Downloaded 4.0 License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

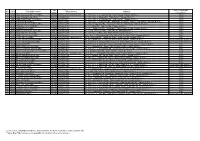

No. Area Post Office Name Zip Code Telephone No. Address Same Day

Zip Same Day Flight No. Area Post Office Name Telephone No. Address Code Cutoff Time* 1 Yilan Yilan Jhongshan Rd. Post Office 26044 (03)9324-133 (03)9326-727 No. 130, Sec. 3, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:30 2 Yilan Yilan Jinlioujie Post Office 26051 (03)9368-142 No. 100, Sec. 3, Fusing Rd., Yilan 260-51, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:10 3 Yilan Yilan Weishuei Rd. Post Office 26047 (03)9325-072 No. 275, Sec. 2, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-47, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:20 4 Yilan Yuanshan Post Office 26441 (03)9225-073 No. 299, Sec. 1, Yuanshan Rd., Yuanshan Township, Yilan County 264-41, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:50 5 Yilan Yuanshan Neicheng Post Office 26444 (03)9221-096 No. 353, Rongguang Rd., Yuanshan, Yilan County 264-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:40 6 Yilan Yilan Sihou St. Post Office 26044 (03)9329-185 No. 2-1, Sihou St., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:20 7 Yilan Jhuangwei Post Office 26344 (03)9381-705 No. 327, Jhuang 5th Rd., Jhuangwei, Yilan County 263-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:00 8 Yilan Yilan Donggang Rd. Post Office 26057 (03)9385-638 No. 32-30, Donggang Rd., Yilan 260-57, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 12:10 9 Yilan Yilan Dapo Rd. Post Office 26054 (03)9283-195 No. 225, Sec. 2, Dapo Rd., Yilan 260-54, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 11:40 10 Yilan Yilan University Post Office 26047 (03)9356-052 No.1, Sec. -

Yilan! Here Are Some Things That We Think You Should Know About Our Wonderful City

Welcome to Yilan! Here are some things that we think you should know about our wonderful city. Things to do in Yilan County: Yilan Train Station and Jimmy Park(s): Downtown Yilan has a number of great public spaces designed in honor of Jimmy Liao, a famous Taiwanese children’s book illustrator from Yilan county. The Yilan Train Station and three nearby parks feature designs from his different books and are great places to go if you have a free afternoon. Lanyang Museum: Located in Toucheng, this museum details Yilan’s history and natural beauty. The building itself is architectural masterpiece, and is free for Yilan residents with an ARC. Yilan Museum of Art: Located in the old Bank of Taiwan building, the Yilan Museum of Art changes its exhibits frequently, so there is always something new to see. Directly across the street is also the former home of the Japanese magistrate during the days of colonization. This is a place to learn some of that history pertaining to Yilan. This museum is also free for Yilan residents once you have an ARC. Taiwan Theater Museum: If you are interested in Chinese opera, be sure to keep an eye out for this museum, which showcases a certain type of Taiwanese opera. Gezai opera is the only type of traditional operas to actually originate in Taiwan. It is originally from Yilan County, so be sure to check it out! While this museum showcases the Gezai opera, it also has exhibits on traditional puppetry and offers a free costume loan service. Luodong Cultural Workshop: Located next to Dongguan Junior High School, the Luodong Cultural Workshop is home to orchestral performances of both traditional Chinese and western varieties; there is also a free museum at the top of this architecturally significant structure that features local art. -

Implementing Coastal Inundation Data with an Integrated Wind Wave Model and Hydrological Watershed Simulations

Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci., Vol. 23, No. 5, 513-525, October 2012 doi: 10.3319/TAO.2012.05.03.01(WMH) Implementing Coastal Inundation Data with an Integrated Wind Wave Model and Hydrological Watershed Simulations Dong-Sin Shih1, *, Tai-Wen Hsu 2, Kuo-Chyang Chang 3, and Hsiang-Lan Juan 3 1 Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute, National Applied Research Laboratories, Taichung, Taiwan 2 Department of Hydraulic and Ocean Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan 3 Water Resources Agency, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taipei, Taiwan Received 29 September 2011, accepted 3 May 2012 ABSTRACT Coastal inundation due to wave overtopping coastal structures and storm surges often causes serious damage and danger to the population of Taiwan. Ascertaining the areas that are prone to coastal inundation is essential to provide countermeasures for mitigating the problem. Simulations without precipitation are examined in this study since overtopping has been deter- mined to be a controlling factor in coastal flooding. We present scenarios for the simulation of coastal flooding with a unified wind wave and hydrological watershed model. The eastern coastal areas in Taiwan are selected as the study area. Simulations show that the resulting waves and tidal levels, generated by the Rankin-Vortex model and wind wave calculations, can be successfully obtained from the input data during wave overtopping simulations. A watershed model, WASH123D, was then employed for surface routing. The simulations indicate that the low-lying Yilan River and Dezikou Stream drainage systems were among the primary areas subject to inundation. Extensive inundation along both sides of the river banks was obtained in the case of extreme overtopping events. -

