Measuring Snow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter Storm Information That Is Useful to the Public

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter storm information that is useful to the public: 1) The time of onset of dangerous winter weather conditions 2) The time that dangerous winter weather conditions will abate 3) The type of winter weather to be expected: a) Snow b) Sleet c) Freezing rain d) Transitions between these three 7) The intensity of the precipitation 8) The total amount of precipitation that will accumulate 9) The temperatures during the storm (particularly if they are dangerously low) 7) The winds and wind chill temperature (particularly if winds cause blizzard conditions where visibility is reduced). 8) The uncertainty in the forecast. Some problems facing meteorologists: Winter precipitation occurs on the mesoscale The type and intensity of winter precipitation varies over short distances. Forecast products are not well tailored to winter Subtle features, such as variations in the wet bulb temperature, orography, urban heat islands, warm layers aloft, dry layers, small variations in cyclone track, surface temperature, and others all can influence the severity and character of a winter storm event. FORECASTING WINTER WEATHER Important factors: 1. Forcing a) Frontal forcing (at surface and aloft) b) Jetstream forcing c) Location where forcing will occur 2. Quantitative precipitation forecasts from models 3. Thermal structure where forcing and precipitation are expected 4. Moisture distribution in region where forcing and precipitation are expected. 5. Consideration of microphysical processes Forecasting winter precipitation in 0-48 hour time range: You must have a good understanding of the current state of the Atmosphere BEFORE you try to forecast a future state! 1. Examine current data to identify positions of cyclones and anticyclones and the location and types of fronts. -

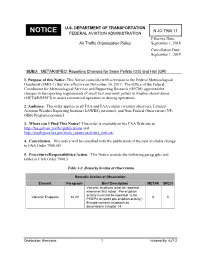

METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7900.11 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Effective Date: Air Traffic Organization Policy September 1, 2018 Cancellation Date: September 1, 2019 SUBJ: METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR) 1. Purpose of this Notice. This Notice coincides with a revision to the Federal Meteorological Handbook (FMH-1) that was effective on November 30, 2017. The Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OFCM) approved the changes to the reporting requirements of small hail and snow pellets in weather observations (METAR/SPECI) to assist commercial operators in deicing operations. 2. Audience. This order applies to all FAA and FAA-contract weather observers, Limited Aviation Weather Reporting Stations (LAWRS) personnel, and Non-Federal Observation (NF- OBS) Program personnel. 3. Where can I Find This Notice? This order is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and http://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Cancellation. This notice will be cancelled with the publication of the next available change to FAA Order 7900.5D. 5. Procedures/Responsibilities/Action. This Notice amends the following paragraphs and tables in FAA Order 7900.5. Table 3-2: Remarks Section of Observation Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Volcanic eruptions must be reported whenever first noted. Pre-eruption activity must not be reported. (Use Volcanic Eruptions 14.20 X X PIREPs to report pre-eruption activity.) Encode volcanic eruptions as described in Chapter 14. Distribution: Electronic 1 Initiated By: AJT-2 09/01/2018 N JO 7900.11 Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Whenever tornadoes, funnel clouds, or waterspouts begin, are in progress, end, or disappear from sight, the event should be described directly after the "RMK" element. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

A Meteorological and Blowing Snow Data Set (2000–2016) from a High-Elevation Alpine Site (Col Du Lac Blanc, France, 2720 M A.S.L.)

Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 11, 57–69, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-11-57-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A meteorological and blowing snow data set (2000–2016) from a high-elevation alpine site (Col du Lac Blanc, France, 2720 m a.s.l.) Gilbert Guyomarc’h1,5, Hervé Bellot2, Vincent Vionnet1,3, Florence Naaim-Bouvet2, Yannick Déliot1, Firmin Fontaine2, Philippe Puglièse1, Kouichi Nishimura4, Yves Durand1, and Mohamed Naaim2 1Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Université de Toulouse, Météo-France, CNRS, CNRM, Centre d’Etudes de la Neige, Grenoble, France 2Univ. Grenoble Alpes, IRSTEA, UR ETNA, 38042 St-Martin-d’Hères, France 3Centre for Hydrology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 4Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan 5Météo France, DIRAG, Point à Pitre, Guadeloupe, France Correspondence: Florence Naaim-Bouvet (fl[email protected]) Received: 12 June 2018 – Discussion started: 25 June 2018 Revised: 8 October 2018 – Accepted: 9 November 2018 – Published: 11 January 2019 Abstract. A meteorological and blowing snow data set from the high-elevation experimental site of Col du Lac Blanc (2720 m a.s.l., Grandes Rousses mountain range, French Alps) is presented and detailed in this pa- per. Emphasis is placed on data relevant to the observations and modelling of wind-induced snow transport in alpine terrain. This process strongly influences the spatial distribution of snow cover in mountainous terrain with consequences for snowpack, hydrological and avalanche hazard forecasting. In situ data consist of wind (speed and direction), snow depth and air temperature measurements (recorded at four automatic weather stations), a database of blowing snow occurrence and measurements of blowing snow fluxes obtained from a vertical pro- file of snow particle counters (2010–2016). -

