5 Dutch Political Instagram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

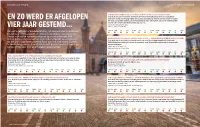

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

Het Eindverslag Downloaden

(On)zichtbare invloed verslag parlementaire ondervragingscommissie naar ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen 35 228 Parlementaire ondervraging ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen Nr. 4 BRIEF VAN DE PARLEMENTAIRE ONDERVRAGINGSCOMMISSIE Aan de Voorzitter van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal Den Haag, 25 juni 2020 De Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen (POCOB), biedt u hierbij het verslag «(On)zichtbare invloed» aan van de parlementaire ondervraging die zij op grond van de haar op 2 juli 2019 gegeven opdracht (Kamerstuk 35 228, nr. 1) heeft uitgevoerd. De verslagen van de verhoren die onder ede hebben plaatsgevonden, zijn als bijlage toegevoegd.1 De voorzitter van de commissie, Rog De griffier van de commissie, Sjerp 1 Kamerstuk II 2019/20, 35 228, nr. 5. pagina 1 /238 pagina 2 /238 De leden van de de Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen parlementaire in de Enquêtezaal op 6 februari 2020 van links naar rechts: R.A.J. Schonis, T. Kuzu, C.N. van den Berge, G.J.M. Segers , A. de Vries , M.R.J. Rog, C. Stoffer, E. Mulder (op 4 juni 2020 door de Kamer ontslag verleend uit de commissie) en A.A.G.M. van Raak. De leden en s taf van de de Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen parlementaire in de Enquêtezaal op 6 februari 2020 van links naar rechts: H.M. Naaijen, M.I.L. Gijsberts, R.A.J. Schonis, T. Kuzu, M.E.W. Verhoeven, C.N. van den Berge, L.K. Mi ddel hov en, G.J.M. Segers , E.M. Sj erp, W.J. -

JLP 16-4 Intro RW-MK Pre-Pub

Right-Wing Populism in Europe & USA: Contesting Politics & Discourse beyond ‘OrbAnism’ and ‘Trumpism’ Ruth Wodak and Michał Krzyżanowski Lancaster University / University of Liverpool 1. (Right-Wing) Populism Old & New: ShAred Ontologies, Recurrent PrActices Through a number of theoretical and empirical contriButions, this Special Issue of the Journal of Language and Politics addresses the recent sudden upsurge of right-wing populist parties (RWPs) in Europe and the USA. It responds to many recent challenges and a variety of ‘discursive shifts’ (Krzyżanowski 2013a, 2018 a,B) and wider dynamics of media and puBlic discourses that have taken place as a result of the upswing of right- wing populism (RWP) across Europe and Beyond (e.g., Feldman and Jackson 2013; Muller 2016; Wodak et al. 2013; Wodak 2013 a,b, 2015 a, 2016, 2017). The papers in the Special Issue cover institutionalised (individual and group) varieties of right-wing populist politics and also transcend a narrowly conceived political realm. Moreover, we investigate the ontology of the current surge of RWP, its state-of-the-art as well and, most importantly, how right-wing populist agendas spread, Become increasingly mediatised and thereBy ‘normalised’ in European and US politics, media and in the wider puBlic spheres (e.g., Wodak 2015 a,B; Link 2014). Indeed, in recent years and months new information about the rise of RWP has dominated the news practically every day. New polls about the possiBle success of such political parties have progressively caused an election scare among mainstream institutions and politicians. The unpredictaBle and unpredicted successes of populists (e.g. Donald Trump in the USA in 2016) have By now transformed anxieties into legitimate apprehension and fear. -

