Estimates for Worldwide Laboratory Animal Use in 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research in Primates Non-Human of Use The

The use of non-human primates in research The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatherall FRS FMedSci Report sponsored by: Academy of Medical Sciences Medical Research Council The Royal Society Wellcome Trust 10 Carlton House Terrace 20 Park Crescent 6-9 Carlton House Terrace 215 Euston Road London, SW1Y 5AH London, W1B 1AL London, SW1Y 5AG London, NW1 2BE December 2006 December Tel: +44(0)20 7969 5288 Tel: +44(0)20 7636 5422 Tel: +44(0)20 7451 2590 Tel: +44(0)20 7611 8888 Fax: +44(0)20 7969 5298 Fax: +44(0)20 7436 6179 Fax: +44(0)20 7451 2692 Fax: +44(0)20 7611 8545 Email: E-mail: E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.acmedsci.ac.uk Web: www.mrc.ac.uk Web: www.royalsoc.ac.uk Web: www.wellcome.ac.uk December 2006 The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatheall FRS FMedSci December 2006 Sponsors’ statement The use of non-human primates continues to be one the most contentious areas of biological and medical research. The publication of this independent report into the scientific basis for the past, current and future role of non-human primates in research is both a necessary and timely contribution to the debate. We emphasise that members of the working group have worked independently of the four sponsoring organisations. Our organisations did not provide input into the report’s content, conclusions or recommendations. -

Reporting the Implementation of the Three Rs in European Primate and Mouse Research Papers: Are We Making Progress?

ATLA 38, 495–517, 2010 495 Reporting the Implementation of the Three Rs in European Primate and Mouse Research Papers: Are We Making Progress? Katy Taylor British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, London, UK Summary — It is now more than 20 years since both Council of Europe Convention ETS123 and EU Directive 86/609?EEC were introduced, to promote the implementation of the Three Rs in animal experi- mentation and to provide guidance on animal housing and care. It might therefore be expected that reports of the implementation of the Three Rs in animal research papers would have increased during this period. In order to test this hypothesis, a literature survey of animal-based research was conducted. A ran- domly-selected sample from 16 high-profile medical journals, of original research papers arising from European institutions that featured experiments which involved either mice or primates, were identified for the years 1986 and 2006 (Total sample = 250 papers). Each paper was scored out of 10 for the incidence of reporting on the implementation of Three Rs-related factors corresponding to Replacement (justification of non-use of non-animal methods), Reduction (statistical analysis of the number of animals needed) and Refinement (housing aspects, i.e. increased cage size, social housing, enrichment of cage environment and food; and procedural aspects, i.e. the use of anaesthesia, analgesia, humane endpoints, and training for procedures with positive reinforcement). There was no significant increase in overall reporting score over time, for either mouse or primate research. By 2006, mouse research papers scored an average of 0 out of a possible 10, and primate research papers scored an average of 1.5. -

Harnessing Opportunities in Non-Animal Asthma Research for a 21St-Century Science

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 11-2011 Harnessing Opportunities in Non-Animal Asthma Research for a 21st-Century Science Gemma L. Buckland Humane Society International Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_arte Part of the Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons, Laboratory and Basic Science Research Commons, and the Research Methods in Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Buckland, G. L. (2011). Harnessing opportunities in non-animal asthma research for a 21st-century science. Drug discovery today, 16(21), 914-927. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harnessing opportunities in non-animal asthma research for a 21st-century science Gemma L. Buckland, Humane Society International CITATION Buckland, G. L. (2011). Harnessing opportunities in non-animal asthma research for a 21st-century science. Drug discovery today, 16(21), 914-927. ABSTRACT The incidence of asthma is on the increase and calls for research are growing, yet asthma is a disease that scientists are still trying to come to grips with. Asthma research has relied heavily on animal use; however, in light of increasingly robust in vitro and computational models and the need to more fully incorporate the ‘Three Rs’ principles of Replacement, Reduction and Refinement, is it time to reassess the asthma research paradigm? Progress in non-animal research techniques is reaching a level where commitment and integration are necessary. Many scientists believe that progress in this field rests on linking disciplines to make research directly translatable from the bench to the clinic; a ‘21st-century’ scientific approach to address age-old questions. -

