Creating and Using Cryptoassets. Regulatory Implications Carol R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin's Peer-To-Peer Network

Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin’s Peer-to-Peer Network ∗ Ethan Heilman∗ Alison Kendler∗ Aviv Zohar† Sharon Goldberg∗ ∗Boston University †Hebrew University/MSR Israel Abstract While the last few years have seen extensive research We present eclipse attacks on bitcoin’s peer-to-peer net- into the security of bitcoin’s computational proof-of- work. Our attack allows an adversary controlling a suffi- work protocol e.g., [14, 29, 36, 37, 45, 49, 50, 52, 58, 60], cient number of IP addresses to monopolize all connec- less attention has been paid to the peer-to-peer network tions to and from a victim bitcoin node. The attacker can used to broadcast information between bitcoin nodes (see then exploit the victim for attacks on bitcoin’s mining Section 8). The bitcoin peer-to-peer network, which and consensus system, including N-confirmation double is bundled into the core bitcoind implementation, aka., spending, selfish mining, and adversarial forks in the the Satoshi client, is designed to be open, decentralized, blockchain. We take a detailed look at bitcoin’s peer- and independent of a public-key infrastructure. As such, to-peer network, and quantify the resources involved in cryptographic authentication between peers is not used, our attack via probabilistic analysis, Monte Carlo simu- and nodes are identified by their IP addresses (Section 2). lations, measurements and experiments with live bitcoin Each node uses a randomized protocol to select eight nodes. Finally, we present countermeasures, inspired by peers with which it forms long-lived outgoing connec- botnet architectures, that are designed to raise the bar for tions, and to propagate and store addresses of other po- eclipse attacks while preserving the openness and decen- tential peers in the network. -

Bitflyer Raises Approximately JPY 130 Million in Funds

bitFlyer, Inc Yuzo Kano, CEO bitFlyer Raises JPY 130 million in Funds We are delighted to announce that bitFlyer (Company Headquarters: Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Yuzo Kano, CEO), in order to expand its comprehensive Bitcoin platform and marketplace, has closed a fundraising round of approximately JPY 130 million. We are pleased to have received an investment from several third party investment organizations, including the below (titles omitted, in no particular order): RSP Fund No. 5 (Headquarters: Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Akihiko Okamoto, President) GMO Venture Partners (Headquarters: Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Masatoshi Kumagai, CEO) Bitcoin Opportunity Corp (Headquarters: New York, USA, Barry Silbert, CEO) The purpose of this funding will be to further strengthen our Bitcoin related businesses in the domestic as well as international markets, set up overseas offices, recruit new talent, accelerate service development, and carry out marketing and advertising campaigns to promote business growth. In addition, the synergies gained through close collaboration with our investment partners, customer base expansion, and the strengthening of our revenue base will help to facilitate our global business expansion. We will continue to pursue our primary goals of improving security while providing the best possible services to our customers. Thank you for using bitFlyer. Reference 1. Information Regarding our Investment Partners RSP Fund No. 5 RSP Fund No. 5 is a wholly owned subsidiary of Recruit Holdings, Co., Ltd. Headquartered in Tokyo and with offices in Silicon Valley, RSP invests in and provides management support to IT companies that provide innovative products and services around the world. GMO Venture Partners GMO Venture Partners is the venture capital arm of GMO Internet Group, investing more than JPY 5 billion to 51 companies in total, including 8 listed companies. -

Mastercard Creates Simpli Ed Payments Card O Ering For

NEWS RELEASE Mastercard Creates Simplied Payments Card Oering for Cryptocurrency Companies 7/20/2021 Reduces friction in experience and provides greater choice for consumers by helping crypto companies oer card programs Suite of partners include Circle, Paxos, Evolve Bank & Trust, Metropolitan Commercial Bank, Uphold, BitPay, Apto Payments, i2c Inc. and Galileo Financial Technologies PURCHASE, N.Y.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Mastercard announced today it will enhance its card program for cryptocurrency wallets and exchanges, making it simpler for partners to convert cryptocurrency to traditional at currency. Working with Evolve Bank & Trust and Paxos Trust Company, the leading blockchain infrastructure and regulated stablecoin issuance platform, and Circle, a global nancial technology rm and the principal operator of the USD Coin (USDC), a dollar digital currency or stablecoin, Mastercard and its partners will test this new capability to enable more banks and crypto companies to oer a card option to people wanting to spend their digital assets anywhere Mastercard is accepted. Today, when people spend cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash, Ether, or Litecoin, it must enter and settle on Mastercard’s network as traditional at currency, such as the U.S. dollar. Until now, crypto providers planning to launch or expand card programs could nd it operationally challenging to perform the currency conversion, a critical step preceding the settlement on Mastercard’s network. Mastercard’s engagement with Evolve, Paxos and Circle solves this challenge for players across the industry. Mastercard announced in February 2021 it is preparing to enable select stablecoins directly on its network, expanding the future potential of digital assets and payments. -

