Where the West Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 20, 2017 Movie Year STAR 351 P Acu Lan E, Bish Op a B Erd

Movie Year STAR 351 Pacu Lane, Bishop Aberdeen Aberdeen Restaurant, Olancha Airflite Diner, Alabama Hills Ranch Anchor Alpenhof Lodge, Mammoth Lakes Benton Crossing Big Pine Bishop Bishop Reservation Paiute Buttermilk Country Carson & Colorado Railroad Gordo Cerro Chalk Bluffs Inyo Convict Lake Coso Junction Cottonwood Canyon Lake Crowley Crystal Crag Darwin Deep Springs Big Pine College, Devil's Postpile Diaz Lake, Lone Pine Eastern Sierra Fish Springs High Sierras High Sierra Mountains Highway 136 Keeler Highway 395 & Gill Station Rd Hoppy Cabin Horseshoe Meadows Rd Hot Creek Independence Inyo County Inyo National Forest June Lake June Mountain Keeler Station Keeler Kennedy Meadows Lake Crowley Lake Mary 2012 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2013 DOCUMENTARY 2013 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2014 DOCUMENTARY 2014 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2015 DOCUMENTARY 26 Men: Incident at Yuma 1957 Tristram Coffin x 3 Bad Men 1926 George O'Brien x 3 Godfathers 1948 John Wayne x x 5 Races, 5 Continents (SHORT) 2011 Kilian Jornet Abandoned: California Water Supply 2016 Rick McCrank x x Above Suspicion 1943 Joan Crawford x Across the Plains 1939 Jack Randall x Adventures in Wild California 2000 Susan Campbell x Adventures of Captain Marvel 1941 Tom Tyler x Adventures of Champion, The 1955-1956 Champion (the horse) Adventures of Champion, The: Andrew and the Deadly Double1956 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Champion, The: Crossroad Trail 1955 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Hajji Baba, The 1954 John Derek x Adventures of Marco Polo, The 1938 Gary Cooper x Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok 1951-1958 Guy Madison Affairs with Bears (SHORT) 2002 Steve Searles Air Mail 1932 Pat O'Brien x Alias Smith and Jones 1971-1973 Ben Murphy x Alien Planet (TV Movie) 2005 Wayne D. -

Under Western Stars by Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss

Under Western Stars By Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss King of the Cowboys Roy Rogers made his starring mo- tion picture debut in Republic Studio’s engaging western mu- sical “Under Western Stars.” Released in 1938, the charm- ing, affable Rogers portrayed the most colorful Congressman Congressional candidate Roy Rogers gets tossed into a water trough by his ever to walk up the steps of the horse to the amusement of locals gathered to hear him speak at a political rally. nation’s capital. Rogers’ character, Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. a fearless, two-gun cowboy and ranger from the western town of Sageville, is elected culties with Herbert Yates, head of Republic Studios, to office to try to win legislation favorable to dust bowl paved the way for Rogers to ride into the leading role residents. in “Under Western Stars.” Yates felt he alone was responsible for creating Autry’s success in films and Rogers represents a group of ranchers whose land wanted a portion of the revenue he made from the has dried up when a water company controlling the image he helped create. Yates demanded a percent- only dam decides to keep the coveted liquid from the age of any commercial, product endorsement, mer- hard working cattlemen. Spurred on by his secretary chandising, and personal appearance Autry made. and publicity manager, Frog Millhouse, played by Autry did not believe Yates was entitled to the money Smiley Burnette, Rogers campaigns for office. The he earned outside of the movies made for Republic portly Burnette provides much of the film’s comic re- Studios. -

International Geology Review Unroofing History of Alabama And

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 2 March 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918588849] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Geology Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t902953900 Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology Guleed A. H. Ali a; Peter W. Reiners a; Mihai N. Ducea a a Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA To cite this Article Ali, Guleed A. H., Reiners, Peter W. and Ducea, Mihai N.(2009) 'Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology', International Geology Review, 51: 9, 1034 — 1050 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00206810902965270 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00206810902965270 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

