Socialisation of Fishing Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kansas Fishing Regulations Summary

2 Kansas Fishing 0 Regulations 0 5 Summary The new Community Fisheries Assistance Program (CFAP) promises to increase opportunities for anglers to fish close to home. For detailed information, see Page 16. PURCHASE FISHING LICENSES AND VIEW WEEKLY FISHING REPORTS ONLINE AT THE DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND PARKS' WEBSITE, WWW.KDWP.STATE.KS.US TABLE OF CONTENTS Wildlife and Parks Offices, e-mail . Zebra Mussel, White Perch Alerts . State Record Fish . Lawful Fishing . Reservoirs, Lakes, and River Access . Are Fish Safe To Eat? . Definitions . Fish Identification . Urban Fishing, Trout, Fishing Clinics . License Information and Fees . Special Event Permits, Boats . FISH Access . Length and Creel Limits . Community Fisheries Assistance . Becoming An Outdoors-Woman (BOW) . Common Concerns, Missouri River Rules . Master Angler Award . State Park Fees . WILDLIFE & PARKS OFFICES KANSAS WILDLIFE & Maps and area brochures are available through offices listed on this page and from the PARKS COMMISSION department website, www.kdwp.state.ks.us. As a cabinet-level agency, the Kansas Office of the Secretary AREA & STATE PARK OFFICES Department of Wildlife and Parks is adminis- 1020 S Kansas Ave., Rm 200 tered by a secretary of Wildlife and Parks Topeka, KS 66612-1327.....(785) 296-2281 Cedar Bluff SP....................(785) 726-3212 and is advised by a seven-member Wildlife Cheney SP .........................(316) 542-3664 and Parks Commission. All positions are Pratt Operations Office Cheyenne Bottoms WA ......(620) 793-7730 appointed by the governor with the commis- 512 SE 25th Ave. Clinton SP ..........................(785) 842-8562 sioners serving staggered four-year terms. Pratt, KS 67124-8174 ........(620) 672-5911 Council Grove WA..............(620) 767-5900 Serving as a regulatory body for the depart- Crawford SP .......................(620) 362-3671 ment, the commission is a non-partisan Region 1 Office Cross Timbers SP ..............(620) 637-2213 board, made up of no more than four mem- 1426 Hwy 183 Alt., P.O. -

POND FISH and FISHING in ILLINOIS by A.C

POND FISH AND FISHING IN ILLINOIS by A.C. LOPI NOT CHIEF FISHERY BIOLOGIST Fishery Bulletin Number 5 Illinois Department of Conservation Division of Fisheries Springfield, Illinois 62706 1967 Page Acknowledgements 2 Introduction .......................................................................................5 THE POND ITSELF 7 The Water . 9 The Food Chain 10 FISH FOR THE FISHING POND 11 Largemouth bass 11 Bluegill 13 Redear sunfish 15 Channel catfish 16 FISH THAT CAN RUIN FISHING 17 Crappie .....................................................17 Bullheads ................................................................................18 Carp — Buffalo — Suckers 18 Green sunfish ...........................................................19 Other fish ............................................................................ 19 STOCKING THE POND ......................................................20 WHEN AND HOW TO FISH THE POND 22 CATCHING FISH 24 Largemouth bass 24 Bluegill ........................................................................... 25 Redear sunfish 25 Channel catfish 25 MANAGING THE POND 28 Aquatic Weed Control .............................................................29 Harvesting and Controlling Bluegills 31 Destroying Spawning Beds 33 Water Level Fluctuations 33 Brush Removal ........................................33 Fertilization ......................................................................... 33 CONTENTS Testing a Pond's Fish Population 34 How to Determine the Condition of a Fish Population -

