The Philippines 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tropical Depression USMAN and the Heavy Rainfall Event of 28-29 December 2018

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) Weather Division TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT Tropical Depression USMAN and the Heavy Rainfall Event of 28-29 December 2018 st Tropical Depression USMAN is the 21 and last Philippine tropical cyclone for the 2018 season and only tropical cyclone within the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) for the month of December 2018. As a tropical depression during its entire lifespan, USMAN did not bear any international name from the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RSMC) in Tokyo. Although relatively weak by meteorological standards, this tropical depression was one of the key weather systems that caused the Heavy Rainfall Event of 28-29 December 2018 over large portions of Southern Luzon and Eastern Visayas that resulted in hundreds of casualties and millions of pesos in damages to personal and public property. Meteorological History USMAN developed from a tropical disturbance embedded within a near-equatorial buffer zone (Conover and Sadler 1960; Ramage 1995) situated over the western portion of the Caroline Islands. This disturbance was first noted on the surface weather chart in the afternoon of 23 December 2018. PAGASA first noted the disturbance as a tropical depression at 2:00 PM of 25 December with maximum winds of 45 km/h and central pressure of 1002 hPa as the system approached Palau. USMAN entered the PAR at 3:00 PM of the same day. (a) (b) Fig. 1. (a) Himawari-8 RGB composite image at 2:00 PM on 28 December and (b) DOST-PAGASA warning best track of Tropical Depression USMAN. -

OFFICIALS SCHOOLS L(Cpur)Ltc (Jr Rllri I-Fliilpprirb$ 'Fi3$F# Department of Educati Ps.Frhn

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education National Capital Region DIVISION OF CITY SCHOOLS Quezon City SFHS Comp., Nueva Ecija St., Bantay, Quezon City r 21,2011 Division Memorandum No. .'&E s. 2Afi SYNCHRONIZING WTH THE PHILIPPINE ST, TIME To: Asst. Schools Division Superintenden Divi sion/District $upervisors/Coordi Elementary/Secondary School Princi Head Teachers/Officers ln-Charge Chief Administrative Officer Heads, Administrative Units For the information and guidance of ail d, enclosed is DepEd Order No. 86, s, 2A11 from Br. ARMIN A. LUIS RO FSC, Secretary, Department of Education, Meralco Avenue, Pasig Ci , dated November 3, 2011, on the subject: SyTVCHRONIZING WITH THE LIPPINE STANDARD TIME, which is self-explanaiory. lmmediate and wide dissemination of this Memo ndum is desired CORAZON C. RUBI , cEso vt $chools Division Su rintendent Reference: None To be indicated in the Perpetual lndex under the following subjects: BUREAUS AND OFFICES POLICY OFFICIALS SCHOOLS l(CpUr)ltc (Jr rllri I-flIilpprirb$ 'fi3$F# Department of Educati Ps.frHn 0 3 ?011 DepEdORDER No.$$, s. 2O1l SYNCHRONIZING W:ITH THE PIIEIPPINE ST To: Undersecretaries Assistant Secretari.es Bureau Directors Directors of Services, Centers, and Heads of Units Regional Directors Schools Division/City Superintendents !-i Fleads, Public Elementary Schools A11 Others Concerrred t. To s5mchronize al7 activities of the Department of Edu {DepEd) from the Central Ofhce to the school level, all DepEd Offices are here directed to set all clocks inside offices and school properties including time ing devices (a1so known as bundy clocks, clock card machines, or punch c to match the Philippine Standard Time (PST) established by the Departme t of Science and Technologr {DOST) through the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysicerl and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). -

Geri Sell Pgold Buy

Trading Guide Philstocks Research JUSTINO B. CALAYCAY, JR Date : October 7 – October 14, 2019 AVP-Head, Research & Engagement (632)588-1962 JAPHET LOUIS O. TANTIANGCO GERI SELL Sr. Research Analyst (632)588-1927 Last Traded Price 1.18 Sentiment towards POGO crackdown PIPER CHAUCER E. TAN Entry Point - Engagement Officer/Research Associate Technicals indicate investors (632)588-1928 Target Price 1.00 negative sentiments on GERI Potential Upside / Downside -15.25% CLAIRE T. ALVIAR Investors should avoid this stock. It Research Associate Net Foreign Position* Php 1.56M may rebound at its psychological (632)588-1925 52 wk High and Low 0.96 - 1.63 support given the behavior of the Ground Floor, East Tower 20 MA Volume 599.25K stock PSE Center, Tektite Towers * YTD as of October 4, 2019 Ortigas Center, Pasig City P/E Ratio 8.38 PHILIPPINES P/B Ratio 0.485 DISCLAIMER YTD performance 4.42% The opinion, views and recommendations contained in this material were prepared by the Philstocks Research Team, individually and separately, based on their specific PGOLD BUY sector assignments, contextual framework, personal judgments, biases and prejudices, Last Traded Price 38.50 time horizons, methods and other factors. Slower inflation would benefit the The reader is enjoined to take this into Entry Point 36.00 account when perusing and considering the business. contents of the report as a basis for their Target Price 48.55 stock investment or trading decisions. Potential Upside / Downside 35% RSI (14) is at oversold level. Furthermore, projection made and presented in this report may change or be updated in Net Foreign Position* Php302 million P/E ratio is at 17.14, lower than its between the periods of release. -

