Master, Jonathan Lair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gh4h08w Author Downs, Jordan Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jordan Swan Downs December 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Jonathan Eacott Dr. Randolph Head Dr. J. Sears McGee Copyright by Jordan Swan Downs 2015 The Dissertation of Jordan Swan Downs is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to all of the people who have helped me to complete this dissertation. This project was made possible due to generous financial support form the History Department at UC Riverside and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Other financial support came from the William Andrew’s Clark Memorial Library, the Huntington Library, the Institute of Historical Research in London, and the Santa Barbara Scholarship Foundation. Original material from this dissertation was published by Cambridge University Press in volume 57 of The Historical Journal as “The Curse of Meroz and the English Civil War” (June, 2014). Many librarians have helped me to navigate archives on both sides of the Atlantic. I am especially grateful to those from London’s livery companies, the London Metropolitan Archives, the Guildhall Library, the National Archives, and the British Library, the Bodleian, the Huntington and the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

EDITORIAL HE 55Th Annual Meeting of the Society Was Held at Westi:Hn?Sji

EDITORIAL HE 55th Annual Meeting of the Society was held at Westi:hn?sJI.. Chapel on 12 May, 1954, at 5.30 p.m. There were present T some 65 members and non-members. The resignation of the General Secretary, the Rev. H. Sellers, on his leaving Ilford for Redditch, was accepted with regret; members were glad to hear that the Rev. E.W. Dawe was willing to serve in this capacity, and elected him to the office. The meeting also accepted with regret the resignation of Dr. R. S. Paul, Associate Editor of these Transactions, and expressed its best wishes for his future work as he goes to represent Congre gationalism in a wider sphere at the Ecumenical Institute at Bossey. The other officers were re-elected, with thanks for their continued services, together with those of Mr. Sellers and Dr. Paul. Congregationalists in this country, and especially those interested in our history, have welcomed the return from Grahamstown to this country of Dr. Horton Davies, now Senior Lecturer in Church History at Mansfield and Regent's Park Colleges, Oxford. Those who know his book, The Worship of the English Puritans, will be interested to learn that Dr. Davies is at work on a continuation of this subject. A foretaste of it was enjoyed by the members of our Society in the paper on" Liturgical Reform in Nineteenth-Century English Congre gationalism", which Dr. Davies read at our Annual Meeting, and which is printed within. It was delivered with much charm, vigour and sly humour. It is a thousand pities that the pressure of other, and supposedly more important, meetings always prevents us from following the lecture with a period of questions and discussion. -

The Documentary History of the Westminster Assembly

THE P KESBYTERIAN REVIEW. MANAGING EDITORS : ARCHIBALD A. HODGE, CHARLES A. BRIGGS. ASSOCIATE EDITORS : SAMUEL J. WILSON, JAMES EELLS, FRANCIS L. PATTON, RANSOM B. WELCH, TALBOT W. CHAMBERS. VOLUME I. 1880. NEW YORK: Published for the Presbyterian Review Association, by ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & COMPANY, 900 BROADWAY, COR. 20th STREET. COPYRIGHT, iSSo, BY A. D. F. RANDOLPH * CO. Edward 0. Jenkins, Printer and Stereotyper, jo North William St., New York. TABLE OF CONTENTS. JANUARY. I.— IDEA AND AIMS OF THE PRESBYTERIAN REVIEW, . 3 The Editors. II.— HUME, HUXLEY, AND MIRACLES 8 Prof. W. G. T. Shedd, D.D., LL.D. III.— JUVENAL'S HISTORICAL JUDGMENTS 34 Prof. W. A. Packard, Ph.D. IV.— THE APOLOGETICAL VALUE OF THE TESTAMENTS OF THE XII PATRIARCHS 57 Prof. B. B. Warfield, D.D. V.— NOTES ON THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION IN THE REFORMED CHURCHES OF FRANCE AND FRENCH SWITZER LAND 85 Prof. H. M. Baird, D.D. VI.— RAVENNA 104 Rev. M. R. Vincent, D.D. VII.— DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE WESTMINSTER ASSEM BLY 127 Prof. C. A. Briggs, D.D. VIII.— NOTES AND NOTICES 164 IX.— REVIEWS OF RECENT THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE, . 172 APRIL. I.— THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE KINGS OF ISRAEL AND JUDAH, 211 Prof. W. J. Beecher, D.D. II.— THE CHINESE IN AMERICA 247 Prof. James Eells, D.D. III.— DEACONESSES 268 Prof. A. T. McGill, D.D., LL.D. IV.— HENRY VAUGHAN, THE POET OF LIGHT 291 Rev. S. W. Duffield. V.— THE THEORY OF PROFESSOR KUENEN 304 Rev. T. W. Chambers, D.D. VI.— A PLEA FOR EVANGELICAL APOLOGETICS, . , . 321 Rev. -

