Receivership: a Guide for Creditors (ASIC: Information Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

JUDGMENT CLAIMS IN RECEIVERSHIP PROCEEDINGS* JOHN K. BEACH Connecticuf Supreme Court of Errors In view of the importance of the subject it is unfortunate that so few of the reported cases on equitable receiverships of corporations have dealt in any comprehensive way with the principles underlying the administrating of the fund for the benefit of creditors. The result is that controversy has outstripped authoritative decision, and the subject is unsettled. To this generalization an exception must be noted in respect of the special topic of the application of current rail- way income to current expenses, before the payment of mortgage 1 indebtedness. On another disputed topic, the provability of imma.ure claims, the law, or at least the right principle of decision, has been settled, by the notable opinion of Judge Noyes in Pennsylvania Steel Company v. New York City Railway Company,2 followed and rein- forced by that of Mr. Justice Holmes in William Filene'sSons Company v. Weed.' Notwithstanding these important exceptions, the dearth of authority on the general subject is such that Judge Noyes refers to a case cited in his opinion as "almost the only case in which rules have "been formulated with respect to the provability of claims against "insolvent corporations."4 Upon the particular phase of the subject here discussed, the decisions are to some extent in conflict, and no attempt seems to have been made in text books or decisions to examine the question in the light of principle. Black, for example, dismisses the subject by saying it. is generally conceded that a receiver and the corporation whose property is under his charge "are so far in privity that a judgment against the * This paper deals only with judgments against the defendant in the receiver- ship, regarded as evidence of the validity and amount of the judgment creditor's claims for dividends to be paid out of the fund in the receiver's hands. -

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

CVA" Stands for a Number of Things, Including "Cerebro

COMPANY VOLUNTARY ARRANGEMENTS Michael Howlin, Q.C. Hastie Stable, Edinburgh 1. Introduction 1.1 The abbreviation "CVA" stands for a number of things, including "cerebro- vascular accident" (i.e., a stroke), "Creative Video Associations" (a company which recycles videotape), an organisation called "Croydon Voluntary Action", "credit value adjustment" (or indeed "counterparty valuation adjustment") in the context of banking, and a device known as a "controlled valve actuator". It also stands for "company voluntary arrangement", which is the subject-matter of this talk. 1.2 Recent high-profile examples of CVAs include those proposed by (the late) JJB Sports (for the second time), Blacks, Clinton Cards, PT McWilliams (a Northern Ireland engineering company), Oddbins (no explanation needed), Carvill Group (a Northern Ireland construction company) and McTavish 2 Ramsay, the Dundee door manufacturers. Even more recently, we have had the failed Glasgow Rangers CVA and CVAs for Travelodge and Fitness First. 2. The General Statutory Background 2.1 CVAs were created by the Insolvency Act 1986, which devoted all of seven sections to them. Since 2003, they have been governed by slightly expanded primary statutory provisions1 and a new Schedule (Schedule A1) to which I shall return shortly. There are also provisions in Part I of the Insolvency (Scotland) Rules 1986, as amended. 2.2 Section 1(1) defines a voluntary arrangement simply as "a composition in satisfaction of [the company's] debts or a scheme of arrangement of its affairs2". In practice, a CVA is a very flexible affair, the details of which will vary from case to case. Examples of what can be achieved by a CVA include: (1) unconditional foregiveness of debts, or certain classes of debts; (2) pro rata reduction (or partial reduction) of liabilities, or certain classes of liabilities; (3) other variations of liabilities (e.g. -

