Star Formation and Molecular Clouds Towards the Galactic Anti-Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plasma Physics and Pulsars

Plasma Physics and Pulsars On the evolution of compact o bjects and plasma physics in weak and strong gravitational and electromagnetic fields by Anouk Ehreiser supervised by Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia as part of an internship at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy, Bonn March 2010 2 This composition was written as part of two internships at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in April 2009 at the Radiotelescope in Effelsberg and in February/March 2010 at the Institute in Bonn. I am very grateful for the support, expertise and patience of Axel Jessner, Maria Massi and Li Kejia, who supervised my internship and introduced me to the basic concepts and the current research in the field. Contents I. Life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure 2. Gravitational collapse and supernova 3. Star remnants II. Properties of Compact Objects 1. White Dwarfs 2. Neutron Stars 3. Black Holes 4. Hypothetical Quark Stars 5. Relativistic Effects III. Plasma Physics 1. Essentials 2. Single Particle Motion in a magnetic field 3. Interaction of plasma flows with magnetic fields – the aurora as an example IV. Pulsars 1. The Discovery of Pulsars 2. Basic Features of Pulsar Signals 3. Theoretical models for the Pulsar Magnetosphere and Emission Mechanism 4. Towards a Dynamical Model of Pulsar Electrodynamics References 3 Plasma Physics and Pulsars I. The life-cycle of stars 1. Formation and inner structure Stars are formed in molecular clouds in the interstellar medium, which consist mostly of molecular hydrogen (primordial elements made a few minutes after the beginning of the universe) and dust. -

Exploring Pulsars

High-energy astrophysics Explore the PUL SAR menagerie Astronomers are discovering many strange properties of compact stellar objects called pulsars. Here’s how they fit together. by Victoria M. Kaspi f you browse through an astronomy book published 25 years ago, you’d likely assume that astronomers understood extremely dense objects called neutron stars fairly well. The spectacular Crab Nebula’s central body has been a “poster child” for these objects for years. This specific neutron star is a pulsar that I rotates roughly 30 times per second, emitting regular appar- ent pulsations in Earth’s direction through a sort of “light- house” effect as the star rotates. While these textbook descriptions aren’t incorrect, research over roughly the past decade has shown that the picture they portray is fundamentally incomplete. Astrono- mers know that the simple scenario where neutron stars are all born “Crab-like” is not true. Experts in the field could not have imagined the variety of neutron stars they’ve recently observed. We’ve found that bizarre objects repre- sent a significant fraction of the neutron star population. With names like magnetars, anomalous X-ray pulsars, soft gamma repeaters, rotating radio transients, and compact Long the pulsar poster child, central objects, these bodies bear properties radically differ- the Crab Nebula’s central object is a fast-spinning neutron star ent from those of the Crab pulsar. Just how large a fraction that emits jets of radiation at its they represent is still hotly debated, but it’s at least 10 per- magnetic axis. Astronomers cent and maybe even the majority. -

The Desert Sky Observer

Desert Sky Observer Volume 32 Antelope Valley Astronomy Club Newsletter February 2012 Up-Coming Events February 10: Club Meeting* February 11: Moon Walk @ Prime Desert Woodlands February 13: Executive Board Meeting @ Don’s house February 18: Telescope Night and Star Party @ Devil's Punchbowl * Monthly meetings are held at the S.A.G.E. Planetarium on the Cactus School campus in Palmdale, the second Friday of each month. The meeting location is at the northeast corner of Avenue R and 20th Street East. Meetings start at 7 p.m. and are open to the public. Please note that food and drink are not allowed in the planetarium President Don Bryden Well I gave a star party and no one showed up! Not that I can blame them – it was raining and windy and cold – it even hailed! Still I dragged out the scope and got it ready to go. Briefly, between the clouds I looked at Jupiter and it was quite a treat. The Galilean moons were all tight to the planet either coming from just in front or behind. It gave a bejeweled look like a large ruby surrounded by four small diamonds. Even with the winds and clouds the sky was surprisingly steady and I went as high as 260x with ease, exposing the shadow of Europa transiting the planet. But soon more clouds came and inside we had a nice fire so I put the Artist's rendering DVD “400 Years of the Telescope” on and settled in for the night. My daughter had a few friends over after a skating party that afternoon and later when I went out for one more look they came out to see what was up. -