Trading Guide Philstocks Research JUSTINO B

Trading Guide Philstocks Research JUSTINO B. CALAYCAY, JR Date : June 29 - July 10, 2020 VP-Head, Research & Traditional Sales +63 (2) 8588-1962 NOW JAPHET LOUIS O. TANTIANGCO Sr. Research Analyst TRADE TP: Php 2.35 +63 (2) 8588-1927 PIPER CHAUCER E. TAN Engagement Officer/Research Associate +63 (2) 8588-1928 KEY MARKET STATS CLAIRE T. ALVIAR Last Traded Price (PHP) 2.06 Research Associate Source: Philstocks Research , PSE +63 (2) 8588-1925 Entry Point (PHP) 2.00 - 2.10 Cutloss Price (PHP) 5% below entry Key Investment Highlights Ground Floor, East Tower PSE Center, Tektite Towers Aims to deploy 5G Fixed Wireless Access network in Potential Upside / Downside (%) 17.50 - 11.90 Ortigas Center, Pasig City NCR and nearby areas over 5 years. 52 wk low and High (PHP) 1.00 - 4.78 PHILIPPINES Businesses’ digitization plans offer opportunities. 20 MA Volume 8.19 M Share price is currently forming a triangle pattern. DISCLAIMER P/E Ratio (x) 438.30 The opinion, views and recommendations P/B Ratio (x) 1.76 YTD Net Foreign Transaction (as of June 26, 2020): contained in this material were prepared by YTD performance (%) -17.27% Php2.85 M the Philstocks Research Team, individually and separately, based on their specific sector assignments, contextual framework, HOME personal judgments, biases and prejudices, time horizons, methods and other factors. BUY TP: Php 9.45 The reader is enjoined to take this into account when perusing and considering the contents of the report as a basis for their stock investment or trading decisions. Furthermore, projection made and presented KEY MARKET STATS in this report may change or be updated in Last Traded Price (PHP) 7.27 between the periods of release. -

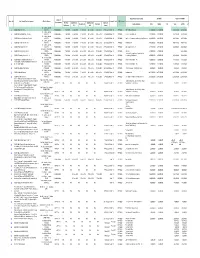

CY2020 PMR.Xlsx

a Actual Procurement Activity ABC (PhP) Contract Cost (PhP) Mode of Reso. No. Title / Item(s) for Procurement Office / End‐user Source of Funds APP Inclusion Procurement Pre‐Proc Ads/Post of Sub/Open of Notice of Pre‐bid Conf Post Qual Notice of Award Total MOOE CO Total MOOE CO Conference IAEB Bids Award Mr. Dante L. Lontok 1 CY2020 Shuttle Services AS-GSD Public Bidding 17-Oct-2019 31-Oct-2019 7-Nov-2019 20-Nov-2019 4-Dec-2019 27-Dec-2019 Fund 101 APP 2020 MG Pacific Trans Corp 13,100,000.00 13,100,000.00 12,735,282.00 12,735,282.00 Mr. Dante L. Lontok 2 CY2020 Aircon Maintenance Services AS-GSD Public Bidding 11-Oct-2019 31-Oct-2019 7-Nov-2019 20-Nov-2019 11-Dec-2019 6-Feb-2020 Fund 101 APP 2020 Rose Aire Enterprise Inc 1,973,000.00 1,973,000.00 1,637,198.40 1,637,198.40 Mr. Dante L. Lontok 3 CY2020 Electrical Maintenance Services AS-GSD Public Bidding 11-Oct-2019 31-Oct-2019 7-Nov-2019 20-Nov-2019 5-Dec-2019 6-Feb-2020 Fund 101 APP 2020 Azulerem Construction and Engineering Services 4,248,000.00 4,248,000.00 4,207,969.64 4,207,969.64 Mr. Dante L. Lontok 5 CY2020 Specialty Trade Services AS-GSD Public Bidding 11-Oct-2019 31-Oct-2019 7-Nov-2019 20-Nov-2019 10-Dec-2019 29-Jan-2020 Fund 101 APP 2020 Omniworx, Inc 4,436,000.00 4,436,000.00 4,424,831.52 4,424,831.52 Mr. -

