Irish Literature in Austria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Patrick's Recommended Reading List

St Patrick’s Recommended Reading list At St Patrick’s we want your children to be confident readers and more importantly enjoy reading! We have put together a list of books that we feel your child will enjoy and suitable for their reading level! Red, Yellow, Blue, Green and Orange bands (Working within Foundation stage or stage 1) Title Author Each Peach Pear Plum Janet and Allen Ahlberg Mr Gumpy’s Outing John Burningham Rosie’s Walk’ Pat Hutchins The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ Eric Carle Mister Magnolia’ Quentin Blake Owl Babies’ Martin Waddel Alfie Gets in First’ Shirley Hughes Elmer David McKee Brown Bear, Brown Bear what do you see? Bill Martin and Eric Carle We’re going on a bear hunt Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury My cat likes to hide in boxes’ Lynley Dodd ‘Peepo’ Janet and Allen Ahlberg Meg and Mog’ Helen Nicoll and Jan Pienkowski Dear Zoo’ Rod Campbell Kipper Mick Inkpen The Pig in the Pond’ Martin Waddell and Jill Barton Oh Dear!’ Rod Campbell Where’s Spot’ Eric Hill This is the Bear’ and ‘This is the Bear and Sarah Hayes and Helen Craig the Picnic Lunch’ Not Now Bernard’ David McKee Where the Wild Things Are’ Maurice Sendak Gorilla Anthony Browne A Dark, Dark Tale’ Ruth Brown 1 Turquoise, Purple, Gold and silver bands (Working within stages 2 or 3) Frog and Toad are Friends’ Arnold Lobel and other Frog and Toad stories Mrs Plug the Plumber’ and Allan Ahlberg other stories in this series Solomon’s Secret’ Saviour Pirotta Peace at last Jill Murphy The Tiger who came to tea’ Judith Kerr Hairy Maclary from Lynley Dodd Donoldson’s -

An Exploration of Pre-Censorship of Children’S Books: Perceptions and Experiences of Canadian Authors and Illustrators

AN EXPLORATION OF PRE-CENSORSHIP OF CHILDREN’S BOOKS: PERCEPTIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF CANADIAN AUTHORS AND ILLUSTRATORS by CHERIE LYNN GIVENS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Library, Archival and Information Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2009 © Cherie Lynn Givens, 2009 Abstract There is little documentation of pre-censorship of children’s literature. The discussion of pre-censorship is often submerged within more general censorship discussions and not specifically identified. It is addressed in snippets of information revealed in interviews and responses to questionnaires concerning censorship. This study was designed to examine in detail the phenomenon of pre-censorship as experienced by Canadian children’s and young adult authors and illustrators. A qualitative, naturalistic methodology was selected to explore participants’ experiences through in-depth interviews with open-ended questions designed to encourage participants to speak at length and share thoughts, feelings, and insights. Seventeen Canadian authors and illustrators, who self-identified as having experienced pre-censorship, participated in this study. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with all but one of the participants, whose interview was conducted by telephone and a follow-up in-person meeting. Most participants requested confidentiality, wishing to keep their names and the titles of the books undisclosed. Participants provided concrete examples of how pre-censorship was experienced by authors and illustrators. Types of pre-censorship were identified. Reasons given for pre- censorship make clear that marketing and sales concerns as well as a fear of censorship after publication are dominant motivating factors. -

