Horses and Bridles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 K - Z Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society K - Z July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Wells Cathedral Library and Archives

GB 1100 Archives Wells Cathedral Library and Archives This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NR A 43650 The National Archives Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) WELLS CATHEDRAL LIBRARY READERS' HANDLIST to the ARCHIVES of WELLS CATHEDRAL comprising Archives of CHAPTER Archives of the VICARS CHORAL Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES Library PICTURES & RE ALIA 1 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) CONTENTS Page Abbreviations Archives of CHAPTER 1-46 Archives of the VICARS CHORAL 47-57 Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES 58-64 Library PICTURES 65-72 Library RE ALIA 73-81 2 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ABBREVIATIONS etc. HM C Wells Historical Manuscripts Commission, Calendar ofManuscripts ofthe Dean and Chapter of Wells, vols i, ii (1907), (1914) LSC Linzee S.Colchester, Asst. Librarian and Archivist 1976-89 RSB R.S.Bate, who worked in Wells Cathedral Library 1935-40 SRO Somerset Record Office 3 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ARCHIVES of CHAPTER Pages Catalogues & Indexes 3 Cartularies 4 Charters 5 Statutes &c. 6 Chapter Act Books 7 Chapter Minute Books 9 Chapter Clerk's Office 9 Chapter Administration 10 Appointments, resignations, stall lists etc. 12 Services 12 Liturgical procedure 13 Registers 14 Chapter and Vicars Choral 14 Fabric 14 Architect's Reports 16 Plans and drawings 16 Accounts: Communar, Fabric, Escheator 17 Account Books, Private 24 Accounts Department (Modern) 25 Estates: Surveys, Commonwealth Survey 26 Ledger Books, Record Books 26 Manorial Court records etc. -

Preface Introduction: the Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution

Notes Preface 1. M. Barone, Our First Revolution, the Remarkable British Upheaval That Inspired America’s Founding Fathers, New York, 2007; G. S. de Krey, Restoration and Revolution in Britain: A Political History of the Era of Charles II and the Glorious Revolution, London, 2007; P. Dillon, The Last Revolution: 1688 and the Creation of the Modern World, London, 2006; T. Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720, London, 2006; S. Pincus, England’s Glorious Revolution, Boston MA, 2006; E. Vallance, The Glorious Revolution: 1688 – Britain’s Fight for Liberty, London, 2007. 2. G. M. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, Oxford, 1950, p. 90. 3. W. A. Speck, Reluctant Revolutionaries, Englishmen and the Revolution of 1688, Oxford, 1988, p. 72. Speck himself wrote the petition ‘set off a sequence of events which were to precipitate the Revolution’. – Speck, p. 199. 4. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, p. 87. 5. J. R. Jones, Monarchy and Revolution, London, 1972, p. 233. Introduction: The Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution 1. A. Rumble, D. Dimmer et al. (compilers), edited by C. S. Knighton, Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series, of the Reign of Anne Preserved in the Public Record Office, vol. iv, 1705–6, Woodbridge: Boydell Press/The National Archives, 2006, p. 1455. 2. Great and Good News to the Church of England, London, 1705. The lectionary reading on the day of their imprisonment was from Two Corinthians and on their release was Acts chapter 12 vv 1–12. 3. The History of King James’s Ecclesiastical Commission: Containing all the Proceedings against The Lord Bishop of London; Dr Sharp, Now Archbishop of York; Magdalen-College in Oxford; The University of Cambridge; The Charter- House at London and The Seven Bishops, London, 1711, pp. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

Thomas Anson of Shugborough

Thomas Anson of Shugborough and The Greek Revival Andrew Baker October 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My interest in Thomas Anson began in 1982, when I found myself living in a cottage which had formerly been occupied by a seamstress on the Shugborough estate. In those days very little was known about him, just enough to suggest he was a person worth investigating, and little enough material available to give plenty of space for fantasy. In the early days, I was given a great deal of information about the background to 18th- century England by the late Michael Baigent, and encouragement by his friend and colleague Henry Lincoln (whose 1974 film for BBC’s “Chronicle” series, The Priest the Painter and the Devil introduced me to Shugborough) and the late Richard Leigh. I was grateful to Patrick, Earl of Lichfield, and Leonora, Countess of Lichfield, for their enthusiastic support. I presented my early researches at a “Holy Blood and Holy Grail” weekend at Shugborough. Patrick Lichfield’s step-grandmother, Margaret, Countess of Lichfield, provided comments on a particularly puzzling red-herring. Over the next twenty years the fantasies were deflated, but Thomas Anson remained an intriguing figure. I have Dr Kerry Bristol of Leeds University to thank for revealing that Thomas really was a kind of “eminence grise”, an influential figure behind the scenes of the 18th-century Greek Revival. Her 2006 conference at Shugborough was the turning point. The time was ripe for new discoveries. I wish to thank several researchers in different fields who provided important revelations along the way: Paul Smith, for the English translation from Chris Lovegrove, (former editor of the Journal of the Pendragon Society) of the first portion of Lady Anson’s letter referring to Honoré d’Urfé’s pastoral novel L’Astrée, written in French. -