Yilan Handbook 2011-2012

About FSE The Foundation for Scholarly Exchange (formerly known as the U.S. Educational Foundation in the Republic of China), supported mainly by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education (MOE), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), and U.S. Department of State via the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT), is one of 51 bi-national/bilateral organizations in the world established specifically to administer the Fulbright educational exchange program outside the U.S. Ever since 1957, the Foundation has financed over 1400 Taiwan Fulbright grantees to the U.S. and more than 1000 U.S. Fulbright grantees coming to Taiwan. In 1962, the Foundation started the U.S. Education Information Center for Taiwan students who need information or guidance about studying in the U.S. Since 2003, the Foundation has cooperated with Yilan County Government to organize the Fulbright ETA project, with a view to providing high-quality English instruction to students in the county’s junior middle and elementary schools. Later, in 2008, the Kaohsiung City Government and the Foundation jointly began to deliver a similar ETA program in Kaohsiung. Currently, there are 28 Fulbright ETA grantees participating in this special project in both places. FSE is overseen by a Board of Directors comprising five Taiwanese and five U.S. members, with the director of the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) as the Honorary Chairman of the Board. The Fulbright Program The Fulbright Program was established in 1946 in the aftermath of WWII, as an initiative of Senator J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, who believed that a program of educational and cultural exchange between the people of the United States and those of other nations could play an important role in building lasting world peace. -

Taiwan Tourism Coupon Guide Book

Taiwan Tourism Coupon Guide Book Qinbi Village, Beigan Township, Matsu Travel Tips Travel Preface Travel Tips A land of beautiful scenery and warm human touch, Taiwan is blessed with the winds of freedom, a fertile land, and a sincere and kind-hearted people. Moreover, Taiwan ranks among the top 10 safest countries in the world. Pay attention to the following entry and visa information, and have a great trip to Taiwan! Entry Visa make purchases of at least NT$2,000 on the same day Taiwan, a Rarefrom the Verdant same designated stores Gem with the “Taiwan Tax There are four types of visas according to the Refund”-label is eligible to request the “Application purposes of entry and the identity of applicants: inside the Tropic of FormCancer for VAT Refund.” To claim the refund, they must 1. Visitor visa: a short-term visa with a duration of stay apply at the port of their departure from the R.O.C. of up to 180 days Taiwan, the beautiful island on the Pacificwithin Ocean, 90 daysis a rarefollowing verdant the dategem of among purchase, the and they 2. Resident visa: a long-term visa with a duration of countries that the Tropic of Cancer passes through.must take the purchased goods out of the country with stay of more thanTaiwan’s 180 days area accounts for only 0.03% of the world’s total area. However, Taiwan them. For further details, please visit the following 3. Diplomaticcontains visa substantial natural resources. Continuous tectonic movements have created websites: 4. Courtesy visacoastlines, basins, plains, rolling hills, valleys, and majestic peaks for the island and made it - http://www.taxrefund.net.tw Types of theabundantly duration endowof stay includewith mountains; 14-day, 30- over 200 of its peaks are more than 3,000 meters high, - http://admin.taiwan.net.tw day, 60-day, 90-day,making etc. -