Tussen Onafhankelijkheid

Inhoudsopgave WOORD VOORAF IX 1 KABINETSFORMATIE 2017: EEN PROCEDURELE RECONSTRUCTIE 1 Verkiezingen en verkenning Schippers 3 Informatie-Schippers I 8 Informatie-Schippers II 12 Informatie-Tjeenk Willink 16 Informatie-Zalm 22 Formatie-Rutte 32 2 DE FASE VOORAFGAAND AAN HET KAMERDEBAT OVER VERKIEZINGSUITSLAG EN KABINETSFORMATIE 37 De gang van zaken in 2012 37 De gang van zaken in 2017 38 Beoordeling betrokkenen 39 Analyse en conclusies 40 Aanbevelingen 42 3 BESLUITVORMING IN DE TWEEDE KAMER OVER DE AANWIJZING VAN DE (IN)FORMATEUR 43 Gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2012 43 Gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2017 44 Beoordeling betrokkenen 47 Analyse en conclusie 48 Aanbevelingen 49 4 POSITIE EN WERKWIJZE VAN VERKENNER EN INFORMATEUR 51 Gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2012 51 Gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2017 51 Beoordeling betrokkenen 56 Analyse en conclusie: de werkwijze van de informateur 58 Analyse en conclusie: de positie van de informateur 59 Aanbeveling 60 5 HET VERSTREKKEN VAN INLICHTINGEN AAN DE TWEEDE KAMER TIJDENS DE KABINETSFORMATIE 61 De praktijk vóór 2017 62 De gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2017 64 Beoordeling betrokkenen 68 vi Inhoudsopgave ――― Analyse en conclusies 70 Aanbevelingen 75 6 DE TWEEDE KAMERVOORZITTER EN DE KABINETSFORMATIE 77 Gang van zaken kabinetsformatie 2012 77 Gang van zaken kabinetsformatie 2017 78 Beoordeling betrokkenen 79 Analyse en conclusies 80 Aanbevelingen 82 7 DE POSITIE VAN DE KONING BIJ DE KABINETSFORMATIE 83 Gang van zaken bij de kabinetsformatie 2012 83 Gang -

Erop of Eronder

TRIBUNENieuwsblad van de SP • jaargang 56 • nr. 9 • oktober 2020 • € 1,75 • www.sp.nl KERMIS EROP OF ERONDER NERTSENFOKKERS MAKEN HET BONT REFERENDUM DICHTERBIJ STEM VOOR DE KOOLMEESCUP Wéér dreigen pensioenkortingen en premiestijgingen. Maar de pensioen- bestuurders graaien lekker door uit de pensioenpot. Stemt u mee op een van deze grootverdieners? De ‘winnaar’ krijgt de Koolmeescup, genoemd naar de D66-minister die het allemaal maar toelaat. doemee.sp.nl/pensioengraaiers BEN JIJ EEN JONGE SP’ER, MAAR GEEN ROOD-LID? SLUIT JE NU GRATIS AAN EN STEUN DE MEEST ACTIEVE POLITIEKE JONGEREN ORGANISATIE VAN NEDERLAND! KOM BIJ HET LEDENTEAM! ROOD zoekt enthousiaste, praatgrage en behulpzame ROOD-leden voor het nieuwe Ledenteam. Dat zal vragen van (nieuwe) leden gaan Wil jij in het Ledenteam beantwoorden, zoals: wat doet ROOD; hoe en waar kan ik actief om de organisatie van worden; hoe draai ik mee in de SP en waar ga ik naartoe met mijn ideeën? We hopen met het Ledenteam een communicatie-snelweg ROOD te versterken? te creëren. Ook kan het Ledenteam ledenonderzoeken opzetten en een grote rol gaan spelen bij het verstrekken van informatie bij campagnes en acties. Uiteraard bieden we daarbij ondersteuning vanuit het bestuur, we willen bijvoorbeeld investeren in Ledenteam- Stuur dan jouw motivatie telefoons. Zo kunnen ook leden die graag actief willen worden maar naar [email protected] bijvoorbeeld geen ROOD-groep in de buurt hebben, zich inzetten voor ROOD. DE SP ZET ZICH IN VOOR MENSELIJKE WAARDIGHEID, GELIJKWAARDIGHEID EN SOLIDARITEIT TRIBUNE IS EEN Redactie -

Prinsjesdagpeiling 2017

Rapport PRINSJESDAGPEILING 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug 14 september 2017 www.ioresearch.nl I&O Research Prinsjesdagpeiling september 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug Als er vandaag verkiezingen voor de Tweede Kamer zouden worden gehouden, is de VVD opnieuw de grootste partij met 30 zetels. Opvallend is de verschuiving aan de rechterflank. De PVV verliest drie zetels ten opzichte van de peiling in juni en is daarmee terug op haar huidige zetelaantal (20). Forum voor Democratie stijgt, na de verdubbeling in juni, door tot 9 zetels nu. Verder zijn er geen opvallende verschuivingen in vergelijking met drie maanden geleden. Zes op de tien Nederlanders voor ruimere bevoegdheden inlichtingendiensten Begin september werd bekend dat een raadgevend referendum over de ‘aftapwet’ een stap dichterbij is gekomen. Met deze wet krijgen Nederlandse inlichtingendiensten meer mogelijkheden om gegevens van internet te verzamelen, bijvoorbeeld om terroristen op te sporen. Tegenstanders vrezen dat ook gegevens van onschuldige burgers worden verzameld en bewaard. Hoewel het dus nog niet zeker is of het referendum doorgaat, heeft I&O Research gepeild wat Nederlanders nu zouden stemmen. Van de kiezers die (waarschijnlijk) gaan stemmen, zijn zes op de tien vóór ruimere bevoegdheden van de inlichtingendiensten. Een kwart staat hier negatief tegenover. Een op de zes kiezers weet het nog niet. 65-plussers zijn het vaakst voorstander (71 procent), terwijl jongeren tot 34 jaar duidelijk verdeeld zijn. Kiezers van VVD, PVV en de christelijke partijen CU, SGP en CDA zijn in ruime meerderheid voorstander van de nieuwe wet. Degenen die bij de verkiezingen in maart op GroenLinks en Forum voor Democratie stemden, zijn per saldo tegen. -

