Rhode Island Rivers Policy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Corridor Plan for the Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed, RI and CT

River Corridor Plan for the Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed, RI and CT Prepared for Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association Hope Valley, RI Prepared by John Field Field Geology Services Farmington, ME June 2016 Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed River Corridor Plan - June 2016 Page 2 of 122 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 FLUVIAL GEOMORPHOLOGY AND ITS VALUE IN CORRIDOR PLANNING ............ 6 3.0 CAUSAL FACTORS OF CHANNEL INSTABILITIES ........................................................ 7 3.1 Hydrologic regime stressors ................................................................................................. 8 3.2 Sediment regime stressors..................................................................................................... 9 4.0 DELINEATING REACHES UNDERGOING OR SENSITIVE TO ADJUSTMENTS ....... 10 4.1 Constraints to sediment transport and attenuation .............................................................. 10 4.1a Alterations in sediment regime ..................................................................................... 11 4.1b Slope modifiers and boundary conditions..................................................................... 12 4.2 Sensitivity analysis............................................................................................................. -

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 Pages, February, 1990

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 pages, February, 1990. 1991-2000: Governor Bruce Sundlun inaugurated January 1, 1991. General Assembly created RI Rivers Council (RC) – RI General Law 46-28. Kenneth Payne became RC chair. Statewide Planning Program provides staff support to RC. RC concluded in 1992 that "more effective integration of existing programs and authority for rivers is needed." RC formulated draft classifications for rivers in 1993. RC held four workshops in northern, central, southern and eastern RI in 1994 to refine draft river classifications. Governor Lincoln Almond inaugurated January 1, 1995. Michael Cassidy, Planner for the City of Pawtucket, became RC chair. RC, working with the Divison of Planning, created digital maps of the state's watersheds. The State Planning Council adopted the RI Rivers Policy and Classification Plan, in January 1998, as State Guide Plan Element 162. RC established policies for recognizing local watershed councils in 1998. The Blackstone, Saugatucket and Wood-Pawcatuck were first river systems to have watershed councils designated by RC. Note: Designated watershed councils have certain legal authority and standing to represent their water bodies in state and local jurisdictions as well as be eligible for state grants via RC. 2001-2007: Meg Kerr became RC chair. General Assembly commences in 2001 providing annual legislative grants to RC from $22,000 to $52,000 range. Annual grant rounds commence from RC to designated local watershed councils generally in $2,500 to $7,500 range from Fiscal Year 2002 to the present. -

J. Matthew Bellisle, P.E. Senior Vice President

J. Matthew Bellisle, P.E. Senior Vice President RELEVANT EXPERIENCE Mr. Bellisle possesses more than 20 years of experience working on a variety of geotechnical, foundation, civil, and dam engineering projects. He has acted as principal-in-charge, project manager, and project engineer for assignments involving geotechnical design, site investigations, testing, instrumentation, and construction monitoring. His experience also includes over 500 Phase I inspections and Phase II design services for earthen and concrete dams. REGISTRATIONS AND Relevant project experience includes: CERTIFICATIONS His experience includes value engineering of alternate foundation systems, Professional Engineer – Massachusetts, ground improvement methodologies, and temporary construction support. Mr. Rhode Island, Bellisle has also developed environmental permit applications and presented at New Hampshire, New York public hearings in support of public and private projects. Dam Engineering PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS): Principal-in- American Society of Civil Charge/Project Manager for various stability analyses and reports to assess Engineers long-term performance of vegetated emergency spillways. Association of State Dam - Hop Brook Floodwater Retarding Dam – Emergency Spillway Safety Officials Evaluation - George H. Nichols Multipurpose Dam – Conceptual Design of an Armored Spillway EDUCATION - Lester G. Ross Floodwater Retarding Dam – Emergency Spillway University of Rhode Island: Evaluation M.S., Civil Engineering 2001 - Cold Harbor Floodwater Retarding Dam – Emergency Spillway B.S., Civil & Environmental Evaluation Engineering, 1992 - Delaney Complex Dams – Emergency Spillway Evaluation PUBLICATIONS AND Hobbs Pond Dam: Principal-in-Charge/Project Manager for the design PRESENTATIONS and development of construction documents of a new armored auxiliary spillway and new primary spillway to repair a filed embankment and Bellisle, J.M., Chopy, D, increase discharge capacity. -

