The Odyssey of Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covid-19 Meets the 2020 Election: the Perfect Storm for Misinformation

Thursday, July 9, 2020 Dhul-Qa’da 18, 1441 AH Doha today: 310 - 400 Convergence COVER STORY Covid-19 meets the 2020 election: The perfect storm for misinformation. P4-5 REVIEW BACK PAGE Hanks returns to World War II as a A home away struggling Naval commander. from home. Page 14 Page 16 2 GULF TIMES Thursday, July 9, 2020 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT SERIES TO BINGE WATCH ON AMAZON PRIME PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.20am Shorooq (sunrise) 4.52am Zuhr (noon) 11.40am Asr (afternoon) 3.05pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.29pm Isha (night) 7.59pm USEFUL NUMBERS Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Absentia declared dead. Six years later, she is found in a cabin in the Qatar Airways 44496000 DIRECTION: Matthew Cirulnick, Gaia Violo woods, with no memory of what happened during the time Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 CAST: Stana Katic, Patrick Heusinger, Neil Jackson she went missing. She comes back to a husband who has Qatar General Electricity and SYNOPSIS: She disappeared. No one heard from her for remarried, and whose wife is raising her son. She will have Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 six years. No one knows what happened to her, not even her. to navigate in her new reality, and she will soon fi nd herself Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 An FBI Agent tracking a Boston serial killer vanishes, and is implicated in a new series of murders. 44593363 -

Towards a Theory of Political Art: Cultural Politics of 'Black Wave'

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Agora-rakennuksen Alfa-salissa joulukuun 13. päivänä 2014 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in building Agora, Alfa hall, on December 13, 2014 at 12 o’clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2014 Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH 511 Sezgin Boynik Towards a Theory of Political Art Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2014 Editors Jussi Kotkavirta Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Ville Korkiakangas Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:978-951-39-5980-7 ISBN 978-951-39-5980-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-5979-1 (nid.) ISSN 0075-4625 Copyright © 2014, by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2014 ABSTRACT Boynik, Sezgin Towards a Theory of Political Art: Cultural Politics of ‘Black Wave’ Film in Yugoslavia, 1963-1972 Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2014, 87 p. (Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research ISSN 0075-4625; 511) ISBN 978-951-39-5979-1 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-39-5980-7 (PDF) The point of departure of my thesis is to discuss the forms of ’Black Wave’ films made in Yugoslavia during sixties and seventies in relation to political contradictions of socialist self-management. -

Go East by Southeast – 13Th Festival of Central and Eastern European

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org NECSUS Published by: Amsterdam University Press Festival Reviews edited by Marijke de Valck and Skadi Loist of the Film Festival Research Network Go east by southeast 13th Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden Greg de Cuir, Jr The Festival of Central and Eastern European Film Wiesbaden,1 also known as ‘goEast’, is a key event on the German film festival calendar. This is perhaps in no small part due to the fact that the festival is organised by the Deutsches Filminstitut, also because it enjoys a dedicated following among enthusiasts of the larger, general festival community. GoEast is structured by a modestly-sized feature film competition section which also includes documentaries. The total number of titles in this section in 2013 was 17. There are a number of smaller special programs at the festival, including a retrospective homage to a master cineaste and a multi-part symposium. The symposium format serves as an example of the profitability of the sites of convergence between film festivals and the academic sphere. Many academics have long been involved with curating and programming activities at festivals; this interaction will likely increase with the further development of the burgeoning field of film festival studies – indeed film festivals themselves may be actively driving this development. The goEast symposium functions as a hybrid academic conference/screening series with a slate of lectures and related film projections. The 2013 symposium was titled Bright Black Frames: New Yugoslav Film Between Subversion and Critique, led by Dr. Gal Kirn (Postdoctoral Fellow, Humboldt Uni- versity Berlin) and Vedrana Madžar (Curator/Filmmaker). -