Chemical Properties of Snow Cover As an Impact Indicator for Local Air Pollution Sources

INFRASTRUKTURA I EKOLOGIA TERENÓW WIEJSKICH INFRASTRUCTURE AND ECOLOGY OF RURAL AREAS No IV/2/2017, POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, Cracow Branch, pp. 1591–1607 Commission of Technical Rural Infrastructure DOI: http://dx.medra.org/10.14597/infraeco.2017.4.2.120 CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF SNOW COVER AS AN IMPACT INDICATOR FOR LOCAL AIR POLLUTION SOURCES Krzysztof Jarzyna, Rafał Kozłowski, Mirosław Szwed Jan Kochanowski University Abstract In this article, selected physical and chemical properties of water originating from melted snow collected in the area of the city of Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski (Poland) in January 2017 were determined. The analysed samples of snow were collected at 18 measurement sites located along the axis of cardinal directions of the world and with a central point in the urban area of Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski in January 2017. Chemical com- position was determined using the Dionex ICS 3000 Ion Chromatograph at the Environmental Research Laboratory of the Chair of Environmental Protection and Modelling at the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce. The obtained results indicated a substantial contribution of pollutants pro- duced by a local steelworks in the chemical composition of melted snow. Keywords: precipitation chemistry, anthropopressure, snow cover INTRODUCTION The use of snow cover as an indicator for the magnitude of deposition of atmospheric air pollutants has already had several decades of tradition in Poland and Europe (Engelhard et al. 2007, Kozłowski et al. 2012, Siudek et al. 2015, Stachnik et al. 2010,). The snow cover proves itself as an efficient collector of airborne pollutants which allows for quick and efficient estimation of airborne pollution concentrations over the entire period of lingering snow cover occur- This is an open access article under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc-nd/4.0/) 1591 Krzysztof Jarzyna, Rafał Kozłowski, Mirosław Szwed rence. -

Accuracy of NWS 8 Standard Nonrecording Precipitation Gauge

54 JOURNAL OF ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 15 Accuracy of NWS 80 Standard Nonrecording Precipitation Gauge: Results and Application of WMO Intercomparison DAQING YANG,* BARRY E. GOODISON, AND JOHN R. METCALFE Atmospheric Environment Service, Downsview, Ontario, Canada VALENTIN S. GOLUBEV State Hydrological Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia ROY BATES AND TIMOTHY PANGBURN U.S. Army CRREL, Hanover, New Hampshire CLAYTON L. HANSON U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Northwest Watershed Research Center, Boise, Idaho (Manuscript received 21 December 1995, in ®nal form 1 August 1996) ABSTRACT The standard 80 nonrecording precipitation gauge has been used historically by the National Weather Service (NWS) as the of®cial precipitation measurement instrument of the U.S. climate station network. From 1986 to 1992, the accuracy and performance of this gauge (unshielded or with an Alter shield) were evaluated during the WMO Solid Precipitation Measurement Intercomparison at three stations in the United States and Russia, representing a variety of climate, terrain, and exposure. The double-fence intercomparison reference (DFIR) was the reference standard used at all the intercomparison stations in the Intercomparison project. The Intercomparison data collected at different sites are compatible with respect to the catch ratio (gauge measured/DFIR) for the same gauges, when compared using wind speed at the height of gauge ori®ce during the observation period. The effects of environmental factors, such as wind speed and temperature, on the gauge catch were investigated. Wind speed was found to be the most important factor determining gauge catch when precipitation was classi®ed into snow, mixed, and rain. The regression functions of the catch ratio versus wind speed at the gauge height on a daily time step were derived for various types of precipitation. -

