Erick Hawkins' Collaborations in the Choreographing of Plains Daybreak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

Press Release Contact: Whitney Museum of American Art Whitney Museum of American Art 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Stephen Soba, Kira Garcia New York, NY 10021 (212) 570-3633 www.whitney.org/press www.whitney.org/press March 2007 Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] WHITNEY MUSEUM TO PRESENT A TRIBUTE TO LINCOLN KIRSTEIN BEGINNING APRIL 25, 2007 Pavel Tchelitchew, Portrait of Lincoln Kirstein, 1937 Courtesy of The School of American Ballet, Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson The Whitney Museum of American Art is observing the 100th anniversary of Lincoln Kirstein’s birth with an exhibition focusing on a diverse trio of artists from Kirstein’s circle: Walker Evans, Elie Nadelman, and Pavel Tchelitchew. Lincoln Kirstein: An Anniversary Celebration, conceived by guest curator Jerry L. Thompson, working with Elisabeth Sussman and Carter Foster, opens in the Museum’s 5th-floor Ames Gallery on April 25, 2007. Selections from Kirstein’s writings form the basis of the labels and wall texts. Lincoln Kirstein (1906-96), a noted writer, scholar, collector, impresario, champion of artists, and a hugely influential force in American culture, engaged with many notable artistic and literary figures, and helped shape the way the arts developed in America from the late 1920s onward. His involvement with choreographer George Balanchine, with whom he founded the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet, is perhaps his best known accomplishment. This exhibition focuses on the photographer Walker Evans, the sculptor Elie Nadelman, and the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, each of whom was important to Kirstein. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's Theses UARC.0666

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833tht No online items Finding Aid for the University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses UARC.0666 Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 1998 June; revised by Katharine A. Lawrie; 2013 October. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 August 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections UARC.0666 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses Creator: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Identifier/Call Number: UARC.0666 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet(30 cartons) Date (inclusive): 1958-1994 Abstract: Record Series 666 contains Master's theses generated within the UCLA Dance Department between 1958 and 1988. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. All requests for permission to publish or quote must be submitted in writing to the UCLA University Archivist. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses (University Archives Record Series 666). UCLA Library Special Collections, University Archives, University of California, Los Angeles. -

17-PR-Taylor

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 6, 2017 Media Contact: NextMove Dance Anne-Marie Mulgrew, Director of EducaAon & Special Projects 215-636-9000 ext. 110, [email protected] Editors: Images are available upon request. Paul Taylor Dance Company performs three of Mr. Taylor’s Master Works November 2-5 (Philadelphia, PA) The legendary Paul Taylor Dance Company brings a rare program featuring three of Taylor’s classic works for NextMove Dance’s 2017-2018 Season with five performances November 2-5, at the Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA. The program includes Arden Court (1981), Company B (1991) and Esplanade (1975) Performances take place Thursday, November 2 at 7:30pm; Friday, November 3 at 8:00pm; Saturday, November 4 at 2:00pm and 8:00 pm; and Sunday November 5 at 3pm. Tickets are $20-$62 and can be purchased in person at the Prince Theater Box Office, by phone 215-422-4580 or online h`p://princetheater.org/next-move. Opening the program is the romanAc and uplibing Arden Court for nine dancers set to music by 18th century Baroque English composer William Boyce. This 23-minute work showcases the virtuosity of the six male dancers in effortless yet weighted jumps and changes in speed and dynamic level. Interspersing the ensemble secAons are tender yet whimsical duets. Bare- torso male dancers are in Aghts with colored spots and women are in matching chiffon dresses designed by Gene Moore. Clive Barnes of the New York Post noted “One of the few great art works created in [the 20th] century… exploring a new movement field of love and relaAonship. -

