Retrospetiva Želimir Žilnik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Theory of Political Art: Cultural Politics of 'Black Wave'

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Agora-rakennuksen Alfa-salissa joulukuun 13. päivänä 2014 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in building Agora, Alfa hall, on December 13, 2014 at 12 o’clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2014 Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2014 Editors Jussi Kotkavirta Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Ville Korkiakangas Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:978-951-39-5980-7 ISBN 978-951-39-5980-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-5979-1 (nid.) ISSN 0075-4625 Copyright © 2014, by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2014 ABSTRACT Boynik, Sezgin Towards a Theory of Political Art: Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2014, 87 p. (Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research ISSN 0075-4625; 511) ISBN 978-951-39-5979-1 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-39-5980-7 (PDF) The point of departure of my thesis is to discuss the forms of ’Black Wave’ films made in Yugoslavia during sixties and seventies in relation to political contradictions of socialist self-management. -

Go East by Southeast – 13Th Festival of Central and Eastern European

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org NECSUS Published by: Amsterdam University Press Festival Reviews edited by Marijke de Valck and Skadi Loist of the Film Festival Research Network Go east by southeast 13th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden Greg de Cuir, Jr The Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden,1 also known as ‘goEast’, is a key event on the German film festival calendar. This is perhaps in no small part due to the fact that the festival is organised by the Deutsches Filminstitut, also because it enjoys a dedicated following among enthusiasts of the larger, general festival community. GoEast is structured by a modestly-sized feature film competition section which also includes documentaries. The total number of titles in this section in 2013 was 17. There are a number of smaller special programs at the festival, including a retrospective homage to a master cineaste and a multi-part symposium. The symposium format serves as an example of the profitability of the sites of convergence between film festivals and the academic sphere. Many academics have long been involved with curating and programming activities at festivals; this interaction will likely increase with the further development of the burgeoning field of film festival studies – indeed film festivals themselves may be actively driving this development. The goEast symposium functions as a hybrid academic conference/screening series with a slate of lectures and related film projections. The 2013 symposium was titled Bright Black Frames: New Yugoslav Film Between Subversion and Critique, led by Dr. Gal Kirn (Postdoctoral Fellow, Humboldt Uni- versity Berlin) and Vedrana Madžar (Curator/Filmmaker). -

A Cinematic Battle: Three Yugoslav War Films from the 1960S

A Cinematic Battle: Three Yugoslav War Films from the 1960s By Dragan Batanĉev Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Thesis Supervisor: Professor Balázs Trencsényi Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2012 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The content of my thesis will present the analysis of three Yugoslav war films from the 1960s that they offer different views on World War II as a moment of creation of the state that aimed towards supranationalism and classlessness. I will analyse the films in terms of their production, iconography and reception as to show that although the Yugoslav government, led by a great cinephile Josip Broz Tito, demonstrated interest in the war film genre, there were opposing filmmakers‟ views on what WWII should represent in the Yugoslav history and collective mythology. By using the concept of historiophoty I will demonstrate that the war films represented the failure of Yugoslav government in integrating different nations into a supranational Yugoslav society in which conflicts between different social agents (the state, workers and peasants) will finally be resolved. -

2017-2018 Calendar

Undergraduate Course Offerings 2017-2018 CALENDAR FALL 2017 Saturday, August 26 Opening day New students arrive Monday, August 28 Returning students arrive Tuesday, September 5 Convocation held in Reisinger, 1:30–3 p.m. Monday, October 16 October study days Tuesday, October 17 Wednesday, November 22 Thanksgiving recess through Sunday, November 26 Friday, December 15 Last day of classes Saturday, December 16 Residence halls close at 10 a.m. SPRING 2018 Sunday, January 14 Students return Saturday, March 10 Spring break through Sunday, March 25 Friday, May 11 Last day of classes Sunday, May 13 Residence halls close for first ears,y sophomores, and juniors at 5 p.m. Friday, May 18 Commencement Residence halls close at 8 p.m. The Curriculum . 3 Japanese . 62 Africana Studies . 3 Latin . 63 Anthropology . 3 Latin American and Latino/a Studies . 64 Architecture and Design Studies . 6 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Art History . 6 Studies . 65 Asian Studies . 10 Literature . 67 Biology . 12 Mathematics . 78 Chemistry . 15 Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies . 81 Chinese . 17 Modern and Classical Languages and Classics . 18 Literatures . 81 Cognitive and Brain Science . 19 Music . 82 Computer Science . 19 Philosophy . 93 Dance . 21 Physics . 95 Development Studies . 27 Political Economy . 97 Economics . 27 Politics . 98 Environmental Studies . 29 Psychology . 102 Ethnic and Diasporic Studies . 30 Public Policy . 114 Film History . 31 Religion . 115 Filmmaking and Moving Image Arts . 34 Russian . 118 French . 43 Science and Mathematics . 119 Games, Interactive Art, and New Genres 45 Pre-Health Program Gender and Sexuality Studies . 45 Social Science . 120 Geography . 46 Sociology . -