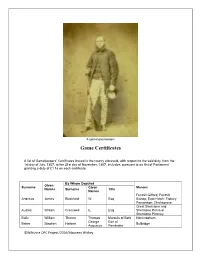

Game Certificates

A typical gamekeeper Game Certificates A list of Gamekeepers’ Certificates issued in the county aforesaid, with respect to the said duty, from the 1st day of July, 1807, to the 21st day of November, 1807, inclusive, pursuant to an Act of Parliament granting a duty of £1 1s on each certificate. By Whom Deputed Given Surname Given Manors Names Surname Title Names Fonthill Gifford; Fonthill Andrews James Blackford W. Esq. Bishop; East Hatch; Tisbury Parsonage; Chicksgrove Great Sherstone and Austen William Cresswell E. Esq. Sherstone Parva or Sherstone Pinkney Baily William Thynne Thomas Marquis of Bath Horningsham George Earl of Baker Stephen Herbert Bulbridge Augustus Pembroke ©Wiltshire OPC Project/2016/Maureen Withey Barnes William Wyndham W. Esq. Teffont Evias Littlecot with Rudge; Chilton Foliat with Soley; North Standen with Oakhill; & Charnham Street; with liberty Popham E. W. L. Esq. to kill game within the said manors of Littlecot with Rudge and Chilton Foliat with Soley Goddard A. Esq. Wither L. B. Esq. Northey W. Esq. Barrett Joseph Brudenell- Thomas Earl of Ailesbury Bruce Rev., D.D., Popham E. Clerk Froxfield Vilet T. G. Rev., Ll.d., Clerk Rt. Hon., Bruce C. B. commonly called Lord Bruce Goddard E. Rev., Clerk Michell T. Esq. Warneford F. Esq. North Tidworth; otherwise Batchelor Henry Poore E. Dyke Esq. Tidworth Zouch; and Figheldean Scrope W. Esq. Castle Coomb Beak William Sevington Vince H. C. Esq. Leigh-de-la-Mare Beck Thomas Astley F .D. Esq Boreham Pewsey; within the tithings of Beck William Astley F. D. Esq. Southcott and Kepnell Bennett John Williams S. -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

The Beginnings of the Library in Charles Town, South Carolina by Edgae Legake Pennington

1934.] The Library in Charles Town, So. Carolina 159 THE BEGINNINGS OF THE LIBRARY IN CHARLES TOWN, SOUTH CAROLINA BY EDGAE LEGAKE PENNINGTON HE lending library of colonial America owes most to T the industry and example of an English clergy- man, the Reverend Doctor Thomas Bray. Bray was born at Marton in Shropshire in 1656; after studying divinity at Oxford, he entered holy orders. He early attracted attention by his indefatigable zeal and great industry, and his interest in various reform movements. His energies led to his selection as a proper person to model the infant Church of England in the province of Maryland and establish it on a solid foundation. There had been a petition from that province for the assist- ance of a "superintendent, commissary, or suffragan"; 80, in April, 1696, Thomas Bray was appointed com- missary, or official representative of the Bishop of London who acted as diocesan of the Church in the American colonies. Bray was not able to go promptly. As he was impressed by the fact that it was difficult to secure the best ministers for the colonial field, he began to direct his efforts towards remedying such difficulties as might stand in the way. He found that the clergymen were usually too poor to buy books; and across the sea, shut off from educational opportunities, they must needs deteriorate. He laid the results of his enquiries before the bishops ; and declared that without a compe- tent provision of reading matter, the ministers could not prove useful to the design of their mission, and that a library would be the best encouragement to studious and sober men to enter the service.