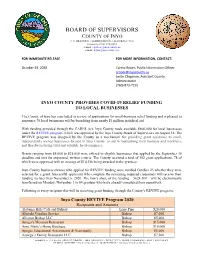

Board of Supervisors

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY OF INYO P. O. DRAWER N INDEPENDENCE, CALIFORNIA 93526 TELEPHONE (760) 878-0373 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: October 29, 2020 Carma Roper, Public Information Officer [email protected] Leslie Chapman, Assistant County Administrator (760) 873-7191 INYO COUNTY PROVIDES COVID-19 RELIEF FUNDING TO LOCAL BUSINESSES The County of Inyo has concluded its review of applications for small-business relief funding and is pleased to announce 78 local businesses will be benefiting from nearly $1 million in federal aid. With funding provided through the CARES Act, Inyo County made available $800,000 for local businesses under the REVIVE program, which was approved by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors on August 18. The REVIVE program was designed by the County as a mechanism for providing grant assistance to small, independently owned businesses located in Inyo County, to aid in maintaining their business and workforce and thereby restoring vital and valuable local commerce. Grants ranging from $5,000 to $25,000 were offered to eligible businesses that applied by the September 18 deadline and met the expressed, written criteria. The County received a total of 102 grant applications, 78 of which were approved with an average of $10,256 being awarded to the grantees. Inyo County business owners who applied for REVIVE funding were notified October 23 whether they were selected for a grant. Successful applicants who complete the remaining required credentials will receive their funding no later than November 6, 2020. The lion’s share of the funding – $624,300 – will be electronically transferred on Monday, November 1 to 64 grantees who have already completed their paperwork. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Movie History in Lone Pine, CA

Earl’s Diary - Saturday - February 1, 2014 Dear Loyal Readers from near and far; !Boy, was it cold last night! When I looked out the window this morning, the sun was shining and the wind still blowing. As I looked to the west, I found the reason for the cold. The wind was blowing right off the mountains covered with snow! The furnace in The Peanut felt mighty good! !Today was another sightseeing day. My travels took me to two sites in and around Lone Pine. The two sites are interconnected by subject matter. You are once again invited to join me as I travel in Lone Pine, California. !My first stop was at the Movie History Museum where I spent a couple hours enjoying the history of western movies - especially those filmed here in Lone Pine. I hurried through the place taking pictures. There were so many things to see that I went back after the photo taking to just enjoy looking and reading all the memorabilia. This was right up my alley. I spent my childhood watching cowboys and Indians, in old films showing on afternoon TV and in original TV shows from the early 50's on. My other interest is silent movies. This museum even covers that subject. ! This interesting place has an impressively large collection of movie props from all ages of film. They've got banners and posters from the 20's, sequined cowboy jumpers and instruments used by the singing cowboys of the 30's and 40's, even the guns and costumes worn by John Wayne, Clint Eastwood and several other iconic cowboy actors. -

Alabama Hills Management Plan Comments

Steve Nelson, Field Manager Sherri Lisius, Assistant Field Manager Bureau of Land Management 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted via email: [email protected] RE: DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA Bishop BLM Field Office and Alabama Hills Planning Team, Thank you for the opportunity to review and submit comments on the DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA for the Alabama Hills Draft Management Plan, published July 8th 2020. Please accept these comments on behalf of Friends of the Inyo and our 1,000+ members across the state of California and country. About Friends of the Inyo & Project Background Friends of the Inyo is a conservation non-profit 501(c)(3) based in Bishop, California. We promote the conservation of public lands ranging from the eastern slopes of Yosemite to the sands of Death Valley National Park. Founded in 1986, Friends of the Inyo has over 1,000 members and executes a variety of conservation programs ranging from interpretive hikes, trail restoration, exploratory outings, and public lands policy engagement. Over our 30-year history, FOI has become an active partner with federal land management agencies in the Eastern Sierra and California Desert, including extensive work with the Bishop BLM. Friends of the Inyo was an integral partner in gaining the passage of S.47, or the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, that designated the Alabama Hills as a National Scenic Area. Our board and staff have served this area for many years and have seen it change over time. With this designation comes the opportunity to address these changes and promote the conservation of the Alabama Hills. -

Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514

December 23, 2019 BLM Bishop Field Office Attn: Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted Via Email to [email protected]: RE: Access Fund Comments on Alabama Hills Management Plan Scoping Process Dear BLM Bishop Field Office Planning Staff, The Access Fund and Outdoor Alliance California (OACA) appreciate this opportunity to provide preliminary comments on the BLM’s initial scoping process for the Alabama Hills National Scenic Area (NSA) and National Recreation Area (NRA) Management Plan. The Alabama Hills provide a unique and valuable climbing and recreational experience within day trip distance of several major population centers. The distinct history, rich cultural resources, dramatic landscape, and climbing opportunities offered by the Alabama Hills have attracted increasing numbers of visitors, something which the new National Scenic Area designation1 will compound, leading to a need for proactive management strategies to mitigate growing impacts from recreation. We look forward to collaborating with the BLM on management strategies that protect both the integrity of the land and continued climbing opportunities. The Access Fund The Access Fund is a national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conserves the climbing environment. A 501c(3) nonprofit and accredited land trust representing millions of climbers nationwide in all forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is a US climbing advocacy organization with over 20,000 members and over 123 local affiliates. Access Fund provides climbing management expertise, stewardship, project specific funding, and educational outreach. California is one of Access Fund’s largest member states and many of our members climb regularly at the Alabama Hills. -