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines 著者 KAWAMURA Gunzo, BAGARINAO Teodora journal or 鹿児島大学水産学部紀要=Memoirs of Faculty of publication title Fisheries Kagoshima University volume 29 page range 81-121 別言語のタイトル フィリピン, パナイ島の漁具漁法 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/13182 Mem. Fac. Fish., Kagoshima Univ. Vol.29 pp. 81-121 (1980) Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines*1 Gunzo Kawamura*2 and Teodora Bagarinao*3 Abstract The authors surveyed the fishing methods and gears in Panay and smaller neighboring islands in the Philippines in September-December 1979 and in March-May 1980. This paper is a report on the fishing methods and gears used in these islands, with special focus on the traditional and primitive ones. The term "fishing" is commonly used to mean the capture of many aquatic animals — fishes, crustaceans, mollusks, coelenterates, echinoderms, sponges, and even birds and mammals. Moreover, the harvesting of algae underwater or from the intertidal zone is often an important job for the fishermen. Fishing method is the manner by which the aquatic organisms are captured or collected; fishing gear is the implement developed for the purpose. Oftentimes, the gear alone is not sufficient and auxiliary instruments have to be used to realize a method. A fishing method can be applied by means of various gears, just as a fishing gear can sometimes be used in the appli cation of several methods. Commonly, only commercial fishing is covered in fisheries reports. Although traditional and primitive fishing is done on a small scale, it is still very important from the viewpoint of supply of animal protein. -

Fish Traps on Ancient Shores

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2007 Fish traps on ancient shores Eric Stephen White University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation White, Eric Stephen, "Fish traps on ancient shores" (2007). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2197. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/7v2b-4kwu This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISH TRAPS ON ANCIENT SHORES By Eric Stephen White Master of Arts University of Nevada Las Vegas 2007 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1448429 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Guide to the Classification of Fishing Gear in the Philippines

U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services Historic document – Content may not reflect current scientific research, policies or practices. GUIDE TO THE CLASSIFICATION OF FISHING GEAR IN THE PHILIPPINES By AGUSTIN F. UMALI, Ichthyologist Illustrations by Silas G. Duran RESEARCH REPORT 17 Fish and Wildlife Service, Albert M. Day, Director United States Department of the Interior, Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1950 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 40 cents ABSTRACT One of the serious handicaps in the administration and manage ment of the fisheries of the Philippines has been the lack of standardized nomenclature for fishing gear. This publication attempts to solve the problem. It is divided into five parts: The first presents a basic clas sification of fishing gear; the second is a key by means of which fishing gear can be identified and new terms for fishing gear can be properly classified; the third defines and illustrates various types of fishing gear; the fourth is a tabular classification of local Filipino di alect names; and the fifth is a glossary including definitions of more than a thousand terms. CONTENTS Classification of the Gear. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Part I. Basic Classification of Fishing Gear. • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • 6 Part II. Key to the Identification of Classes of Fishing Gear. • . • -

Fishing the Port in January 2019

W.O.C. Fishing the Port of West Sacramento and the D.W.S.C. January Species: Striped Bass, Smallmouth Bass, Largemouth Bass, Sturgeon. General: This is one of the “slow” months as the water is cold and often dirty. Bait fishing (live or dead), throwing lures and jigging will generally do better than trolling. Water temperature/clarity & likely depth(s) fish will be at: 46 to 50-degrees, clear to dirty, 4’ to the bottom. Best time to fish: 60-90 minutes before and after a tide change. Go to http://washingtonoutboardclub.org/ :Tides” 2019 Tide Tables. Best to avoid days or times of the day with ship arrivals or departures. Go to https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ports/20760/USA_port:SACRAMENTO Peak times: First light and dusk. The three-hour period around a tide change. Sections: Trolling Drifting Live Bait Jigging Plugging/Throwing Lures Bait Fishing On-Anchor 1 Trolling When the water is 56-70 degrees, water clear (you can see your prop) to semi-clear (you can see your anti-cavitation plate) & the tides are right (small to medium size). Areas: Rod, reel, main line: 7’ MA rod, 10-17 pound, ¼-3/4 oz; line counter reel with a clicker and 30-pound braid ending with a snap. Leader: 30 inches of 15-25-pound mono with a barrel swivel on one end and a snap on the other. Scents/bait: In off-color water use garlic or shad scent (gel or spray). Lures/colors/speed: 12-16’ water depth: Yo-Zuri Crystal Minnows (center or outside rod, less likely to use it) or Predators (inside rod, less expensive if you lose it). -