A Lexicon of Non-Aligned Poetics

Parallel Slalom A Lexicona lexiconof of non-aligned poetics editors Non-aligned Bojana Cvejić Poetics Goran Sergej Pristaš Parallel Slalom A Lexicon of Non-aligned Poetics published by Walking Theory ‒ TkH 4 Kraljevića Marka, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia www.tkh-generator.net and CDU – Centre for Drama Art 6 Gaje Alage, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia www.cdu.hr in collaboration with Academy of Dramatic Art University of Zagreb 5 Trg Maršala Tita, 10000 Zagreb www.adu.hr on behalf of the publisher for walking theory: Ana Vujanović for cdu: Marko Kostanić editors Bojana Cvejić Goran Sergej Pristaš Parallel researchers Jelena Knežević Jasna Žmak coordination Dragana Jovović Slalom translation Žarko Cvejić copyediting and proofreading Žarko Cvejić and William Wheeler A Lexicon of Non-aligned Poetics graphic design and layout Dejan Dragosavac Ruta prepress Katarina Popović printing Akademija, Belgrade print run 400 copies The book was realised as a part of the activities within the project TIMeSCAPES, an editors artistic research and production platform initiated by BADco. (HR), Maska (SI), Bojana Cvejić Walking Theory (RS), Science Communications Research (A), and Film-protufilm Goran Sergej Pristaš (HR), with the support of the Culture programme of the European Union. This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication (communication) reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. with the support of the Culture programme -

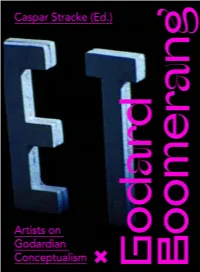

Caspar Stracke (Ed.)

Caspar Stracke (Ed.) GODARD BOOMERANG Godardian Conceptialism and the Moving Image Francois Bucher Chto Delat Lee Ellickson Irmgard Emmelhainz Mike Hoolboom Gareth James Constanze Ruhm David Rych Gabriële Schleijpen Amie Siegel Jason Simon Caspar Stracke Maija Timonen Kari Yli-Annala Florian Zeyfang CONTENT: 1 Caspar Stracke (ed.) Artists on Godardian Conceptualism Caspar Stracke | Introduction 13 precursors Jason Simon | Review 25 Gabriëlle Schleijpen | Cinema Clash Continuum 31 counterparts Gareth James | Not Late. Detained 41 Florian Zeyfang | Dear Aaton 35-8 61 Francois Bucher | I am your Fan 73 succeeding militant cinema Chto Delat | What Does It Mean to Make Films Politically Today? 83 Irmgard Emmelhainz | Militant Cinema: From Internationalism to Neoliberal Sensible Politics 89 David Rych | Militant Fiction 113 jlg affects Mike Hoolboom | The Rule and the Exception 121 Caspar Stracke I Intertitles, Subtitles, Text-images: Godard and Other Godards 129 Nimetöna Nolla | Funky Forest 145 Lee Ellickson | Segue to Seguestration: The Antiphonal Modes that Produce the G.E. 155 contemporaries Amie Siegel | Genealogies 175 Constanze Ruhm | La difficulté d‘une perspective - A Life of Renewal 185 Maija Timonen | Someone To Talk To 195 Kari Yli-Annala | The Death of Porthos 205 biographies 220 previous page: ‘Aceuil livre d’image’ at Hotel Atlanta, Rotterdam, colophon curated by Edwin Carels, IFFR 2019. Photo: Edwin Carels 225 CASPAR STRACKE INTRODUCTION “Pourquoi encore Godard? A question I was asked many times in the course of producing this edited volume. And further: “Wouldn’t this be an appropriate moment in history to pass the torch?” 13 Most likely there is no more torch to pass. -