Snow to Water Ratios 88

Snow to Water Ratios 88 The amount of snow from a storm can look impressive when it covers your house and cars, but if you melted the snow you would discover that very little water is actually involved. The 'snow to ice ratio' or Snow Ratio expresses how much volume of snow you get for a given volume of water. Typically a ratio of 10:1 (ten to one) means that every 10 inches of snowfall equals one inch of liquid water. Problem 1 - During a winter storm called 'Snowmageddon' in 2010, the Washington DC region received about 24 inches of snow fall. If this was dry, uncompacted snow, about how many inches of rain would this equal if the Snow Ratio was 10:1 ? Problem 2 - The Snow Ratio depends on the temperature of the air as shown in the table below: o o o o o o Temp (F) 30 25 18 12 5 -10 Ratio 10:1 15:1 20:1 30:1 40:1 50:1 o If 30 inches of snow fell in Calgary, Alberta at 18 F, and 25 inches of snow fell in o Denver, Colorado where the temperature was 25 F, at which location would the most water have fallen? Space Math http://spacemath.gsfc.nasa.gov Answer Key 88 Problem 1 - During a winter storm called 'Snowmageddon' in 2010, the Washington DC region received about 24 inches of snow fall. If this was dry, uncompacted snow, about how many inches of rain would this equal if the Snow Ratio was 10:1 ? Answer: 24 inches of snow x (1 inch water/10 inches of snow) = 2.4 inches of water. -

Snow Removal Brochure

LEHI CITY SNOW REMOVAL A Guide to Managing Winter Storms THE LEHI CITY STREETS DIVISION’S PRIORITY IS TO PROVIDE THE SAFEST POSSIBLE DRIVING CONDITIONS. SNOW REMOVAL IS DEPENDENT ON A NUMBER OF FACTORS, INCLUDING THE TIMING AND DURATION OF A SNOWSTORM AND THE DENSITY OF THE SNOW. THIS GUIDE PROVIDES RESIDENTS WITH INFORMATION ABOUT THE SNOW REMOVAL PROGRAM AND SETS EXPECTATIONS DURING AND AFTER A STORM. SNOW CONDITIONS The Lehi City Streets Division makes it a priority to be responsive during and immediately after a storm. Response time to individual streets and neighborhoods will depend on several factors, including timing and duration of the storm. TIMING Crews will make every effort to keep major streets clear of snow and ice. Heavily traveled roads and bus routes will receive top priority to ensure everyone’s safety. Once major commuter roads have been deemed safe for travel, secondary and side streets will be cleared. During evening and early morning storms, crews should have ample time to prepare for commuting hours. Plows will continue to clean, treat, and widen roadways until reasonably safe conditions are met. DURATION The duration of a storm plays an important role in snow plowing operations. Storms of extended duration require all available resources to keep roads open over an extended period of time. A snow storm of four inches over a 24-hour period will require more time and man hours than a storm of six inches over an 8-hour period. Please keep in mind that plows are still hard at work well after the snow has stopped falling. -

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

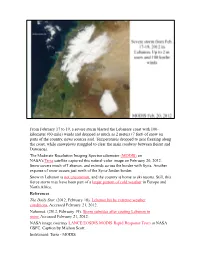

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream. -

Hazard Mitigation Plan – Dutchess County, New York 5.4.1-1 December 2015 Section 5.4.1: Risk Assessment – Coastal Hazards

Section 5.4.1: Risk Assessment – Coastal Hazards 5.4.1 Coastal Hazards 7KH IROORZLQJ VHFWLRQ SURYLGHV WKH KD]DUG SURILOH KD]DUG GHVFULSWLRQ ORFDWLRQ H[WHQW SUHYLRXV RFFXUUHQFHV DQG ORVVHV SUREDELOLW\ RI IXWXUH RFFXUUHQFHV DQG LPSDFW RI FOLPDWH FKDQJH DQG YXOQHUDELOLW\ DVVHVVPHQW IRU WKH FRDVWDO KD]DUGV LQ 'XWFKHVV &RXQW\ 3URILOH +D]DUG 'HVFULSWLRQ $ WURSLFDO F\FORQH LV D URWDWLQJ RUJDQL]HG V\VWHP RI FORXGV DQG WKXQGHUVWRUPV WKDW RULJLQDWHV RYHU WURSLFDO RU VXEWURSLFDO ZDWHUV DQG KDV D FORVHG ORZOHYHO FLUFXODWLRQ 7URSLFDO GHSUHVVLRQV WURSLFDO VWRUPV DQG KXUULFDQHV DUH DOO FRQVLGHUHG WURSLFDO F\FORQHV 7KHVH VWRUPV URWDWH FRXQWHUFORFNZLVH DURXQG WKH FHQWHU LQ WKH QRUWKHUQ KHPLVSKHUH DQG DUH DFFRPSDQLHG E\ KHDY\ UDLQ DQG VWURQJ ZLQGV 1:6 $OPRVW DOO WURSLFDO VWRUPV DQG KXUULFDQHV LQ WKH $WODQWLF EDVLQ ZKLFK LQFOXGHV WKH *XOI RI 0H[LFR DQG &DULEEHDQ 6HD IRUP EHWZHHQ -XQH DQG 1RYHPEHU KXUULFDQH VHDVRQ $XJXVW DQG 6HSWHPEHU DUH SHDN PRQWKV IRU KXUULFDQH GHYHORSPHQW 12$$ D 2YHU D WZR\HDU SHULRG WKH 86 FRDVWOLQH LV VWUXFN E\ DQ DYHUDJH RI WKUHH KXUULFDQHV RQH RI ZKLFK LV FODVVLILHG DV D PDMRU KXUULFDQH +XUULFDQHV WURSLFDO VWRUPV DQG WURSLFDO GHSUHVVLRQV SRVH D WKUHDW WR OLIH DQG SURSHUW\ 7KHVH VWRUPV EULQJ KHDY\ UDLQ VWRUP VXUJH DQG IORRGLQJ 12$$ E )RU WKH SXUSRVH RI WKLV +03 DQG DV GHHPHG DSSURSULDWHG E\ WKH 'XWFKHVV &RXQW\ 6WHHULQJ DQG 3ODQQLQJ &RPPLWWHHV FRDVWDO KD]DUGV LQ WKH &RXQW\ LQFOXGH KXUULFDQHVWURSLFDO VWRUPV VWRUP VXUJH FRDVWDO HURVLRQ DQG 1RU (DVWHUV ZKLFK DUH GHILQHG EHORZ Hurricanes/Tropical Storms $ KXUULFDQH LV D WURSLFDO -

