How a Picture Comes out IC 405 and IC 410 Nebulas in Auriga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Flaming Star the Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405) in the Constellation Auriga Is a Surprisingly Colorful and Dramatic Emission/Reflection Nebula

WESTCHESTER AMATEUR ASTRONOMERS January 2016 Image Copyright: Mauri Rosenthal Flaming Star The Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405) in the constellation Auriga is a surprisingly colorful and dramatic emission/reflection nebula. In This Issue . The most prominent star in the image is the variable blue dwarf AE pg. 2 Events For January Aurigae, burning with sufficient intensity to knock electrons off pg. 3 Almanac the hydrogen molecules found in a cloud 5 light years across, pg. 4 Vivian Towers which in turn emit red light. The bluish gray area is not from ion- pg. 5 The Radio Sky ized Oxygen (as found in the Veil Nebula); rather it is mostly a pg. 11 Kepler cloud of carbon dust, which reflects the blue light from the nearby pg. 12 President’s Report star. The result is an emission/reflection nebula 1500 light years distant and accessible from the suburbs with a small telescope. Mauri Rosenthal imaged this from his backyard in Scarsdale with a guided Questar 3.5” telescope over two nights in November using CLS (broadband) and H-alpha (narrowband) filters. Total exposure time was 9.5 hours. SERVING THE ASTRONOMY COMMUNITY SINCE 1986 1 WESTCHESTER AMATEUR ASTRONOMERS January 2016 WAA January Lecture Club Dates 2016 “Light Pollution” Friday January 8th, 7:30pm 2016 Lecture Dates Leinhard Lecture Hall, January 8 June 3 February 5 Sept. 16 Pace University, Pleasantville, NY March 4 October 7 Charles Fulco will speak on light pollution, the Inter- April 1 November 4 national Dark-Sky Association and preserving our May 6 December 2 night sky. -

August 2012 of You Know I Went to the Astronomical League Conference (Alcon) in Chicago at the Beginning of July with My Grandmother

BACKBACK BAYBAY observerobserver The Official Newsletter of the Back Bay Amateur Astronomers P.O. Box 9877, Virginia Beach, VA 23450-9877 Looking Up! Hello again! This month I actually have a story EPHEMERALS to tell, instead of just random ramblings. As most august 2012 of you know I went to the Astronomical League Conference (ALCon) in Chicago at the beginning of July with my grandmother. It was great. Not quite 08/24, 7:00 pm as good as last year, seeing as I had to pay for it Night Hike and they didn’t give me a check and a plaque this Northwest River Park year (last year I won the Horkheimer Youth award, which paid for my trip), but it was still a lot of fun, and very educational. I met a lot of cool 08/24, 8:00 pm people and definitely learned something. The Garden Stars whole trip was a big story, but a few events stand Norfolk Botanical Gardens out the most in my memory, and they’re all connected to some extent. 08/28, 7:00 pm Boardwalk Astronomy It all started on the day we got there. ALCon is Near 24th St Stage an annual four day conference usually in the VA Beach Oceanfront beginning of July. This year, the day we got there was July fourth. After checking in, taking a nap and 09/06, 7:30 pm dining, we decided to participate in the observing BBAA Monthly Meeting event outside the hotel. It was in a parking lot with lights, and fireworks, but there was a large moon TCC Campus and Saturn was up, so we went for it. -