What a Creditor Needs to Know About Liquidating an Insolvent BVI Company

What a creditor needs to know about liquidating GUIDE an insolvent BVI company Last reviewed: October 2020 Contents Introduction 3 When is a company insolvent? 3 What is a statutory demand? 3 Written request for payment 3 Is it essential to serve a statutory demand? 3 What must a statutory demand say? 3 Setting aside a statutory demand 4 How may a company be put into liquidation? 4 Qualifying resolution 4 Appointment 4 Liquidator's powers 4 Court order 5 Who may apply? 5 Application 5 Debt should be undisputed 5 When does a company's liquidation start? 5 What are the consequences of a company being put into liquidation? 5 Assets do not vest in liquidator 5 Automatic consequences 5 Restriction on execution and attachment 6 Public documents 6 Other consequences 6 Effect on contracts 6 How do creditors claim in a company's liquidation? 7 Making a claim 7 Currency 7 Contingent debts 7 Interest 7 Admitting or rejecting claims 7 What is a creditors' committee? 7 Establishing the committee 7 2021934/79051506/1 BVI | CAYMAN ISLANDS | GUERNSEY | HONG KONG | JERSEY | LONDON mourant.com Functions 7 Powers 8 What is the order of distribution of the company's assets? 8 Pari passu principle 8 Excluded assets 8 Order of application 8 How are secured creditors affected by a company's liquidation? 8 General position 8 Liquidator challenge 8 Claiming in the liquidation 8 Who are preferential creditors? 9 Preferential creditors 9 Priority 9 What are the claims of current and past shareholders? 9 Do shareholders have to contribute towards the company's debts? -

Questionnaire for Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors*

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR OFFICIAL COMMITTEE OF UNSECURED CREDITORS* In Re: Please Type or Print Clearly. I am willing to serve on a Committee of Unsecured Creditors. Yes ( ) No ( ) A. Unsecured Creditor's Name and Contact Information: Name: ___________________________________________ Phone: __________________ Address: ___________________________________________ Fax: __________________ ___________________________________________ E-mail: _____________________________________________________________________________ B. Counsel (If Any) for Creditor and Contact Information: Name: ___________________________________________ Phone: __________________ Address: ___________________________________________ Fax: __________________ ___________________________________________ E-mail: _____________________________________________________________________________ C. If you have been contacted by a professional person(s) (e.g., attorney, accountant, or financial advisor) regarding the formation of this committee, please provide that individual’s name and/or contact information: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ D. Amount of Unsecured Claim (U.S. $) __________________________ E. Name of each debtor against whom you hold a claim: ____ __________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ ∗ Note: This is not a proof of claim form. Proof -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

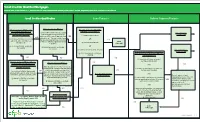

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich

Cornell Law Review Volume 19 Article 3 Issue 1 December 1933 Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Chester Rohrlich, Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations, 19 Cornell L. Rev. 35 (1933) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol19/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREDITOR CONTROL OF CORPORATIONS; OPERATING RECEIVERSHIPS; COR- PORATE REORGANIZATIONS* CHESTER RoHRmicnt A corporation is, on a smaller scale (in some instances on a larger scale), like the political state, in that beneath the cloak of its unity there is a continuous, at times active but more frequently passive, struggle for power among the various groups in interest. Some of these groups, such as the public that deals with it or the employees who work for it, have as yet achieved only the the barest minimum of legal right to control its destinies.' In the arena of the law, the traditional conflict is between the stockholders2 and the creditors. There is an increasing convergence of interest between these two groups as the former become more and more "investors" rather than entrepreneurs, and the latter less and less inclined, or able, to stand on the letter of their bond'3 both are in the last analysis dependent *This article is the substance of one of the chapters of the author's forthcoming book THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF CORPORATE CONTROL. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK for PUBLICATION ------X in Re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK FOR PUBLICATION --------------------------------------------------------X In re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L. HARTLEY, No. 09-37770 (CGM) Debtors. --------------------------------------------------------X JENNIFER ESPOSITO, Plaintiff, v. Adv. Pro. No. 10-9055 (CGM) RICHARD HARTLEY and KARA L. HARTLEY, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------------X APPEARANCES: DRAKE LOEB HELLER KENNEDY GOGERTY GABA & RODD, PLLC 555 Hudson Valley Avenue Suite 100 New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Stuart Kossar Attorneys for Plaintiff, Jennifer Esposito GREHER LAW OFFICES, P.C. 1161 Little Britain Road Suite B New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Warren Greher Attorney for the Defendants, Richard and Kara Hartley MEMORANDUM DECISION GRANTING PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGEMENT The plaintiff brings this adversary proceeding to except from discharge a judgment obtained against the defendants’ deli and catering business, Hartley’s Catering, Inc. (“Hartley’s Catering”). Because the defendants dissolved the corporation without giving plaintiff notice and opportunity to enforce her judgment against it, the defendants are jointly and severally liable for Page 1 of 12 on the judgment. The debt is non-dischargeable as property obtained by false pretenses, pursuant to section 523(a)(2)(A) and for failure to list the plaintiff in the petition pursuant to 523(a)(3). Background On November 13 2003, Hartley’s Catering was incorporated in the state of New York. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 1. On February 21, 2008, the New York State Commission of the Division of Human Rights found Hartley’s Catering d/b/a Schlesinger’s Deli Depot, liable to the plaintiff in the amount of $300,000. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 50. -

