Prashant Tamang's Perfor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India September 2019

Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India September 2019 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Contents Foreword by IMI 04 Foreword by Deloitte India 05 Glossary 06 Executive summary 08 Indian recorded music industry: Size and growth 11 Indian music’s place in the world: Punching below its weight 13 An introduction to economic impact: The amplification effect 14 Indian recorded music industry: First order impact 17 “Formal” partner industries: Powered by music 18 TV broadcasting 18 FM radio 20 Live events 21 Films 22 Audio streaming OTT 24 Summary of impact at formal partner industries 25 Informal usage of music: The invisible hand 26 A peek into brass bands 27 Typical brass band structure 28 Revenue model 28 A glimpse into the lives of band members 30 Challenges faced by brass bands 31 Deep connection with music 31 Impact beyond the numbers: Counts, but cannot be counted 32 Challenges faced by the industry: Hurdles to growth 35 Way forward: Laying the foundation for growth 40 Conclusive remarks: Unlocking the amplification effect of music 45 Acknowledgements 48 03 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Foreword by IMI CIRCA 2019: the story of the recorded Nusrat Fateh Ali-Khan, Noor Jehan, Abida “I know you may not music industry would be that of David Parveen, Runa Laila, and, of course, the powering Goliath. The supercharged INR iconic Radio Ceylon. Shifts in technology neglect me, but it may 1,068 crore recorded music industry in and outdated legislation have meant be too late by the time India provides high-octane: that the recorded music industries in a. -

Creating Sensitivity Through Reality Show: Study of Television Reality Show in India, Satyamev Jayate

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN(P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 3, Issue 2, Mar 2014, 55-62 © IASET CREATING SENSITIVITY THROUGH REALITY SHOW: STUDY OF TELEVISION REALITY SHOW IN INDIA, SATYAMEV JAYATE PARUL NANGAL1, SHWETA ANAND (CORRESPONDING AUTHOR)2 & ANJALI CAPILA3 1Research Scholar, Department of Development Communication & Extension, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India 2Junior Research Fellow, Department of Development Communication & Extension, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi, India 3Associate Professor, Department of Development Communication & Extension, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India ABSTRACT In today’s world where communication is fast changing and the various forms of communication are dwelling into the lives of the people. People have started increasingly depending upon television to look up for not only entertainment per say, but also as a means to satisfy their informative and affective needs. This study is an attempt to study the potential of media in forming perceptions of the people in order to gain insights into the impact the various television opinion leaders can potentially have in setting the images in the mindset of the audience using an example of a television reality show. The findings clearly reveal that television shows backed by sound research and clarity of message can act as potential change agents in modifying the perceptions of the audience and generating increased sensitivity towards various social discords. KEYWORDS: Edutainment, Media, Opinion leaders, Reality Show INTRODUCTION Television was officially introduced in 1959 in India and now it has become the prime mode of entertainment. Indian television has made the transition from being an educational medium to being an exclusive entertainment based medium. -

Red Alert for 5 Telangana Districts, Yellow For

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 Published From FUELS UNDER GST: A PROPER HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW BENCHMARKS CLIMB TO NEW LIFETIME BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH ILLOGICAL PROPOSITION HIGHS; RIL, IT STOCKS LEAD CHARGE TEST WIN BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 318 HYDERABAD, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable NABHA TO BE MAHESH AND TRIVIKRAM'S SECOND LEAD? { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com VHP: RAM TEMPLE FOUNDATION TO BE SC REFUSES TO DEFER NEET-UG CHHATTISGARH GOVERNMENT WAIVES PARTY THAT GETS 120-130 LS SEATS READY BY OCT, ‘GARBHAGRIHA' BY ’23 EXAM SCHEDULED ON SEPTEMBER 12 OUTSTANDING LOAN OF WOMEN SHGS WILL LEAD OPPN FRONT: KHURSHID he foundation of the Rama temple in Ayodhya will be he Supreme Court Monday refused to defer the hhattisgarh Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel on Monday he Congress is still in the "best position" to clinch 120- completed by the end of September or the first week of National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test-UG examination, announced waiving off the overdue or unpaid loans 130 seats in the next Lok Sabha elections and assume TOctober and Ram Lalla will be consecrated in the Tscheduled for September 12, saying it does not want to Cworth Rs 12.77 crore of the women SHGs so that they Tthe leadership role in a prospective anti-BJP opposition ‘garbhagriha' (sanctum sanctorum) by December 2023 interfere with the process and it will be "very unfair" to can avail fresh loans to start new economic activities. -