Possible Groupings of Irregular (Orion) Variables

POSSIBLE GROUPINGS OF IRREGULAR (ORION) VARIABLES M. V. DOLIDZE Abastumani Observatory, Abastumani, Georgia, U.S.S.R. Abstract. New groupings of Ha-emission stars connected with young clusters, asso ciations and nebulae are considered to be possible regions of clusterings of irregular (Orion-type) variables. They are listed in Table I and an example, No. 19, is shown in Figure 1. Finding charts of individual stars and more detailed data will be given in two forth coming papers in the Bulletins of the Abastumani Astrophysical Observatory. TABLE I Regions of possible clustering of irregular (Orion) variables (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) No. Regions Ha ai9oo &900 Central Type em. O or T Ass 1 NGC 281 +Kh 215 1 00h45™2 55°51' a: 2 IC 1805; 1795 + Kh 237 11 02 25.2 61 01 43, Cas OB 6 b: 2 O CI 357, NGC 1027 1 02 35.0 61 07 43, Cas OB 6 3 S126, OC1 435 + Kh281 2 05 08.1 32 37 8, IC 405 a:; c 4 MWC 789 + Kh 297 1 05 56.4 16 49 a 4 S34, McD 43 + Kh 297 1 06 03.3 15 48 5 IC 4601+Kh 569 1 16 15.5 -20 00 v Sco a: 6 S 190 4 18 13.0 -12 00 9, Ser OB 2 7 OC1 38, IC 4725 + D 1 18 25.0 -19 19 c 8 NGC 6820, 6823 3 19 39.0 23 06 13, Vul OB 1 b: 9 OC1 An (Do 1974)+ D 4 19 40.7 24 20 14, Vul OB 4 b:;c: 10 S 67, B 346 6 20 21.5 43 00 39, T2 Cyg a: 11 Kh 100 3 20 38.0 33 20 a: 12 S86 + D 1 21 00.3 59 04 13 S88 + Kh 127 1 21 15.2 42 57 14 near (NGC 7086 + Kh 141) 2 21 25.0 49 50 15 Kh 160 5 21 47.1 55 56 27, Cep OB 2 a: 16 Kh 172 5 22 01.6 58 48 a: 16 S94, Mi 16 + D 9 22 20.2 58 17 17 S95, McD 30+ D 2 22 21.4 63 04 16 S96, W94 + D 5 22 33.2 58 00 18 O CI 248, An (King 10) + D 4 22 51.0 58 36 c; d 19 Sh 155+ D 10 22 52.3 62 00 30, Cep OB 3 b:; d 20 MWC 1080 + D 4 23 11.7 60 20 a 21 Kh 198 1 23 50.8 58 03 a: Sherwood and Plaut (eds.), Variable Stars and Stellar Evolution, 109-111. -

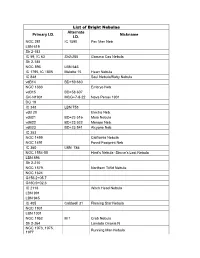

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

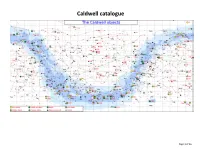

Caldwell Catalogue - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Caldwell catalogue - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Caldwell catalogue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents The Caldwell Catalogue is an astronomical catalog of 109 bright star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies for observation by amateur astronomers. The list was compiled Featured content by Sir Patrick Caldwell-Moore, better known as Patrick Moore, as a complement to the Messier Catalogue. Current events The Messier Catalogue is used frequently by amateur astronomers as a list of interesting deep-sky objects for observations, but Moore noted that the list did not include Random article many of the sky's brightest deep-sky objects, including the Hyades, the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884), and NGC 253. Moreover, Moore observed that the Donate to Wikipedia Messier Catalogue, which was compiled based on observations in the Northern Hemisphere, excluded bright deep-sky objects visible in the Southern Hemisphere such [1][2] Interaction as Omega Centauri, Centaurus A, the Jewel Box, and 47 Tucanae. He quickly compiled a list of 109 objects (to match the number of objects in the Messier [3] Help Catalogue) and published it in Sky & Telescope in December 1995. About Wikipedia Since its publication, the catalogue has grown in popularity and usage within the amateur astronomical community. Small compilation errors in the original 1995 version Community portal of the list have since been corrected. Unusually, Moore used one of his surnames to name the list, and the catalogue adopts "C" numbers to rename objects with more Recent changes common designations.[4] Contact Wikipedia As stated above, the list was compiled from objects already identified by professional astronomers and commonly observed by amateur astronomers. -