Current and Future Snow Avalanche Threats and Mitigation Measures in Canada

CURRENT AND FUTURE SNOW AVALANCHE THREATS AND MITIGATION MEASURES IN CANADA Prepared for: Public Safety Canada Prepared by: Cam Campbell, M.Sc.1 Laura Bakermans, M.Sc., P.Eng.2 Bruce Jamieson, Ph.D., P.Eng.3 Chris Stethem4 Date: 2 September 2007 1 Canadian Avalanche Centre, Box 2759, Revelstoke, B.C., Canada, V0E 2S0. Phone: (250) 837-2748. Fax: (250) 837-4624. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW. Calgary, AB, Canada, T2N 1N4, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Civil Engineering, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW. Calgary, AB, Canada, T2N 1N4, Canada. Phone: (403) 220-7479. Fax: (403) 282-7026. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Chris Stethem and Associates Ltd., 120 McNeill, Canmore, AB, Canada, T1W 2R8. Phone: (403) 678-2477. Fax: (403) 678-346. E-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents the results of the Public Safety Canada funded project to inventory current and predict future trends in avalanche threats and mitigation programs in Canada. The project also updated the Natural Resources Canada website and map of fatal avalanche incidents. Avalanches have been responsible for at least 702 fatalities in Canada since the earliest recorded incident in 1782. Sixty-one percent of these fatalities occurred in British Columbia, with 13% in Alberta, 11% in Quebec and 10% in Newfoundland and Labrador. The remainder occurred in Ontario, Nova Scotia and the Yukon, Northwest and Nunavut Territories. Fifty-three percent of the fatalities were people engaged in recreational activities, while 18% were people in or near buildings, 16% were travelling or working on transportation corridors and 8% were working in resource industries. -

Snowpack As Indicators of Atmospheric Pollution: the Valday Upland

atmosphere Article Snowpack as Indicators of Atmospheric Pollution: The Valday Upland Marina Dinu *, Tatyana Moiseenko * and Dmitry Baranov * Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, 119334 Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (D.B.) Received: 23 March 2020; Accepted: 1 May 2020; Published: 3 May 2020 Abstract: Snowpack is a unique indicator in assessing both local and transboundary contaminants. We considered the features of the snow chemical composition of the Valday Upland, Russia, as a location without a direct influence of smelters (conditional background) in 2016–2019. We identified the influence of a number of geochemical (landscape), biological (trees of the forest zone, vegetation), and anthropogenic factors (technogenic elements—lead, nickel) on the formation of snow composition. We found increases in the content of metals of technogenic origin in city snowfall in the snowpack: cadmium, lead, and nickel in comparison with snowfall in the forest. Methods of sequential and parallel membrane filtration (in situ) were used along with ion-exchange separation to determine metal speciation (labile, unlabile, inorganic speciation with low molecular weight, connection with organic ligands) and explain their migration ability. We found that forest snow samples contain metal compounds (Cu, Pb, and Ni) with different molecular weights due to the different contributions of organic substances. According to the results of filtration, the predominant speciation of metals in the urban snow samples is suspension emission (especially more 8 mkm). The buffer abilities of snowfall in the forest (in various landscapes) and in the city of Valday were assessed.