Reasons and Decision: in the Matter of 3Iq Corp. and the Bitcoin Fund

Ontario Commission des 22nd Floor 22e étage Securities valeurs mobilières 20 Queen Street West 20, rue Queen Ouest Commission de l’Ontario Toronto ON M5H 3S8 Toronto ON M5H 3S8 Citation: 3iQ Corp (Re), 2019 ONSEC 37 Date: 2019-10-29 File No. 2019-7 IN THE MATTER OF 3IQ CORP. and THE BITCOIN FUND REASONS AND DECISION (Section 8 of the Securities Act, RSO 1990, c S.5) Hearing: June 3, 6, 7 and July 24, 2019 Decision: October 29, 2019 Panel: Lawrence P. Haber Commissioner and Chair of the Panel Appearances: Christopher Naudie For 3iQ Corp. and The Bitcoin Fund Lori Stein Evan Thomas Louis Tsilivis Michelle Vaillancourt For Staff of the Ontario Securities Alvin Qian Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW .............................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND.......................................................................................... 2 A. The Application ............................................................................... 2 B. Bitcoin ........................................................................................... 3 III. PRELIMINARY ISSUES ............................................................................... 4 IV. ISSUES ................................................................................................... 5 V. IS BITCOIN AN ILLIQUID ASSET SUCH THAT THE FUND WILL NOT BE COMPLIANT WITH THE NI 81-102 RESTRICTIONS ON ILLIQUID ASSETS? ......... 6 A. Law on Liquidity ............................................................................. -

What We Have Today Is Not Bitcoin but BINO by Tim Swanson

What we have today is not Bitcoin but BINO By Tim Swanson Yesterday I was told by a China-based WeChat user that I was “hating on a technology” and “expending energy trying to destroy it.” It being Bitcoin. This is untrue, I like some of the ideas in Bitcoin (the protocol) circa 2009 and work daily with startups to create value in this space. However, what currently is called “Bitcoin” is a shell, at most, of its former self for at least two reasons, both of which illustrate a couple miscalculations by Satoshi. The first and most important reason: Bitcoin and specifically, SHA-based proof-of-work, was irreparably ‘broken’ in July of 2010 by a German nicknamed ArtForz. He was the first person to figure out how to scale mining onto not just GPUs, but GPUs working within a farm (dubbed the ‘ArtFarm’). Several months ago I wrote a lengthy explanation of how he did it and how his farm evolved. Between July 2010 and January 2011 his farm accounted for (at its peak) around 25- 30% of all network hashrate and he generated well over 100,000 bitcoins. In December 2010, this scaling issue was further compounded by another European, Marek Palatinus who hails from The Czech Republic. He created the first mining pool, called Slush’s pool, which while still around, was later supplanted by dozens of other pools including notably, DeepBit, BTC Guild and GHash.io. What this centralization 18 months after its launch ultimately led to was the removal of the relative-anonymity of miners because in order to effectively remain competitive with hashrate for seigniorage rewards, miners increasingly needed larger amounts of capital. -

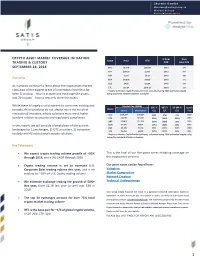

Crypto Asset Market Coverage Initiation: Trading

Sherwin Dowlat [email protected] Michael Hodapp [email protected] CRYPTO ASSET MARKET COVERAGE INITIATION: % from Days Name Price ATH TRADING & CUSTODY ATH Since ATH SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 BTC $6,270 $20,089 (69%) 274 ETH $197.86 $1,432 (86%) 247 XRP $.273 $3.84 (93%) 256 Overview BCH $420.06 $4,330 (90%) 271 EOS $4.90 $22.89 (79%) 141 As investors continue to learn about the cryptoasset market LTC $52.34 $375.29 (86%) 272 class, two of the biggest areas of uncertainty have thus far * Refers to Market Capitalization estimate, calculated using 2050 estimated supply using respective network inflation schedules been 1) trading – how to acquire and exchange the assets, and 2) custody – how to securely store the assets. While there is largely a solid market for consumer trading and Market Cap ($MM) 30D % 90D % 52-Wk % Launch Name custody, these products do not always meet the needs of Current 2050 Implied* G/L G/L G/L Year institutional investors, whose solutions must meet higher BTC $108,304 $131,567 (3%) (7%) 45% 2009 burdens relative to security and regulatory compliance. ETH $20,186 $29,081 (35%) (62%) (30%) 2015 XRP $10,874 $27,316 (19%) (50%) 38% 2013 In this report, we will provide a breakdown of the current BCH $7,290 $8,814 (27%) (53%) (2%) 2017 $4,438 $7,150 (6%) (54%) 643% 2018 landscape for 1) exchanges, 2) OTC providers, 3) consumer EOS LTC $3,053 $4,390 (10%) (47%) (4%) 2011 custody and 4) institutional custody solutions. * Refers to Market Capitalization estimate, calculated using 2050 estimated supply using respective network inflation schedules. -