Philippine Distribution Code 2016 Edition, with the Following Salient Features

PHILIPPINEPHILIPPINE DISTRIBUTION DISTRIBUTION CODE CODE 2014 201EDITION6 EDITION November 2016 iv FOREWORD As the Philippine economy continues to grow, the demand for sufficient, stable, safe and reliable supply of electricity by business industries and households steadily increases. It is imperative that as the country expands its power generation capacity both in terms of renewable and non-renewable energy sources, the development, operation and maintenance of electric power distribution facilities meet the technical standards, rules and regulations to ensure a safe, reliable and efficient Distribution System in the country. The Philippine Distribution Code (PDC) 2016 Edition is the result of several years of technical review, analysis, and coordination work among the members and technical staff of the Distribution Management Committee, Inc. (DMC), in close collaboration with the stakeholders of the power distribution sector and guidance of the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC). In the exercise of its mandate “to initiate and coordinate revisions of the Philippine Distribution Code and make recommendations to the Energy Regulatory Commission” (Section 2.2.1 (e), PDC 2001), the Distribution Management Committee, Inc. (DMC) initiated the review of the PDC in 2010 and invited Users of the Distribution System to propose amendments to the PDC. A thorough evaluation by the DMC and expository hearings and public consultations with stakeholders were then conducted in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. Moreover, with a vision of establishing an up-to-date set of national technical standards and guidelines that will serve as national code for Users of the Distribution System, the PDC 2016 Edition has taken into account the adoption in the Philippines of new and emerging technologies including Variable Renewable Energy (VRE), as well as best practices and experiences of foreign jurisdictions in the use of these technologies. -

The Prospectus Is Being Displayed in the Website to Make the Prospectus Accessible to More Investors. the Pse Assumes No Respons

THE PROSPECTUS IS BEING DISPLAYED IN THE WEBSITE TO MAKE THE PROSPECTUS ACCESSIBLE TO MORE INVESTORS. THE PSE ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CORRECTNESS OF ANY OF THE STATEMENTS MADE OR OPINIONS OR REPORTS EXPRESSED IN THE PROSPECTUS. FURTHERMORE, THE STOCK EXCHANGE MAKES NO REPRESENTATION AS TO THE COMPLETENESS OF THE PROSPECTUS AND DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY WHATSOEVER FOR ANY LOSS ARISING FROM OR IN RELIANCE IN WHOLE OR IN PART ON THE CONTENTS OF THE PROSPECTUS. ERRATUM Page 51 After giving effect to the sale of the Offer Shares and PDRs under the Primary PDR Offer (at an Offer price of=8.50 P per Offer Share and per PDR) without giving effect to the Company’s ESOP, after deducting estimated discounts, commissions, estimated fees and expenses of the Combined Offer, the net tangible book value per Share will be=1.31 P per Offer Share. GMA Network, Inc. GMA Holdings, Inc. Primary Share Offer on behalf of the Company of 91,346,000 Common Shares at a Share Offer Price of=8.50 P per share PDR Offer on behalf of the Company of 91,346,000 PDRs relating to 91,346,000 Common Shares and PDR Offer on behalf of the Selling Shareholders of 730,769,000 PDRs relating to 730,769,000 Common Shares at a PDR Offer Price of=8.50 P per PDR to be listed and traded on the First Board of The Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Sole Global Coordinator, Bookrunner Joint Lead Manager, Domestic Lead Underwriter and Lead Manager and Issue Manager Participating Underwriters BDO Capital & Investment Corporation First Metro Investment Corporation Unicapital Incorporated Abacus Capital & Investment Corporation Pentacapital Investment Corporation Asian Alliance Investment Corporation RCBC Capital Corporation UnionBank of the Philippines Domestic Selling Agents The Trading Participants of the Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. -

CCBO-APS Philippines Updated Questions and Answers

CLEAN CITIES, BLUE OCEAN Annual Program Statement – Questions and Answers Opportunity Number: CCBO-APS-Philippines-001 Download APS https://urban-links.org/project/ccbo/ Phase 1: Concept Papers Issuance Date: February 26, 2020 Deadlines for Concept 6pm Philippine Standard Time on the following dates: Papers: March 20, April 30, July 30, September 25, December 4, 2020; February 5, 2021 Questions: [email protected] Questions will be compiled at the end of each week and answers will be posted on the Urban Links website above. April 20, 2020 Question 1 If participants were declined from the 2nd round, are there any limitations of submission of entries for the concept paper in future rounds? Answer 1 If applicants submit an unsuccessful concept paper, the organization may apply again in future rounds. Question 2 Should there be a minimum requirement of members of an organization? Are there other requirements for a particular organization to be eligible? If (one) participant were to be a new member of a non-government organization, are there violations for this? Answer 2 There are no requirements on the number of members of an organization or the period of time members have been employed by an organization. The entity must be registered as an organization, company or other group (grants may not be given to individuals). Additional eligibility information can be found in Section 3 of the APS. Question 3 If a participant was not from any of the "Pilot Sites" but eligible, proven that the location consists of some marine debris, should there be other supporting documents to be prepared? CCBO-APS-Philippines-001 Question and Answer 1 Answer 3 Applying organizations do not have to be from or working in the Pilot Sites, but their understanding of the local context will be evaluated in the Concept Paper. -

