Published in Current Biography Magazine New York Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17-PR-Taylor

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 6, 2017 Media Contact: NextMove Dance Anne-Marie Mulgrew, Director of EducaAon & Special Projects 215-636-9000 ext. 110, [email protected] Editors: Images are available upon request. Paul Taylor Dance Company performs three of Mr. Taylor’s Master Works November 2-5 (Philadelphia, PA) The legendary Paul Taylor Dance Company brings a rare program featuring three of Taylor’s classic works for NextMove Dance’s 2017-2018 Season with five performances November 2-5, at the Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA. The program includes Arden Court (1981), Company B (1991) and Esplanade (1975) Performances take place Thursday, November 2 at 7:30pm; Friday, November 3 at 8:00pm; Saturday, November 4 at 2:00pm and 8:00 pm; and Sunday November 5 at 3pm. Tickets are $20-$62 and can be purchased in person at the Prince Theater Box Office, by phone 215-422-4580 or online h`p://princetheater.org/next-move. Opening the program is the romanAc and uplibing Arden Court for nine dancers set to music by 18th century Baroque English composer William Boyce. This 23-minute work showcases the virtuosity of the six male dancers in effortless yet weighted jumps and changes in speed and dynamic level. Interspersing the ensemble secAons are tender yet whimsical duets. Bare- torso male dancers are in Aghts with colored spots and women are in matching chiffon dresses designed by Gene Moore. Clive Barnes of the New York Post noted “One of the few great art works created in [the 20th] century… exploring a new movement field of love and relaAonship. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Informance 2008

INFORMANCE - MARCH 26, 2008 How can we know the dancer from the dance?” – Martha Graham, Murray Louis, and Bill T. Jones I begin this Informance talk by thanking Linda Roberts and Lori Katterhenry. In early November (the 9th, to be exact), Lori asked me if -- in view of my “obvious enthusiasm and expertise” -- I would be interested in writing study guides for the three guest artist works of the 2007-08 MSU Dance Program: Steps in the Street, by Martha Graham; Four Brubeck Pieces, by Murray Louis; and D-Man in the Waters by Bill T. Jones. “We have never done this before,” Lori said, “and I know it is quite common in theater.” …“Great idea,” Linda Roberts declared the next day, “This information would be very useful for the Informance. I know the students are interested in discussing the movement philosophies and stylistic differences of the three choreographers, and the challenges these elements present in performing and bringing to life the reconstructed dances we are rehearsing.” A few days thereafter, Lori , Linda and I were brainstorming in Lori’s spacious executive office suite and I cautioned them that I was not a dance critic by training; I am an historian and biographer. They were well aware, and that was precisely the reason they asked me to become involved. They were looking for insights about the “historical” side to each work, the social and cultural circumstances that engendered them, the aesthetic contexts against which they were created. I then said that I was not sure I would end up doing actual “study guides,” per se. -

In This Issue

FALL 2019 IN THIS ISSUE JONATHAN BISS CELEBRATING BEETHOVEN: PART I November 5 DANISH STRING QUARTET November 7 PILOBOLUS COME TO YOUR SENSES November 14–16 GABRIEL KAHANE November 23 MFA IN Fall 2019 | Volume 16, No. 2 ARTS LEADERSHIP FEATURE In This Issue Feature 3 ‘Indecent,’ or What it Means to Create Queer Jewish Theatre in Seattle Dialogue 9 Meet the Host of Tiny Tots Concert Series 13 We’re Celebrating 50 Years Empowering a new wave of Arts, Culture and Community of socially responsible Intermission Brain arts professionals Transmission 12 Test yourself with our Online and in-person trivia quiz! information sessions Upcoming Events seattleu.edu/artsleaderhip/graduate 15 Fall 2019 PAUL HEPPNER President Encore Stages is an Encore arts MIKE HATHAWAY Senior Vice President program that features stories Encore Ad 8-27-19.indd 1 8/27/19 1:42 PM KAJSA PUCKETT Vice President, about our local arts community Sales & Marketing alongside information about GENAY GENEREUX Accounting & performances. Encore Stages is Office Manager a publication of Encore Media Production Group. We also publish specialty SUSAN PETERSON Vice President, Production publications, including the SIFF JENNIFER SUGDEN Assistant Production Guide and Catalog, Official Seattle Manager ANA ALVIRA, STEVIE VANBRONKHORST Pride Guide, and the Seafair Production Artists and Graphic Designers Commemorative Magazine. Learn more at encorespotlight.com. Sales MARILYN KALLINS, TERRI REED Encore Stages features the San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives BRIEANNA HANSEN, AMELIA HEPPNER, following organizations: ANN MANNING Seattle Area Account Executives CAROL YIP Sales Coordinator Marketing SHAUN SWICK Senior Designer & Digital Lead CIARA CAYA Marketing Coordinator Encore Media Group 425 North 85th Street • Seattle, WA 98103 800.308.2898 • 206.443.0445 [email protected] encoremediagroup.com Encore Arts Programs and Encore Stages are published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