Expected Differences Between AGB Stars in the LMC and the SMC Due to Differences in Chemical Composition

New Views of the Magellanic Clouds fA U Symposium, Vol. 190, 1999 Y.-H. Chu, N.B. Suntzef], J.E. Hesser, and D.A. Bohlender, eds. Expected Differences between AGB Stars in the LMC and the SMC Due to Differences in Chemical Composition Ju. Frantsman Astronomical Institute, Latvian University, Raina Blvd. 19, Riga, LV-1586, LATVIA Abstract. Certain aspects of the AGB population, such as the relative number of M and N stars, the mass loss rates, and the initial masses of carbon- oxygen cores, depend on the initial heavy element abundance Z. I have calculated synthetic populations of AGB stars for different initial Z values taking into consideration the evolution of single and close binary stars. I present the results of population syntheses of AGB stars in clusters as a function of different initial chemical compositions. The relation for the tip luminosity of AGB stars versus cluster age as a function of Z is presented and is used to determine the ages for a number of clusters in the LMC and the SMC, including clusters with no previous age determinations. Population simulations show that for low heavy element abundance (Z = 0.001) few M stars are formed with respect to the number of carbon stars. However, the total number of all AGB stars in clusters is not affected by the initial chemical composition. As a result of the evolution of close binary components after the mass exchange, an increase in the range of limiting values of the thermal pulsing AGB star luminosities is expected. The difference between the maximum luminosity on the AGB of single star and the luminosity of a star after a mass exchange event in a close binary system may be as great as 1 magnitude for very young clusters. -

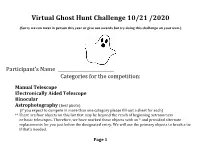

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure

Impact of Supernovae on Molecular Cloud Evolution Dynamics and Structure Bastian K¨ortgen1, Daniel Seifried1, and Robi Banerjee1 1Hamburger Sternwarte, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Introduction We perform numerical simulations of colliding streams of the WNM, including magnetic fields and self{gravity, to analyse the formation and evolution of molecular clouds subject to supernova feedback from massive stars. Simulation Setup The Supernova Subgrid Model The equations of MHD together with selfgravity and heating and cooling are evolved in time using the The supernova feedback is included into the model by means of a Sedov blast FLASH code [Fryxell et al., 2000]. We use a constant heating rate Γ and the cooling function Λ according to wave solution. We define a volume of radius R = 1 pc centered on the sink [Koyama and Inutsuka, 2000] and [V´azquez-Semadeni et al., 2007]. The table below lists the initial conditions. particle. Within this volume each grid cell is assigned a certain radial veloc- ity vc. This velocity depends on the kinetic energy input. Additionally we U Sink Particle Parameter Value Parameter Value inject thermal energy, which then gives the total amount of injected energy of E = 1051 erg with 65 % thermal and 35 % kinetic energy according to the Flow Mach number Mf 2.0 Alfv´en velocity va [km/s] 5.8 sn Sedov solution. The cell velocity is Turbulent Mach number Ms 0.5 Alfv´enic Mach number Ma 1.96 r vc = Ush Temperature [K] 5000 Plasma Beta β = Pth=PB 1.93 R Number density n cm−3 1.0 Flow Length [pc] 112 Figure 1: Schematic of the where U is the shock velocity, depending on the kinetic energy input. -