Animal Experimentation in India

Animal Defenders International ● National Anti-Vivisection Society Animal Experimentation in India Unfettered science: How lack of accountability and control has led to animal abuse and poor science “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated. Vivisection is the blackest of all the black crimes that man is at present committing against God and His fair creation. It ill becomes us to invoke in our daily prayers the blessings of God, the Compassionate, if we in turn will not practise elementary compassion towards our fellow creatures.” And, “I abhor vivisection with my whole soul. All the scientific discoveries stained with the innocent blood I count as of no consequence.” Mahatma Gandhi Thanks With thanks to Maneka Gandhi and the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA) of India for their report on the use of animals in laboratories, which has been used for this critique of the state of scientific and medical research in India. Animal Defenders International and the National Anti-Vivisection Society UK fully support and encourage the efforts of the members of India’s CPCSEA to enforce standards and controls over the use of animals in laboratories in India, and their recommendation that facilities and practices in India’s research laboratories be brought up to international standards of good laboratory practice, good animal welfare, and good science. Contributors Jan Creamer Tim Phillips Chris Brock Robert Martin ©2003 Animal Defenders International & National Anti-Vivisection Society ISBN: Animal Defenders International 261 Goldhawk Road, London W12 9PE, UK tel. -

Laboratory Animals and the Art of Empathy D Thomas

197 RESEARCH ETHICS J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.2003.006387 on 30 March 2005. Downloaded from Laboratory animals and the art of empathy D Thomas ............................................................................................................................... J Med Ethics 2005;31:197–204. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.006387 Consistency is the hallmark of a coherent ethical take a big leap of imagination to empathise with the victims of animal experiments as well. In philosophy. When considering the morality of particular short: if we would not want done to ourselves behaviour, one should look to identify comparable what we do to laboratory animals, we should not situations and test one’s approach to the former against do it to them. one’s approach to the latter. The obvious comparator for Animals suffer animal experiments is non-consensual experiments on Crucially for the debate about the morality of people. In both cases, suffering and perhaps death is animal experiments, non-human animals suffer knowingly caused to the victim, the intended beneficiary is just as human ones do. Descartes may have described animals as ‘‘these mechanical robots someone else, and the victim does not consent. Animals [who] could give such a realistic illusion of suffer just as people do. As we condemn non-consensual agony’’ (my emphasis) but no serious scientist experiments on people, we should, if we are to be today doubts that the manifestation of agony is real, not illusory. Indeed, the whole pro-vivisec- consistent, condemn non-consensual experiments on tion case is based on the premise that animals animals. The alleged differences between the two practices are sufficiently similar to us physiologically, and often put forward do not stand up to scrutiny. -

APVMA Comments on Animal Welfare Policy

APVMA Comments on animal welfare policy Dangers of relying on animal experiments to determine human reactions. It has already been widely acknowledged that extrapolation from animals to humans can and does result in dangerously misleading outcomes. Species differences occur in respect of anatomy, the structure and function of organs, metabolism of toxins, rates of detoxification and protein binding, absorption of chemicals, mechanisms of DNA repair and lifespan, and more. So if such differences can occur between similar species then it’s negligent to extrapolate from say a rat to a human – two totally different species with a totally different genetic make-up. Another major difference is in the regulation of our genes. A mouse and a human for example, may share 99% of the same genes, however they are regulated differently. Both a mouse and a human have the same gene that enables us to grow a tail. In the case of a mouse that gene is “turned on”, but in humans that gene is “turned off.” The argument that we share a large proportion of genes with another species cannot therefore be used as a reason for selecting a particular animal model to predict human responses. Researchers often claim that animals are used because they need to test in a living system rather than on isolated cells or tissue, however an entire living system creates more variables which can further affect the outcome of any results. A point of interest is that most animal models used in toxicity testing have never been formally validated.1 Regulatory bodies often argue that alternative non-animal tests cannot be relied upon due to them not having been validated. -