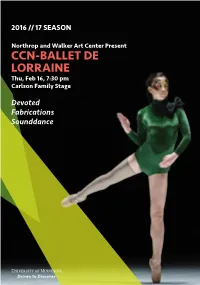

CCN-BALLET DE LORRAINE Thu, Feb 16, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2016 // 17 SEASON Northrop and Walker Art Center Present CCN-BALLET DE LORRAINE Thu, Feb 16, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage Devoted Fabrications Sounddance Dear Friends of Northrop, Northrop at the University of Minnesota and Walker Art Center Present Tonight, we collaborate with Walker Art Center as part of their major survey: Merce Cunningham: Common Time, offering two of Cunningham’s groundbreaking choreographic works. The program begins with Devoted, a commissioned work by the trend setting choreographic duo Cecilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud. Infused with current dance hall and pop culture, CCN-BALLET DE these French choreographers are clearly influenced by modern and even post-modern American dance history—history that was forever changed by Cunningham's impact. LORRAINE Fabrications, the second work on our program, actually had its world premiere right here at Northrop in 1987, with Cunningham dancing, as he did in every performance by his company until he was 70. When he died a few months after his 90th birthday, he Choreographer and General Director had won every choreographic award and accolade imaginable, PETTER JACOBSSON Christine Tschida. Photo by Tim Rummelhoff. and left a legacy of nearly 200 works. It’s interesting to think about the audience who sat here at Northrop 30 years ago, and their world. Choreographer and Coordinator of Research Ronald Reagan was in his second term in the White House and had just struggled through a government THOMAS CALEY shutdown. News of the Iran-Contra Scandal had recently broken. Mad Cow Disease was discovered in the U.K., and the Minnesota Twins would go on to win their first World Series later that year. -

For Immediate Release Contact: Elizabeth Cooke Communications Manager [email protected] (212) 691-6500 X210

For Immediate Release Contact: Elizabeth Cooke Communications Manager [email protected] (212) 691-6500 x210 NEW YORK LIVE ARTS presents Fresh Tracks Dec 13 – 15 at 7:30pm New York, NY, November 15, 2012 – New York Live Arts will present Fresh Tracks, the latest installment of the Fresh Tracks Performance & Residency Program, Dec 13 – 15 at 7:30pm. The 2012-13 Fresh Tracks Artists include Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie, Franklin Diaz, Megan Kendizor, Molly Poerstel-Taylor, Michal Samama and Parul Shah. Created in 1965 by Dance Theater Workshop and now continued as a signature program of New York Live Arts, the Fresh Tracks Performance and Residency Program selects six early career artists annually to receive comprehensive performance and residency support. The program begins with a showcase performance in New York Live Arts’ Bessie Schönberg Theater. Following the performance, each artist receives a 50-hour creative residency in the New York Live Arts studios for research and development of new work. Additionally, artists receive introductory level professional development workshops in marketing, fundraising and career development. Under the guidance of Artistic Advisor Levi Gonzalez, Fresh Tracks artists participate in dialogue sessions facilitating open discussion about their creative process, as well as one-on-one consultations. Performances will take place at New York Live Arts’ Bessie Schönberg Theater. Come Early Conversations and Stay Late Discussions will also be featured with two shows (see complete schedule below). Tickets are $20 and $15. Tickets may be purchased online at tickets.newyorklivearts.org, by phone at 212-924-0077 and in person at the box office. Box office hours are Monday to Friday from 1 to 9pm, and Saturday and Sunday from 12 to 8pm. -

Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON

THEATER EMORY A Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON Three Productions in Rotating Repertory The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity October 23-24, November 3-4, 8-9 • Written by Kristoffer Diaz • Directed by Lydia Fort A satirical smack-down of culture, stereotypes, and geopolitics set in the world of wrestling entertainment. Mary Gray Munroe Theater We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Südwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 October 25-26, 30-31, November 10-11 • Written by Jackie Sibblies Drury • Directed by Eric J. Little The story of the first genocide of the twentieth century—but whose story is actually being told? Mary Gray Munroe Theater The Moors October 27-28, November 1-2, 6-7 • Written by Jen Silverman • Directed by Matt Huff In this dark comedy, two sisters and a dog dream of love and power on the bleak English moors. Mary Gray Munroe Theater Sara Juli’s Tense Vagina: an actual diagnosis November 29-30 • Written, directed, and performed by Sara Juli Visiting artist Sara Juli presents her solo performance about motherhood. Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Tatischeff Café April 4-14 • Written by John Ammerman • Directed by John Ammerman and Clinton Wade Thorton A comic pantomime tribute to great filmmaker and mime Jacques Tati Mary Gray Munroe Theater 2 2017-2018 SEASON Midnight Pillow September 21 - October 1, 2017 • Inspired by Mary Shelley • Directed by Park Krausen 13 Playwrights, 6 Actors, and a bedroom. What dreams haunt your midnight pillow? Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Anointing of Dracula: A Grand Guignol October 26 - November 5, 2017 • Written and directed by Brent Glenn • Inspired by the works of Bram Stoker and others. -

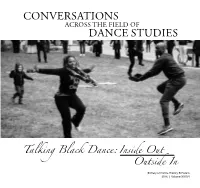

Talking Black Dance: Inside Out

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Talking Black Dance: Inside Out OutsideSociety of Dance InHistory Scholars 2016 | Volume XXXVI Table of Contents A Word from the Guest Editors ................................................4 The Mis-Education of the Global Hip-Hop Community: Reflections of Two Dance Teachers: Teaching and In Conversation with Duane Lee Holland | Learning Baakasimba Dance- In and Out of Africa | Tanya Calamoneri.............................................................................42 Jill Pribyl & Ibanda Grace Flavia.......................................................86 TALKING BLACK DANCE: INSIDE OUT .................6 Mackenson Israel Blanchard on Hip-Hop Dance Choreographing the Individual: Andréya Ouamba’s Talking Black Dance | in Haiti | Mario LaMothe ...............................................................46 Contemporary (African) Dance Approach | Thomas F. DeFrantz & Takiyah Nur Amin ...........................................8 “Recipe for Elevation” | Dionne C. Griffiths ..............................52 Amy Swanson...................................................................................93 Legacy, Evolution and Transcendence When Dance Voices Protest | Dancing Dakar, 2011-2013 | Keith Hennessy ..........................98 In “The Magic of Katherine Dunham” | Gregory King and Ellen Chenoweth .................................................53 Whiteness Revisited: Reflections of a White Mother | Joshua Legg & April Berry ................................................................12 -

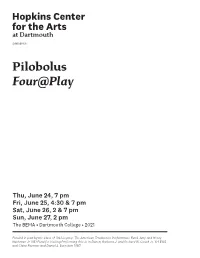

Pilobolus Four@Play

presents Pilobolus Four@Play Thu, June 24, 7 pm Fri, June 25, 4:30 & 7 pm Sat, June 26, 2 & 7 pm Sun, June 27, 2 pm The BEMA • Dartmouth College • 2021 Funded in part by the Class of 1961 Legacy: The American Tradition in Performance Fund, Amy and Henry Nachman Jr 1951 Fund for Visiting Performing Artists in Dance, Barbara J. and Richard W. Couch Jr. ’64 E’65 and Claire Foerster and Daniel S. Bernstein 1987. Program WALKLYNDON (1971) Choreographed by Robby Barnett, Lee Harris, Moses Pendleton and Jonathan Wolken Performed by Quincy Ellis, Marlon Feliz, Casey Howes and Paul Liu Costumes: Kitty Daly Lighting: Neil Peter Jampolis FEMME NOIRE (1999) Choreographed by Alison Chase in collaboration with Rebecca Anderson and Rebecca Stenn Performed by Casey Howes Music: Paul Sullivan Costumes: Angelina Avallone Costume Construction: Parsons-Meares Lighting: Stephen Strawbridge This piece was made possible in part by support from the Connecticut Commission on the Arts. Solo from the EMPTY SUITOR (1980) Choreographed by Michael Tracy Performed by Paul Liu Music: Ben Webster, “Sweet Georgia Brown” used by permission Warner Bros. Costumes: Kitty Daly Lighting: Neil Peter Jampolis ALRAUNE (1975) Choreographed by Alison Chase and Moses Pendleton Performed by Quincy Ellis and Marlon Feliz Music: Robert Dennis Costumes: Malcolm McCormick Lighting: Neil Peter Jampolis About Pilobolus Since 1971, Pilobolus has tested the limits of human Pilobolus Education has been at the forefront of the physicality to explore the beauty and power of company’s activities offering unique programming connected bodies. We continue to bring this tradition for schools, colleges and public arts organizations through our post-disciplinary collaborations with as well as classes and leadership workshops for some of the greatest influencers, thinkers and corporate executives, employees and business creators in the world. -