DVD Piracy As Alternative Media: the Scandal of Piracy, and the Piracy of “Scandal” in the Philippines, 2005–2009

MARIA F. MANGAHAS 109 Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies 2014 29 (1): 109–139 DVD Piracy as Alternative Media: The Scandal of Piracy, and the Piracy of “Scandal” in the Philippines, 2005–2009 MARIA F. MANGAHAS ABSTRACT. Some digital materials which are documentary of specific forms of social transgression comprise an apparent “market niche” for piracy. “Scandals” as unique commodities in the Philippines’s informal market for pirated disks are quite distinct from other digital entertainment, being originally candid/unstaged or “stolen”/taken without their subject’s knowledge and usually made to non-professional standards/ equipment. Enterprisingly put on the market by pirate-entrepreneurs because of apparent consumer-audience interest in the content, such unique “reality” goods became conveniently available through networks of digital piracy outlets. In the context of consumption of pirated goods, the article reads “scandals” as expressive of everyday critique and resistance. The niche market for “scandals” functions as alternative media as these digital goods inherently evade government and (formal) corporate control as sources of news and entertainment. Indicators of the significance of “scandal” in the informal economy and the meaningful convergence between its piracy and consumer- audience demand are examined ethnographically: their translation into commodities through packaging, the range of sites for consumers to access “scandals,” pirate- entrepreneurs’ sales strategies and standards, and how the market behavior of these “scandals” apparently responded to the unfolding of the social scandals in real time as current events—events that themselves were influenced by the popular circulation and piracy of these commodities. Three cases that took place between 2005–2009—“Hello Garci,” the “Kat/Kho sex scandals,” and the “Maguindanao massacre” DVD—serve as diverse examples, each with their own issues of authenticity, morality, and social effects consequent to piracy and consumption. -

Cross-Border Issues for Digital Platforms: a Review of Regulations Applicable to Philippine Digital Platforms

DECEMBER 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2020-45 Cross-Border Issues for Digital Platforms: A Review of Regulations Applicable to Philippine Digital Platforms Aiken Larisa O. Serzo The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. CONTACT US: RESEARCH INFORMATION DEPARTMENT Philippine Institute for Development Studies [email protected] 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris - North Tower https://www.pids.gov.ph EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines (+632) 8877-4000 Cross-Border Issues for Digital Platforms: A Review of Regulations Applicable to Philippine Digital Platforms Aiken Larisa O. Serzo PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES December 2020 Abstract This Paper identifies certain policy issues in the existing regulatory infrastructure of the Philippines which may prevent digital platforms in the Philippines from innovating and participating in the global digital economy. In brief, these policy issues relate to the incoherence between the national innovation strategy of the government and the mishmash of regulations that digital platforms are subjected to. In particular, this relates to investment regulations, regulations on mass media, retail, advertising, logistics, telecommunications, and education. Such landscape has led to a regulatory environment that is unable to provide certainty as to the legality of the activities of Philippine- based digital platforms. -

Definitive Information Statement

C O V E R S H E E T A 1 9 9 6 0 0 1 7 9 C O M P A N Y N A M E N O W C O R P O R A T I O N PRINCIPAL OFFICE (No. / Street / Barangay / City / Town / Province) U N I T 5 - I , 5 T H F L O O R , O P L B U I L D I N G , 1 0 0 C . P A L A N C A S T R E E T , L E G A S P I V I L L A G E , M A K A T I C I T Y Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If Form Type report Applicable 2 0 - IS S E C N / A C O M P A N Y I N F O R M A T I O N Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number (632)750-0461 N/A [email protected] (632) 750-0211 Annual Meeting No. of Stockholders (Month / Day) Fiscal Year (Month / Day) 70 First Thursday of June 12/31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Angeline L. Macasaet angeline.macasaet@now- (632) 750-0211 N/A corp.com CONTACT PERSON’s ADDRESS Unit 5-I, 5th Floor, OPL Building 100 C. Palanca Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City NOTE 1 : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT ..............................................................................................................................