Tien Jaar Premier Mark Rutte

Rapport TIEN JAAR PREMIER MARK RUTTE In opdracht van Trouw 8 oktober 2020 www.ioresearch.nl Colofon Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2020/173 Datum oktober 2020 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits I&O Research en Trouw als bron duidelijk worden vermeld. Coronabeleid: Tien jaar premier Mark Rutte 2 van 38 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 5 1 Zetelpeiling en stemmotieven _______________________________________________________ 8 1.1 Zetelpeiling _____________________________________ 8 1.2 Stemmotieven algemeen ______________________________ 9 1.3 Stemmotieven VVD-kiezers: Rutte wérd de stemmentrekker _________ 10 1.4 Stemmen op Rutte? _________________________________ 11 1.5 Redenen om wel of niet op Mark Rutte te stemmen _______________ 12 2 Bekendheid en waardering politici __________________________________________________ 13 2.1 Bekendheid politici _________________________________ 13 2.2 Waardering politici _________________________________ 14 3 De afgelopen 10 jaar ________________________________________________________________ 15 3.1 Nederlandse burger beter af na 10 jaar Rutte? __________________ 15 3.2 Polarisatie toegenomen; solidariteit afgenomen ________________ 15 4 Premier Mark Rutte _________________________________________________________________ 17 4.1 Zes op tien vinden dat Rutte het goed heeft gedaan als premier ________ 17 4.2 Ruttes “grootste verdienste”: -

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD Net als velen van u zou ik nergens liever willen leven dan hier. Ons mooie land heeft een gigantisch potentieel. We zijn innovatief, nuchter, hardwer- kend, trots op wie we zijn en gezegend met een indrukwekkende geschie- denis en een gezonde handelsgeest. Een Nederland dat Nederland durft te zijn is tot ongekende prestaties in staat. Al sinds de komst van Pim Fortuyn in 2002 laten miljoenen kiezers weten dat het op de grote terreinen van misdaad, migratie, het functioneren van de publieke sector en Europa anders moet. Nederland zal in een uitdijend en oncontroleerbaar Europa meer voor zichzelf moeten kiezen en vertrouwen en macht moeten terugleggen bij de kiezer. Maar keer op keer krijgen rechtse kiezers geen waar voor hun stem. Wie rechts stemt krijgt daar immigratierecords, een steeds verder uitdijende overheid, stijgende lasten, een verstikkend ondernemersklimaat, afschaffing van het referendum en een onbetaalbaar en irrationeel klimaatbeleid voor terug die ten koste gaan van onze welvaart en ons woongenot. Ons programma is een realistische conservatief-liberale koers voor ieder- een die de schouders onder Nederland wil zetten. Positieve keuzes voor een welvarender, veiliger en herkenbaarder land waarin we criminaliteit keihard aanpakken, behouden wat ons bindt en macht terughalen uit Europa. Met een overheid die er voor de burgers is en goed weet wat ze wel, maar ook juist niet moet doen. Een land waarin we hart hebben voor wie niet kan, maar hard zullen zijn voor wie niet wil. Wij zijn er klaar voor. Samen met onze geweldige fracties in de Eerste Kamer, het Europees Parlement en de Amsterdamse gemeenteraad én met onze vertegenwoordigers in de Provinciale Staten zullen wij na 17 maart met grote trots ook uw stem in de Tweede Kamer gaan vertegenwoordigen. -