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 a Sermon Preached Before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 A sermon preached before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26. of November, 1645 / by Jer.Burroughus. - London : printed for R.Dawlman, 1646. -[6],48p.; 4to, dedn. - Final leaf lacking. Bound with r the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S. SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 438 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons assembled in Parliament at their publique thanksgiving September 7 1641 for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. - [8],64p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : Gauden, J. The love of truth and peace. London, 1641. 1S.SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons, September 7.1641, for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. - London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. -[8],54p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S.SERMONS BURT, Edward, fl.1755 D 695-6 Letters from a gentleman in the north of Scotland to his friend in London : containing the description of a capital town in that northern country, likewise an account of the Highlands. - A new edition, with notes. - London : Gale, Curtis & Fenner, 1815. - 2v. (xxviii, 273p. : xii,321p.); 22cm. - Inscribed "Caledonian Literary Society." 2.A GENTLEMAN in the north of Scotland. 3S.SCOTLAND - Description and travel I BURTON, Henry, 1578-1648 K 140 The bateing of the Popes bull] / [by HenRy Burton], - [London?], [ 164-?]. -

Calvin Theological Seminary Covenant In

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SANG HYUCK AHN GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2011 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan. 49546-4301 800388-6034 Jax: 616957-8621 [email protected] www.calvinserninary.edu This dissertation entitled COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER written by SANG HYUCK AHN and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation ofthe undersigned readers: Carl R Trueman, Ph.D. David M. Rylaarsda h.D. Date Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Copyright © 2011 by Sang Hyuck Ahn All rights reserved To my Lord, the Head of the Church Soli Deo Gloria! CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I. Statement of the Thesis 1 II. Statement of the Problem 2 III. Survey of Scholarship 6 IV. Sources and Outline 10 CHAPTER 2. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE RUTHERFORD-HOOKER DISPUTE ABOUT CHURCH COVENANT 15 I. The Church Covenant in New England 15 1. Definitions 15 1) Church Covenant as a Document 15 2) Church Covenant as a Ceremony 20 3) Church Covenant as a Doctrine 22 2. Secondary Scholarship on the Church Covenant 24 II. Thomas Hooker and New England Congregationalism 31 1. A Short Biography 31 2. Thomas Hooker’s Life and His Congregationalism 33 1) The England Period, 1586-1630 33 2) The Holland Period, 1630-1633: Paget, Forbes, and Ames 34 3) The New England Period, 1633-1647 37 III. -

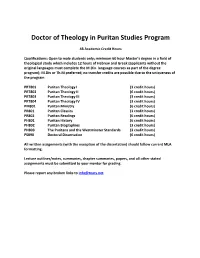

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

Title Page R.J. Pederson

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22159 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Pederson, Randall James Title: Unity in diversity : English puritans and the puritan reformation, 1603-1689 Issue Date: 2013-11-07 UNITY IN DIVERSITY: ENGLISH PURITANS AND THE PURITAN REFORMATION 1603-1689 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. Carel Stolker volgens besluit van het College voor promoties te verdedigen op 7 November 2013 klokke 15:00 uur door Randall James Pederson geboren te Everett, Washington, USA in 1975 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. dr. Gijsbert van den Brink Prof. dr. Richard Alfred Muller, Calvin Theological Seminary, Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA Leden: Prof. dr. Ernestine van der Wall Dr. Jan Wim Buisman Prof. dr. Henk van den Belt Prof. dr. Willem op’t Hof Dr. Willem van Vlastuin Contents Part I: Historical Method and Background Chapter One: Historiographical Introduction, Methodology, Hypothesis, and Structure ............. 1 1.1 Another Book on English Puritanism? Historiographical Justification .................. 1 1.2 Methodology, Hypothesis, and Structure ...................................................................... 20 1.2.1 Narrative and Metanarrative .............................................................................. 25 1.2.2 Structure ................................................................................................................... 31 1.3 Summary ................................................................................................................................ -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