Thames River Basin Partnership Partners in Action Quarterly Report

Thames River Basin Partnership Partners in Action Quarterly Report Summer 2018 Volume 47 The Thames River watershed includes the Five Mile, French, Moosup, Natchaug, Pachaug, Quinebaug, Shetucket, Willimantic, and Yantic Rivers and all their tributaries. We’re not just the "Thames main stem." Greetings from the Thames River Basin Partnership. Once again this quarter our partners have proven their ability to work cooperatively on projects compatible with the TRBP Workplan and in support of our common mission statement to share organizational resources and to develop a regional approach to natural resource protection. I hope you enjoy reading about these activities as much as I enjoy sharing information about them with you. For more information on any of these updates, just click on the blue website hyperlinks in this e-publication, but be sure to come back to finish reading the rest of the report. Jean Pillo, Watershed Conservation Project Manager Eastern Connecticut Conservation District And TRBP Coordinator Special Presentation If you missed the July 2018 meeting of the Thames River Basin Partnership, then you missed a presentation by Chuck Toal, Avalonia Land Conservancy’s development and programs director. Chuck gave a presentation on the 50 years of accomplishments of ALC as a regional land trust. ALC is focused on 22 towns in southeastern Connecticut. ALC, which oversees 4000 acres of preserved land, achieved accreditation in 2017. Their success has resulted from a working board of directors and the establishment of town committees to focus on smaller areas. Their current focus is to be more selective on land acquisition, particularly concentrating on building blocks of open space while also building an endowment fund land stewardship going forward. -

Views of the Blackstone River and the Mumford River

THE SHlNER~ AND ITS USE AS A SOURCE OF INCOME IN WORCESTER, AND SOUTHEASTERN WORCESTER COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS By Robert William Spayne S.B., State Teachers College at Worcester, Massachusetts 19,3 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Oberlin College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Geography CONTENTS Ie INTRODUCTION Location of Thesis Area 1 Purpose of Study 1 Methods of Study 1 Acknowledgments 2 II. GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHERN WORCESTER COUNTY 4 PIiYSICAL GEOGRAPHY 4 Topography 4 stream Systems 8 Ponds 11 Artificial 11 Glacial 12 Ponds for Bait Fishing 14 .1 oJ Game Fishing Ponds 15 Climatic Characteristics 16 Weather 18 POPULATION 20 Size of Population 20 Distribution of Population 21 Industrialization 22 III. GEOGRAPHICAL BASIS FOR TEE SHINER INDUSTRY 26 Recreational Demands 26 Game Fish Resources 26 l~umber of ;Ponds 28 Number of Fishermerf .. 29 Demand for Bait 30 l IV. GENERAL NATURE OF THE BAIT INDUSTRY 31 ,~ Number of Bait Fishermen 31 .1 Range in Size of Operations 32 Nature of Typical Operations 34 Personality of the Bait Fishermen 34 V. THE SHINER - ITS DESCRIPTION, HABITS AND , CHARACTERISTICS 35 VI. 'STANDARD AND IlIIlPROVISED EQUIPMENT USED IN .~ THE IhllUSTRY 41 Transportation 41 Keeping the Bait Alive 43 Foul Weather Gear 47 Types of Nets 48 SUCCESSFUL METHODS USED IN NETTING BAIT 52 Open Water Fishing 5'2 " Ice Fishing 56 .-:-) VII. ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE SHINER INDUSTRY ~O VIII. FUTURE OUTLOOK FOR THE SHINER INDUSTRY 62 IX. BIBLIOGRAPHY 69 x. APPENDIX 72 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Following Page . -

NASCO Rivers Database Report by Jurisdiction

NASCO Rivers Database Report By Jurisdiction Photos courtesy of: Lars Petter Hansen, Peter Hutchinson, Sergey Prusov and Gerald Chaput Printed: 17 Jan 2018 - 16:24 Jurisdiction: Canada Region/Province: Labrador Conservation Requirements (# fish) Catchment Length Flow Latitude Longitude Category Area (km2) (km) (m3/s) Total 1SW MSW Adlatok (Ugjoktok and Adlatok Bay) 550218 604120 W N Not Threatened With Loss 4952 River Adlavik Brook 545235 585811 W U Unknown 73 Aerial Pond Brook 542811 573415 W U Unknown Alexis River 523605 563140 W N Not Threatened With Loss 611 0.4808 Alkami Brook 545853 593401 W U Unknown Barge Bay Brook 514835 561242 W U Unknown Barry Barns Brook 520124 555641 W U Unknown Beaver Brook 544712 594742 W U Unknown Beaver River 534409 605640 W U Unknown 853 Berry Brook 540423 581210 W U Unknown Big Bight Brook 545937 590133 W U Unknown Big Brook 535502 571325 W U Unknown Big Brook (Double Mer) 540820 585508 W U Unknown Big Brook (Michaels River) 544109 574730 W N Not Threatened With Loss 427 Big Island Brook 550454 591205 W U Unknown NASCO Rivers Database Report Page 1 of 247 Jurisdiction: Canada Region/Province: Labrador Conservation Requirements (# fish) Catchment Length Flow Latitude Longitude Category Area (km2) (km) (m3/s) Total 1SW MSW Big River 545014 585613 W N Not Threatened With Loss Big River 533127 593958 W U Unknown Bills Brook 533004 561015 W U Unknown Birchy Narrows Brook (St. Michael's Bay) 524317 560325 W U Unknown Black Bay Brook 514644 562054 W U Unknown Black Bear River 531800 555525 W N Not Threatened -