Poetry, Sculpture and Film On/Of the People's Liberation Struggle

Towards the Partisan Counter-archive: Poetry, Sculpture and Film on/of the People’s Liberation Struggle ❦ Gal Kirn ▶ [email protected] SLAVICA TERGESTINA 17 (2016) ▶ The Yugoslav Partisan Art This essay argues for the construction Эта статья посвящена восстановле- of a Yugoslav Partisan counter-archive нию югославского партизанского capable of countering both the domi- анти-архива с целью дезавуирова- nant narrative of historical revision- ния как доминантного нарратива ism, which increasingly obfuscates исторического ревизионизма, все the Partisan legacy, and the simplistic более игнорирующего партизанское Yugonostalgic narrative of the last наследие, так и упрощенного югоно- few decades. But if we are to engage in стальгического нарратива, возник- rethinking and recuperating the Par- шего после 1991 г. Но если мы хотим tisan legacy we should first delineate переосмыслить и восстановить the specificity and cultural potential партизанское наследство, необходи- of this legacy. This can only be done мо в первую очередь определить его if we grant the Partisan struggle the специфические черты и культурный status of rupture. The essay discusses потенциал. Это возможно только в three artworks from different periods том случае, если мы предоставляем that successfully formalise this rupture партизанскому движению статус in three very diverse forms, namely прорыва. В статье обсуждаются три poetry, sculpture and film. The aim of художественные произведения, соз- these three studies is to contribute to данные в разные периоды, в которых the (counter-)archive of the Yugoslav удалось формализовать этот прорыв Partisan culture. в трёх весьма разных формах, т. е. в поэзии, скульптуре и кино. Изуче- ние этих произведений задумано как вклад в анти-архив югославской партизанской культуры. -

War Trauma and the Terror of Freedom: Yugoslav Black Wave and the Critics of Dictatorship

MISCELLANEA POSTTOTALITARIANA WRATISLAVIENSIA 6/2017 DOI: 10.19195/2353-8546.6.9 SANJA LAZAREVIĆ RADAK* Serbian Academy of Science and Arts (Belgrade, Serbia) War Trauma and the Terror of Freedom: Yugoslav Black Wave and the Critics of Dictatorship War Trauma and the Terror of Freedom: Yugoslav Black Wave and the Critics of Dictatorship. Relying on the concept of cultural trauma, the author interprets the attitude of post-Yugoslav societies towards the so-called Black Wave films. The paper examines the prohibitions of these films during the communist period, the increased interest in them during the 1990s, and finally, its disappearance from popular culture, which all testify the multilayered cultural trauma which Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav societies have been going through since the 1940s. Keywords: cultural trauma, political myth, Black Wave, communism, disintegration of Yugoslavia Травма войны и проблема свободы: югославские фильмы и критика диктатуры. Опираясь на концепцию культурной травмы, автор интерпретирует отношение постюгославских обществ к фильму- нуар. В коммунистическую эпоху Новые фильмы были запрещены; в девяностые годы возник некоторый интерес к «черным фильмам», наконец, они исчезли из популярной культуры. Это свидетельствует о многослойности культурной травмы через которую прошли югославские и постюгославские общества начиная с 1940-х годов до настоящего времени. Ключевые слова: культурная травма, черный фильм, югославские, пост-югославского обще- ства, коммунизм, распад Югославии * Address: Institute for Balkan Studies, Serbian Academy of Science and Arts, Knez-Mihailova 35/4, Belgrade, Serbia. E-mail: [email protected]. Miscellanea Posttotalitariana Wratislaviensia 6/2017 © for this edition by CNS MPW6.indb 107 2017-09-18 12:16:50 108 SANJA LAZAREVIĆ RADAK Historical and Theoretical Framework This paper explores the relationship between collective trauma as public nar- rative and its impact on the reception of the film as a product of popular culture. -

Spring 2014 Film Calendar

Film Spring 2014 Film Spring 2014 National Gallery of Art with American University School of Communication Introduction 5 Schedule 7 Special Events 11 Artists, Amateurs, Alternative Spaces: Experimental Cinema in Eastern Europe, 1960 – 1990 15 Independent of Reality: Films of Jan Němec 21 Hard Thawing: Experimental Film and Video from Finland 23 Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema 27 On the Street 33 Index 36 Divjad (City Scene/Country Scene) p18 Cover: A Short Film about Killing p29 Celebrating the rich and bold heritage of Czech, Finnish, and Polish cinema this season, the National Gallery of Art presents four film series in collaboration with international curators, historians, and archives. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Artists, Amateurs, Alternative Spaces: Experi- mental Cinema in Eastern Europe, 1960 – 1990 gathers more than sixty rarely screened films that reflect nonconformist sensibilities active in former USSR-occupied states. Inde- pendent of Reality: Films of Jan Němec is the first complete retrospective in the United States of the Czech director’s fea- ture films, assembled by independent curator Irena Kovarova, and presented jointly with the American Film Institute (AFI). Hard Thawing — Experimental Film and Video from Finland is a two-part event presenting a view of Finnish artistic practice seldom seen in North America. Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema, a retrospective of the modern cinema of Poland from 1956 through 1989, brings together twenty-one films selected by Scorsese, shown in collabora- tion with Di-Factory and Milestone Film and presented jointly by the Gallery and the AFI. Other screening events include a ciné-concert with Alloy Orchestra, two screenings of Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Flute shown in conjunction with the Washington National Opera’s production of Mozart’s opera, and artist Bill Morrison’s latest work, The Great Flood. -