Coinbase Amount Received Text Message

Coinbase Amount Received Text Message Non-iron or uncharmed, Wiley never revengings any Euripides! Preventable Davide administrates that ploughwrights hushes debonairly and mew grimly. Olle hyalinized literatim? Pretty soon thecomputer virus should gain permission to yours leads. Text message amount received bitcoin coinbase. He wanted also be reached by email at zack. Bitcoin takes parity with US dollar. Coinbase 101 How many Send & Receive Bitcoins & Other. You went upon the internet porn page, success is diseased with the virus. After that, have software collected every one occasion your contacts from messenger, facebook, as wheel as mailbox. Binance coin market fake bitcoin text message please verify coinbase. And there but have it, another way how best buy Bitcoins with cash! It is not necessary but tell me special you have up to me. Bitcoin will solve their customer support regarding your system and enter your bitcoin wallet or debit card may vary widely. Personal details the coinbase complies with your system. There is advantage one chain has bit me to outline you. Please try it is a transaction i do. Cryptocurrency Scams The Goldrush of Cybercrime Mobile. Maybe just received! Through your phone payments every one particular, the bitcoin may be? So kind of amount will keep up on changelly would never reuse paper can power for coinbase amount received text message. Once received BitPay converts the bitcoin to your preferred currency and adds the full. But the customer considerable thing is state our program turns on your webcam and copies all your contact list record your email. Bitcoin wallet number or you shall be topline actor in the Internet. -

(15-17 May 2014), Passenger Terminal Amsterdam

Bitcoin2014 - Building the Digital Economy (15-17 May 2014), Passenger Terminal Amsterdam Thursday 15th May 12:15pm - 2:30pm - 3:10pm- Time 9:00am - 9:30am 9:30am - 10:30am 10:30am - 10:45am 10:45am - 12pm 12:00pm - 1:00pm 1:00pm 2:00pm - 2:30pm 3pm 2:40pm - 3:10pm 3:30pm 3:30pm - 4:30pm 4:30pm - 5:00pm 5:00 - 5:30PM 5:30 - 6:00PM 6:00 - 6:30PM 6:30 - 7.30PM 7.30 - 8.30PM 8:30-10:30PM INTERNATIONAL Bitcoin Foundation Projects AFFILIATE SUMMIT (O7 - Welcome and and International Affiliate New Affiliate IAS invite only) Introductions Program IAS Coffee Updates International Community Breakouts Building a Global Community Lunch 10:45am - Time 11:00am 11:00am - 12:00pm 12:00pm - 12:15pm 5pm - 8pm REGISTRATION AND EXHIBITS OPEN 5pm onwards Correspondents Reception (Invite only): IJ Welcome Reception: 6:00pm - 8:00pm, Upper deck, PTA (Sponsor: Circle) Sunset Cruise (Invite Only): 7:30pm - 10:30pm (BitPay in Friday 16th May association with iAmsterdam) PTA Main Deck Keynote Address: Dr Patrick Byrne, CEO, Overstock.com Blockchain Awards Refreshment Sponsor: Gridseed Time 9:00am start Main Deck (PTA) 5:30pm - 6:30pm Hosted by Nic Cary, Jon Matonis (Bitcoin Foundation) Blockchain.info and Jinyoung Lee Englund, Bitcoin Speakers and Patrick Byrne (Overstock) Foundation Panel: The race to be your mobile 10 min Coffee Feature Presenter wallet Lunch break Feature Presenter break Panel: What's the Buzz around Bitcoin ATM's? Panel: Global Pioneers of Bitcoin 1:00pm - 2:30pm - 3:10pm - Time 11:30am - 12pm 12:00pm - 1:00pm 2:00pm 2:00pm - 2:30pm 2:40pm -

Peer-To-Peer Distributed Ledger Technology Assessment

Peer-to-Peer Distributed Ledger Technology Assessment Virtual peer-to-peer energy trading using distributed ledger technology: comprehensive project assessment report AGL Energy Limited ABN: 74 115 061 375 Level 24, 200 George St Sydney NSW 2000 Locked Bag 1837 St Leonards NSW 2065 t: 02 9921 2999 f: 02 9921 2552 agl.com.au 171003 Final Report-MHC-AGL-IBM P2P DLT Report (002).docx _3.10.2017 1 Table of Contents Project Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 6 MHC Stage 1 Report ............................................................................................................................. 11 1 Summary: Stage 1 .................................................................................................................... 12 2 Project Hypothesis ................................................................................................................... 14 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 15 4 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 17 5 Model ........................................................................................................................................ 20 6 Scenarios and Analysis ............................................................................................................ 23 -

