The End of the Cold War: 30 Years on 427

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documents of Contemporary Art: TIME Edited by Amelia Groom, the Introduction Gives an Overview of Selected Writings Addressing Time in Relation to Art

“It is important to realize that the appointment that is in question in contemporariness does not simply take place in chronological time; it is something that, working within chronological time, urges, presses and transforms it. And this urgency is the untimeliness, the anachronism that permits us to grasp our time in the form of a ‘too soon’ that is also a ‘too late’; of an ‘already’ that is also a ‘not yet.’ Moreover, it allows us to recognize in the obscurity of the present the light that, without ever being able to reach us, is perpetually voyaging towards us.” - Giorgio Agamben 2009 What is the Contemporary? FORWARD ELAINE THAP Time is of the essence. Actions speak louder than words. The throughline of the following artists is that they all have an immediacy and desire to express and challenge the flaws of the Present. In 2008, all over the world were uprisings that questions government and Capitalist infrastructure. Milan Kohout attempted to sell nooses for homeowners and buyers in front of the Bank of America headquarters in Boston. Ernesto Pujol collaborated and socially choreographed artists in Tel Aviv protesting the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Indonesian artist, Arahmaiani toured the world to share “HIS Story,” performances creating problematic imagery ending to ultimately writing on her body to shine a spotlight on the effects of patriarchy and the submission of women. All of these artists confront terrorism from all parts of the world and choose live action to reproduce memory and healing. Social responsibility is to understand an action, account for the reaction, and to place oneself in the bigger picture. -

Číslo Ke Stažení V

Knihovna města Petřvald Foto Monika Molinková 4 MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY Cena 40 Kč * * OBSAH MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY 4 2015 ročník 67 FROM THE CONTENTS 123 ..... * TOPIC: National Digital Library – under the lid Luděk Tichý |123 * INTERVIEW with Vlastimil Vondruška, Czech writer and historian: 1 Pod pokličkou Národní digitální knihovny Vydává: “Books are written to please the readers, not the critics…” * Luděk Tichý Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková |125 příspěvková organizace Středočeského kraje, ..... * Klára’s cookbook or Ten recipes for library workshops: 125 ul. Generála Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno „Knihy se nepíšou proto, aby se líbily literárním Non-fiction in museum sauce Klára Smolíková |129 * REVIEW: How philosopher Horáček came to Paseka publishers kritikům, ale čtenářům…“ Evid. č. časopisu MK ČR E 485 and what came of it Petr Nagy |131 * Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková ISSN 0011-2321 (Print) ISSN 1805-4064 (Online) * INTERVIEW with PhDr. Dana Kalinová, World of Books Director: Šéfredaktorka: Mgr. Lenka Šimková Choosing from the range will be difficult again… Olga Vašková |133 ..... 129 Redaktorka: Bc. Zuzana Mračková * The future of public libraries in the Czech Republic in terms Grafická úprava a sazba: Kateřina Bobková of changes to the pensions system and social dialogue Poučné knížky v muzejní omáčce * Klára Smolíková Renáta Salátová |135 Sídlo redakce (příjem inzerce a objednávky na předplatné): * FROM ABROAD: The road to Latvia or Observations 131 ..... Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, from the Di-Xl conference Petr Schink |138 Kterak filozof Horáček k nakladatelství Paseka příspěvková organizace, Gen. Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno * The world seen very slowly by Jan Drda Naděžda Čížková |142 přišel a co z toho vzešlo * Petr Nagy Tel.: 312 813 154 (Lenka Šimková) * FROM THE TREASURES… of the West Bohemian Museum Library Tel.: 312 813 138 (Bc. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 194

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194 Jessica Giandomenico Transformative Power Challenged EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Brusewitzsalen, Gamla Torget 6, Uppsala, Saturday, 19 December 2015 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor David Phinnemore. Abstract Giandomenico, J. 2015. Transformative Power Challenged. EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited. Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194. 237 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-9403-2. The EU is assumed to have a strong top-down transformative power over the states applying for membership. But despite intensive research on the EU membership conditionality, the transformative power of the EU in itself has been left curiously understudied. This thesis seeks to change that, and suggests a model based on relational power to analyse and understand how the transformative power is seemingly weaker in the Western Balkans than in Central and Eastern Europe. This thesis shows that the transformative power of the EU is not static but changes over time, based on the relationship between the EU and the applicant states, rather than on power resources. This relationship is affected by a number of factors derived from both the EU itself and on factors in the applicant states. As the relationship changes over time, countries and even issues, the transformative power changes with it. The EU is caught in a path dependent like pattern, defined by both previous commitments and the built up foreign policy role as a normative power, and on the nature of the decision making procedures. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

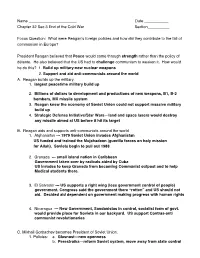

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

U.S.-Russian Relations Potomac Paper 22

PPoottoommaacc PPaappeerr 2222IFRI ______________________________________________________________________ U.S.-Russian relations The path ahead after the crisis __________________________________________________________________ Jeffrey Mankoff December 2014 United States Program The Institut français des relations internationals (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The views expressed herein are those of the authors. The United States Program at Ifri publishes a series of online policy papers called “Potomac papers”. They present analyses of U.S. policies, politics and social debates, and are reviewed by experts before publication. They are written either in English or French, with a one-page executive summary in both languages. Dr. Laurence Nardon, Head of the U.S. Program at Ifri, is the editor. Many thanks are extended to the Russia/NIS Center at Ifri, whose team kindly agreed to review the -