The Diaoyu / Senkaku Islands Dispute

The Diaoyu / Senkaku Islands Dispute Questions of Sovereignty and Suggestions for Resolving the Dispute By Martin Lohmeyer A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Laws in the Faculty of Law, University of Canterbury 2008 Content Content ....................................................................................................................1 Acknowledgements..................................................................................................9 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................11 1.1. Emergence of the name of the islands ................................................................15 1.2. Location, topography, geological features and vegetation ...............................17 1.3. Legal question arising from this dispute............................................................21 1.3.1. Domestic Maritime legislation.................................................................................... 22 1.3.2. Legal Effect on national legislation of the Parties of dispute...................................... 22 2. Political Implications of the Conflict ...............................................................24 2.1. Diaoyu / Senkaku relation to oil..........................................................................24 2.2. Diaoyu Islands as a symbol for Sino-Japanese relations ..................................27 2.2.1. Diaoyu / Senkaku island as a proxy conflict .............................................................. -

Safe Community Monthly News Issue 42 January 2011

Department of Public Health Sciences Division of Social Medicine Safe Community Monthly News Issue 42 January 2011 In this issue DearColleagues,= WishyouaSaferNewYear,2011. NewCertifyingCentre 1 WeareproudtointroduceyouSafeCommunitiesin=Taiwan.= NewSafeCommunitydesignation = 2 WehavereportsfromCanada,Chile,Finland,Sweden&Taiwan. NewsfromFinland,Chile,Sweden= 1,2 Newsandreportsofthisissueareappendedbelow.Sameissueisalsoavail SCre8designation= 3 ableatourWHOCollaboratingCentreon=CommunitySafety=Promotionweb HealthEconomicsCourse 3 site:http://www.phs.ki.se/csp/who_newsletters_en.htm= Withwarmregards Call:SafeHospitalNetwork= 4 LeifSvanström,ResponsibleEditor= ForthcomingConferences= 4 KoustuvDalal,Editor= Europe opens a new and strong Certifying Centre! Inthebeginningofthisyearthetwoprevi ousCertifyingCentresinNorwayandSwe denisreplacedbyajointandnewCentre. LeifSvanströmischairing,MoaSundström isthecoordinatorandtheseniorcert ifiersareProfessorBörgeYtterstad,Har stad,Norway;DrBoHenricsson,Arjeplog, SwedenandMrGuldbrandSkjönberg,= Linköping,Sweden.Morecertifiersare abouttoberecruited.Correspondencewith MsMoaSundstrom,[email protected]. Reporter:LeifSvanstrom,Sweden. Photo:Sitting(LtoR)GuldbrandSkjönberg,Leif Svanström,MoaSundström,&KoustuvDalal. Standing:BörgeYtterstad,&BoHenricsson. Visit by a group of Directors from Beijing at Safe Community Head Quarter AgroupofhighprofiledirectorsleadbyMrYaoMeng visitedWHOCCCommunitySafetyPromotion,Karo linskaInstitutet,Swedenintwodaystrip.Theyhad exchangedknowledgeandattendeda2daysseminar onSafeCommunity.Leadingexpertsfromthefieldde -

PAYS SECTION Taiwan Produits De La Pêche MISE EN GARDE Please

En vigueur depuis le: PAYS Taiwan 20/08/2021 00419 SECTION Produits de la pêche Date de publication 28/07/2007 Liste en vigueur Numéro Nom Ville Régions Activités Remarque Date de la demande d'agrément 2F30017 I-Mei Frozen Foods Company Limited Su-Ao Township Yilan County PP 2F30036 Hsien-Pin Frozen Foods Company Limited Su-Ao Township Yilan County PP Aq 2F30039 Hochico Marine Processing Corporation Su-Ao Township Yilan County PP 2FH0002 Land Young Foods Company Limited Wujie Township Yilan County PP 2FH0005 Jin Tzer Marine Products Company Limited Wujie Township Yilan County PP 2FH0009 JYY Fisheries Corp. Su'ao Yilan County PP 07/01/2011 2FH0013 Tong Ho Foods Industrial Company Limited Wu-Chei Hsiang Ilan Hsien PP 16/05/2011 6F3F001 Peak One International Corporation, Tainan Plant Guanmiau District Tainan City PP 21/01/2011 6F3F003 Shin Rong Business Co., Ltd. Chia-I-Hsien T'ai-wan PP Aq 13/08/2021 6FH0002 Tosei Sea Foods Company Limited Yi-Chu Hsiang, Chia Yi Hsien PP Aq 11/09/2013 6FH0006 Guarantee Liability Yun-Lin County Ko-Fwu Fishes Cooperation Kouhu Township Yunlin County PP Aq 6FH0008 Haw-Di-I Foods Company Limited Sinshih District Tainan City PP 6FH0012 Lian Ruey Enterprise Corporation Limited Annan District Tainan City PP 27/04/2010 7F30035 Tong Pao Frozen Food Company Limited Qiaotou District Kaohsiung City PP 7F30062 Shin Ho Sing Ocean Enterprise Company Limited Qianzhen District Kaohsiung City PP 25/01/2013 1 / 10 Liste en vigueur Numéro Nom Ville Régions Activités Remarque Date de la demande d'agrément 7F30075 Just Champion -