Caldwell Catalogue

CALDWELL CATALOGUE 1 Caldwell Catalog Distance Viewing C NGC Type Mag RA Dec Constellation Common Name (ly) Season 1 188 Open Cluster 8.1 4800 00:44.4 +85:20 Cepheus autumn 240 Planetary Nebula 11.6 3500 00:13.0 +72:32 Cepheus autumn Bow Tie Nebula 3 4236 Spiral Galaxy 9.7 7 million 12:16.7 +69:28 Draco spring 4 7023 Bright Nebula 6.8 1400 21:01.8 +68:12 Cepheus autumn Iris Nebula 5 IC 342 Spiral Galaxy 9.2 13 million 03:46.8 +68:06 Camalopardalis winter 6 6543 Planetary Nebula 8.8 3000 17:58.6 +66:38 Draco summer Cat's Eye Nebula 7 2403 Spiral Galaxy 8.9 14 million 07:36.9 +65:36 Camalopardalis winter 8 559 Open Cluster 9.5 3700 01:29.5 +63:18 Cassiopeia autumn 9 Sh2-155 Bright Nebula 7.7 2800 22:56.8 +62:37 Cepheus autumn Cave Nebula 10 663 Open Cluster 7.1 7200 01:46.0 +61:15 Cassiopeia autumn 11 7635 Bright Nebula 7 7100 23:20.7 +61:12 Cassiopeia autumn Bubble nebula 12 6946 Spiral Galaxy 9.7 18 million 20:34.8 +60:09 Cepheus summer 13 457 Open Cluster 6.4 - 01:19.1 +58:20 Cassiopeia autumn Owl or E.T. Cluster 14 869/884 Open Cluster 4.3 7300 02:20.0 +57:08 Perseus autumn Double Cluster, h & chi Persei 15 6826 Planetary Nebula 9.8 2200 19:44.8 +50:31 Cygnus summer Blinking Planetary 16 7243 Open Cluster 6.4 2500 22:15.3 +49:53 Lacerta autumn 17 147 Elliptical Galaxy 9.3 2300000 00:33.2 +48:30 Cassiopeia autumn 18 185 Elliptical Galaxy 9.2 2300000 00:39.0 +48:20 Cassiopeia autumn 19 IC 5146 Bright Nebula 10 3300 21:53.5 +47:16 Cygnus autumn Cocoon Nebula 20 7000 Bright Nebula 6 1800 20:58.8 +44:20 Cygnus summer North America Nebula 21 4449 Irregular Galaxy 9.4 10 million 12:28.2 +44:06 Canceres Venatici spring 22 7662 Planetary Nebula 9.2 3200 23:25.9 +42:33 Andromeda autumn Blue Snowball 23 891 Spiral Galaxy 9.9 31 million 02:22.6 +42:21 Andromeda autumn 24 1275 Irregular Galaxy 11.6 230 mil. -

The Caldwell Catalog

DEEP-SKY OBSERVING This inventory of 109 deep-sky treasures rivals Charles Messier’s list in diversity and delight. /// TEXT BY MICHAEL E. BAKICH /// IMAGES BY ADAM BLOCK The Caldwell Catalog Regarding object selection, relative to M11. M20. M31. Every amateur Messier’s list, Moore slightly reduced the astronomer recognizes these designations because this trio of numbers in certain categories while deep-sky objects is found on the list of 18th-century comet increasing others. So the number of star clusters (both open and globular) and hunter Charles Messier. M11 is the Wild Duck Cluster in galaxies was reduced slightly, but the num- Scutum; M20 is the Trifid Nebula in Sagittarius; and M31 is ber of nebulae was increased. Only four the Andromeda Galaxy. But what if the letter C replaces the planetary nebulae made Messier’s list, but Moore placed 13 in the Caldwell Catalog. M in front of those numbers? Would you Likewise, Moore increased the number of recognize C11, C20, and C31? This trio of bright nebulae from five to 12. deep-sky objects is also well known, but C48 Moore also distributed his objects more perhaps not by these designations. The C (NGC 2775) widely across the sky. Sagittarius and stands for Caldwell, or more specifically, Virgo, which have 15 and 11 Messier for Caldwell-Moore, the full surname of objects, respectively, have only one well-known British astronomy popularizer Caldwell object each. Perhaps Moore Sir Patrick Moore. When it came time to thought most of the great objects in those place an identifier by each of the num- constellations were taken. -