Yeltsin's Winning Campaigns

7 Yeltsin’s Winning Campaigns Down with Privileges and Out of the USSR, 1989–91 The heresthetical maneuver that launched Yeltsin to the apex of power in Russia is a classic representation of Riker’s argument. Yeltsin reformulated Russia’s central problem, offered a radically new solution through a unique combination of issues, and engaged in an uncompro- mising, negative campaign against his political opponents. This allowed Yeltsin to form an unusual coalition of different stripes and ideologies that resulted in his election as Russia’s ‹rst president. His rise to power, while certainly facilitated by favorable timing, should also be credited to his own political skill and strategic choices. In addition to the institutional reforms introduced at the June party conference, the summer of 1988 was marked by two other signi‹cant developments in Soviet politics. In August, Gorbachev presented a draft plan for the radical reorganization of the Secretariat, which was to be replaced by six commissions, each dealing with a speci‹c policy area. The Politburo’s adoption of this plan in September was a major politi- cal blow for Ligachev, who had used the Secretariat as his principal power base. Once viewed as the second most powerful man in the party, Ligachev now found himself chairman of the CC commission on agriculture, a position with little real in›uence.1 His ideological portfo- lio was transferred to Gorbachev’s ally, Vadim Medvedev, who 225 226 The Strategy of Campaigning belonged to the new group of soft-line reformers. His colleague Alexan- der Yakovlev assumed responsibility for foreign policy. -

Honecker's Policy Toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government Spring 1976 Contrast and Continuity: Honecker’s Policy toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin Stephen R. Bowers Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Stephen R., "Contrast and Continuity: Honecker’s Policy toward the Federal Republic and West Berlin" (1976). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 86. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/86 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 308 STEPHEN R. BOWERS 36. Mamatey, pp. 280-286. 37. Ibid., pp. 342-343. CONTRAST AND CONTINUITY: 38. The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Volume VIII (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954), p. 1364. 39. Robert Ferrell, 'The United States and East Central Europe Before 1941," in Kertesz, op. cit., p. 22. HONECKER'S POLICY 40. Ibid., p. 24. 41. William R. Caspary, 'The 'Mood Theory': A Study of Public Opinion and Foreign Policy," American Political Science Review LXIV (June, 1970). 42. For discussion on this point see George Kennan, American Diplomacy (New York: Mentor Books, 1951); Walter Lippmann, The Public Philosophy (New York: Mentor Books, TOWARD THE FEDERAL 1955). 43. Gaddis, p. 179. 44. Martin Wei!, "Can the Blacks Do for Africa what the Jews Did for Israel?" Foreign Policy 15 (Summer, 1974), pp. -

Download (355Kb)

CCJJ\1l\1Il S S I Ot-T OF THE ETif{OPEA!'J COI\JftvlUNI TIES SEC (91) 2145 final Brussels; 21 Nove~ber 1991 CONFERENCE Ct~ SECUR l TY AND CO<WERA T I ON I H EUROPE HELS l ~I FOLLOW-UP MEET I t-3G MARCH - JUNE 1992 Ccm:wllcation of the Com.=iss:Ion to the Council . •· ' :- ,·.· CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE HELSINKI FOLLOW-uP ~EET I NG MARCH - JUNE 1992 Communication of the Commission to the Council 1. Introduction L The fourth CSCE follow-up meeting (after Belgrade 1977/78, Madr ld 1980-83 and Vienna 1986-89) will be held In Helsinki, starting on March 24, 1992. It Is scheduled to last for three months. The meeting will, according to the Paris Charter, "allow the participating states to take stock of developments, review the Implementation of their commItments and consIder further steps In the CSCE process". The conference Is likely to be opened by Foreign Ministers and w111 conclude with a Summit In early July. 2. It wil I be the first occasion after the Paris Summit of November 1990 for the CSCE to undertake a global appreciation of the fundamental changes which have occured since 1989/90 In central and eastern Europe and In the Soviet Union. Helsinki will consider ways and means by which the economic and political reforms underway can be accelerated. 3. Recent changes In Europe demonstrate the need for a new approach in substantive areas of cooperation as well as effective decision-making In CSCE Institutions, notably the Council, supported by the Committee of Senior Officials. -

The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 28 Article 2 Issue 1 Winter 1995 Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P. Scharf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Scharf, Michael P. (1995) "Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol28/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Michael P. Scharf * Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Introduction .................................................... 30 1. Background .............................................. 31 A. The U.N. Charter .................................... 31 B. Historical Precedent .................................. 33 C. Legal Doctrine ....................................... 41 I. When Russia Came Knocking- Succession to the Soviet Seat ..................................................... 43 A. History: The Empire Crumbles ....................... 43 B. Russia Assumes the Soviet Seat ........................ 46 C. Political Backdrop .................................... 47 D. -

Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D

History Faculty Publications History 11-7-2014 Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle William D. Bowman Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bowman, William D. "Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle." Philly.com (November 7, 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/53 This open access opinion is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heroes of Berlin Wall Struggle Abstract When the Berlin Wall fell 25 years ago, on Nov. 9, 1989, symbolically signaling the end of the Cold War, it was no surprise that many credited President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for bringing it down. But the true heroes behind the fall of the Berlin Wall are those Eastern Europeans whose protests and political pressure started chipping away at the wall years before. East