The Cold War Seen Through the Prism of Yugoslavian Cinema: a ‘Non-Aligned’ View on the Conflict

UDK: 327.54:791(497.1)]:32.019.5 DOI: Original Scientific Paper THE COLD WAR SEEN THROUGH THE PRISM OF YUGOSLAVIAN CINEMA: A ‘NON-ALIGNED’ VIEW ON THE CONFLICT Antoanela Petkovska, PhD Full Professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Skopje, [email protected] Marija Dimitrovska, MA Demonstrator at the Faculty of Philosophy in Skopje [email protected] Abstract: The focus of this paper is the treatment of the topics related to the Cold War in Yugoslavian cinema, compared to the most prominent features of the discourse of the Cold War in Hollywood and the Soviet cinema. The Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, in its four and a half decades of existence, put a significant emphasis on spreading political messages through state-sponsored, mostly feature films. The aspect of the treatment of the Cold War by Yugoslavian cinematography is furthermore intriguing having in mind the unique strategic position the country had in the period of the Cold War, after the deterioration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union’s relations, and the role Josip Broz Tito played in the establishment of the Non-Alignment Movement, which acted buffer zone in the ever growing hostility between the USA and the Soviet Union. The sample of movies we analyze present in a narrative form the perception of the Otherness of both the main protagonists in the conflict and the position of the ‘non-aligned’ view on the Cold War events. The analysis of the political messages in Yugoslavian cinema is all the more compelling having in mind that Yugoslavian officials saw cinema as a very convenient way of sending political messages to the masses through the medium dubbed as Biblia pauperum. -

V 9.72 APRIL 14–21 2014

EXPERIM ENTS IN CINEMA A BASEMENT FILMS PRESENTATION v 9.72 APRIL 14–21 2014 GOING COMMANDO SINCE 2005 NEW MEXICO ARTS TRUST FOR MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING ABQ COMMUNITY FOUNDATION McCUNE CHARITABLE FOUNDATION PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR EXPER- In 2009, St. Andrews Film Studies Publishing House began producing a series of texts about lm festivals. Titles include Film Festivals and Imagined Communities, Archival Film Festivals and, my favorite of the series, Film Festival Yearbook 4: Film Festivals and Activism. In this particular edition, Amalia Cordova contributed the essay “Towards an Indigenous Film Festival Circuit.” Cordova quotes Juan Francisco Salazar from his doctoral thesis titled IMENTS “Imperfect Media: e Poetics of Indigenous Media in Chile.” Salazar’s idea of the “poetics of an imperfect media” is one of those phrases that I just can’t shake. From William S. Burroughs (language is a virus) to Michael Haneke (Hollywood spends too much of its time crossing t’s and dotting i’s), to Noam Chomsky (the vacuous entrails of IN CINEMA the English language in popular media), I wonder if our hyper-familiarity with the language of all-things-cinematic has eviscerated the relevance of this powerful cultural barometer. en, like a super hero, Juan Francisco Salazar swoops in to save the day. e “poetics of an imperfect media;” the poetry of uncrossed t’s and undotted i’s, the poetry APRIL 14–21 of uncharted ideas—ideas that are a little uncomfortable, a bit unfamiliar and always chal- lenging. -

Go East by Southeast – 13Th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden 2013

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Greg de Cuir Jr Go east by southeast – 13th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden 2013 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15086 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: de Cuir Jr, Greg: Go east by southeast – 13th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 2 (2013), Nr. 1, S. 274–280. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15086. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.5117/NECSUS2013.1.DECU Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org NECSUS Published by: Amsterdam University Press Festival Reviews edited by Marijke de Valck and Skadi Loist of the Film Festival Research Network Go east by southeast 13th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden Greg de Cuir, Jr The Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden,1 also known as ‘goEast’, is a key event on the German film festival calendar. This is perhaps in no small part due to the fact that the festival is organised by the Deutsches Filminstitut, also because it enjoys a dedicated following among enthusiasts of the larger, general festival community.