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Saturday, December 8, 2018 Registration Hours: 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM, 4th Floor Exhibit Hall Hours: 9:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 3rd Floor Audio-Visual Practice Room: 7:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 4th Floor, office beside Registration Desk Cyber Cafe - Third Floor Atrium Lounge, 3 – Open Area Session 9 – Saturday – 8:00-9:45 am Slovak Studies Association - (Meeting) - Rhode Island, 5 9-01 Genocide, Identity, and the Nation in the Nazi-Occupied Soviet Territories - Arlington, 3 Chair: Mark Roseman, Indiana U Bloomington Papers: Maris Rowe-McCulloch, U of Toronto (Canada) "August 1942—A Most Violent Month: Violence of Occupation and the Holocaust in German- Controlled Rostov-on-Don, Russia" Trevor Erlacher, UNC at Chapel Hill "Caste, Race, and the Nazi-Soviet War for Ukraine: Dmytro Dontsov at the Reinhard Heydrich Institute" Gelinada Grinchenko, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National U (Ukraine) "How They were Performed: The ‘Dramaturgy’ of Trials of World War II Crimes in the Ukrainian SSR" Disc.: Mark Roseman, Indiana U Bloomington 9-02 Imagined Geographies II: Steppe and Forest: The Historical Dialectic Between Two Ecological Zones - (Roundtable) - Berkeley, 3 Chair: Christine Bichsel, U of Fribourg (Switzerland) Part.: Stephen Brain, Mississippi State U Christopher David Ely, Florida Atlantic U Ekaterina Filep, U of Fribourg (Switzerland) Michael Khodarkovsky, Loyola U Chicago Mikhail Yu. Nemtsev, Independent Scholar 9-03 Laughing Our Way through Soviet History - (Roundtable) - Boston University, 3 Chair: Mayhill C. Fowler, Stetson U Part.: Marilyn Campeau, U of Toronto -

Ekrany 56 Ang Cc21.Indd

Socialist Entertainment Publisher Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Czasopisma o Tematyce Audiowizualnej „Ekrany” Wydział Zarządzania i Komunikacji Społecznej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego w Krakowie Publisher ’s Address ul. Prof. St. Łojasiewicza 4, pok. 3.222 30 ‑348 Kraków e ‑mail: [email protected] www.ekrany.org.pl Editorial Team Miłosz Stelmach (Editor‑in‑Chief) Maciej Peplinski (Guest Editor) Barbara Szczekała (Deputy Editor‑in‑Chief) Michał Lesiak (Editorial Secretary) Marta Stańczyk Kamil Kalbarczyk Academic Board prof. dr hab. Alicja Helman, prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Lubelski, prof. dr hab. Grażyna Stachówna, prof. dr hab. Tadeusz Szczepański, prof. dr hab. Eugeniusz Wilk, prof. dr hab. Andrzej Gwóźdź, prof. dr hab. Andrzej Pitrus, prof. dr hab. Krzysztof Loska, prof. dr hab. Małgorzata Radkiewicz, dr hab. Jacek Ostaszewski, prof. UJ, dr hab. Rafał Syska, prof. UJ, dr hab. Łucja Demby, prof. UJ, dr hab. Joanna Wojnicka, prof. UJ, dr hab. Anna Nacher, prof. UJ Graphic design Katarzyna Konior www.bluemango.pl Typesetting Piotr Kołodziej Proofreading Biuro Tłumaczeń PWN Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Leibniz‑Instituts für Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Europa e. V. in Leipzig. Diese Maßnahme wird mitfinanziert durch Steuermittel auf der Grundlage des vom Sächsischen Landtag beschlossenen Haushaltes. Front page image: Pat & Mat, courtesy of Tomáš Eiselt at Patmat Ltd. 4/2020 Table of Contents Reframing Socialist 4 The Cinema We No Longer Feel Ashamed of Cinema | Ewa Mazierska 11 Paradoxes of Popularity | Balázs Varga 18 Socialist -

A Cinematic Battle: Three Yugoslav War Films from the 1960S

A Cinematic Battle: Three Yugoslav War Films from the 1960s By Dragan Batanĉev Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Thesis Supervisor: Professor Balázs Trencsényi Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2012 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The content of my thesis will present the analysis of three Yugoslav war films from the 1960s that they offer different views on World War II as a moment of creation of the state that aimed towards supranationalism and classlessness. I will analyse the films in terms of their production, iconography and reception as to show that although the Yugoslav government, led by a great cinephile Josip Broz Tito, demonstrated interest in the war film genre, there were opposing filmmakers‟ views on what WWII should represent in the Yugoslav history and collective mythology. By using the concept of historiophoty I will demonstrate that the war films represented the failure of Yugoslav government in integrating different nations into a supranational Yugoslav society in which conflicts between different social agents (the state, workers and peasants) will finally be resolved. -