Bankruptcy a Guide for Unsecured Creditors Association Ofbusiness Recoveryprofessionals BANKRUPTCY BANKRUPTCY

Bankruptcy a guide for unsecured creditors Association ofBusiness RecoveryProfessionals BANKRUPTCY BANKRUPTCY Who can be made bankrupt? Bankruptcy An individual Only individuals can be made bankrupt. Bankruptcy does not apply to companies or partnerships, although individual members of a is made bankrupt as a result partnership can be made bankrupt. of a petition presented to How is an individual made bankrupt? Only individuals An individual is made bankrupt as a result of a can be made the court, usually because petition presented to the court, usually because bankrupt he cannot pay his debts. The debtor, one or more of his creditors or the supervisor of a he cannot pay his debts. voluntary arrangement, amongst others, may present a bankruptcy petition. A licensed insolvency practitioner has given you this The purpose of the bankruptcy order is to appoint a responsible because you, or your business, may be owed money person who has a duty to collect the bankrupt's assets and by a private individual or a sole trader who has distribute them to his creditors in accordance with the law. become bankrupt. This guide aims to help you understand your rights Who is appointed to deal with the bankrupt’s estate? as a creditor and to describe how best these rights Once a bankruptcy order is made, the court will usually appoint the Official Receiver to administer a bankrupt’s estate. The Official can be exercised. It is intended to relate only to Receiver is a civil servant and an officer of the court. The Official England and Wales. It is not an exhaustive statement Receiver must then decide within twelve weeks of the bankruptcy of the relevant law or a substitute for specific order whether to call a meeting of creditors to appoint a licensed professional or legal advice. -

The Unsecured Creditor's Bargain: a Reply, 80 Va

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1994 The nsecU ured Creditor's Bargain: A Reply Susan Block-Lieb Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susan Block-Lieb, The Unsecured Creditor's Bargain: A Reply, 80 Va. L. Rev. 1989 (1994) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/740 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNSECURED CREDITOR'S BARGAIN: A REPLY Susan Block-Lieb* INTRODUCTION U UNLIKE Law and Economics scholars who view secured lend- ing as a consensual relationship benefiting not only debtors and their secured parties but also the debtors' unsecured creditors, Lynn LoPucki describes secured transactions as a subsidy because they benefit debtors and their secured creditors at the expense of unsecured creditors. He believes security "is an institution in need of basic reform" because it "tends to misallocate resources by imposing on unsecured creditors a bargain to which many, if not most, of them have given no meaningful consent."' He divides these unsecured creditors into two groups: involuntary creditors, and -

Contracting out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: the Main Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 In

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 12 2014 Contracting Out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: The ainM Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 in the Proposal to Amend the EU Insolvency Regulation Bob Wessels Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation Bob Wessels, Contracting Out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: The Main Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 in the Proposal to Amend the EU Insolvency Regulation, 9 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2014). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol9/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. CONTRACTING OUT OF SECONDARY INSOLVENCY PROCEEDINGS: THE MAIN LIQUIDATOR’S UNDERTAKING IN THE MEANING OF ARTICLE 18 IN THE PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE EU INSOLVENCY REGULATION Prof. Dr. Bob Wessels* INTRODUCTIOn The European Insolvency Regulation1 aims to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of insolvency proceedings having cross-border effects within the European Union. For that purpose, the Insolvency Regulation lays down rules on jurisdiction common to all member states of the European Union (Member States), rules to facilitate recognition of insolvency judgments, and rules regarding the applicable law. The model of the Regulation will be known. It allows for one main proceeding, opened in one Member State, with the possibility of opening secondary proceedings in other EU Member States. The procedural model can only be successful if these proceedings are coordinated: Main insolvency proceedings and secondary proceedings can…contribute to the effective realization of the total assets only if all the concurrent proceedings pending are coordinated.