The First Guide Meridian East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 4310-22-P DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Bureau of Land

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 06/22/2015 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2015-15241, and on FDsys.gov 1 4310-22-P DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management [LLWY-9570000-15-L13100000-PP0000] Filing of Plats of Survey, Wyoming and Nebraska AGENCY: Bureau of Land Management, Interior. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has filed the plats of survey of the lands described below in the BLM Wyoming State Office, Cheyenne, Wyoming, on the dates indicated. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Bureau of Land Management, 5353 Yellowstone Road, P.O. Box 1828, Cheyenne, Wyoming 82003. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: These supplementals and surveys were executed at the request of the U. S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Reclamation and are necessary for the management of resources. The lands surveyed are: The plats and field notes representing the dependent resurvey of portions of the north boundary, certain tracts and subdivisional lines, the survey of the subdivision of certain sections, and the metes-and-bounds survey of the Raymond Mountain Wilderness Study Area boundary, Township 25 North, Range 119 West, Sixth Principal Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 861, was accepted February 26, 2015. 2 The plat and field notes representing the dependent resurvey of a portion of the south boundary and a portion of the subdivisional lines, and the survey of the subdivision of section 35, Township 26 North, Range 73 West, Sixth Principal Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 891, was accepted February 26, 2015. -

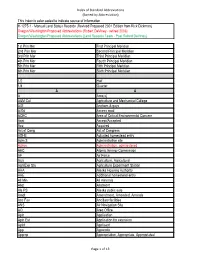

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index Is Color Coded to Indicate Source of Information

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index is color coded to indicate source of information. H-1275-1 - Manual Land Status Records (Revised Proposed 2001 Edition from Rick Dickman) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Robert DeViney - retired 2006) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Land Records Team - Post Robert DeViney) 1st Prin Mer First Principal Meridian 2nd Prin Mer Second Principal Meridian 3rd Prin Mer Third Principal Meridian 4th Prin Mer Fourth Principal Meridian 5th Prin Mer Fifth Principal Meridian 6th Prin Mer Sixth Principal Meridian 1/2 Half 1/4 Quarter A A A Acre(s) A&M Col Agriculture and Mechanical College A/G Anchors & guys A/Rd Access road ACEC Area of Critical Environmental Concern Acpt Accept/Accepted Acq Acquired Act of Cong Act of Congress ADHE Adjusted homestead entry Adm S Administrative site Admin Administration, administered AEC Atomic Energy Commission AF Air Force Agri Agriculture, Agricultural Agri Exp Sta Agriculture Experiment Station AHA Alaska Housing Authority AHE Additional homestead entry All Min All minerals Allot Allotment Als PS Alaska public sale Amdt Amendment, Amended, Amends Anc Fas Ancillary facilities ANS Air Navigation Site AO Area Office Apln Application Apln Ext Application for extension Aplnt Applicant App Appendix Approp Appropriation, Appropriate, Appropriated Page 1 of 13 Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) Appvd Approved Area Adm O Area Administrator Order(s) Arpt Airport ARRCS Alaska Rural Rehabilitation Corp. sale Asgn Assignment -

Sixth Principal Meridian Tale of Two Townships Decided Guidance Cast Iron Monument Boundary Principles Part 3: Dissent CAST IRON MONUMENT of the 6Th P.M