Geologic Map of the Lone Pine 15' Quadrangle, Inyo County, California

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS SERIES U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP I–2617 118°15' 118°10' 118°5' 118°00' ° 36°45' 36 45' CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Alabama Hills Early Cretaceous age. In northern Alabama Hills, dikes and irregular hy- SW1/4NE1/4 sec. 19, T. 15 S., R. 37 E., about 500 m east of the boundary with the Lone tures that define the fault zone experienced movement or were initiated at the time of the Kah Alabama Hills Granite (Late Cretaceous)—Hypidiomorphic seriate to pabyssal intrusions constitute more than 50 percent, and locally as much Pine 15' quadrangle. Modal analyses of 15 samples determined from stained-slab and 1872 earthquake. SURFICIAL DEPOSITS d faintly porphyritic, medium-grained biotite monzogranite that locally as 90 percent, of the total rock volume over a large area (indicated by thin-section point counts indicate that the unit is composed of monzogranite (fig. 4). Ad- Most traces of the Owens Valley Fault Zone in the quadrangle cut inactive alluvium contains equant, pale-pink phenocrysts of potassium feldspar as large as pattern). Some of these dikes may be genetically associated with the ditional description and interpretation of this unusual pluton are provided by Griffis (Qai) and older lake deposits (Qlo). Some scarps, however, cut active alluvial deposits Qa 1 cm. Outcrop color very pale orange to pinkish gray. Stipple indicates lower part of the volcanic complex of the Alabama Hills (Javl) (1986, 1987). (Qa) that fringe the Alabama Hills north of Lone Pine, and the most southeasterly trace of Qly Qs local fine-grained, hypabyssal(?) facies. -

Lone Pine / Mt. Whitney 23-24 Snowboarders

Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide 2011-2012 >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts xtending 165 miles along the White Mountain and Owens River Mam moth Mountain Ski California/Nevada border Headwaters wildernesses. Devils Area becomes a sum mer “Inyo” is a Paiute Ebetween Los Angeles and Postpile Na tion al Mon u ment, mecca for mountain bike Reno, the Inyo National Forest, ad min is tered by the National Park en thu si asts as they ride Indian word meaning established May 25, 1907, in cludes Ser vice, is also located within the the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze 1,900,543 acres of pris tine lakes, Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds Trail from the top of the “Dwelling Place of fragile mead ows, wind ing streams, Mead ow area west of Mam moth 11,053foot high rugged Sierra Ne va da peaks and Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home Mam moth Moun tain or the Great Spirit.” arid Great Basin moun tains. El e va to the tallest peak in the low er 48 one of the many other trails tions range from 3,900 to 14,497 states, Mt. Whitney (14,497 feet) that transect the front feet, pro vid ing diverse habitats and is adjacent to the lowest point coun try of the forest. that sup port vegetation patterns in North America at Badwater in Thirtysix trailheads provideJ ranging from semiarid deserts to Death Val ley Na tion al Park (282 ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail high al pine fellfields. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew. -

Manzanar National Historic Site Geologic Resource Evaluation

MANZANAR NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE GEOLOGIC RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ISSUES SCOPING SUMMARY Sid Covington Geologic Resources Division October 26, 2004 Executive Summary Geologic Resource Evaluation scoping meetings for three parks in the Mojave Network were held April 28 - May 1, 2003, in St George, UT, Barstow, CA, and Twentynine Palms, CA, respectively. Unfortu- nately, due to time and travel constraints, scoping was not done at Manzanar National Historic Site (MANZ). The following report identifies the major geologic issues and describes the geology of MANZ and the surrounding the area. The major geologic issues affecting the park are: 1. Flooding and erosion due to runoff from the Sierra Nevada mountains to the west. 2. Recurring seismic activity 3. The potential for volcanic activity from Long Valley Caldera 4. Proposed gravel pit upslope from MANZ Introduction The National Park Service held Geologic Resource Evaluation scoping meetings for three parks in the Mojave Network: Parashant National Monument, Mojave National Preserve, and Joshua Tree National Park. These meeting were held April 28 - May 1, 2003, in St George, UT, Barstow, CA and Twentynine Palms, CA respectively. The purpose of these meeting was to discuss the status of geologic mapping, the associated bibliography, and the geologic issues in the respective park units. The products to be derived from the scoping meeting are: (1) Digitized geologic maps covering the park units; (2) An updated and verified bibliography; (3) Scoping summary (this report); and (4) A Geologic Resources Evaluation Report which brings together all of these products. Although there was no onsite scoping for MANZ, these products will be produced for the historic site.