An Open Door: the Cathedral's Web Portal

Fall 2013 1047 Amsterdam Avenue Volume 13 Number 62 at 112th Street New York, NY 10025 (212) 316-7540 stjohndivine.org Fall 2013 at the Cathedral An Open Door: The Cathedral’s Web Portal cross the city, the great hubs of communication a plethora of new opportunities, many of which society is WHAT’s InsIDE pulse: churches, museums, universities, only beginning to understand. As accustomed as we have government offices, the Stock Exchange. Each become in recent years to having the world at our fingertips, The Cathedral's Web Portal Things That Go Bump can be seen as a microcosm of the city or there is little doubt that in 10, 20, 50 years that connection In the Night Great Music in a Great Space the world. Many, including the Cathedral, were will be more profoundly woven into our culture. The human The New Season founded with this in mind. But in 2013, no heart in prayer, the human voice in song, the human spirit in Blessing of the Animals discussion about connections or centers of communication can poetry: all of these resonate within Cathedral walls, but need Long Summer Days A The Viewer's Salon help but reference the World Wide Web. The Web has only been not be limited by geography. Whether the Internet as a whole Nightwatch's ’13–’14 Season around for a blink of an eye of human history, and only for a works to bring people together and foster understanding is Dean's Meditation: small part of the Cathedral’s existence, but its promise reflects up to each of us as users. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

NETC News, Vol. 15, No. 3, Summer 2006

A Quarterly Publication of the New England Theater NETCNews Conference, Inc. volume 15 number 3 summer 2006 The Future is Now! NETC Gassner Competition inside Schwartz and Gleason Among 2006 a Global Event this issue New Haven Convention Highlights April 15th wasn’t just income tax day—it was also the by Tim Fitzgerald, deadline for mailing submissions for NETC’s John 2006 Convention Advisor/ Awards Chairperson Gassner Memorial Playwrighting Award. The award Area News was established in 1967 in memory of John Gassner, page 2 Mark your calendars now for the 2006 New England critic, editor and teacher. More than 300 scripts were Theatre Conference annual convention. The dates are submitted—about a five-fold increase from previous November 16–19, and the place is Omni New Haven years—following an extensive promotional campaign. Opportunities Hotel in the heart of one of the nation’s most exciting page 5 theatre cities—and just an hour from the Big Apple itself! This promises to be a true extravanganza, with We read tragedies, melodramas, verse Ovations workshops and inteviews by some of the leading per- dramas, biographies, farces—everything. sonalities of current American theatre, working today Some have that particular sort of detail that page 6 to create the theatre of tomorrow. The Future is Now! shows that they’re autobiographical, and Upcoming Events Our Major Award recipient this others are utterly fantastic. year will be none other than page 8 the Wicked man himself, Stephen Schwartz. Schwartz is “This year’s submissions really show that the Gassner an award winning composer Award has become one of the major playwrighting and lyricist, known for his work awards,” said the Gassner Committee Chairman, on Broadway in Wicked, Pippin, Steve Capra. -

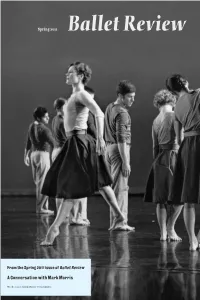

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

Oral History Interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23

Oral history interview with Walker Evans, 1971 Oct. 13-Dec. 23 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Walker Evans conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interview took place at the home of Walker Evans in Connecticut on October 13, 1971 and in his apartment in New York City on December 23, 1971. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: It’s October 13, 1971 – Paul Cummings talking to Walker Evans at his home in Connecticut with all the beautiful trees and leaves around today. It’s gorgeous here. You were born in Kenilworth, Illinois – right? WALKER EVANS: Not at all. St. Louis. There’s a big difference. Though in St. Louis it was just babyhood, so really it amounts to the same thing. PAUL CUMMINGS: St. Louis, Missouri. WALKER EVANS: I think I must have been two years old when we left St. Louis; I was a baby and therefore knew nothing. PAUL CUMMINGS: You moved to Illinois. Do you know why your family moved at that point? WALKER EVANS: Sure. Business. There was an opening in an advertising agency called Lord & Thomas, a very famous one. I think Lasker was head of it. Business was just starting then, that is, advertising was just becoming an American profession I suppose you would call it. Anyway, it was very naïve and not at all corrupt the way it became later. -