JULY 2017 DRONES! Sixth Principal Meridian Tale of Two Townships Decided Guidance Cast Iron Monument Boundary principles Part 3: Dissent CAST IRON MONUMENT of the 6th P.M. idden from view among the 108-mile distance was due to the expediency of trees on a high bluff along the the surveys because settlement was already taking west side of the Missouri River place in eastern portions of the two territories. The is a monument on the Kansas/ distance was divisible by six, and it was thought to Nebraska state line that has be at the western edge of hostile interruptions from Hbeen overlooked in terms of importance. It was the the plains Indians. beginning point for the surveys of the 6th Principal The contract for the base line was given to John Meridian, yet throughout its 152 year existence, P. Johnson, a 37-year-old Harvard graduate who its designation has simply been the “Cast Iron had vied for the surveyor general position against Monument”. Calhoun. To appease Johnson for not getting the posi- On August 24, 1854, General Land Office tion, Calhoun was pressured to give him the contract Commissioner John Wilson sent instructions to the for the important line despite some misgivings about Kansas/Nebraska Territory Surveyor General John his competency. Ensuring that Johnson properly Calhoun to have the 40° north latitude surveyed a started the base line, Thomas J. Lee of the Corps of distance of 108 miles west from the Missouri River Topographical Engineers was hired to make the nec- as the base line for the 6th Principal Meridian essary astronomical observations to place a point on surveys. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 136/Friday, July 14, 2000/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 136 / Friday, July 14, 2000 / Notices 43781 Sec. 19, lots 5 to 13, inclusive; survey of section 1 and a metes-and- subdivisional lines and portions of Sec. 30, lots 5 to 18, inclusive; bounds survey in section 1, T. 1 N., R. certain mineral surveys the subdivision Sec. 31, lots 5 to 15, inclusive. 73 W., Sixth Principal Meridian, Group of section 28, and the remonumentation T. 49 N., R. 93 W., 875, Colorado, was accepted April 26, of certain original corners, T. 20 S., R. Sec. 12, NW1¤4NW1¤4, S1¤2NW1¤4, SW1¤4, 2000. 71 W., Sixth Principal Meridian, Group NW1¤4SE1¤4, and S1¤2SE1¤4; Secs. 13, 24, 25, and 36. The plat representing the dependent 1209, Colorado, was accepted June 5, The area described contains 4,536.29 acres resurvey of portions of the east 2000. in Big Horn County. boundary, subdivisional lines, and The plat representing the dependent certain homestead entry surveys, and resurvey of a portion of the east 3. The remaining lands, which the subdivision of certain sections in T. comprise 2,480 acres, have been boundary, subdivisional lines, and the 11 N., R. 102 W., Sixth Principal subdivision of section 13, and the conveyed out of Federal ownership and Meridian, Group 1219, Colorado, was this is a record-clearing action only. A subdivision of a portion of section 13, accepted April 14, 2000. T. 1 S., R. 2 E., Ute Meridian, Group more specific legal description of these The plat representing the dependent private lands may be obtained by 1204, Colorado, was accepted May 24, resurvey of portions of the subdivisional 2000. -

The Ohio Surveys

Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Report on the Investigation of the FGDC Cadastral Data Content Standard and its Applicability in Support of the Ohio Survey Systems Nancy von Meyer Fairview Industries, Inc For The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) National Integrated Land System (NILS) Project Office January 2005 i Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Preface Ohio was the testing and proving grounds of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS). As a result Ohio contains many varied land descriptions and survey systems. Further complicating the Ohio land description scene are large federal tracts reserved for military use and lands held by other states prior to Ohio statehood. This document is not a history of the land system development for Ohio. The history of Ohio surveys can be found in other materials including the following: Downs, Randolf C., 1927, Evolution of Ohio County Boundaries”, Ohio Archeological and Historical Publications Number XXXVI, Columbus, Ohio. Reprinted in 1970. Gates, Paul W., 1968. “History of Public Land Law Development”, Public Land Law Review Commission, Washington DC. Knepper, George, 2002, “The Official Ohio Lands Book” Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. http://www.auditor.state.oh.us/StudentResources/OhioLands/ohio_lands.pdf Last Accessed November 2, 2004 Petro, Jim, 1997, “Ohio Lands A Short History”, Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. Sherman, C.E., 1925, “Original Ohio Land Subdivisions” Volume III of the Final Report to the Ohio Cooperative Topographic Survey. Reprinted in 1991. White, Albert C., “A History of the Public Land Survey System”, US Government Printing Office, Stock Number 024-011-00150-6, Washington D.C. -

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I Have Hereunto Set My Hand and Caused the Seal of the United States of America to Be Affixed

73 STAT.] PROOLAMATIONS^AUG. 7, 1959 C69 IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the United States of America to be affixed. DONE at the City of Washington this fourth day of August in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and fifty-nine, and [SEAL] of the Independence of the United States of America the one hundred and eighty-fourth. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER By the President: DOUGLAS DILLON, Acting Secretary of State. EXCLUDING CERTAIN LANDS FROM AND ADDING CERTAIN LANDS TO THE COLORADO NATIONAL MONUMENT _ -^ „ . August 7, 1959 BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES or AMERICA [NO. 3307] A PROCLAMATION WHEREAS it appears that it would be in the public interest to exclude from the Colorado National Monument, in Colorado, certain lands which are not necessary for the proper care, management, and protection of the objects of scientific interest situated on the lands within the monument; and WHEREAS it appears that it would also be in the public interest to add to such monument certain adjoining public lands and lands donated to the United States which are needed for administrative purposes and for the proper care, management, and protection of the objects of scientific interest situated on lands now within the monument: NOW, THEREFORE, I, DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER, Presi dent of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by section 2 of the act of June 8, 1906, 34 Stat. 225 (16 U.S.C. 431), do proclaim as follows: The following-described lands in the State of Colorado are hereby excluded from the Colorado National Monument: SIXTH PRINCIPAL MERIDIAN T. -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 123/Wednesday, June 28, 2017