RTS-ORLANDO: 25 YEARS and COUNTING Dr

FALL 2013 www.rts.edu RTS-ORLANDO: 25 YEARS and COUNTING Dr. Luder Whitlock and Dr. Don Sweeting mark a historic milestone. Steven Lawson's One Passion 10 • RTS and The Gospel Coalition 16 Introducing Dr. Ligon Duncan Editor’s Note: Just before this issue went During those 23 years as an RTS pro- to print, RTS named a new chancellor fessor, Dr. Duncan has lectured on many and CEO. A more detailed introduction campuses, as well as in Vienna and will be published in the Winter issue. Hong Kong. As an RTS faculty member he has spoken and delivered papers at he RTS Board of Trustees is various universities, seminaries and na- pleased to announce that Dr. Li- tional meetings, and has preached at or gon Duncan, a pastor-theologian addressed major conferences. His wife, with a long connection to the Anne, also has a strong RTS connec- seminary, has been elected as the new tion, having earned a master’s degree in chancellor and CEO of RTS. marriage and family therapy (they are Dr. Duncan is currently the John E. the parents of two teenagers and plan to Richards professor of systematic and continue to live in Jackson). historical theology at RTS-Jackson and Dr. Duncan’s pastoral experience be- has been senior minister at the historic gan in the 1980s in St. Louis and con- First Presbyterian Church in Jackson tinued in Britain where he preached in for the past 17 years. Dr. Duncan will various pulpits while doing his doctor- continue to teach systematic and his- al work at the University of Edinburgh torical theology for RTS, and remains in Scotland. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The life of Robert Woodford, 1606–1654 A biographical sketch of Robert Woodford is just that. Lacking a powerful patron or connections he was an obscure provincial who left a faint trail in official sources, no private correspondence, and no will. The only significant primary materials from which to construct his life (bar the diary) are the autobiographical essays produced by his son, the religious poet Dr Samuel Woodford FRS (1636–1700).1 The diarist was born at 11 a.m. on Thursday 3 April 1606 at Old, a village eight miles north of Northampton, and was baptized the following Sunday, the only child of Robert (1562–1636) and Jane Woodford ( fl. 1583–1641).2 His father, a modest farmer, had made a socially beneficial marriage to Jane Dexter, the daughter of Thomas Dexter, lord of Knightley’s Manor, and his wife Ann (nee´ Kinsman). Robert and Jane had been married at neighbouring Draughton on 2 May 1603.3 It is tempting to attach religious significance to this decision to marry outside the parish: the rector of Old was the obscure Alexander Ibbs, while the rector of Draughton was Thomas Baxter, a man with contacts in the defunct Kettering classis who was presented to the Church courts a year after the wedding accused of refusing to wear the 1Samuel Woodford left three autobiographical fragments. The first covers the period until 1662 and is printed in L.A. Ferrell, ‘An imperfect diary of a life: the 1662 diary of Samuel Woodforde’, Yale University Library Gazette, 63 (1989), pp. 137–144. -

Judaizing and Singularity in England, 1618-1667

Judaizing and Singularity in England, 1618-1667 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aidan Francis Cottrell-Boyce, Gonville and Caius College, June 2018. For Anna. Abstract In the seventeenth century, in England, a remarkable number of small, religious movements began adopting demonstratively Jewish ritual practices. They were labelled by their contemporaries as Judaizers. Typically, this phenomenon has been explained with reference to other tropes of Puritan practical divinity. It has been claimed that Judaizing was a form of Biblicism or a form of millenarianism. In this thesis, I contend that Judaizing was an expression of another aspect of the Puritan experience: the need to be recognized as a ‘singular,’ positively- distinctive, separated minority. Contents Introduction 1 Singularity and Puritanism 57 Judaizing and Singularity 99 ‘A Jewish Faccion’: Anti-legalism, Judaizing and the Traskites 120 Thomas Totney, Judaizing and England’s Exodus 162 The Tillamites, Judaizing and the ‘Gospel Work of Separation’ 201 Conclusion 242 Introduction During the first decades of the seventeenth century in England, a remarkable number of small religious groups began to adopt elements of Jewish ceremonial law. In London, in South Wales, in the Chilterns and the Cotswolds, congregations revived the observation of the Saturday Sabbath.1 Thomas Woolsey, imprisoned for separatism, wrote to his co-religionists in Amsterdam to ‘prove it unlawful to eat blood and things strangled.’2 John Traske and his followers began to celebrate Passover