An Leabharlann 6

An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY Second Series Volume 12 Number 4 1996 * Future of Northern Ireland's Public Libraries : A Symposium * Art Exhibition Catalogues * Libraries in Washington * Reviews * Recent Publications *News An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY ISSN 0023-9542 Second Series Volume 12 Number 4 1996 CON T ENTS P AGE Editorial 115 Art Exhibition Catalogues – a Resource for Art Documentation Olivia Fitzpatrick 117 Impressions of Library Services in King County, Washington Deirdre Ní Raghallaigh 123 Crossroads? A Symposium on the Future of Public Libraries in Northern Ireland Liam Parker, Gerry Burns, Kirby Porter, Anne Peoples, Beth Porter 129 Information Matters: News and Notes 145 Obituaries: Brighid Dolan, Mary Moore 155 Recent Publications 157 Reviews l William J Martin, The Global Information Society (Ian Cornelius) 164 l Hans Prins and William de Gier, The Image of the Library and Information Profession (Agnes Neligan) 165 l William Nolan, Liam Ronayne, Mairead Dunlevy, editors, Donegal History and Society (Nodlaig Hardiman) 166 l Jennifer MacDougall, Information for Health (Margaret Haines) 169 An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY Journal of the Library Association of Ireland and the Northern Ireland Branch of the Library Association Editors: Kevin Quinn and Fionnuala Hanrahan. Editorial Advisory Board: Jess Codd, Penny Holloway, Agnes Neligan. Prospective manuscripts for inclusion in the journal should be sent to: * Fionnuala Hanrahan, Dublin Corporation Library HQ, Cumberland House, Fenian Street, Dublin, 2, Republic of Ireland. Tel: +353 1 661 9000. Fax: +353 1 676 1628. E-Mail: [email protected] * Kevin Quinn, South Eastern Education and Library Board, Library HQ, Windmill Lane, Ballynahinch, Co. Down, Northern Ireland, BT24 8DH. -

5-Plagues-Reading-Spine

Mr A, Mr C and Mr D Present… Reading Reconsidered Reading Spine Text Selector for Primary Schools Contents The 5 Plagues of a Developing Reader p3 Creation of the List & p4 Application to Long Term Plans Years 1-2 List p5-8 Years 3-4 List p9-11 Years 5-6 List p12-16 Other Books to Consider p17-20 Other Resources p21 The 5 Plagues of the Developing Reader In his book ‘Reading Reconsidered’, Doug Lemov points out that there are five types of texts that children should have access to in order to successfully navigate reading with confidence. These are complex beyond a lexical level and demand more from the reader than other types of books. Read his blog article here: http://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/on-text-complexity-and-reading-part-1- the-five-plagues-of-the-developing-reader/ Archaic Language The vocabulary, usage, syntax and context for cultural reference of texts over 50 or 100 years old are vastly different and typically more complex than texts written today. Students need to be exposed to and develop proficiency with antiquated forms of expression to be able to hope to read James Madison, Frederick Douglass and Edmund Spenser when they get to college. Non-Linear Time Sequences In passages written exclusively for students—or more specifically for student assessments— time tends to unfold with consistency. A story is narrated in a given style with a given cadence and that cadence endures and remains consistent, but in the best books, books where every aspect of the narration is nuanced to create an exact image, time moves in fits and start. -

Hans Christian Andersen Awards Are the Highest International Distinction in Children’S Literature

HANS CH RISTIAN A NDERSEN A WARDS Christine E. King, Iowa State University The Hans Christian Andersen Awards are the highest international distinction in children’s literature. They are given every other year to a living author and illustrator whose outstanding body of work is judged to have made a lasting contribution to literature for children and young people. The first three awards were made to authors for single works. The author’s award has been given since 1956 and the illustrator’s since 1966. They are presented by the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). They have become the “Little Nobel Prize,” and their prestige has grown over the years. Selecting the award win- ners is considered by many to be IBBY’s most important activity. The nominations are made by the National Sections of IBBY, and the recipients are selected by a distinguished international jury of children’s literature specialists. The IBBY emphasizes that the Hans Christian Andersen Awards are not intended to be a national award, but an outstanding international award for chil- dren’s literature. A great effort is made to encourage the submission of candidates from all over the world, and a jury of ten experts is also selected from around the world in order to encourage a diversity of outlook and opinion. The award consists of a gold medal bearing the portrait of Hans Christian Andersen and a diploma and is presented at the opening ceremony of the IBBY Congress. The IBBY’s refereed journal Bookbird has a special Andersen Awards issue which presents all the nominees and documents the selection process. -

Sample Pre K Books for Tools of the Mind Classes

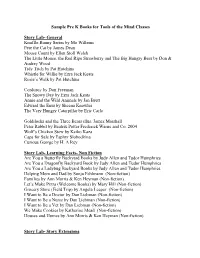

Sample Pre K Books for Tools of the Mind Classes Story Lab- General Knuffle Bunny Series by Mo Willems Pete the Cat by James Dean Mouse Count by Ellen Stoll Walsh The Little Mouse, the Red Ripe Strawberry and The Big Hungry Bear by Don & Audrey Wood Tidy Titch by Pat Hutchins Whistle for Willie by Ezra Jack Keats Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins Corduroy by Don Freeman The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats Annie and the Wild Animals by Jan Brett Edward the Emu by Sheena Knowles The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle Goldilocks and the Three Bears illus. James Marshall Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter Frederick Warne and Co. 2004 Wolf’s Chicken Stew by Keiko Kaza Caps for Sale by Esphyr Slobodkina Curious George by H. A Rey Story Lab- Learning Facts- Non Fiction Are You a Butterfly Backyard Books by Judy Allen and Tudor Humphries Are You a Dragonfly Backyard Book by Judy Allen and Tudor Humphries Are You a Ladybug Backyard Books by Judy Allen and Tudor Humphries Helping Mom and Dad by Sonja Fehlmann (Non-fiction) Families by Ann Morris & Ken Heyman (Non-fiction) Let’s Make Pizza (Welcome Books) by Mary Hill (Non-fiction) Grocery Store (Field Trip) by Angela Leeper (Non-fiction) I Want to Be a Doctor by Dan Liebman (Non-fiction) I Want to Be a Nurse by Dan Liebman (Non-fiction) I Want to Be a Vet by Dan Liebman (Non-fiction) We Make Cookies by Katherine Mead (Non-fiction) Houses and Homes by Ann Morris & Ken Heyman (Non-fiction) Story Lab- Story Extensions Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown I Went Walking by Sue Williams Edward the Emu by Sheena Knowles (as above) Brown Bear, Brown Bear by Bill Martin Jr. -

Books for Pre-K Through Grade 1

c01.qxd 11/25/03 5:03 PM Page 1 SECTION ONE Books for Pre-K Through Grade 1 1.1 Classics and All-Time Favorites Children submerged in a rich literary environment become better readers and writers as they grow. Younger children enjoy these favorites as read-alouds; older children enjoy hearing them over and over until they begin to read the books independently. Amelia Bedelia (series) by Peggy Parish Madeline (series) by Ludwig Bemelmans Are You My Mother? by P. D. Eastman Make Way for Ducklings by Robert McCloskey Arthur (series) by Marc Brown Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel by Barnyard Dance! by Sandra Boynton Virginia Lee Burton Blueberries for Sal by Robert McClosky Millions of Cats by Wanda Gag Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? by Dr. Seuss by Bill Martin Jr. Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters: An African Tale Caps for Sale by Esphyr Slobodkina by John Steptoe Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin Jr. The Napping House by Audrey Wood and John Archambault The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs by Judi The Runaway Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown Barrett The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats Copyright © 2004 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Corduroy (series) by Don Freeman The Story About Ping by Marjorie Flack Curious George (series) by H. A. Rey The Story of Babar, the Little Elephant (series) Eloise (series) by Hilary Knight by Jean de Brunhoff Fables by Arnold Lobel The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf Frances (series) by Russell Hoban The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter Frog and Toad (series) by Arnold Lobel Three Tales of My Father’s Dragon by Ruth George and Martha by James Marshall Stiles Gannett Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown Tikki Tikki Tembo by Arlene Mosel Green Eggs and Ham by Dr. -