29318 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 123 / Wednesday, June 28, 2017 / Notices FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: before the scheduled date of official Forest Service and the BLM, are Sonja Sparks, BLM Wyoming Cadastral filing for the plat(s) of survey being necessary for the management of these Surveyor at 307–775–6222 or s75spark@ protested. Any notice of protest filed lands. blm.gov. Persons who use a after the scheduled date of official filing DATES: Unless this action is protested, telecommunications device for the deaf will be untimely and will not be the plats described in this notice will be may call the Federal Relay Service at 1– considered. A notice of protest is filed on July 28, 2017. 800–877–8339 to contact this office considered filed on the date it is ADDRESSES: You may submit written during normal business hours. The received by the State Director during protests to the BLM Colorado State Service is available 24 hours a day, 7 regular business hours; if received after Office, Cadastral Survey, 2850 days a week, to leave a message or regular business hours, a notice of Youngfield Street, Lakewood, CO question with this office. You will protest will be considered filed the next 80215–7093. receive a reply during normal business business day. A written statement of FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: hours. reasons in support of a protest, if not Randy Bloom, Chief Cadastral Surveyor SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The lands filed with the notice of protest, must be for Colorado; (303) 239–3856; rbloom@ surveyed are: The plat representing the filed with the State Director within 30 blm.gov. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 196 / Thursday, October 9, 1997 / Notices

52768 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 196 / Thursday, October 9, 1997 / Notices Sec. 11, N1¤2 and N1¤2SW1¤4; laws, including the United States Mount Diablo Meridian, California 1 1 Sec. 12, NW ¤4NW ¤4; mining laws (30 U.S.C. Ch. 2), but not T. 16 N., R. 10 E.ÐSupplemental plat of the 1 1 1 1 Sec. 15, N ¤2NE ¤4, SW ¤4NE ¤4, 1 from leasing under the mineral leasing SE ¤4 of section 22, accepted September 1 1 1 1 NW ¤4NW ¤4, and E ¤2W ¤2. laws, for the Fish and Wildlife Service 18, 1997, to meet certain administrative T. 3 N., R. 72 W., to preserve the integrity of the wetlands needs of the US Forest Service, Tahoe Sec. 15, lots 13 and 14; National Forest. Sec. 21, lots 8 and 9; and surrounding uplands and offer a sanctuary to wildlife at the Crescent T. 18 N., R. 10 E.ÐSupplemental plat of Sec. 24, lots 2, 4, and 8. section 33 and the W 1¤2 of section 34, T. 3 N., R. 73 W., Lake National Wildlife Refuge: accepted September 22, 1997, to meet 1 1 Sec. 12, SW ¤4SE ¤4; Sixth Principal Meridian, Nebraska certain administrative needs of the BLM, Sec. 13, W1¤2NE1¤4, E1¤2NW1¤4, and T. 22 N., R. 47 W., Bakersfield District, Folsom Resource Area. NE1¤4SW1¤4. Sec. 1, lots 10 to 13, inclusive, and lot 16; All of the above listed survey plats are The areas described aggregate 3,815.40 Sec. -

Specifications for Descriptions of Land: for Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases

United States Department of the Interior • Bureau of Land Management • Cadastral Survey Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases Revised 2017 Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases Produced in coordination with the Office of Management and Budget, United States Federal Geographic Data Committee, Cadastral Subcommittee Washington, DC: 2015; Revised 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior Suggested citation for general reference: U.S. Department of the Interior. 2017. Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases. Bureau of Land Management. Washington, DC. Suggested citation for technical reference: Specifications for Descriptions of Land (2017) Find these Specifications and other information at www.blm.gov. Printed copies are available from: Printed Materials Distribution Services Fax: 303-236-0845 Email: [email protected] Stock Number: P-474 BLM/WO/GI-17/007+1813 U.S. Department of the Interior The mission of the Department of the Interior (Department) is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and our commitments to island communities. The Department works to assure the wisest choices are made in managing all of the Nation’s resources so each will make its full contribution to a better United States—now and in the future. The Department manages about 500 million acres, or one-fifth, of the land in the United States. -