Reconsidering the Identification of M101 Hypernova Remnant

Reconsidering the Identification of M101 Hypernova Remnant Candidates S. L. Snowden1,2, K. Mukai1,3, and W. Pence4 Code 662, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 and K. D. Kuntz5 Joint Center for Astrophysics, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, 21250 ABSTRACT Using a deep Chandra AO-1 observation of the face-on spiral galaxy M101, we examine three of five previously optically-identified X-ray sources which are spatially correlated with optical supernova remnants (MF54, MF57, and MF83). The X-ray fluxes from these objects, if due to diffuse emission from the remnants, are bright enough to require a new class of objects, with the possible attribution by Wang to diffuse emission from hypernova remnants. Of the three, MF83 was considered the most likely candidate for such an object due to its size, nature, and close positional coincidence. However, we find that MF83 is clearly ruled out as a hypernova remnant by both its temporal variability and spectrum. The bright X-ray sources previously associated with MF54 and MF57 are seen by Chandra to be clearly offset from the optical positions of the supernova remnants by several arc seconds, confirming a result suggested by the previous work. MF54 does have a faint X-ray counterpart, however, with a luminosity and temperature consistent with a normal supernova remnant of its size. The most likely classifications of the sources are as X-ray binaries. Although counting statistics are limited, over the 0.3–5.0 keV spectral band the data are well fit by simple absorbed power laws with luminosities in the 1038 − 1039 ergs s−1 range. -

February 14, 2015 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science Colleagues, College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting President’s Message Saturday, February 14, 2015 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science Colleagues, College of Southern Idaho. Public Star Party Follows at the It’s that time of year when obstacles appear in the sky. In particular, this year is Centennial Obs. loaded with fog. It got in the way of letting us see the dance of the Jovian moons late last month, and it’s hindered our views of other unique shows. Still, members Club Officers reported finding enough of a clear sky to let us see Comet Lovejoy, and some great photos by members are popping up on the Facebook page. Robert Mayer, President This month, however, is a great opportunity to see the benefit of something [email protected] getting in the way. Our own Chris Anderson of the Herrett Center has been using 208-312-1203 the Centennial Observatory’s scope to do work on occultation’s, particularly with asteroids. This month’s MVAS meeting on Feb. 14th will give him the stage to Terry Wofford, Vice President show us just how this all works. [email protected] The following weekend may also be the time the weather allows us to resume 208-308-1821 MVAS-only star parties. Feb. 21 is a great window for a possible star party; we’ll announce the location if the weather permits. However, if we don’t get that Gary Leavitt, Secretary window, we’ll fall back on what has become a MVAS tradition: Planetarium night [email protected] at the Herrett Center. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Flaming Star the Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405) in the Constellation Auriga Is a Surprisingly Colorful and Dramatic Emission/Reflection Nebula

WESTCHESTER AMATEUR ASTRONOMERS January 2016 Image Copyright: Mauri Rosenthal Flaming Star The Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405) in the constellation Auriga is a surprisingly colorful and dramatic emission/reflection nebula. In This Issue . The most prominent star in the image is the variable blue dwarf AE pg. 2 Events For January Aurigae, burning with sufficient intensity to knock electrons off pg. 3 Almanac the hydrogen molecules found in a cloud 5 light years across, pg. 4 Vivian Towers which in turn emit red light. The bluish gray area is not from ion- pg. 5 The Radio Sky ized Oxygen (as found in the Veil Nebula); rather it is mostly a pg. 11 Kepler cloud of carbon dust, which reflects the blue light from the nearby pg. 12 President’s Report star. The result is an emission/reflection nebula 1500 light years distant and accessible from the suburbs with a small telescope. Mauri Rosenthal imaged this from his backyard in Scarsdale with a guided Questar 3.5” telescope over two nights in November using CLS (broadband) and H-alpha (narrowband) filters. Total exposure time was 9.5 hours. SERVING THE ASTRONOMY COMMUNITY SINCE 1986 1 WESTCHESTER AMATEUR ASTRONOMERS January 2016 WAA January Lecture Club Dates 2016 “Light Pollution” Friday January 8th, 7:30pm 2016 Lecture Dates Leinhard Lecture Hall, January 8 June 3 February 5 Sept. 16 Pace University, Pleasantville, NY March 4 October 7 Charles Fulco will speak on light pollution, the Inter- April 1 November 4 national Dark-Sky Association and preserving our May 6 December 2 night sky. -

Ghost Supernova Remnants: Evidence for Pulsar Reactivation in Dusty Molecular Clouds?