An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015

Summer 2015 Ball et Review An Early American Sleeping Beauty from Ballet Review Summer 2015 CoverphotographbyCostas:WendyWhelanandNikolajHübbe inBalanchine’sLaSonnambula . © 2015 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Brooklyn – Susanna Sloat 5 Berlin – Darrell Wilkins 7 London – Leigh Witchel 9 New York – Susanna Sloat 10 Toronto – Gary Smith 12 New York – Karen Greenspan 14 London – David Mead 15 New York – Susanna Sloat 16 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 19 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 21 New York – Harris Green 39 22 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 23 London – Leigh Witchel Ballet Review 43.2 24 Brooklyn – Darrell Wilkins Summer 2015 26 El Paso – Karen Greenspan Editor and Designer: 31 San Francisco – Rachel Howard Marvin Hoshino 32 Chicago – Joseph Houseal Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Sharon Skeel 34 Early American Annals of Senior Editor: Don Daniels The Sleeping Beauty Associate Editor: 54 Christopher Caines Joel Lobenthal 39 Tharp and Tudor for a Associate Editor: New Generation Larry Kaplan Michael Langlois Webmaster: 46 A Conversation with Ohad Naharin David S. Weiss Copy Editors: Leigh Witchel Barbara Palf y* 54 Ashton Celebrated Naomi Mindlin Joel Lobenthal Photographers: Tom Brazil 62 62 A Conversation with Nora White Costas Nina Alovert Associates: 70 The Mikhailovsky Ballet Peter Anastos Robert Greskovic David Mead George Jackson 76 A Conversation with Peter Wright Elizabeth Kendall Paul Parish James Sutton Nancy Reynolds 89 Indianapolis Evening of Stars James SuZon David Vaughan Leigh Witchel Edward Willinger 70 94 La Sylphide Sarah C. Woodcock Jay Rogoff 98 A Conversation with Wendy Whelan 106 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 110 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Costas: Wendy Whelan 116 Check It Out and Nikolaj Hübbe in La Sonnambula . -

Informance 2008

INFORMANCE - MARCH 26, 2008 How can we know the dancer from the dance?” – Martha Graham, Murray Louis, and Bill T. Jones I begin this Informance talk by thanking Linda Roberts and Lori Katterhenry. In early November (the 9th, to be exact), Lori asked me if -- in view of my “obvious enthusiasm and expertise” -- I would be interested in writing study guides for the three guest artist works of the 2007-08 MSU Dance Program: Steps in the Street, by Martha Graham; Four Brubeck Pieces, by Murray Louis; and D-Man in the Waters by Bill T. Jones. “We have never done this before,” Lori said, “and I know it is quite common in theater.” …“Great idea,” Linda Roberts declared the next day, “This information would be very useful for the Informance. I know the students are interested in discussing the movement philosophies and stylistic differences of the three choreographers, and the challenges these elements present in performing and bringing to life the reconstructed dances we are rehearsing.” A few days thereafter, Lori , Linda and I were brainstorming in Lori’s spacious executive office suite and I cautioned them that I was not a dance critic by training; I am an historian and biographer. They were well aware, and that was precisely the reason they asked me to become involved. They were looking for insights about the “historical” side to each work, the social and cultural circumstances that engendered them, the aesthetic contexts against which they were created. I then said that I was not sure I would end up doing actual “study guides,” per se. -

Dance Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb58d No online items Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Processed by Emma Kheradyar. Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Dance Photograph MS-P021 1 Collection Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Collection number: MS-P021 Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries University of California Irvine, California Contact Information Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html Processed by: Emma Kheradyar Date Completed: July 1997 Encoded by: James Ryan © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Dance Photograph Collection, Date (inclusive): 1906-1970 Collection number: MS-P021 Extent: Number of containers: 5 document boxes Linear feet: 2 Repository: University of California, Irvine. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Irvine, California 92623-9557 Abstract: The Dance Photograph Collection is comprised of publicity images, taken by commercial photographers and stamped with credit lines. Items date from 1906 to 1970. The images, all silver gelatin, document the repertoires of six major companies; choreographers' original works, primarily in modern and post-modern dance; and individual, internationally known dancers in some of their significant roles.