Threats from Fishing and Cumulative Impacts

6.2 Adverse impacts of fishing activities under South Atlantic Council Fishery Management Plans (excerpted from Barnette 2001) All fishing has an effect on the marine environment, and therefore the associated habitat. Fishing has been identified as the most widespread human exploitative activity in the marine environment (Jennings and Kaiser 1998), as well as the major anthropogenic threat to demersal fisheries habitat on the continental shelf (Cappo et al. 1998). Fishing impacts range from the extraction of a species which skews community composition and diversity to reduction of habitat complexity through direct physical impacts of fishing gear. The nature and magnitude of the effects of fishing activities depend heavily upon the physical and biological characteristics of a specific area in question. There are strict limitations on the degree to which probable local effects can be inferred from the studies of fishing practices conducted elsewhere (North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries 1999). The extreme variability that occurs within marine habitats confounds the ability to easily evaluate habitat impacts on a regional basis. Obviously, observed impacts at coastal or nearshore sites should not be extrapolated to offshore fishing areas because of the major differences in water depth, sediment type, energy levels, and biological communities (Prena et al. 1999 ). Marine communities that have adapted to highly dynamic environmental conditions (e.g., estuaries) may not be affected as greatly as those communities that are adapted to stable environmental conditions (e.g., deep water communities). While recognizing the pitfalls that are associated with applying the results of gear impact studies from other geographical areas, due to the lack of sufficient and specific information within the Southeast Region it is necessary to review and carefully interpret all available literature in hopes of improving regional knowledge and understanding of fishery-related habitat impacts. -

INSHORE FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES Their Deployment and Use

SPC/Fishenes 24/WP 10 Page 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION TWENTY-FOUR REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia, 3-7 August 1992) INSHORE FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES Their deployment and use. (Paper prepared by the Secretariat) INTRODUCTION 1 Growing regional interest in the development of domestic tuna fisheries has inspired a parallel interest in fish aggregation device (FAD) programme development. The 22nd RTMF reflected this interest in its focus on FADs. At the direction of that meeting the DSFDP has increased its efforts to provide both practical FAD assistance and development work in offshore FAD technology and exploitation. In addition, as directed by the 22nd RTMF, the Project has widened the scope of its activities to include, among other things, an ongoing effort to develop effective technology and exploitation techniques for FADs set in shallow inshore waters, most often for the particular purpose of aggregating baitfish species. 2. Apart from appropriate gear, the single most important ingredient for successful mid- water tuna fishing techniques, such as vertical and horizontal longlining and mid-water handlining, is the availability of suitable bait. It is widely recognised among Pacific island fisherman that small pelagic species such as big-eye scad (Seiar crumenophthalmus) and round scad (Decapterus spp.). which are widely known in the region by variations of the common Polynesian names of atule and opeta respectively, being a natural prey of tuna, make for superior bait. 3 These and some other small pelagic species also provide a seasonal source of food fish in some areas and fisherman have learned a good deal on a localised basis about the seasonal occurrence and behaviour of these, fishes. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 159/Friday, August 16, 2019/Notices

41966 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 159 / Friday, August 16, 2019 / Notices Dated: August 13, 2019. • Instructions: Comments sent by any traps to target lionfish. Because FWC Tracey L. Thompson, other method, to any other address or requested that the amended EFP remove Acting Deputy Director, Office of Sustainable individual, or received after the end of the requirement that research traps have Fisheries, National Marine Fisheries Service. the comment period, may not be a current endorsement, stamp, or [FR Doc. 2019–17626 Filed 8–15–19; 8:45 am] considered by NMFS. All comments certification and allow sampling during BILLING CODE 3510–22–P received are a part of the public record the spiny lobster closed season, the EFP and will generally be posted for public would exempt research traps from the viewing on www.regulations.gov gear identification requirements at 50 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE without change. All personal identifying CFR 622.402(a) and exempt the information (e.g., name, address), activities from the seasonal closures at National Oceanic and Atmospheric confidential business information, or 50 CFR 622.403. The amended EFP Administration otherwise sensitive information would also exempt the project activities RIN 0648–XS004 submitted voluntarily by the sender will from the closed seasons, size limits, and be publicly accessible. NMFS will bag limits at 50 CFR 622.34, 622.37, and Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of accept anonymous comments (enter ‘‘N/ 622.38 to allow FWC to retain other fish Mexico, and South Atlantic; Exempted A’’ in the required fields if you wish to for species identification verification Fishing Permits remain anonymous). -