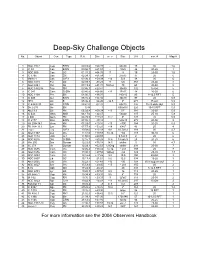

Terry Adrians' Deep-Sky Challenge Objects Chart

Deep-Sky Challenge Objects No. Object Con Type R.A. Dec m_v Size U # min. A Map # 1 NGC 7822 Cep E/RN 00:03.6 +68:37 - 60x30 15 30 1,6 2 IC 59 Cas E/RN 00:56.7 +61:04 - 10x5 36 20-25 1 3 NGC 609 Cas OC 01:37.2 +64:33 11 3 16 25-30 1,6 4 IC 1795 Cas EN 02:24.7 +61:54 - 27x13 17 20 6 5 Maffei 1 Cas G-E3 02:36.3 +59:39 ~14 5x3 38 30 6 6 NGC 1049 For GC 02:39.7 -34:29 11 0.6 354 25-30 8 7 Abell 426 r Per Gs 03:19.8 +41:31 16-Dec 30 63 20-40 5 8 NGC 1432/35 Tau RN 03:46.1 +23:47 30x30 132 15-Oct 5 9 IC 342 Cam G-SBc 03:46.8 +68:06 ~12 17x17 18 20-30 6 10 NGC 1499 Per EN 04:00.7 +36:37 145x40 95 8-12.5 RFT 5 11 IC 405 Aur E/RN 05:16.2 +34:16 30x19 97 20 5,9 12 HH1 Ori E 05:36.3 -06:45 ~14.5 8" 271 15-Oct 5,9 13 IC 434/B 33 Ori E/DN 05:41.0 -02:28 60x10 226 15-20 dark sky! 5,9 14 Sh 2-276 Ori EN 5:48 1 600x30! 226 10-15 RFT 5,9 15 Abell 12 Ori PN 06:02.4 +09:39 ~13 37" 181 25-30 5,9 16 IC 443 Gem SNR 06:17.0 +22:47 50x40 137 25-30 5,9 17 J 900 Gem PN 06:25.9 +17:47 12.2 8" 137 20 5,9 18 IC 2177 Mon E/RN 07:05.1 -10:42 120x40 273 20-30 9 19 PK 205+14.1 Gem PN 07:29.0 +13:15 ~13 ~700 184 20-25 5,9 20 PK 164+31.1 Lyn PN 07:57.8 +53:25 ~14 6'40" 43 25 4 21 Leo I Leo G-E3 10:08.0 +12:18 9.8 10.7x8.3 189 30 4,7 22 Abell 1367 Leo G's 11:44.0 +19:57 13-16 ~60 147 30-40 6 23 NGC 3172 UMi G-? 11:50.0 +89:07 0.7x0.7 2 25 6 24 NGC 4236 Dra G-SBb 12:16.7 +69:28 13.6 18.6x6.9 25 20-25 6 25 Mrk 205 Dra Quasar 12:22.0 +75:18 14.5 stellar 9 30 4,7 26 3C 273 Vir Quasar 12:29.1 +02:03 12-Deg stellar 238 25-30 7 27 NGC 4676 Com G's 12:46.2 +30:44 14.1p ~ 2x1 108 -