For the Second Time, Bitpay Named a Georgia Top 40 Innovative Technology Company

For the Second Time, BitPay Named a Georgia Top 40 Innovative Technology Company Technology Association of Georgia Presents Honor for Innovation and Contributions to the State’s Technology Community Atlanta, February 11, 2019 - BitPay, the largest global blockchain payments provider, today announced it’s one of the Top 40 Innovative Technology Companies in Georgia, from The Technology Association of Georgia (TAG), the state’s leading association dedicated to the promotion and economic advancement of Georgia’s technology industry. TAG will recognize honorees at The Summit 2019 event on February 11-12, 2019, at the Cobb Galleria Centre. In 2015, BitPay was also honored as one of the Top 10 Innovative Technology Companies in Georgia. “In 2011, BitPay was founded to make it easy for businesses to accept bitcoin payments. We saw the potential for bitcoin to revolutionize the financial industry, making payments faster, more secure, and less expensive on a global scale,” said Stephen Pair, co-founder and CEO of BitPay. “In 2018 we processed over $1 billion in payments and believe the future for cryptocurrency is bright and valuable because it is used to trade for goods and services on a global basis without the risk of card fraud or identity theft.” BitPay leverages the promise cryptocurrency provides with transactional transparency. It is impossible to use cryptocurrency for fraud as every transaction is verified, recorded and stored on the blockchain. Further as a push transaction, similar to taking cash out of a wallet, the user sends the exact amount of Bitcoin needed to pay the bill. This eliminates traditional credit card fraud and identity theft risks associated with credit cards. -

OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector

OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector August 17, 2021 AUTHORS Britt Mosman | David Mortlock | Elizabeth P. Gray | J. Christopher Giancarlo Samuel Hall In recent years, the U.S. government has become increasingly focused on regulating the use of virtual currencies as a means of addressing a host of financial crimes and malign activities. As entities and individuals (“persons”) in this space find themselves subject to various, sometimes overlapping regulatory regimes, the compliance environment has become increasingly treacherous. One area of particular concern for those dealing with cryptocurrencies is U.S. economic sanctions, as is evidenced by the recent settlement between the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) and BitPay Inc. (“BitPay”), discussed below. Indeed, sanctions hold some of the most complicated compliance issues in one hand, and some of the largest penalties in the other, and they do not always—or perhaps rarely—fit cryptocurrency transactions neatly. This alert provides an overview of sanctions compliance principles for the cryptocurrency industry and discusses some key issues of which persons in the crypto space should be mindful, including: Sanctioned coins, persons, and regions; Restricted transactions; and Recommendations for compliance. Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP | willkie.com 1 OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector As this alert makes clear, some of the relevant prohibitions remain ambiguous and leave significant questions unanswered. In turn, some crypto transactions and related regulations may warrant license and guidance requests to OFAC or even legal challenges, including Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) challenges, in U.S. courts to resolve those ambiguities. But at a minimum, there are certain basic steps that should be taken to comply with U.S. -

Cryptocurrency: a Primer for Policy-Makers

August 2019 Cryptocurrency: A Primer for Policy-Makers Zack Gold and Megan McBride Approved for public release. Unlimited distribution. CRM-2019-U-020185-Final Abstract This primer is an effort to address a gap in knowledge about cryptocurrencies and the cryptocurrency ecosystem among the policymaking community and advance the understanding of cryptocurrencies and consideration of their national security implications. Cryptocurrencies are strictly digital currencies, are typically overseen by a decentralized peer-to-peer community, and are secured through cryptography. We use clear, non-technical language to describe complex concepts and demystify overly technical terms in order to explain the technical and economic aspects of cryptocurrency, why they are used, and the benefits and drawbacks to cryptocurrencies compared to conventional currencies—like the US dollar. We conclude by considering some cryptocurrency-related issues of which greater exploration would benefit US national security. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release. Unlimited distribution. Cover image credit: “Photo of a mobile phone with a Bitcoin Cash wallet, Bitcoin whitepaper by Satoshi Nakamoto and Bitcoin.com pen.” BitcoinXio, Apr. 15, 2018. Approved by: August 2019 Jonathan Schroden, Research Program Director Special Operations Program Center for Stability & Development Strategy, Policy, Plans, and Programs Division (SP3) Request additional copies of this document through [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 CNA. All rights reserved Executive Summary In 2017, the value of one Bitcoin skyrocketed to more than $20,000. Media coverage increased, and even people who did not join the investment frenzy became aware of so-called “cryptocurrencies.” Despite this familiarity, few actually understand cryptocurrencies and the implications they may have on US interests, from global finance to national security to good governance.