Chapter 6 Passive Capture Techniques

Chapter 6 Passive Capture Techniques WAYNE A. HUBERT, KEVIN L. POPE, AND JOHN M. DETTMERS 6.1 INTRODUCTION Passive capture techniques involve the capture of fishes or other aquatic animals by en- tanglement, entrapment, or angling devices that are not actively moved by humans or ma- chines while the organisms are being captured (Lagler 1978). The behavior and movements of the animals themselves result in their capture. The techniques used in passive sampling of fish populations are similar to those used for food gathering over the centuries. Nets and traps have been widely used among various cultures, and many of the currently applied techniques were used by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans (Alverson 1963). Based on their mode of capture, passive sampling devices can be divided into three groups: (1) entanglement, (2) entrapment, and (3) angling gears. Entanglement devices capture fish by holding them ensnared or tangled in webbing or mesh made of natural or artificial materials. Gill nets and trammel nets are examples of entanglement gears (Figure 6.1). Entrapment de- vices capture organisms that enter an enclosed area through one or more funnel- or V-shaped openings that hinder escape after entrance. Hoop nets, trap nets, and pot devices are examples of entrapment gears (Figures 6.2 and 6.3). Angling devices capture fish with a baited hook and line. Trotlines and longlines are examples of passive angling gears (Figure 6.4). Gear selectivity and gear efficiency are important considerations with respect to passive sam- pling devices. Often these terms are used interchangeably, but they have different, specific defi- nitions. -

Survey and Impact Assessment of Derelict Fish Traps in St. Thomas and St

Survey and Impact Assessment of Derelict Fish Traps in St. Thomas and St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands Randy Clark Simon J. Pittman Timothy A. Battista Chris Caldow NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science June 2012 NOAA TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NOS NCCOS 147 NOAA NCCOS Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment Acknowledgements Many thanks go to NOAA’s Marine Debris Program for providing the funding for this project. We would like to thank all those who made this project successful, we are grateful for your help and assistance: To all the members of the St. Thomas Fishermen’s Association, and in particular, Julian Magras, Darryl Bryan and Winston Ledee. Lance Horn and Glenn Taylor with NOAA’s Undersea Research Center, and all the crew from the NOAA ship R/V Nancy Foster- thanks for helping us with the derelict fi sh trap verifi cation! Thank you to the great folks at the U.S. Navy’s Naval Surface Warfare Center-Panama City Division, especially Ana Ziegler and Aamir Qaiyumi; and Rafe Boulon and Ken Wilde at the National Park Service, St. John Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument. In addition, we would like to thank L. Bauer, M. Kendall, and A. Uhrin for their constructive comments on the manuscript; and Sarah D. Hile and Jamie Higgins for document production. Contract support was provided by Consolidated Safety Service, Inc. under NOAA Contract No. DG133C07NC0616. The covers for this document were designed and created by Gini Kennedy (NOAA). Cover photos were provided by St. Thomas Fishermen’s Association (far left photo in banner on front cover) and NOAA NCCOS Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment’s Biogeography Branch (all other photos). -

Fishing Methods List

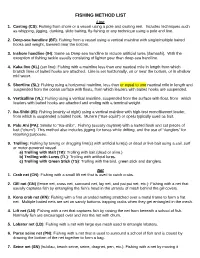

FISHING METHOD LIST Line 1. Casting (CS): Fishing from shore or a vessel using a pole and casting reel. Includes techniques such as whipping, jigging, dunking, slide baiting, fly-fishing or any technique using a pole and line. 2. Deep-sea handline (BF): Fishing from a vessel using a vertical mainline with single/multiple baited hooks and weight, lowered near the bottom. 3. Inshore handline (IH): Same as Deep-sea handline to include artificial lures (damashi). With the exception of fishing tackle usually consisting of lighter gear than deep-sea handline. 4. Kaka line (KL) (set line): Fishing with a mainline less than one nautical mile in length from which branch lines of baited hooks are attached. Line is set horizontally, on or near the bottom, or in shallow mid water. 5. Shortline (SL): Fishing using a horizontal mainline, less than or equal to one nautical mile in length and suspended from the ocean surface with floats, from which leaders with baited hooks are suspended. 6. Verticalline (VL): Fishing using a vertical mainline, suspended from the surface with float, from which leaders with baited hooks are attached and ending with a terminal weight. 7. Ika-Shibi (IS): Fishing (mainly at night) using a vertical mainline with high-test monofilament leader, from which is suspended a baited hook. Muhe’e (“true squid”) or opelu typically used as bait. 8. Palu Ahi (PA): Similar to “Ika-shibi”. Fishing (usually daytime) with a baited hook and cut pieces of bait (“chum”). This method also includes jigging for tunas while drifting, and the use of “danglers” for reporting purposes.