Imaging Van Den Bergh Objects

Deep-sky observing Explore the sky’s spooky reflection nebulae vdB 14 You’ll need a big scope and a dark sky to explore the van den Bergh catalog’s challenging objects. text and images by Thomas V. Davis vdB 15 eflection nebulae are the unsung sapphires of the sky. These vast R glowing regions represent clouds of dust and cold hydrogen scattered throughout the Milky Way. Reflection nebulae mainly glow with subtle blue light because of scattering — the prin- ciple that gives us our blue daytime sky. Unlike the better-known red emission nebulae, stars associated with reflection nebulae are not near enough or hot enough to cause the nebula’s gas to ion- ize. Ionization is what gives hydrogen that characteristic red color. The star in a reflection nebula merely illuminates sur- rounding dust and gas. Many catalogs containing bright emis- sion nebulae and fascinating planetary nebulae exist. Conversely, there’s only one major catalog of reflection nebulae. The Iris Nebula (NGC 7023) also carries the designation van den Bergh (vdB) 139. This beauti- ful, flower-like cloud of gas and dust sits in Cepheus. The author combined a total of 6 hours and 6 minutes of exposures to record the faint detail in this image. Reflections of starlight Canadian astronomer Sidney van den vdB 14 and vdB 15 in Camelopardalis are Bergh published a list of reflection nebu- so faint they essentially lie outside the lae in The Astronomical Journal in 1966. realm of visual observers. This LRGB image combines 330 minutes of unfiltered (L) His intent was to catalog “all BD and CD exposures, 70 minutes through red (R) and stars north of declination –33° which are blue (B) filters, and 60 minutes through a surrounded by reflection nebulosity …” green (G) filter. -

Charles Messier (1730-1817) Was an Observational Astronomer Working

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was an observational Catalogue (NGC) which was being compiled at the same astronomer working from Paris in the eighteenth century. time as Messier's observations but using much larger tele He discovered between 15 and 21 comets and observed scopes, probably explains its modern popularity. It is a many more. During his observations he encountered neb challenging but achievable task for most amateur astron ulous objects that were not comets. Some of these objects omers to observe all the Messier objects. At «star parties" were his own discoveries, while others had been known and within astronomy clubs, going for the maximum before. In 1774 he published a list of 45 of these nebulous number of Messier objects observed is a popular competi objects. His purpose in publishing the list was so that tion. Indeed at some times of the year it is just about poss other comet-hunters should not confuse the nebulae with ible to observe most of them in a single night. comets. Over the following decades he published supple Messier observed from Paris and therefore the most ments which increased the number of objects in his cata southerly object in his list is M7 in Scorpius with a decli logue to 103 though objects M101 and M102 were in fact nation of -35°. He also missed several objects from his list the same. Later other astronomers added a replacement such as h and X Per and the Hyades which most observers for M102 and objects 104 to 110. It is now thought proba would feel should have been included. -

Number of Objects by Type in the Caldwell Catalogue

Caldwell catalogue Page 1 of 16 Number of objects by type in the Caldwell catalogue Dark nebulae 1 Nebulae 9 Planetary Nebulae 13 Galaxy 35 Open Clusters 25 Supernova remnant 2 Globular clusters 18 Open Clusters and Nebulae 6 Total 109 Caldwell objects Key Star cluster Nebula Galaxy Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C22 NGC 7662 Blue Snowball Planetary Nebula 3.2 Andromeda 9 C23 NGC 891 Galaxy 31,000 Andromeda 10 C28 NGC 752 Open Cluster 1.2 Andromeda 5.7 C107 NGC 6101 Globular Cluster 49.9 Apus 9.3 Page 2 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C55 NGC 7009 Saturn Nebula Planetary Nebula 1.4 Aquarius 8 C63 NGC 7293 Helix Nebula Planetary Nebula 0.522 Aquarius 7.3 C81 NGC 6352 Globular Cluster 18.6 Ara 8.2 C82 NGC 6193 Open Cluster 4.3 Ara 5.2 C86 NGC 6397 Globular Cluster 7.5 Ara 5.7 Flaming Star C31 IC 405 Nebula 1.6 Auriga - Nebula C45 NGC 5248 Galaxy 74,000 Boötes 10.2 Page 3 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation number LY*103 magnitude C5 IC 342 Galaxy 13,000 Camelopardalis 9 C7 NGC 2403 Galaxy 14,000 Camelopardalis 8.4 C48 NGC 2775 Galaxy 55,000 Cancer 10.3 C21 NGC 4449 Galaxy 10,000 Canes Venatici 9.4 C26 NGC 4244 Galaxy 10,000 Canes Venatici 10.2 C29 NGC 5005 Galaxy 69,000 Canes Venatici 9.8 C32 NGC 4631 Whale Galaxy Galaxy 22,000 Canes Venatici 9.3 Page 4 of 16 Caldwell Distance Apparent NGC number Common name Image Object type Constellation