Factsheet: the Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1. At a glance The Netherlands is the main constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with its monarch King Willem-Alexander. Since 1848 it has been governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, organised as a unitary state. The Dutch Parliament "Staten-Generaal" is a bicameral body. It consists of two chambers, both of which are elected for four-year terms. The Senate, the Eerste Kamer is indirectly elected. It consists of 75 members and is elected by the (directly elected) members of the 12 provincial state councils, known as the "staten". The 150 members of the House of Representatives, the Tweede Kamer, are directly elected through a national party-list system, on the basis of proportional representation. On 26 October 2017 the third Cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte took office. Four political parties formed the governing coalition: People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats 66 (D66) and Christian Union (CU). On 15 January 2021 the government resigned over the child benefits affair. The government will stay on in caretaker capacity until general elections scheduled for 17 March 2021. 2. Composition Results of the parliamentary elections of 15 March 2017 and current redistribution of seats Party EP % Seats affiliation Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) 321 People's Party for Freedom and Democracy 21,3% (33) Partij Voor de Vrijheid (PVV) Party for Freedom 13,1% 20 Christen Democratisch Appèl (CDA) Christian Democratic Appeal 12,4% 19 Democraten 66 (D66) Democrats 66 12,2% 19 1 In 2019, Wybren van Haga, was expelled from the VVD. -

Canon DR-G1100 Serienr. 21GGJ01978

4 Model N 10-1 - Proces-verbaal van een stembureau 1 / 65 Model N 10-1 Proces-verbaal van een stembureau De verkiezing van de leden van Tweede Kamerverkiezing 2021 op woensdag 17 maart 2021 Gemeente Helmond Kieskring 18 Wa arom een proces-verbaal? Elk stembureau maakt bij een verkiezing een proces-verbaal op. Met het proces-verbaal legt het stembureau verantwoording af over het verloop van de stemming en over de telling van de stemmen. Op basis van de processen-verbaal wordt de uitslag van de verkiezing vastgesteld. Vul het proces-verbaal daarom altijd juist en volledig in. Na de stemming mogen kiezers het proces-verbaal inzien. Zo kunnen zij nagaan of de stemming en de telling van de stemmen correct verlopen zijn. Wie vullen het proces-verbaal in en ondertekenen het? Alle stembureauleden zijn verantwoordelijk voor het correct en volledig invullen van het proces-verbaal. Na afloop van de telling van de stemmen ondertekenen alle stembureauleden die op dat moment aanwezig zijn het proces-verbaal. Dat zijn in elk geval de voorzitter van het stembureau en minimaal twee andere stembureauleden. 1. Locatie en openingstijden stembureau A Als het stembureau een nummer heeft, vermeld dan het nummer 502 B Op welke datum vond de stemming plaats? Datum 17-03-2021 van O 1 3 I O tot 2 ±A 3 I O uur. C Waar vond de stemming plaats? Openingstijden voor kiezers Adres of omschrijving locatie van GEMEENSCHAPSHUIS DE LOOP, Peeleik 7, 5704 AP Helmond uur 07 l3o D Op welke datum vond de telling plaats? 2 \ Datum \~7 ' C> 3' van ^ | : ^IQ tot () I tl pl Q uur. -

Het Is Heel Menselijk Zich Iets Niet Te Herinneren

Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren Door J.M.C.M. Smarius - 10 april 2021 Geplaatst in Omtzigtdebat Opa, wat vond je van dat debat over ‘positie Omtzigt functie elders’? “Langdradig tweederangs circus met deelnemers aan de circusvoorstelling die uiteindelijk zichzelf vaak in de vingers snijden door de indruk achter te laten niet goed genoeg te zijn om mee te doen.” Hoezo? “Deelnemers die tot treurnis toe alsmaar herhalen dat iemand liegt, zonder ook maar een poging te doen tot aannemelijke onderbouwing van deze beschuldiging. En die het zich niet herinneren van iets meteen bestempelen als een bewijs dat iemand niet meer geschikt is voor een bepaalde taak, aldus blijk gevend van een volslagen onbegrip van het begrip zich herinneren.” Een hele mond vol. Wat bedoel je met onbegrip van het begrip zich herinneren? “Mensen hebben het vermogen herinneringen die ons kunnen afleiden selectief te vergeten. Ratten Wynia's week: Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren | 1 Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren hebben dat vermogen ook. Dat blijkt uit een studie van de University of Cambridge. De ontdekking dat ratten en mensen een gemeenschappelijk actief vermogen om te vergeten delen wijst erop dat dit vermogen een essentiële rol speelt in de aanpassing van zoogdieren aan hun leefomgeving, en dat het waarschijnlijk minstens teruggaat tot de tijd waarin de gemeenschappelijke voorouder van ratten en mensen leefde, zo’n 100 miljoen jaar geleden. Geschat wordt dat het menselijk brein 86 miljard neuronen of hersencellen bevat, en wel 150 biljoen synaptische verbindingen, wat van het brein een krachtige machine maakt om herinneringen te verwerken, op te slaan.