Same Day Flight No

Zip Same Day Flight No. Area Post Office Name Telephone Number Address Code Cut-off time* (03)9324-133 1 Yilan Yilan Jhongshan Rd. Post Office 260 No. 130, Sec. 3, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:30 (03)9326-727 2 Yilan Yilan Jinlioujie Post Office 260 (03)9368-142 No. 100, Sec. 3, Fusing Rd., Yilan 260-51, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 3 Yilan Yilan Weishuei Rd. Post Office 260 (03)9325-072 No. 275, Sec. 2, Jhongshan Rd., Yilan 260-47, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 4 Yilan Yilan Sihou St. Post Office 260 (03)9329-185 No. 2-1, Sihou St., Yilan 260-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 5 Yilan Yilan Donggang Rd. Post Office 260 (03)9385-638 No. 32-30, Donggang Rd., Yilan 260-57, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 6 Yilan Yilan Dapo Rd. Post Office 260 (03)9283-195 No. 225, Sec. 2, Dapo Rd., Yilan 260-54, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 7 Yilan Yilan Shennong Rd. Post Office 260 (03)9356-052 No.1, Sec. 1, Shennong Rd., Yilan City, Yilan County 260-47, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 8 Yilan Yilan County Government Post Office 260 03-9252917 No. 1, Sianjheng N. Rd., Yilan 260-60, Taiwan (R. O. C.) 13:10 (03)9782-628 9 Yilan Toucheng Post Office 261 No. 15, Minfong Rd., Toucheng, Yilan County 261-44, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 10:00 (03)9771-170 10 Yilan Toucheng Dasigang Post Office 261 (03)9781-136 No. -

Non-Anopheline Mosquitoes of Taiwan: Annotated Catalog and Bibliography1

Pacific Insects 4 (3) : 615-649 October 10, 1962 NON-ANOPHELINE MOSQUITOES OF TAIWAN: ANNOTATED CATALOG AND BIBLIOGRAPHY1 By J. C. Lien TAIWAN PROVINCIAL MALARIA RESEARCH INSTITUTE2 INTRODUCTION The studies of the mosquitoes of Taiwan were initiated as early as 1901 or even earlier by several pioneer workers, i. e. K. Kinoshita, J. Hatori, F. V. Theobald, J. Tsuzuki and so on, and have subsequently been carried out by them and many other workers. Most of the workers laid much more emphasis on anopheline than on non-anopheline mosquitoes, because the former had direct bearing on the transmission of the most dreaded disease, malaria, in Taiwan. Owing to their efforts, the taxonomic problems of the Anopheles mos quitoes of Taiwan are now well settled, and their local distribution and some aspects of their habits well understood. However, there still remains much work to be done on the non-anopheline mosquitoes of Taiwan. Nowadays, malaria is being so successfully brought down to near-eradication in Taiwan that public health workers as well as the general pub lic are starting to give their attention to the control of other mosquito-borne diseases such as filariasis and Japanese B encephalitis, and the elimination of mosquito nuisance. Ac cordingly extensive studies of the non-anopheline mosquitoes of Taiwan now become very necessary and important. Morishita and Okada (1955) published a reference catalogue of the local non-anophe line mosquitoes. However the catalog compiled by them in 1955 was based on informa tion obtained before 1945. They listed 34 species, but now it becomes clear that 4 of them are respectively synonyms of 4 species among the remaining 30. -

CRUSTACEAN FAUNA of TAIWAN: BRACHYURAN CRABS, VOLUME I – CARCINOLOGY in TAIWAN and DROMIACEA, RANINOIDA, CYCLODORIPPOIDA Series Editors TIN-YAM CHAN PETER K.L