Notas de Rsica NOTAS DE FÍSICA é uma pré-publicaçáo de trabalhos em Física do CBPF NOTAS DE FÍSICA is a series of preprints from CBPF Pedidos de cópias desta publicaçáfo devem ser enviados aos autores ou à: Requests for free copies of these reports should be addressed to: Divisão de Publicações do CBPF-CNPq Av. Wenceslau Braz, 71 • Fundos 22.290 - Rk> de Janeiro - RJ. Brasil CBPF-NF-034/83 GHOST SUPERNOVA RE WANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? by H.Heintzmann1 and M.Novello Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Físicas - CBPF/CNPq Rua Xavier Sigaud, 150 22290 - R1o de Janeiro, RJ - Brasil Mnstitut fOr Theoretische Physik der UniversUlt zu K0Tn, 5000 K01n 41, FRG Alemanha GHOST SUPERNOVA REMNANTS: EVIDENCE FOR PULSAR REACTIVATION IN DUSTY MOLECULAR CLOUDS? There is ample albeit ambiguous evidence in favour of a new model for pulsar evolution, according to which pulsars aay only function as regularly pulsed emitters if an accretion disc provides a sufficiently continuous return-current to the radio pulsar (neutron star). On its way through the galaxy the pulsar will consume the disc within some My and travel further (away from the galactic plane) some 100 My without functioning as a pulsar. Back to the galactic plane it may collide with a dense molecular cloud and turn-on for some ten thousand years as a RSntgen source through accretion. The response of the dusty cloud to the collision with the pulsar should resemble a super- nova remnant ("ghost supernova remnant") whereas the pulsar will have been endowed with a new disc, new angular momentum and a new magnetic field . -

Sejong Open Cluster Survey (SOS)-IV. the Young Open Clusters

Sejong Open Cluster Survey (SOS) - IV. The Young Open Clusters NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 Beomdu Lim1,5, Hwankyung Sung2, Michael S. Bessell3, Jinyoung S. Kim4, Hyeonoh Hur2, and Byeong-Gon Park1 [email protected] Received ; accepted Not to appear in Nonlearned J., 45. 1Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, 776 Daedeokdae-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-348, Korea 2Department of Astronomy and Space Science, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, arXiv:1502.00105v1 [astro-ph.SR] 31 Jan 2015 Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-747, Korea 3Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, MSO, Cotter Road, Weston, ACT 2611, Australia 4Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 N. Cherry Ave. Tucson, AZ 85721-0065, USA 5Corresponding author, Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology Research Fellow –2– ABSTRACT Young open clusters located in the outer Galaxy provide us with an oppor- tunity to study star formation activity in a different environment from the solar neighborhood. We present a UBVI and Hα photometric study of the young open clusters NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 that are situated toward the Galactic anticenter. Various photometric diagrams are used to select the members of the clusters and to determine the fundamental parameters. NGC 1624 and NGC 1931 are, on average, reddened by hE(B − V )i = 0.92 ± 0.05 and 0.74 ± 0.17 mag, respectively. The properties of the reddening toward NGC 1931 indicate an abnormal reddening law (RV,cl = 5.2 ± 0.3). Using the zero-age main se- quence fitting method we confirm that NGC 1624 is 6.0 ± 0.6 kpc away from the Sun, whereas NGC 1931 is at a distance of 2.3 ± 0.2 kpc.