2017-2018 Calendar

Undergraduate Course Offerings 2017-2018 CALENDAR FALL 2017 Saturday, August 26 Opening day New students arrive Monday, August 28 Returning students arrive Tuesday, September 5 Convocation held in Reisinger, 1:30–3 p.m. Monday, October 16 October study days Tuesday, October 17 Wednesday, November 22 Thanksgiving recess through Sunday, November 26 Friday, December 15 Last day of classes Saturday, December 16 Residence halls close at 10 a.m. SPRING 2018 Sunday, January 14 Students return Saturday, March 10 Spring break through Sunday, March 25 Friday, May 11 Last day of classes Sunday, May 13 Residence halls close for first ears,y sophomores, and juniors at 5 p.m. Friday, May 18 Commencement Residence halls close at 8 p.m. The Curriculum . 3 Japanese . 62 Africana Studies . 3 Latin . 63 Anthropology . 3 Latin American and Latino/a Studies . 64 Architecture and Design Studies . 6 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Art History . 6 Studies . 65 Asian Studies . 10 Literature . 67 Biology . 12 Mathematics . 78 Chemistry . 15 Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies . 81 Chinese . 17 Modern and Classical Languages and Classics . 18 Literatures . 81 Cognitive and Brain Science . 19 Music . 82 Computer Science . 19 Philosophy . 93 Dance . 21 Physics . 95 Development Studies . 27 Political Economy . 97 Economics . 27 Politics . 98 Environmental Studies . 29 Psychology . 102 Ethnic and Diasporic Studies . 30 Public Policy . 114 Film History . 31 Religion . 115 Filmmaking and Moving Image Arts . 34 Russian . 118 French . 43 Science and Mathematics . 119 Games, Interactive Art, and New Genres 45 Pre-Health Program Gender and Sexuality Studies . 45 Social Science . 120 Geography . 46 Sociology . -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines.. -

A Lexicon of Non-Aligned Poetics

Parallel Slalom A Lexicona lexiconof of non-aligned poetics editors Non-aligned Bojana Cvejić Poetics Goran Sergej Pristaš Parallel Slalom A Lexicon of Non-aligned Poetics published by Walking Theory ‒ TkH 4 Kraljevića Marka, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia www.tkh-generator.net and CDU – Centre for Drama Art 6 Gaje Alage, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia www.cdu.hr in collaboration with Academy of Dramatic Art University of Zagreb 5 Trg Maršala Tita, 10000 Zagreb www.adu.hr on behalf of the publisher for walking theory: Ana Vujanović for cdu: Marko Kostanić editors Bojana Cvejić Goran Sergej Pristaš Parallel researchers Jelena Knežević Jasna Žmak coordination Dragana Jovović Slalom translation Žarko Cvejić copyediting and proofreading Žarko Cvejić and William Wheeler A Lexicon of Non-aligned Poetics graphic design and layout Dejan Dragosavac Ruta prepress Katarina Popović printing Akademija, Belgrade print run 400 copies The book was realised as a part of the activities within the project TIMeSCAPES, an editors artistic research and production platform initiated by BADco. (HR), Maska (SI), Bojana Cvejić Walking Theory (RS), Science Communications Research (A), and Film-protufilm Goran Sergej Pristaš (HR), with the support of the Culture programme of the European Union. This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication (communication) reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. with the support of the Culture programme -

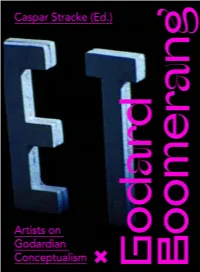

Caspar Stracke (Ed.)

