The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

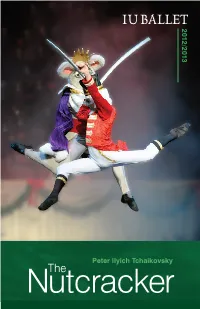

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

Danc Scapes Choreographers 2015

dancE scapes Choreographers 2015 Amy Cain was born in Jacksonville, Florida and grew up in The Woodlands/Spring area of Texas. Her 30+ years of dance training include working with various instructors and choreographers nationwide and abroad. She has also been coached privately and been inspired for most of her dance career by Ken McCulloch, co-owner of NHPA™. Amy is in her 22nd year of partnership in directing NHPA™, named one of the “Top 50 Studios On the Move” by Dance Teacher Magazine in 2006, and has also been co-director of Revolve Dance Company for 10 years. She also shares her teaching experience as a jazz instructor for the upper level students at Houston Ballet Academy. Amy has danced professionally with Ad Deum, DWDT, and Amy Ell’s Vault, and her choreographic works have been presented in Italy, Mexico, and at many Houston area events. In June 2014 Amy’s piece “Angsters”, performed by Revolve Dance Company, was presented as a short film produced by Gothic South Productions at the Dance Camera estW Festival in L.A. where it received the “Audience Favorite” award. This fall “Angsters” will be screened on Opening Night at the San Francisco Dance Film Festival in California, and on the first screening weekend at the Sans Souci Festival of Dance Cinema in Boulder, Colorado. Dawn Dippel (co-owner) has been dancing most of her life and is now co-owner of NHPA™, co-Director and founding member of Revolve Dance Company, and a former member of the Dominic Walsh Dance Theatre. She grew up in the Houston area, graduated from Houston’s High School for the Performing & Visual Arts Dance Department, and since then has been training in and outside of Houston. -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Mitchell, Arthur, 1934-2018 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Arthur Mitchell, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:21:20). Description: Abstract: Dancer, choreographer, and artistic director Arthur Mitchell (1934 - 2018 ) was a principal dancer for the New York City Ballet for fifteen years. In 1969, he co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first African American classical ballet company and school. Mitchell was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_034 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Dancer, choreographer and artistic director Arthur Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934 in Harlem, New York to Arthur Mitchell, Sr. and Willie Hearns Mitchell. He attended the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. In addition to academics, Mitchell was a member of the New Dance Group, the Choreographers Workshop, Donald McKayle and Company, and High School of Performing Arts’ Repertory Dance Company. After graduating from high school in 1952, Mitchell received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American Ballet. In 1954, Mitchell danced on Broadway in House of Flowers with Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Donald McKayle, Alvin Ailey and Pearl Bailey. -

17-PR-Taylor

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 6, 2017 Media Contact: NextMove Dance Anne-Marie Mulgrew, Director of EducaAon & Special Projects 215-636-9000 ext. 110, [email protected] Editors: Images are available upon request. Paul Taylor Dance Company performs three of Mr. Taylor’s Master Works November 2-5 (Philadelphia, PA) The legendary Paul Taylor Dance Company brings a rare program featuring three of Taylor’s classic works for NextMove Dance’s 2017-2018 Season with five performances November 2-5, at the Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA. The program includes Arden Court (1981), Company B (1991) and Esplanade (1975) Performances take place Thursday, November 2 at 7:30pm; Friday, November 3 at 8:00pm; Saturday, November 4 at 2:00pm and 8:00 pm; and Sunday November 5 at 3pm. Tickets are $20-$62 and can be purchased in person at the Prince Theater Box Office, by phone 215-422-4580 or online h`p://princetheater.org/next-move. Opening the program is the romanAc and uplibing Arden Court for nine dancers set to music by 18th century Baroque English composer William Boyce. This 23-minute work showcases the virtuosity of the six male dancers in effortless yet weighted jumps and changes in speed and dynamic level. Interspersing the ensemble secAons are tender yet whimsical duets. Bare- torso male dancers are in Aghts with colored spots and women are in matching chiffon dresses designed by Gene Moore. Clive Barnes of the New York Post noted “One of the few great art works created in [the 20th] century… exploring a new movement field of love and relaAonship. -

The BALLET RUSSE De Monte Carlo

The RECORD SHOP Phil Hart, Mgr. presents The BALLET RUSSE de Monte Carlo IN THE PORTLAND AUDITORIUM Thursday, November 16,1944 AT 8:30 P. M. * PLEASE NOTE the following cast changes, due to a leg injury sustained by MR. FRANKLIN. In Le Bourgeois Gentilhornrne Cleonte M. Nicholas MAGALLANES In Gaite Parisienne Tbe Baron M. Nihita TALIN In Danses Concertantes Leon DANIELIAN in place of Frederic FRANKLIN In Rodeo Tbe Champion Roper Mr. Herbert BLISS PROGRAM II. A • "*j 3 • ,. y LE BOURGEOIS GENTILHOMME Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Richard Strauss Scenery and costumes by Eugene Berman Scenery executed by E. B. Dunkel Studios Costumes executed by Karinska, Inc. SERENADE This ballet depicts one episode from Moliere's immortal farce, "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme." A young man, Cleonte, is in love with M. Jourdain's daughter, Luetic M. Jourdain disapproves of the match, as Cleonte is not of noble birth and it is M. Choreography by George BALANCHINE Music by P. I. Tschaikowsky Jourdain's lifetime ambition to shed his middle-class status and rise to aristocracy. Cleonte and his valet, Coviel, impersonate respectively the son of the Great Turk and his ambassador, and under this disguise Cleonte asks for the hand of Lucile. Lucile, at first, unaware of Cleonte's disguise, bitterly resents the wedlock and not Costumes by Jean LURCAT Costumes executed by H. MAHIEU, Inc. until Cleonte raises his mask does she willingly consent. In exchange for the hand of his bride, Cleonte makes M. Jourdain a Mamamouchi—a great dignitary of Turkey—"than which there is nothing more noble in the world," by means of an imposing ceremony. -