18. Geologic Terms and Geographic Divisions

18. Geologic Terms and Geographic Divisions Geologic terms For capitalization, compounding, and use of quotations in geologic terms, copy is to be followed. Geologic terms quoted verbatim from published ma- terial should be left as the original author used them; however, it should be made clear that the usage is that of the original author. Formal geologic terms are capitalized: Proterozoic Eon, Cambrian Period. Structural terms such as arch, anticline, or uplift are capitalized when pre- ceded by a name: Cincinnati Arch, Cedar Creek Anticline, Ozark Uplift . See Chapter 4 geographic terms for more information. Divisions of Geologic Time [Most recent to oldest] Eon Era Period Phanerozoic ................ Cenozoic ............................ Quarternary. Tertiary (Neogene, Paleogene). Mesozoic........................... Cretaceous. Jurassic. Triassic. Paleozoic .......................... Permian. Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian, Mississippian). Devonian. Silurian. Ordovician. Cambrian. Proterozoic ................. Neoproterozoic ............... Ediacaran. Cryogenian. Tonian. Mesoproterozoic ............. Stenian. Ectasian. Calymmian. Paleoproterozoic ............. Statherian. Orosirian. Rhyacian. Siderian. Archean ....................... Neoarchean. Mesoarchean. Paleoarchean. Eoarchean. Hadean. Source: Information courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey; for graphic see http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3015/ fs2007-3015.pdf. 343 cchapter18.inddhapter18.indd 334343 111/13/081/13/08 3:19:233:19:23 PPMM 344 Chapter 18 Physiographic regions Physiographic -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 16/Wednesday, January 25, 2012

3792 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 16 / Wednesday, January 25, 2012 / Notices The plat representing the dependent Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 842, The field notes representing the resurvey of portions of the west was accepted September 29, 2011. remonumentation of the 1⁄4 sec. cor. of boundary, subdivisional lines, and the The plat and field notes representing secs. 31 and 32, Township 44 North, original meanders of North Lake, and the dependent resurvey of a portion of Range 76 West, Sixth Principal the partial subdivision of section 7, and the north boundary, a portion of the Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 850, the metes-and-bounds survey of Lot 19, subdivisional lines and the subdivision was accepted November 3, 2011. section 7, Township 14 South, Range 44 of sections 4 and 10, Township 57 The plat and field notes representing East, of the Boise Meridian, Idaho, North, Range 101 West, Sixth Principal Group Number 1357, was accepted Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 816, the dependent resurvey of a portion of November 4, 2011. was accepted October 4, 2011. the subdivisional lines and the survey of The supplemental plat showing the subdivision of section 33, Township SUMMARY: The Bureau of Land amended lottings, Township 41 North, 26 North, Range 105 West, Sixth Management (BLM) will file the plat of Range 71 West, Sixth Principal Principal Meridian, Wyoming, Group survey of the lands described below in Meridian, Wyoming, Group No. 852, the BLM Idaho State Office, Boise, No. 823, was accepted November 3, was accepted October 12, 2011 and Idaho, 30 days from the date of 2011. -

A Prac Cal Guide to Understanding Land Descrip

By Gary Hanson, Stumbo Hanson, LLP Alan Soelter, Bartlett & West, Inc. A Praccal Guide to Understanding Land Descripons ublic water supply and wastewater systems provide The “Grid” – sections, townships and ranges service to land for the use of their customers. Townships and Ranges are located in relation to two A PPraccalPersons working with these systems Guide need to todifferent typesUnderstanding of survey lines. The first of these is called understand how that land is described. But these a “baseline”, which runs east and west. The second type descriptions are written in a language foreign to most of survey line runs north and south and is called a people. This article will provide a basic understanding of “principal meridian”. The principal meridian running Landthe components Descripons of legal descriptions, what they mean, through Kansas is called the Sixth Principal Meridian. It and how to become more comfortable when confronted intersects the Kansas/Nebraska border about nineteen with such descriptions. This article is written for Kansans miles west of Washington and extends south to the and is specific to real estate descriptions in Kansas. Oklahoma border. The diagram below shows the relationship of Townships and Ranges to baselines and History of legal descriptions principal meridians. Legal descriptions, as we know them, came about when Diagram 1 shows that starting from the intersection of a the federal government issued the original land grants. In baseline and a principal meridian, Township Lines and order for the federal government to issue the grants, there Range Lines lay out a grid of approximately six-mile had to be a means to describe the land.