Deelnameniveaus Bewegingsonderwijs in De

Formatief evalueren en de DTT Engels: aan de slag Dansapedia Dansbegrippen - Danssoorten - Personen en gezelschappen SLO • nationaal expertisecentrum leerplanontwikkeling Auteur[s] slo Dansapedia Dansbegrippen - Danssoorten - Personen en gezelschappen Disclaimer De Dansapedia was tot voor kort onderdeel van de inmiddels opgeheven website Danstijd.slo.nl. Om de inhoud van de Dansapedia toch beschikbaar te houden voor docenten (en hun leerlingen), is er voor gekozen om hiervan een document (pdf) te maken. De Dansapedia is op deze manier nog te gebruiken om informatie op te zoeken over ruim 600 items met betrekking tot dansbegrippen, danssoorten en personen (choreografen, dansers, danseressen, gezelschappen). NB. De teksten zijn integraal van de website uit 2008 overgenomen. Daarbij zijn alle verwijzingen en hyperlinks noodzakelijkerwijs verwijderd. Verantwoording SLO (nationaal expertisecentrum leerplanontwikkeling), Enschede Alle rechten voorbehouden. Mits de bron wordt vermeld is het toegestaan om zonder voorafgaande toestemming van de uitgever informatie uit de Dansapedia geheel of gedeeltelijk te kopiëren dan wel op andere wijze te vermenigvuldigen, tenzij expliciet anders is aangegeven. Hoewel bij het samenstellen van de inhoud van de Dansapedia de grootst mogelijke zorgvuldigheid is betracht, sluit SLO iedere aansprakelijkheid uit voor onjuistheden, onvolledigheden, prijs- en typefouten en eventuele gevolgen van het handelen op grond van informatie in dit document. Auteurs (2008): Wieneke van Breukelen, Martin Bijkerk, Jolanda Keurentjes, Isabella Lanz, Pascal Marsman, Ruth Naber en Sofie van Sommen. Redactie (2008) Wieneke van Breukelen (NBDK), Pascal Marsman (SLO). Verdere informatie E-mail: [email protected] Inhoud 1. Overzicht dansbegrippen (alfabetische volgorde) 5 2. Danssoorten 50 3. Overzicht personen en gezelschappen 67 Referenties 90 1. Overzicht dansbegrippen (alfabetische volgorde) Abstracte dans, Abstract ballet Dans/ballet zonder verhaal of boodschap. -

Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 X132 [email protected]

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] PILOBOLUS PRESENTS COME TO YOUR SENSES IN THE TED SHAWN THEATRE, JUNE 27-JULY 1 June 26, 2018 (Becket, MA) Award-winning Pilobolus returns to the Ted Shawn Theatre with Come To Your Senses, a program about accessing all five senses, June 27-July 1. The “mind-blowing troupe of wildly creative and physically daring dancers” (NY Newsday) guides audiences through a multi-sensory experience alongside repertory classics and new work, including the first all-women trio in the company’s history. The Washington Post praises, “Pilobolus embodies a large part of what the best in contemporary dance is all about: discovery.” “We are thrilled to have Pilobolus return to Jacob’s Pillow and to see the work they created for the Inside/Out stage last year reimagined in the historic Ted Shawn Theatre. Their program will also include repertoire that activates all of our senses while celebrating the beauty and power of the human body.” say Jacob’s Pillow Director, Pamela Tatge. Founded in 1971 with their Pillow debut just three years later, Pilobolus is known for its unique, collaborative dance creations which break movement and visual boundaries to reveal the graphic capabilities of the human body in surprising ways. Named after the light-loving fungus Pilobolus crystallinus, the company performs for over 300,000 people each year and has created over 120 works with with their rare vocabulary of humor, invention, and drama.