Miami City Ballet Announces 2016-2017 Season

Media Contact: Samantha Franco Zakarin Martinez Public Relations [email protected] 305.372.2502 MIAMI CITY BALLET ANNOUNCES 2016-2017 SEASON Highlights Include the Classic Full-Length Ballet GISELLE, a World Premiere by ALEXEI RATMANSKY, and Five ComPany Premieres from George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, Twyla TharP, Peter Martins and Sir Kenneth MacMillan Season OPens October 21 In Miami, November 5 In Fort Lauderdale And November 11 In West Palm Beach MIAMI BEACH, FL – (February 29, 2016) – Miami City Ballet’s 2016-2017 season opens October 21 with the classic full-evening ballet Giselle, and adds six major works to the company’s repertoire, including the highly anticipated world Premiere of The Fairy’s Kiss by Alexei Ratmansky. Says Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez, “Miami City Ballet is committed to bringing our audiences the very best of dance’s past, present and future. From a new narrative ballet by today’s most in-demand classical choreographer, Alexei Ratmansky, to five major company premieres, to several well-loved revivals, our new season offers a wide range of the best that dance has to offer, performed by our brilliant and highly individual MCB dancers.” The 2016-2017 Season begins October 21 with performances at the Adrienne Arsht Center in Miami, before moving on to the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach and the Broward Center in Fort Lauderdale; all repertory programs danced to live music provided by the distinguished OPus One Orchestra. Current Miami City Ballet Subscribers are now renewing their preferred seats for the 2016-17 Season at www.miamicityballet.org/subscribe or 877.929.7010. -

Informance 2008

INFORMANCE - MARCH 26, 2008 How can we know the dancer from the dance?” – Martha Graham, Murray Louis, and Bill T. Jones I begin this Informance talk by thanking Linda Roberts and Lori Katterhenry. In early November (the 9th, to be exact), Lori asked me if -- in view of my “obvious enthusiasm and expertise” -- I would be interested in writing study guides for the three guest artist works of the 2007-08 MSU Dance Program: Steps in the Street, by Martha Graham; Four Brubeck Pieces, by Murray Louis; and D-Man in the Waters by Bill T. Jones. “We have never done this before,” Lori said, “and I know it is quite common in theater.” …“Great idea,” Linda Roberts declared the next day, “This information would be very useful for the Informance. I know the students are interested in discussing the movement philosophies and stylistic differences of the three choreographers, and the challenges these elements present in performing and bringing to life the reconstructed dances we are rehearsing.” A few days thereafter, Lori , Linda and I were brainstorming in Lori’s spacious executive office suite and I cautioned them that I was not a dance critic by training; I am an historian and biographer. They were well aware, and that was precisely the reason they asked me to become involved. They were looking for insights about the “historical” side to each work, the social and cultural circumstances that engendered them, the aesthetic contexts against which they were created. I then said that I was not sure I would end up doing actual “study guides,” per se. -

RUSSIAN NATIONAL BALLET SWAN LAKE: Wednesday, January 22, 2020; 7:30 Pm the SLEEPING BEAUTY: Thursday, January 23, 2020; 2 & 7:30 Pm Media Sponsor

RUSSIAN NATIONAL BALLET SWAN LAKE: Wednesday, January 22, 2020; 7:30 pm Media Sponsor THE SLEEPING BEAUTY: Thursday, January 23, 2020; 2 & 7:30 pm A Columbia Artists Production Direct from Moscow, Russia RUSSIAN NATIONAL BALLET COMPANY OF 50 Artistic Director: Elena Radchenko Company Biography The Russian National Ballet Theatre was founded in Moscow during the transitional period of Perestroika in the late 1980s, when many of the great dancers and choreographers of the Soviet Union’s ballet institutions were exercising their new- found creative freedom by starting new, vibrant companies dedicated not only to the timeless tradition of classical Russian Ballet but to invigorate this tradition as the Russians began to accept new developments in the dance from around the world. The company, then titled the Soviet National Ballet, was founded by and incorporated graduates from the great Russian choreographic schools of Moscow, St. Petersburg and Perm. The principal dancers SWAN LAKE Photo: Alexander Daev of the company came from the upper ranks of the great ballet companies and academies of Russia, and the companies of Riga, Kiev and even Warsaw. Today, the Russian National Ballet Theatre SWAN LAKE is its own institution, with over 50 dancers of singular instruction and vast experience, many of whom have been with the company Full-length Ballet in Four Acts since its inception. Music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Choreography by Marius Petipa, Lev Ivanov and Yuri Grigorovich In 1994, the legendary Bolshoi principal dancer Elena Radchenko Restaging by Elena Radchenko, assistant Alexander Daev was selected by Presidential decree to assume the first permanent Synopsis by Vladimir Begichev and Vasily Geltser artistic directorship of the company. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St.