Caspar Stracke (Ed.) GODARD BOOMERANG Godardian Conceptialism and the Moving Image Francois Bucher Chto Delat Lee Ellickson Irmgard Emmelhainz Mike Hoolboom Gareth James Constanze Ruhm David Rych Gabriële Schleijpen Amie Siegel Jason Simon Caspar Stracke Maija Timonen Kari Yli-Annala Florian Zeyfang CONTENT: 1 Caspar Stracke (ed.) Artists on Godardian Conceptualism Caspar Stracke | Introduction 13 precursors Jason Simon | Review 25 Gabriëlle Schleijpen | Cinema Clash Continuum 31 counterparts Gareth James | Not Late. Detained 41 Florian Zeyfang | Dear Aaton 35-8 61 Francois Bucher | I am your Fan 73 succeeding militant cinema Chto Delat | What Does It Mean to Make Films Politically Today? 83 Irmgard Emmelhainz | Militant Cinema: From Internationalism to Neoliberal Sensible Politics 89 David Rych | Militant Fiction 113 jlg affects Mike Hoolboom | The Rule and the Exception 121 Caspar Stracke I Intertitles, Subtitles, Text-images: Godard and Other Godards 129 Nimetöna Nolla | Funky Forest 145 Lee Ellickson | Segue to Seguestration: The Antiphonal Modes that Produce the G.E. 155 contemporaries Amie Siegel | Genealogies 175 Constanze Ruhm | La difficulté d‘une perspective - A Life of Renewal 185 Maija Timonen | Someone To Talk To 195 Kari Yli-Annala | The Death of Porthos 205 biographies 220 previous page: ‘Aceuil livre d’image’ at Hotel Atlanta, Rotterdam, colophon curated by Edwin Carels, IFFR 2019. Photo: Edwin Carels 225 CASPAR STRACKE INTRODUCTION “Pourquoi encore Godard? A question I was asked many times in the course of producing this edited volume. And further: “Wouldn’t this be an appropriate moment in history to pass the torch?” 13 Most likely there is no more torch to pass. -

Sound Mixing for a Comedy Or Drama Series (One Hour)

2018 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Sound Mixing For A Comedy Or Drama Series (One Hour) Altered Carbon Out Of The Past February 02, 2018 Waking up in a new body 250 years after his death, Takeshi Kovacs discovers he's been resurrected to help a titan of industry solve his own murder. The Americans Harvest May 09, 2018 Philip and Elizabeth come together for a perilous operation unlike any they’ve ever had before. Stan and Henry spend a little quality time together. Berlin Station Everything’s Gonna Be Alt-Right October 15, 2017 Under the direction of new Chief of Staff BB Yates (Ashley Judd), Daniel Miller (Richard Armitage), Robert Kirsch (Leland Orser), Valerie Edwards (Michelle Forbes) and the rest of Berlin Station embark on an unsanctioned operation to uncover a possible Far Right terrorist attack. Billions Elmsley Count May 31, 2018 Axe dominates a capital raise event, but is soon challenged by an unexpected competitor. Chuck looks to strike the ultimate blow on an enemy. Wendy reckons with past decisions, and chooses a side. Connerty confronts Sacker about Chuck's activities. Taylor takes a big position. Black Lightning The Resurrection And The Light : The Book Of Pain April 10, 2018 Tobias returns to Freeland and is tasked to capture Black Lightning; after a battle of epic proportions, Anissa and Jennifer provide surprising aid. The Chi Today Was A Good Day February 11, 2018 A neighborhood block party brings Brandon, Ronnie, Emmett and Kevin together. Brandon has a confrontation with Ronnie and is surprised when Jerrika brings another man. -

Poetry, Sculpture and Film On/Of the People's Liberation Struggle

Towards the Partisan Counter-archive: Poetry, Sculpture and Film on/of the People’s Liberation Struggle ❦ Gal Kirn ▶ [email protected] SLAVICA TERGESTINA 17 (2016) ▶ The Yugoslav Partisan Art This essay argues for the construction Эта статья посвящена восстановле- of a Yugoslav Partisan counter-archive нию югославского партизанского capable of countering both the domi- анти-архива с целью дезавуирова- nant narrative of historical revision- ния как доминантного нарратива ism, which increasingly obfuscates исторического ревизионизма, все the Partisan legacy, and the simplistic более игнорирующего партизанское Yugonostalgic narrative of the last наследие, так и упрощенного югоно- few decades. But if we are to engage in стальгического нарратива, возник- rethinking and recuperating the Par- шего после 1991 г. Но если мы хотим tisan legacy we should first delineate переосмыслить и восстановить the specificity and cultural potential партизанское наследство, необходи- of this legacy. This can only be done мо в первую очередь определить его if we grant the Partisan struggle the специфические черты и культурный status of rupture. The essay discusses потенциал. Это возможно только в three artworks from different periods том случае, если мы предоставляем that successfully formalise this rupture партизанскому движению статус in three very diverse forms, namely прорыва. В статье обсуждаются три poetry, sculpture and film. The aim of художественные произведения, соз- these three studies is to contribute to данные в разные периоды, в которых the (counter-)archive of the Yugoslav удалось формализовать этот прорыв Partisan culture. в трёх весьма разных формах, т. е. в поэзии, скульптуре и кино. Изуче- ние этих произведений задумано как вклад в анти-архив югославской партизанской культуры.