The Failure of the Three R's and the Future of Animal Experimentation

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2006 | Issue 1 Article 7 Reduce, Refine, Replace: The aiF lure of the Three R's and the Future of Animal Experimentation Darian M. Ibrahim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Recommended Citation Ibrahim, Darian M. () "Reduce, Refine, Replace: The aiF lure of the Three R's and the Future of Animal Experimentation," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2006: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2006/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reduce, Refine, Replace: The Failure of the Three R's and the Future of Animal Experimentation DarianM Ibrahimt The debate in animal ethics is defined by those who advocate the regulation of animal use and those who advocate its aboli- tion.' The animal welfare approach, which focuses on regulating animal use, maintains that humans have an obligation to treat animals "humanely" but may use them for human purposes.2 The animal rights approach, which focuses on abolishing animal use, argues that animals have inherent moral value that is inconsis- tent with us treating them as property.3 The animal welfare approach is the dominant model of ani- mal advocacy in the United States.4 Animal experimentation provides a fertile ground for testing this model because a unique confluence of factors make experimentation appear susceptible to meaningful regulation. -

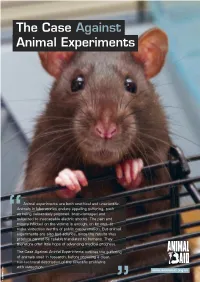

The Case Against Animal Experiments

The Case Against Animal Experiments Animal experiments are both unethical and unscientific. Animals in laboratories endure appalling suffering, such as being deliberately poisoned, brain-damaged and subjected to inescapable electric shocks. The pain and misery inflicted on the victims is enough, on its own, to make vivisection worthy of public condemnation. But animal “ “ experiments are also bad science, since the results they produce cannot be reliably translated to humans. They therefore offer little hope of advancing medical progress. The Case Against Animal Experiments outlines the suffering of animals used in research, before providing a clear, non-technical description of the scientific problems S E with vivisection. L I www.animalaid.org.uk C I N I M O D © How animals are used Contents Each year around four million How animals are used .......................... 1 animals are experimented on inside British laboratories. The suffering of animals in Dogs, cats, horses, monkeys, laboratories ........................................ 2 rats, rabbits and other animals Cruel experiments .................................... 2 are used, as well as hundreds A failing inspection regime ........................ 3 of thousands of genetically Secrecy and misinformation ...................... 4 modified mice. The most The GM mouse myth ................................ 4 common types of experiment The scientific case against either attempt to test how animal experiments .............................. 5 safe a substance is (toxicity Summary ............................................... -

Speciesism: a Form of Bigotry Or a Justified View? Evelyn Pluhar

-------~------------ - SPECIESISM: A FORM OF BIGOTRY OR A JUSTIFIED VIEW? EVELYN PLUHAR Pennsylvania State UniversityUniversity Fayette Campuscampus Editor's Note: An abridgedabridged version of this paper and thethe commentary on it by Prof.Prof. Sapontzis were delivered atat the December, 1987, meetingmeeting of the Society for the StudyStudy of Ethics and Animals held inin New York City.City. g~;~~~:Fr:iiil~~JmoDs. He ..... York: Dover, 1979 We humans tend to view ourselves as the paradigms of morally considerable beings. Humans, it is often claimed, are the most morally valuable (perhaps the ~ morally PHILOSOPHY valuable) beings on this planet. It is commonly assumed that "lesser" beings 83 BRIWEENBEIWEEN THE SPECIES should be sacrificed for our benefit. When For those who continue to think that it is not pressed to provide a rational defense for the wrong to eat and vivisect non humans, but belief in human pre-eminence, philosophers indefensible to do so to even less well have argued that our autonomous, richly mentally endowed humans, the issue should complex lives warrant our special status. be very pressing indeed. They stand accused Few, however, have argued that humans who of moral inconsistency by two very are incapable of autonomy may properly be different groups. Those who have become sacrificed to further the interests of normal convinced that moral considerability is not humans. restricted to humanity are urging that we cease even the painless exploitation of It was inevitable that this prima facie non humans. According to quite another, inconsistency would be challenged. Writers very disturbing view, we should consider like Peter Singer and Tom Regan advanced exploiting mentally defective humans in the argument from marginal cases to show addition to nonhumans. -