) ჰ έ ኢ ៉ ̈́ Ҳ ᙂ ඈ ᙷ έ៉ᙂᙷᄫI ᙂ ᄫ ᙷ * I )ჰኢ̈́Ҳඈᙂᙷ* DROMIACEA, RANINOIDA, CYCLODORIPPOIDA DROMIACEA, AND IN TAIWAN CARCINOLOGY I – VOLUME CRABS, BRACHYURAN OF TAIWAN: FAUNA CRUSTACEAN CRUSTACEAN FAUNA OF TAIWAN: BRACHYURAN CRABS, VOLUME I – CARCINOLOGY IN TAIWAN AND DROMIACEA, RANINOIDA, CYCLODORIPPOIDA Series Editors TIN-YAM CHAN PETER K.L. NG SHANE T. AHYONG S. H. TAN S.T. AHYONG & S.H. AHYONG TAN S.T. NG, CHAN, P.K.L. T.Y. ઼ ϲ έ ៉ ঔ ߶ GPNċ1009800139 ̂ ̍ώċ458̮ ጯ ઼ϲέ៉ঔ߶̂ጯ National Taiwan Ocean University 台灣蟹類誌 I (緒論及低等蟹類) CRUSTACEAN FAUNA OF TAIWAN: BRACHYURAN CRABS, VOLUME I – CARCINOLOGY IN TAIWAN AND DROMIACEA, RANINOIDA, CYCLODORIPPOIDA Series Editors TIN-YAM CHAN Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, 2 Pei Ning Road, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, R.O.C. PETER K.L. NG Tropical Marine Science Institute and Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore, Kent Ridge, Singapore 119260, Republic of Singapore. SHANE T. AHYONG Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand. S. H. TAN Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 2, Kent Ridge, Singapore 119260, Republic of Singapore. 國立台灣海洋大學 National Taiwan Ocean University Keelung 2009年1月 [Funded by National Science Council, R.O.C. (NSC96-2621-B-019-008-MY2)] 序 真正的螃蟹屬於甲殼十足目中的短尾類,是大型甲殼類中多樣性 最高的一群,全世界約有6,800多種,自高山、陸地至深海皆有分佈。 台灣的蟹類自1902年起便有積極的調查研究,為大型甲殼類中較受關 注的類群,到目前已記錄有600多種,佔全世界蟹類約十分之一,可見 台灣有很豐富的海洋生物多樣性。本誌是由行政院國家科學委員會補 -

Taiwan Exhibition and Convention Association

Incentive Tours in Taiwan www.taiwan.net.tw Incentive Tours Contents 04 > Discover Taiwan 05 > Transportation in 07 > Time for Nature Taiwan 09 > Time to Marvel 11 > Time to Eat 13 > Time for Two Wheels 15 > Time to Shop 17 > Muslim Friendly Environment in Taiwan 27 > Cruise Travel in Taiwan 29 > 5 Day/ 4 Night Sample Taiwan Incentive Itinerary 31 > 6 Day/ 5 Night Sample Taiwan Incentive Itinerary 34 > Meeting&Event Venues 35 > Special Venues for Every Occasion 39 > Multi-Function Venues 43 > Convention & Exhibition Association 44 > Hotel Meeting Facilities 53 > Government Support 56 > FAQ 01 02 Discover Taiwan A geological marvel, our island, set at ocean's edge, boasts an ancient culture, where the best of human endeavor has been stored up and lives on today. For visitors, this means an amazing concentration of old and new to be experienced through activities that cover every taste and temperament. From Buddhist rituals to high-tech wonders, and lakeside retreats to thrilling mountaineering, Taiwan will stretch the most demanding imagination. Our culture of welcome has come down through 5,000 years of tradition, and you'll find that it still comes from the heart. 03 04 Incentive Tours in Taiwan Transportations Taiwan Getting around Taiwan KEELUNG Easy Access TAIPEI By Domestic Flights Taiwan’s domestic air network provides flights to link 17 airports, serving major centres like Taichung,Tainan,Hualien and TAOYUAN By Air Taitung, as well as off-island territories such as Kinmen, Matsu, Penghu, Green Island and Orchid Island. HSINCHU Taiwan has five main international airports YILAN with international scheduled flights: Taiwan MIAOLI Taoyuan International Airport, Kaohsiung International Airport, Taipei Songshan Airport, By Train Taichung Airport and Tainan Airport.