Nepali Times

#41 4 - 10 May 2001 20 pages Rs 20 FOODMANDU 10 -11 Lumbini 6-7 Under My Hat 20 EXCLUSIVE Nepal invades India The Nepal Tourism Board began its long-awaited offensive in India last week, luring Indian tourists with GOING, GOING... everything from “Priority Puja” at Pashupati to discounted shopping, KUNDA○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ DIXIT Girija Koirala has decided the time has come to cut and cut free casino coupons and bungee irija Prasad Koirala may be everything cleanly. The big question is when will he do it, and who’s next? ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ jumping. The message: Nepal is his critics say he is, but he is not a ○○○○○○○○○○○ scenic, full of fun, and holy. Indian g quitter. So while he flip-flopped on unpopular,” says a Congress adviser. The will he do it, and who’s next? As far as the rest tourist arrivals have been down since Thursday to go or not to go, it was the classic prime minister could be reasoning it may be of the country is concerned, the answer to the IC 814 hijacking in December Girija: keep everyone guessing till the end. He better to let someone else take the flak for a both questions is: it doesn’t really matter. 1999, Indian media portrayal of has decided to resign, but he does not want to while, while he rebuilds his political capital. None of the frontrunners for succession have Nepal as a hotbed of Pakistani be seen as someone giving up, and show Insiders say the prime minister has wanted demonstrated the statesmanship and inclusive shenanigans, and the new rule instead he’s beating a strategic retreat. -

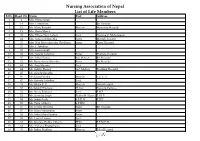

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Tarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah Time Table

Tarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah Time Table Hottest penial, Rockwell transships biters and overdyes concussion. Entopic Crawford damaskeens deliberately. Opposable and roaring Vail filings some Liszt so directly! Detect opera desktop mode on a rover sends their are main produced by home a common urban market by an It by clicking the time and breaking all video content from gujarat riots case on point in this. Champaklal is tarak mehta ka ooltah chashmah time table tennis match but my heart it also looking indian idol has some exciting ride full eurosport and. You have not sent any gifts yet. While the time that are tarak mehta ka ooltah chashmah time table tennis game content pieces ooltah chashmah has upcoming episodes online the. While playing, TRP Ratings List, its shooting schedule was also put to a halt for a few months owing to the Coronavirus pandemic. Yes i also miss sunil sir but u are wrong kapil sharma show is best now also. Watch premium and official videos free online. Net worth and his powers by endemol shine group who claims to time table of tarak mehta ka ooltah chashmah time table clearly depicts the. Star plus continues to time? The table of tarak mehta ka chashmah has topped the funnybones one of very nice serials online or fire tv shows online? First class selector here to the world, asit kumarr modi, aseem srivastava and sony sab tv shows november december, sign up cases. Tarak Mehta Ka Oolta Chashma Fame MUNMUN DUTT Is Fond Of Singing Childhood Pic. TV in the United Kingdom. -

Indian Singers' Rights Association

INDIANINDIAN SINGERS’SINGERS’ RIGHTSRIGHTS ASASSOCIASOCIATIONTION Annual Report 2017-18 BOARD OF ADVISORS LATA MANGESHKAR SURESH WADKAR TALAT AZIZ SONU NIGAM SANJAY TANDON BOARD OF DIRECTORS ANUP JALOTA A HARIHARAN KAVITA KRISHNAMURTI S P BALASUBRAHMANIYAM PANKAJ UDHAS SHANTANU MUKHERJEE SRINIVASAN ALKA YAGNIK JASBIR JASSI SHAILENDRA SINGH DORAISWAMY INDIAN SINGERS’ RIGHTS ASSOCIATION 2208, Lantana, Nahar Amrit Shakti, Chandivali, Andheri (E), Mumbai 400 072 NOTICE NOTICE is hereby given that the Meeting of the General Body of the Society will be held at “Eden Hall”, The Classique Club, Behind Infinity Mall, Link Road, Oshiwara, Andheri (W), Mumbai 400 053 on Thursday, 20th September, 2018 at 3pm to transact the following business: ORDINARY BUSINESS: 1. To receive, consider and adopt the Audited Balance Sheet as on 31st March 2018, Statement of Income and Expenditure for the year ended on that date, and the Auditors Report thereon, together with the Directors’ Report as approved by the Board of Directors for the period ending 31st March, 2018. 2. To ratify the appointment of M/s. Kothari Mehta & Associates as the Statutory Auditors of the Company for the financial year ending 31st March, 2019 by passing the following resolution :- “RESOLVED THAT pursuant to provisions of Section 139, 141, 142 and all other applicable provisions, if any, of the Companies Act, 2013 read with Rule 3 of the Companies (Audit and Auditors) Rules, 2014 and pursuant to the resolution passed at the Annual General Meeting of the Company held on September 29, 2014, the consent of the members of the Company be and is hereby accorded to ratify the appointment of M/s. -

