technical University Latvia Ciemleja, Guna Riga Technical University Latvia Cilliers, Liezel University of Fort Hare South Africa Dantas de Rezende, Julio F. Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte USA Dasilva, Julian Barry University USA Doherr, Detlev University of Applied Sciences Offenburg Germany Dyck, Sergius Fraunhofer Institute of Optronics, System Germany Technologies and Image Exploitation Edwards, Matthew E. Alabama A&M University USA Eremina, Yuliya Riga Technical University Latvia Fagade, Tesleem University of Bristol UK Farah, Tanjila North South University Bangladesh Florescu, Gabriela National Institute for Research and Development Romania in Informatics Fries, Terrence P. -

Historians' Orientations and Historical Production

Kasvatus & Aika 5 (1) 2011, 7–18 Mapping historians: historians' orientations and historical production Lisa Muszynski and Jyrki Reunamo Narrative historians have long exhibited greater or lesser awareness of their own agency as authors, where absolute objectivity is precluded. Indeed, historians' reports of the past include their own orientations or attitudes, which can also be examined in historians' autobiographies. In this article we present a study in which a questionnaire was used to ask historians about their orientations toward their subject matter. How do historians approach their work as agents and what might this reveal about the nature of historical production? In our model, we have distin- guished four criteria, sorted the answers using statistical analysis and weighed the results in the light of our expectations. Indeed, by exploring historians' presupposi- tions (exemplified in examining historians' autobiographies), historical production can be seen as an institutional process also steered by historians' orientations and agency with important philosophical implications for the integral relationship between historians' public and private roles. Introduction The reflexive questions concerning the historian's task, as presented in the questionnaire that serves as the basis of our study, is an approach designed to capture a particular matrix of historians' orientations and attitudes that serves to open up a tacit dimension in the pro- duction of history by the "historian as agent" (cf. Polanyi 2009 [1966]). In this article, -

Theory and Method Conceptual History

Helge Jordheim, University of Oslo To be published in Bloomsbury History: Theory and Method Conceptual History [9,000 – 10,000 words] 1. Introduction (c.500 words): w/ any basic definitions clarified At the most basic level, conceptual history is the history of words. These words, called “concepts” are of a specific kind, semantically richer, more ambiguous and thus more contested than those tasked with naming specific things in the physical world. The phrase itself is easily misunderstood, like other subgenres of historiography labelled in similar way. Just as there is nothing specifically “cultural” about cultural history, there is nothing particularly “conceptual” about “conceptual history” either. A more precise name would be “the history of concepts”, since “concepts” refer to the object of study rather than a carefully crafted analytics. Furthermore, many will consider “conceptual history” to be the translation of the German Begriffsgeschichte, which is also clearly the dominant tradition in the field, although by no means the only one. Thus, conceptual history has at least two meanings: in a more general sense, it studies how people have used words in changing historical contexts, with what meaning and purpose, drawing on a wide range of traditions, theories and methods, from etymology to text-mining; in a more specific sense, it refers to a set of theories and methods originating in post-war Germany at the interface between social history and intellectual history, and between hermeneutics and historicism, as well as to its main founder Reinhart Koselleck and the most decisive scholarly manifestation, the eight- volume lexicon Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe, published between 1972 and 1992. -

Ambivalence, Anxieties / Adaptations, Advances: Conceptual History and International Law

Martin Clark Ambivalence, anxieties / adaptations, advances: conceptual history and international law Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Clark, Martin (2018) Ambivalence, anxieties / adaptations, advances: conceptual history and international law. Leiden Journal of International Law, 31 (4). ISSN 0922-1565 (In Press) © 2018 Foundation of the Leiden Journal of International Law This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/89381/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. AMBIVALENCE, ANXIETIES / ADAPTATIONS, ADVANCES: CONCEPTUAL HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW MARTIN CLARK* Scholars of the history of international law have recently begun to wonder whether their work is predominantly about law or history. The questions we ask — about materials, contexts and movements — all raise intractable problems of historiography. And yet despite this extensive and appropriate questioning within the field, and its general inclination towards theory and theorising, few scholars have turned to the vast expanses of historical theory to try to think through how we might go about addressing them. -

(CONDCA) Disease Caused by AGTPBP1 Gene Mutations: the Purkinje Cell Degeneration Mouse As an Animal Model for the Study of This Human Disease

biomedicines Review The Childhood-Onset Neurodegeneration with Cerebellar Atrophy (CONDCA) Disease Caused by AGTPBP1 Gene Mutations: The Purkinje Cell Degeneration Mouse as an Animal Model for the Study of this Human Disease Fernando C. Baltanás 1,* , María T. Berciano 2, Eugenio Santos 1 and Miguel Lafarga 3 1 Lab.1, CIC-IBMCC, University of Salamanca-CSIC and CIBERONC, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Molecular Biology and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), University of Cantabria-IDIVAL, 39011 Santander, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), University of Cantabria-IDIVAL, 39011 Santander, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923294801 Abstract: Recent reports have identified rare, biallelic damaging variants of the AGTPBP1 gene that cause a novel and documented human disease known as childhood-onset neurodegeneration with cerebellar atrophy (CONDCA), linking loss of function of the AGTPBP1 protein to human neurode- Citation: Baltanás, F.C.; Berciano, generative diseases. CONDCA patients exhibit progressive cognitive decline, ataxia, hypotonia or M.T.; Santos, E.; Lafarga, M. The muscle weakness among other clinical features that may be fatal. Loss of AGTPBP1 in humans Childhood-Onset Neurodegeneration recapitulates the neurodegenerative course reported in a well-characterised murine animal model with Cerebellar Atrophy (CONDCA) harbouring loss-of-function mutations in the AGTPBP1 gene. In particular, in the Purkinje cell degen- AGTPBP1 Disease Caused by Gene eration (pcd) mouse model, mutations in AGTPBP1 lead to early cerebellar ataxia, which correlates Mutations: The Purkinje Cell with the massive loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells.