What-Is-Curriculum-Theory-Pinar.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overcoming the Crisis in Curriculum Theory: a Knowledge-Based Approach Michael Young Version of Record First Published: 05 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [Institute of Education] On: 24 April 2013, At: 05:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Curriculum Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcus20 Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: a knowledge-based approach Michael Young Version of record first published: 05 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Michael Young (2013): Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: a knowledge- based approach, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45:2, 101-118 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.764505 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. J. CURRICULUM STUDIES, 2013 Vol. 45, No. 2, 101–118, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.764505 Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: a knowledge-based approach MICHAEL YOUNG This paper begins by identifying what it sees as the current crisis in curriculum theory. -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

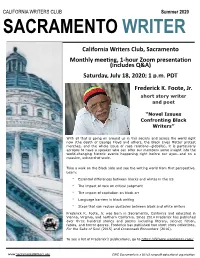

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

Andrew Sledd Revisited Terry L. Matthews, Phd / Mount Airy, North Carolina

Journal of Southern Religion, Volume 6 (December 2003) The Voice of a Prophet: Andrew Sledd Revisited Terry L. Matthews, PhD / Mount Airy, North Carolina In 1902, Andrew Sledd, a professor of Latin at Emory College published “a strong denunciation of lynching in the Atlantic Monthly.” The furor that followed the article’s appearance led the president of Emory, James Dickey, “to ask for Sledd’s resignation.” For the next 100 years, Emory University sought to gloss over or ignore this stain on its institutional soul.1 Not until April 2002, at a special symposium held to commemorate the controversy, did the University act to “right a wrong committed a century ago by revisiting the ‘Sledd affair’ and reflecting on its meaning for Emory today.”2 Indeed, Andrew Sledd’s life and work had meaning far “A man with the beyond the borders of the Emory campus. He was one of the key figures responsible for undermining the ruling courage of his orthodoxies of race, education and religion that held convictions, Sledd Southern culture in an iron grip for far too long. Although was prepared to pay hardly perfect, Sledd was one of those rare persons who a high price for his possessed the character and courage to labor heroically dissent as he for a new South, even though he was only able to see and greet it from afar. A self styled “Apostle of the New embarked on a life South,” Sledd spoke out forcefully against the “infidelity long struggle against of the orthodox” proclaiming a gospel of “righteousness the ‘blind adherents’ and social service” that would inspire his students at Emory College and the Candler School of Theology to of racism, anti- 3 intellectualism, and become agents of change across the region. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Nikki Giovanni

Nikki Giovanni and if ever I touched a life I hope that life knows that I know that touching was and still is and will always be the true revolution “ — “When I Die” from My House (1972) Biography Quick Facts Nikki Giovanni was born on June 7, 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee under * Born in 1943 her birth name, Yolande Cornelia Giovanni, Jr. She was raised in Cincin- nati, Ohio where she left high school as a junior in order to attend Fisk * Black” Rights University, a historically black institution. As an undergraduate, she poet, activist, became increasingly involved in politics surrounding race as well as art. and educator She involved herself with the Black Arts Movement and in 1964 led the * First published organizing of the influential civil rights organization, the Student Non- book of poetry violent Coordinating Committee (Reid 46). As she became more active was Black in the struggle surrounding race in the sixties she edited a student literary Judgment journal. During this time, Giovanni began to emerge as a revolutionary Black Rights poet. Giovanni’s poetry spans over thirty years, from her first book in 1968 to her most recent collection Blues For All the Changes (1998). In her most comprehensive work of poetry, The Selected Poems of Nikki Giovanni (1996), the reader experiences vast changes in a poet’s early contentious poetry and later, more personal poetry. This page was researched and submitted by Ryan Wahlberg and Bianca Ward on 5/23/01. 1 © 2009 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. -

Journal of Curriculum Studies Research Critical Teaching in Classrooms of Healing: Struggles and Testimonios

https://curriculumstudies.org E-ISSN: 2690-2788 Journal of Curriculum Studies Research June 2020 Volume: 2 Issue: 1 pp. 95-111 Critical teaching in classrooms of healing: Struggles and testimonios Brian C. Gibbs* * The University of North Carolina at ABSTRACT Chapel Hill, School of Education, Chapel Using testimonio methodology, this article describes the Hill, North Carolina, USA. testimonio and struggle of two Chicanx activist social studies E-mail: [email protected] teachers teaching in a large urban high school serving socio- economically poor Latinx students. Both teach critically, Article Info working to develop their students’ understanding of how their Received: April 24, 2020 ethnic and community histories contrast with larger historical Revised: May 16, 2020 narratives. Both teach the racism, misogyny, and homophobia Accepted: May 16, 2020 rampant in American history by connecting it to the present. They also engage a culturally sustaining pedagogy to give 10.46303/jcsr.02.01.6 students strength from their cultural inheritance. Each approached this differently, one developing an ethnic studies This is an Open Access article distributed course, and the second developing a circulo de hombres, and under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 embedding a youth participation action research. Each teacher International license. tackled critical teaching and healing simultaneously from (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- different perspectives yielding a variety of accompanying nc-nd/4.0) struggles. KEYWORDS How to cite Ethnic studies; critical pedagogy; social justice teaching; Gibbs, B. C. (2020). Critical teaching in restorative justice. classrooms of healing: Struggles and testimonios. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 2(1), 95-111. -