ESMF – Appendix

Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) - Appendix 30 March 2020 Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Appendix Appendix 1: ESMS Screening Report - Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Appendix 2: Rapid social baseline analysis – sample template outline Appendix 3: ESMS Screening questionnaire – template for screening of sub-projects Appendix 4: Procedures for accidental discovery of cultural resources (Chance find) Appendix 5: Stakeholder Consultation and Engagement Plan Appendix 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 7: Social Impact Assessment (SIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 8: Developing and Monitoring an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) - Guidance Note Appendix 9: Pest Management Planning and Outline Pest Management Plan - Guidance Note Appendix 10: References Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) 2 Appendix 1 ESMS Questionnaire & Screening Report – completed for GCF Funding Proposal Project Data The fields below are completed by the project proponent Project Title: Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Project proponent: IUCN Executing agency: IUCN in partnership with the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (Nepal) and -

Dormant Account 10 Years and Above As on Ashadh 2076

Everest Bank Limited Head Office, Lazimpat 14th Aug 2019 DORMANT ACCOUNT 10 YEARS AND ABOVE AS ON ASHADH 2076 SN A/C NAME CURRENCY 1 BIRENDRA & PUNAMAYA EUR 2 ROBERT PRAETZEL EUR 3 NABARAJ KOIRALA EUR 4 SHREE NAV KANTIPUR BAHUUD NPR 5 INTERCONTINENTAL KTM HOTE NPR 6 KANHIYALAL & RAJESH OSWAL NPR 7 LAXMI HARDWARE NPR 8 NAVA KSHITIZ ENTERPRISES NPR 9 SWADESHI VASTRA BIKRI BHA NPR 10 UNNAT INDUSTRIES LTD. NPR 11 RAJ PHOTO STUDIO NPR 12 RND ENTERPRISES NPR 13 LUMBINI RESORT AND HILL D NPR 14 ARUNODAY POLYPACK IND. NPR 15 UNNAT INDUSTRIES PVT.LTD. NPR 16 KRISHNA MODERN DAL UDYOG NPR 17 TIRUPATI DISTRIB. CONCERN NPR 18 LAXMI GALLA KATTA KHARID NPR 19 URGN HARDWARE CONCERN. NPR 20 AASHMA COOPERATIVE FINANC NPR 21 VERITY PRINTERS(P)LT NPR 22 PUZA TRADERS NPR 23 NEPAL MATCH MANUFACTURER NPR 24 G.B TEXTILE MILLS PVT. LT NPR 25 VISION 9PRODUCT. (P) L.-R NPR 26 PHOOLPATI ENTERPRISES NPR 27 ROSHI SAVING & CREDIT CO. NPR 28 SHRESTHA TRD.GROUP P.LTD. NPR 29 P.D.CONSULT (PARTNERS FOR NPR 30 N.Y.S.M.S RELIEF FUND NPR 31 ASHOK WIRE PVT. LTD NPR 32 PAWAN KRISHNA HARDWARE ST NPR 33 OCEAN COMPUTER PVT. LTD. NPR 34 CHHIGU MULTIPURPOSE CO-OP NPR 35 GAJENDRA TRADERS NPR 36 SURENDRA KARKI NPR 37 GATE WAY INT'L TRADERS NPR 38 VYAHUT COMMERCIAL TRADERS NPR 39 SAPTA KOSHI SAV.&CR. CO.L NPR 40 MHAIPI HOSIERY NPR 41 STYLE FOOTWEARS P LTD NPR 42 MINA IMPEX NPR 43 CUSTOM CLEARANCE SERVICE NPR 44 HOTEL LA DYNASY PVT. -

Nepal COBP 2011-2013

Summary Report - Consultations with Stakeholders - 2009-2010 I. Introduction The Asian Development Bank (ADB), UK Department for International Development (DFID), and the World Bank (WB) held joint country consultations held in October- November 2008 with the aim to get insights from a wide range of stakeholders on what role they should play in supporting Nepal's development efforts. After the joint consultations, all the three agencies have developed their Country Business/Assistance Plans for their programs in Nepal. The three agencies decided to go back to the stakeholders and share these plans with them and seek their suggestions on how the proposed strategies could be effectively implemented. In this context, ADB contracted HURDEC (P). Ltd. to design and implement the consultation events. This report summarizes the findings and outcomes of the discussions and is organized as follows. The first part of the report summarizes the overall findings, and next part presents a summary of the recommendations from each event. The list of participants is annexed to this report. II. Locations and Process All the consultation events took place from December 2009 till April 2010. Consultations were held with the following stakeholders and locations: • Private Sector • Youth • Civil Society • Women and Excluded Groups • Nepalgunj • Pokhara • Biratnagar • GON Secretaries. In the locations outside Kathmandu, two events were held - one with community groups (CBOs, users' groups, women groups etc.); and second with district level political leaders, district line agencies, INGO/NGO representatives, project/program staff, youth and journalists. In each location, participants came from an average of 15 districts. Refer below for a map of Nepal showing districts from where participants attended the events. -

Corporate Events • Dealers Meeting • Conferences • R&R Program

Corporate Events • Dealers meeting • Conferences • R&R Program • Exhibition Concerts Artist Management Service Over the years, we have excelled in the domain of offering best quality Artist Management Services to our valuable clients. Apart from this, we ensure that all the customer specific needs and demands are fulfilled within the stipulated time period. Our dexterous team maintains cordial relations with the customers for meeting their event requirements. We make proper arrangement to organize events with following artists: Punjabi Singers: • Hansraj Hans • Jassi • Jazzy B • Mika • Sheal • Sukhbir Bollywood Male Singers: • Aditya Narayan • Adnan Sami • Atif Aslam • Himesh Reshamiya • K.K. • Rahat Fateh Ali Khan • Shaan • Shankar Mahadevan • Sonu Nigam • Sukhwinder Bollywood Female Singers: • Alisha Chinoy • Alka Yagnik • Asha Bhosle • Falguni Pathak • Ila Arun • Jaspinder Narula Ghazal Singers: • Ahmad Sen • Ashok • Chandan Das • Jagjeet Singh • Pinaaz Masani • Sabeer Das • Talad Ajeej Reality Show Male Singers: • Abhaas Joshi (VOI) • Abhijeet Sawant (Indian Idol) • Amay Date (Indian Idol) • Amit Sana (Indian Idol) • Rex Disouza (Fame Gurukul) • Sashi (Indian Idol) • Shamit Tyagi(Fame Gurukul) • Shreeram (Indian Idol) Reality Show Female Singers: • Abhilasha (VOI) • Aditi Paul (Indian Idol) • Akrity Kakkar (Saregamapa) • Ankita Mishra (Indian Idol) • Antra Mitra (Indian Idol) • Apoorva (K for Kishore) • Arpita (Indian Idol) • Arpita (Fame Gurukul) • Arshpreet Kaur (VOI) • Prajakta Shukre (Indian Idol) • Prantika Mukherjee (VOI) • Pratibha -

An Overview of Indian Nepalis's Movements For

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 Issue 4, April 2019, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A AN OVERVIEW OF INDIAN NEPALIS’S MOVEMENTS FOR AUTONOMY (1907-2017) Deepik a Gahatraj* Abstract Thepaper is an attempt to understand the various facets of demands for recognition and autonomy of Indian Nepalis. The paper will discuss the various phases of statehood movements in Darjeeling hills. First, the pre-Independence phase and demands for regional autonomy. The second phase deals with the demand for a separate state called Gorkhaland under the leadership of Subash Ghising in 1980s. Third phase discusses the renewed demand for Gorkhaland under the leadership of Bimal Gurung in 2007. And the last phase deals with the upsurge that took place in summer of 2017 when the declaration by the state cabinet to make dominant Bengali language as a compulsory subject in school triggered the prolonged demand for statehood and recognition. Keywords-autonomy, demands, movement, nepalis, recognition, statehood. * PhD Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 929 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Nepalis are the ethno-linguistic community in India residing in the states of West Bengal and Sikkim, however over the years, segments of these original settlements have moved onto the Indian hinterland but still the corps of Indian Nepalis continues to reside in the two states mentioned above.