From Guinea Pig to Computer Mouse

International Network for Humane Education from guinea pig to computer mouse alternative methods for a progressive, humane education Nick Jukes Mihnea Chiuia InterNICHE Foreword by Gill Langley Second edition, revised and expanded B from guinea pig to computer mouse alternative methods for a progressive, humane education alternative methods for a progressive, humane education 22nd editionedition Nick Jukes, BSc MihneaNick Jukes, Chiuia, BSc MD Mihnea Chiuia, MD InterNICHE B The views expressed within this book are not necessarily those of the funding organisations, nor of all the contributors Cover image (from left to right): self-experimentation physiology practical, using Biopac apparatus (Lund University, Sweden); student-assisted beneficial surgery on a canine patient (Murdoch University, Australia); virtual physiology practical, using SimMuscle software (University of Marburg, Germany) 2nd edition Published by the International Network for Humane Education (InterNICHE) InterNICHE 2003- 2006 © Minor revisions made February 2006 InterNICHE 42 South Knighton Road Leicester LE2 3LP England tel/ fax: +44 116 210 9652 e-mail: [email protected] www.interniche.org Design by CDC (www.designforcharities.org) Printed in England by Biddles Ltd. (www.biddles.co.uk) Printed on 100% post-consumer recycled paper: Millstream 300gsm (cover), Evolve 80gsm (text) ISBN: 1-904422-00-4 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library B iv Contributors Jonathan Balcombe, PhD Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), USA Hans A. Braun, PhD Institute of Physiology, University of Marburg, Germany Gary R. Johnston, DVM, MS Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine, USA Shirley D. Johnston, DVM, PhD Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine, USA Amarendhra M. -

Action to End Animal Toxicity Testing

TH E WA Y FO R W A R D ACTION TO END ANIMAL TOXICITY TESTING REPORT COMPILED FOR THE BUAV BY The British Union for the European Coalition to DR GILL LANGLEY MA, PhD (CANTAB), MIBiol, CBiol Abolition of Vivisection End Animal Experiments Fo r e w o r d INTRODUCING THE EUROPEAN COALITION AND THE BUAV ACTION TO END ANIMAL TOXICITY TESTING The European Coalition to End Animal Experiments, (hereafter ‘the European Animal based toxicity tests cause massive suffering and are of dubious scientific Coalition’), is Europe’s leading alliance of animal protection organisations who have value; their credibility is based on established use rather than reliability or predictive come together to campaign for effective and long-lasting change for laboratory value.i animals. Formed in 1990 by animal groups across Europe, the Coalition now represents members across member states of the European Union plus a range of Testing programmes (such as the one proposed in the European Commission’s White international observer groups drawing together organisations with a range of Paper on a Future Chemicals Policy) could drastically increase the number of animals legislative, scientific and political expertise. Its membership base is currently used in toxicity experiments, or – with sufficient political will – can be used as an expanding to include those member groups in EU accession countries. Current opportunity to bring non-animal tests into use. Observer/Member groups of the European Coalition are as follows: This report demonstrates that animal tests can be replaced with modern, humane Members: ADDA (Spain); Animal Rights Sweden; Animalia (Finland); BUAV (UK); alternatives. -

Campaigns and Communications Assistant

Campaigns and Communications Assistant Job description and person specification Cruelty Free International is the leading organisation working to create a world where nobody wants or believes we need to experiment on animals. Our dedicated team are experts in their fields, combining award-winning campaigning, political lobbying, pioneering undercover investigations, scientific and legal expertise and corporate responsibility. Educating, challenging and inspiring others across the globe to respect and protect animals, we investigate and expose the reality of life for animals in laboratories, challenge decision-makers to make a positive difference for animals, and champion better science and cruelty free living. We are widely respected as an authority on animal testing issues and are frequently called on by governments, the media, corporations and official bodies for advice or expert opinion. We work professionally, building relationships with politicians, business leaders and officials, analysing legislation and challenging decision-making panels around the globe to act as the voice for animals in laboratories. With a history spanning over 100 years, Cruelty Free International has achieved so much for animals. Bringing the issue to public attention with our dynamic and determined approach, we have inspired generations of politicians, decision-makers and compassionate people to make a difference for animals used in experiments. As the problem has grown, we have stepped up to meet the challenge across the world, placing the issue on the global agenda for the first time. We have saved many thousands of animals from a life of suffering in laboratories, and together we can do so much more. Established in 1898, Cruelty Free International is firmly rooted in the early social justice movement.