From Course Objectives, They Should Develop Their Tests Based on A

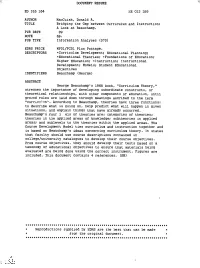

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 316 164 HE 023 289 AUTHOR MacCuish, Donald A. TITLE Bridging the Gap between Curriculum and Instruction: A Look at Beauchamp. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 6p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Curriculum Development; Educational Planning; *Educational Theories; *Foundations of Education; Higher Education; *Instruction; Instructional Development; Models; Student Educational Objectives IDENTIFIERS Beauchamp (George) ABSTRACT George Beauchamp's 1968 book, "Curriculum Theory," stresses the importance of developing subordinate constructs, or theoretical relationships, with other components of education, until ground rules are laid down through meanings ascribed to the term "curriculnm". According to Beauchamp, theories have three functions: to describe what is going on, help predict what will happen in given situations, and explain things that have already occurred. Beauchamp's four 1 els of theories are: categories of theories; theories in the applied areas of knowledge; subtheories in applied areas; and sublevels to the theories within the applied areas. The Course Development Model ties curriculum and instruction together and is based on Beauchamp's ideas concerning curriculum theory. It states that faculty should use course descriptions contained in college/university catalogues to develop their course objectives. From course objectives, they should develop their tests based on a taxonomy of educational objectives to ensure that materials being evaluated are being done using the -

John Dewey's Theory of Experience and Learning

24 Towards a Flexible Curriculum John Dewey's Theory of Experience and Learning Joop W. A. Berding Introduction In what I call the technological approach some traits from the teacher or subject-centered tradition can be recognized In the history of curriculum we see lines of divergence and in what I have named Bildung some traits from the child- into two separate schools. On the one hand, we can find a centered tradition can be discerned. view that emphasizes the school-based distribution of selected Looking at contemporary educational theory, of which knowledge. 'Education' is conceptualized as intervention, (i.e. curriculum theory is an essential part, one can see that the the transmission of a bulk of tradition-given, indisputable first school has become the dominant one, as a sort of knowledge), in which the experiences of the learner (inside 'standard-view' of curriculum. Summarized, its main features or outside the school) only count in relation to externally include: defined objectives. The success of education is primarily 1. a conglomeration of atomistic, cognitivistic, de- measured in terms of 'qualification,' that is meeting up to socialized, de-personalized and de-contextualized predetermined, 'objective' standards. We might call this a 'fillings', mostly defined as 'subject matter' or technological, product-oriented outlook on education and studies; curriculum. Its keywords are transmission and control. 2. a catalogue or canon, that is an autonomous, almost On the other hand there is a tradition in which the pupil/ unpersonal entity, isolated from and a priori to the learner is in the center of the educational process. -

Understanding the Use of Learner-Centered Teaching Strategies by Secondary Educators

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Understanding the Use of Learner-Centered Teaching Strategies by Secondary Educators Carmen M. Cain Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Education This is to certify that the doctoral study by Carmen M. Cain has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Heather Caldwell, Committee Chairperson, Education Faculty Dr. Michelle McCraney, Committee Member, Education Faculty Dr. Barbara Schirmer, University Reviewer, Education Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract Understanding the Use of Learner-Centered Teaching Strategies by Secondary Educators by Carmen M. Cain MA, University of Mary, 2016 BS, University of Mary, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Walden University June 2020 Abstract Use of learner-centered teaching strategies (LCTS) in the classroom practices improves academic achievement. Secondary educators do not consistently demonstrate the use of these strategies. The purpose of this study was to investigate how secondary educators were using LCTS in their instruction and what support they perceived to need to use such strategies. -

Critical Race Theory in Education: Analyzing African American Students’ Experience with Epistemological Racism and Eurocentric Curriculum

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2019 Critical race theory in education: analyzing African American students’ experience with epistemological racism and eurocentric curriculum Sana Bell DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Sana, "Critical race theory in education: analyzing African American students’ experience with epistemological racism and eurocentric curriculum" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 272. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRITICAL RACE THEORY: EPISTEMOLOGICAL RACISM Critical Race Theory in Education: Analyzing African American Students’ Experience with Epistemological Racism and Eurocentric Curriculum June, 2019 BY Sana Bell Interdisciplinary Self-Designed Program College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 1 CRITICAL RACE THEORY: EPISTEMOLOGICAL RACISM Contents Abstract 3 Section 1 Introduction: The Intersection of White Supremacy Ideology and Curriculum— Epistemological Racism 4 Purpose 4 Conceptual, -

Issues and Prospects of Effetive Implementation of New Secondary School Curriculum in Nigeria

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.34, 2015 Issues and Prospects of Effetive Implementation of New Secondary School Curriculum in Nigeria Ali A. Ahmadi Mumuye Departmet, C.O.E., P.M.B 1021, Zing, Taraba State Ajibola A. Lukman Educational Foundations, Department, C.O.E., P.M.B 1021, Zing, Taraba State Abstract This paper digs into the issues surrounding effective implementation of new secondary school curriculum in Nigeria. This is based on the feeling that 21 st century education is characterized with a dramatic technological revolution. The paper therefore portrays education in the 21 st century as a total departure from the factory-model education of the past. It is abandonment of teacher centered, paper and pencil schooling. It means a new way of understanding the concept of knowledge, a new definition of the educated person. The paper argues that society institutionalized education as a tool to reform society and creates change for the betterment. Hence, authentic education addresses the whole child, the whole person and does not limit our professional development and curriculum design to workplace readiness. To this end, there is every need to review the status quo of secondary school curriculum in Nigeria in order to consolidate further the new basic education programme and to ensure the actualization of the Federal government national developmental programme especially in the area of human capital development. Finally, the paper recommends massive advocacy and sensitization of teachers, students, parents and school administrators and supervisors who are the end-users of the new curriculum for its effective implementation.