Librarians' Favourite Books from Their Country

the world through picture books Librarians’ favourite books from their country A programme of Section Libraries for Children and Young Adults, IFLA – International Federation and Library Associations in collaboration with IFLA section Literacy and Reading and IBBY – International Board on Books for Young People. Programme coordination Annie Everall [email protected] in collaboration with Viviana Quiñones [email protected] The World through Picture Books, 2012 Edited by Annie Everall and Viviana Quiñones • Design by Ursula Held the throughworld picture books Foreword By Viviana Quiñones We are very happy to publish the first results of this participative, international, ongoing Chair, IFLA Section Libraries programme, “The World through Picture Books”. It deals with something we children’s for Children and Young Adults librarians must never lose sight of, even if we are so busy with new technologies, budget [email protected] restrictions, everyday work…: read children’s books and choose the best ones for our readers. Of course, we could spend hours discussing what “best” means, but one thing it surely means is very good books from the readers’ own country and from as many other countries as possible…This is why, inspired by Kazuko Yoda’s request to our Committee for advice on the “top ten” picture books in Committee members’ countries, we launched “The World through Picture Books” programme, in 2011. Librarians from thirty countries have already made their choice which we publish here, and, thanks to publishers’ generosity, their selected titles will be exhibited in Finland, before circulating in Japan; another set of books is available for any library in any country wanting to exhibit them. -

Roade English Hub Suggested Book Spine

Roade English Hub Suggested Book Spine Reception Owl Babies, Martin Waddell The Gruffalo, Julia Donaldson Handa’s Surprise, Eileen Browne (Walker Books) Mr Gumpy’s Outing, John Burningham (Bloomsbury) Rosie’s Walk, Pat Hutchins (Random House) Six Dinner Sid, Inga Moore (Hodder) Mrs Armitage, Quentin Blake Whatever Next, Jill Murphy (Macmillan) On the Way Home, Jill Murphy (Macmillan) Farmer Duck, Martin Waddell (Walker Books) Goodnight Moon, Margaret Wise Brown (HarperCollins) Shhh! Sally Grindley (Bloomsbury) Mr Wolf’s Pancakes, Jan Fearnley Oi Frog, Kes Gray and Jim Field Flotsam, David Wiesner Roade English Hub Suggested Book Spine Year 1 Peace at Last, Jill Murphy (Macmillan Can’t You Sleep Little Bear? Martin Waddell (Walker Books) Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak (HarperCollins) The Elephant and the Bad Baby, Elfrida Vipont and Raymond Briggs (Puffin) Avocado Baby, John Burningham (Bloomsbury The Tiger Who Came to Tea, Judith Kerr (HarperCollins) Lost and Found, Oliver Jeffers (HarperCollins) Knuffle Bunny, Mo Willems (Hyperion Books) Beegu, Alexis Deacon (Random House) Dogger, Shirley Hughes (Random House) Cops and Robbers, Alan and Janet Ahlberg (Puffin) Elmer, David McKee (Andersen Press) We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, Michael Rosen Funny Bones, Janet and Alan Ahlberg Roade English Hub Suggested Book Spine Year 2 Traction Man is Here, Mini Grey (Random House) Meerkat Mail, Emily Gravett (Macmillan) Wolves, Emily Gravett (Macmillan) Little Mouse’s Big Book of Fears, Emily Gravett (Macmillan). Amazing Grace, Mary Hoffman -

The Books Kids Will Sit Still for Handout

The Books Kids Will Sit Still For Handout A Closer Look at Some of the Top-Rated Children's Books of 2012 and 2013 for Grades PreK-6 Compiled and written by Judy Freeman (www.JudyReadsBooks.com) Fall, 2013 The following booklist are arranged into three chapters (Easy Fiction/Picture Books, then Fiction, then Nonfiction, which includes poetry and folklore), and are then in alphabetical order by title for easy access. The list contains some of the memorable, interesting, distinguished, and award-winning titles published in 2012 and 2013. All are books I believe every teacher and librarian should know and share, whether by reading aloud, booktalking, or using with children for Literature Circles, Guided or Shared Reading, Book Clubs, or Readers Advisory. Working on your Common Core Curriculum goals? These are all books worthy of inclusion into your curriculum, your story hour, and, yes, your life. Each book entry consists of five parts: 1. BIBLIOGRAPHIC INFO: Includes title, author, illustrator, publisher and date, ISBN (International Standard Book Number), number of pages, call number (E=Easy Fiction/Picture Book; FIC=Fiction; B=Biography; #=Nonfiction), and suggested grade level range, though that is never set in stone; picture books so often can, should, must be used well beyond their intended grade levels—what I call Picture Books for All Ages. 2. ANNOTATION: To help you remember what the book’s about; to lure you into reading it alone and/or aloud; and/or to provide a meaty review that you can also use as a booktalk. 3. GERM: A good practical, do-able, useful, pithy idea, activity, or suggestion of ways to use the book for reading, writing, illustrating prompts, and other activities across the curriculum, and for story hour programs, including creative drama, Reader’s Theater, storytelling, group discussion, booktalks, games, crafts, research, and problem-solving. -

Guided Reading Level List 2021

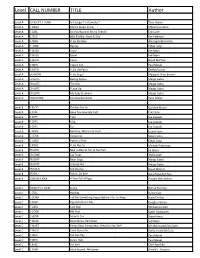

Level CALL NUMBER TITLE Author Level A CONCEPT E HOBA Is It Larger? Is It Smaller? Tana Hoban Level A E ANNO Anno's Magic Seeds Mitsumasa Anno Level A E CARL Do You Want to Be my Friend? Eric Carle Level A E FELD Billy & Milly, Short & Silly Eve Feldman Level A E FERR I Like My Bike Antongionata Ferrari Level A E LONG Big Cat Ethan Long Level A E MACK Look! Jeff Mack Level A E MACK Mine! Jeff Mack Level A E McPH Jump David McPhail Level A E MEIS I See A Cat Paul Meisel Level A E ROTN I Like the Farm Shelley Rotner Level A ER BROW I Like Bugs! Margaret Wise Brown Level A ER GATE Baking Apples Margo Gates Level A ER GATE The Fish Margo Gates Level A ER GATE I Look Up Margo Gates Level A ER GATE My Baby Elephant Margo Gates Level A J 624 HOBA Construction Zone Tana Hoban Level B E BLOO The Bus For Us Suzanne Bloom Level B E CARL Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle Level B E CEPE I See Joe Cepeda Level B E CEPE I Dig Joe Cepeda Level B E CEPE Up Joe Cepeda Level B E GORE Mommy, Where are You? Leonid Gore Level B E HENR Happy Cat Steve Henry Level B E LONG Pig has a Plan Ethan Long Level B E ROBE I Like My Car Michael Robertson Level B ER ATKI Ned in Bed; & Fun at the Park Jill Atkins Level B ER COXE Cat Traps Molly Coxe Level B ER GATE Bean Soup Margo Gates Level B ER GATE A Good Nut Margo Gates Level B ER MILG See Zip Zap David Milgrim Level B ER RAU Robot, Go Bot! Dana Meachen Rau Level B J 598.842 JENK A Nest Full of Eggs Priscilla Belz Jenkins Level C CONCEPT E FLEM Lunch Denise Fleming Level C E COLE Big Bug Henry Cole Level C E DUNB Tell -

Bird 40,#3-Focus IBBY

Focus IBBY Column Editor: Leena Maissen IBBY in Bologna 2002 One of the eagerly awaited moments in IBBY’s institutional life is the announcement of the Hans Christian Andersen Award winners, every two years, at two-thirty in the afternoon, during the first day of the Children’s Book Fair in Bologna. The meeting room in Hall 29, where the press conference is held, is too small, overcrowded, and hot, but there is no better alternative. Those who have not been lucky enough to get seats impatiently hope that the other presentations of IBBY activities will pass by quickly, never mind how important they might be. After all, they want to know who the winners are. This year, with Aidan Chambers and Quentin Blake, it was a double for Britain. The British IBBY Section would not believe the news that their candidates had won, since the 2000 illustrator award had gone to Anthony Browne. Their surprise and joy was overwhelming. It seems like a miracle that the jury and the winners—who are notified beforehand—can keep the results secret for two weeks— but they did. When Jury President Jay Heale disclosed the name of the winning author, Aidan Chambers emerged from the back of the room to the podium accompanied by a roar of applause. Although he was unable to attend the event personally, the announcement of Quentin Blake as the winning illustrator was greeted with equally enthusiastic approval. Toasts were raised to celebrate both winners during the traditional champagne and cookies reception at the IBBY stand afterwards. The works and dossiers of all the 55 authors and illustrators proposed for the 2002 awards were exhibited at the IBBY stand and attracted much attention.