Marginal Seas Around the States Gordon Ireland

Louisiana Law Review Volume 2 | Number 2 January 1940 Marginal Seas Around the States Gordon Ireland Repository Citation Gordon Ireland, Marginal Seas Around the States, 2 La. L. Rev. (1940) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marginal Seas Around the States GORDON IRELAND* THE CONTROVERSY Our Navy, which admits that for a delightful period in the West Indies it "made not one single mistake,"1 is not always equally fortunate in home waters, and on the coast of California seems to be particularly unlucky. There is no question this time of piling up a destroyer squadron on jagged gray rocks; but an attempt to take advantage of a fight among local oil and political interests to gain for itself property and power ran headlong into legislative and legal reefs which are as yet uncleared. The gold striped arms dropped the melon halfway to the fence, and the loud resulting squash aroused not only the owners but some of the neighbors. The Board of Strategy (Domestic) stands at atten- tion beside its blackboard, wondering glumly where the cus- tomary rote formula of first-line-of-defense-brave-and-bold-grab- it went astray, and is still foggily trying to perceive how ques- tions of constitutional and international law could possibly have obtruded themselves into the issue. -

Ph River, Brook and Tributary Sites the Normal Ph Range For

2016 Parameter Data: pH River, Brook and Tributary Sites The standard measurement of acidity is pH. A pH of less than 7 is acidic; above pH 7 is alkaline, also known by the term “basic.” The pH measurement is a logarithmic measurement, which means that each unit decrease in pH equals a ten-fold increase in acidity. In other words, pH 5 water is ten times more acidic than pH 6 water. Aquatic organisms need the pH of their water body to be within a certain range for optimal growth and survival. Although each organism has an ideal pH, most aquatic organisms prefer pH of 6.5 – 8.0. Watershed LOCATION MAY JUNE JULY AUG. SEPT. OCT. Miniumum Code RIVERS - - - - - - Standard pH units - - - - - - A Annaquatucket River - 7.2 6.9 6.6 6.8 6.9 6.7 6.6 Belleville @ Railroad Crossing WD Ashaway River @ Rte 216 6.8 6.6 6.5 6.8 7.1 6.8 6.5 WD Beaver River @ Rte 138 6.3 6.5 6.6 6.8 6.3 6.1 6.1 NA Buckeye Brook #1 @ Novelty Rd 7.0 7.2 6.5 7.2 6.9 7.0 6.5 NA Buckeye Brk #2 @ Lockwood Brk - 6.7 6.9 6.8 - - 6.7 NA Buckeye Brk #3 @ Warner Brook 6.7 6.5 6.4 6.5 6.5 - 6.4 NA Buckeye Brook #4 @ Mill Cove 6.9 7.0 6.4 7.0 7.0 - 6.4 WD Falls River D - Step Stone Falls 6.4 6.4 6.6 6.5 6.6 6.3 6.3 WD Falls River C - Austin Farm Rd. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

Paddleri 2008 North Kingstown, RI 02852

Rhode Island Blueways Alliance PO Box 1565 PaddleRI 2008 North Kingstown, RI 02852 Celebrating Paddling Chair: Keith Gonsalves On RI’s Rivers and Bay Vice Chair: Bruce Hooke Secretary: Terry Meyer Treasurer: Meg Kerr The PaddleRI 2008 celebration was a huge success with over 200 paddlers participating. PaddleRI was sponsored by the RI Blueways Alliance but the individual trips were organized and hosted by local organizations – watershed councils, Save the Bay and local conservation commissions. The celebration would not have been possible without their enthusiastic participation. The RI Blueways Alliance mission is to develop a water trail network linking Rhode Island’s rivers, lakes and ponds to Narragansett Bay and to use the trail to promote safety, conservation, recreation and economic development. PaddleRI 2008 celebrated the network of paddling opportunities that make up our water trail network. We would like to thank our sponsors -- the New England Grassroots Environmental Fund, the RI Resource Conservation & Development Area Council and the Rhode Island Foundation. Salt Ponds Spring Paddle - Ninigret Pond Saturday, May 31: The Salt Ponds Coalition’s trip was planned for May 31, but the paddle was postponed due to weather. On June 1, about 30 paddlers arrived at the US Fish & Wildlife kayak launch accessed through Ninigret Park at 8:30am with plans to get underway by 9:00am. But Mother Nature had other plans…. The fog was so thick that you couldn’t see where to paddle. Paddlers waited, listening to presentations by the US Fish & Wildlife Service and the Salt Pond’s Coalition’s Art Ganz, hoping for better conditions. -

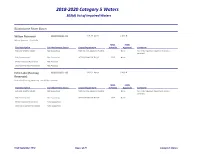

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED