Thacker and Ors Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIRST English 24 Final.Indd

Kuwait International Law School Journal Quarterly peer-reviewed Law Journal It is concerned with Publishing Legal and Sharia'a Studies and Research The first issue was published in March 2013 Volume 7 - Issue 1 - Serial Number 25 Jumada Al-Akhirah - Rajab /1440 - March 2019 Full text of the research is available in: Journal.Kilaw.edu.kw Kuwait International Law School Journal - Volume 5 - Issue 1 - Ser. No. 18 - Ramadan 1438 - June 2017 1 Editorial Board Editor - in - Chief Prof. Badria A. Al-Awadhi Managing Editor Dr. Ahmad Hamad Al-Faresi Editorial Consultant Prof. Abdelhamid M. El-baaly Prof. Seham Al-Foraih Prof. Yousri Elassar Prof. Ahmad A. Belal Prof. Magdi Shehab Prof. Amin Dawwas Dr. Abderasoul Abderidha The Journal Committee Dr. Ardit Memeti Dr. Farah Yassine Dr. Khaled Al Huwailah Dr. Ahmed Al Otaibi Dr. Yahya Al Nemer This is to certify that The Bachelor of Laws (LLB) programme offered at Kuwait International Law School is quality assured and has successfully passed a Curriculum Review with the following outcome The programme is well managed and complies with the European Standards and Guidelines (Part 1) 2015 and aligns with the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement: Law (2016). Review Conducted by The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) Douglas Blackstock, Chief Executive, Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, UK Valid until 30 September 2023 This is to certify that The Master of Laws (LLM) programme offered at Kuwait International Law School is quality assured and has successfully passed a Curriculum Review with the following outcome The programme is well managed and complies with the European Standards and Guidelines (Part 1) 2015 and aligns with the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement: Law (2016). -

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law

Cases and Materials on Criminal Law Michael T Molan Head ofthe Division ofLaw South Bank University Graeme Broadbent Senior Lecturer in Law Bournemouth University PETMAN PUBLISHING Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements x Table ofcases xi Table of Statutes xxiii 1 External elements of liability 1 Proof - Woolmington v DPP - Criminal Appeal Act 1968 - The nature of external elements - R v Deller - Larsonneur - Liability for omissions - R v Instan - R v Stone and Dobinson - Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner - R v Miller - R v Speck - Causation in law -Äv Pagett - Medical treatment - R v Sw/YA - R v Cheshire - The victim's reaction as a «ovtt.j öcto interveniens — Rv Blaue - R v Williams 2 Fault 21 Intention -Äv Hancock and Shankland - R v Nedrick - Criminal Justice Act 1967 s.8 - Recklessness -fiv Cunningham - R v Caldwell - R v Lawrence - Elliott \ C -R\ Reid -Rv Satnam; R v Kevra/ - Coincidence of acft« re«i and /nens rea - Thabo Meli v R - Transferred malice -Rv Pembliton -Rv Latimer 3 Liability without fault 56 Cundy v Le Cocq - Sherras v De Rutzen - SWef v Parsley - L/OT CA/« /4/£ v R - Gammon Ltd v Attomey-General for Hong Kong - Pharmaceutical Society ofGreat Britain v Storkwain 4 Factors affecting fault 74 Mistake - Mistake of fact negativing fault -Rv Tolson - DPP v Morgan - Mistake as to an excuse or justification - R v Kimber - R v Williams (Gladstone) - Beckford v R - Intoxication - DPP v Majewski - Rv Caldwell - Rv Hardie - R v Woods - R v O'Grady - Mental Disorder - M'Naghten's Case -Rv Kemp - Rv Sullivan - R v Hennessy -

Legal Right of Fetus: a Myth Or Fact

International Journal of Law, Humanities & Social Science Volume 1, Issue 1 (May 2017), P.P. 09-15 ISSN (ONLINE):2521-0793; ISSN (PRINT):2521-0785 Legal Right of Fetus: A Myth or Fact Md. Rafiqul Islam Hossaini LLB (Hon’s) UoL, UK; LLM (JnU); M. Phil (Researcher) (University of Dhaka) Abstract: Protection of human life has been extended to the protection of unborn child under the common law. In English law foetus has no legal right of its own until it is born alive and separated from its mother. The right to life of the unborn foetus is restricted or limited subject to the right to life of the mother. There are two types of legal liability for killing a child which subsequently dies after birth. They are: (1) Criminal liability (murder or manslaughter) and (2) Civil liability (medical negligence). Moreover, for killing an unborn child in the womb or damaging a foetus in the womb potential specific liabilities may arise both in the UK and Bangladesh. Apart from this, for considering the legal rights of foetus, the common law defence of necessity is a significant issue and a matter of academic debate. Keywords - legal right of fetus, criminal liability, civil liability, specific liabilities, defence of necessity Research Area: Law Paper Type: Research Paper 1. INTRODUCTION The word foetus or fetus is derived from the Latin word fētus, which means “offspring” or “bringing forth” or “hatching of young”. The literal meaning of foetus is “an unborn or unhatched vertebrate in the later stages of development showing the main recognizable features of the mature animal”. -

Mens Rea - Intention

Actus reus The actus reus in criminal law consists of all elements of a crime other than the state of mind of the defendant. In particular, actus reus may consist of: conduct, result, a state of affairsor an omission. Conduct - the conduct itself might be criminal. Eg. the conduct of lying under oath represents the actus reus of perjury. It does not matter that whether the lie is believed or if had any effect on the outcome of the case, the actus reus of the crime is complete upon the conduct. Examples of conduct crimes: Perjury Theft Making off without payment Rape Possession of drugs or a firearm Result - The actus reus may relate to the result of the act or omission of the defendant. The conduct itself may not be criminal, but the result of the conduct may be. Eg it is not a crime to throw a stone, but if it hits a person or smashes a window it could amount to a crime.Causation must be established in all result crimes. Examples of result crimes: Assault Battery ABH Wounding and GBH Murder & Manslaughter Criminal damage State of affairs - For state of affairs crimes the actus reus consists of 'being' rather than 'doing'. Eg 'being' drunk in charge of a vehicle (Duck v Peacock [1949] 1 All ER 318 Case summary) or 'being' an illegal alien (R v Larsonneur (1933) 24 Cr App R 74 case summary). Omission - Occassionally an omission can amount to the actus reus of a crime. The general rule regarding omissions is that there is no liability for a failure to act. -

Inchoate Offences

Consultation PaPer INCHOATE OFFENCES (lrC CP 48 – 2008) www.lawreform.ie coNsultatioN PaPer INCHOATE OFFENCES (lrc cP 48 – 2008) © coPyright law reform commission 2008 First Published February 2008 ISSN 1393-3140 i law reForM coMMissioN THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION’S ROLE the law reform commission is an independent statutory body established by the Law Reform Commission Act 1975. the commission’s principal role is to keep the law under review and to make proposals for reform, in particular by recommending the enactment of legislation to clarify and modernise the law. since it was established, the commission has published over 130 documents containing proposals for law reform and these are all available at www.lawreform.ie. Most of these proposals have led to reforming legislation. the commission’s role is carried out primarily under a Programme of law reform. its Third Programme of Law Reform 2008-2014 was prepared by the commission following broad consultation and discussion. in accordance with the 1975 act, it was approved by the government in december 2007 and placed before both houses of the oireachtas. the commission also works on specific matters referred to it by the attorney general under the 1975 act. since 2006, the commission’s role includes two other areas of activity, statute law restatement and the legislation directory. statute law restatement involves the administrative consolidation of all amendments to an act into a single text, making legislation more accessible. under the Statute Law (Restatement) Act 2002, where this text is certified by the attorney general it can be relied on as evidence of the law in question. -

Civil Aviation Authority V Griffiths

DCR CAA v Griffıths 169 Civil Aviation Authority v Griffiths District Court Christchurch CRI-2008-009-731 10, 18 June 2009 Judge Walsh Aviation — Offences — Fraudulent, misleading, or intentionally false statement — Criminal records report earlier provided to Civil Aviation Authority — Whether subsequent non-disclosure of convictions dishonest — Civil Aviation Act 1990, s 46(1)(a). In late 2005 the defendant, Mr Griffiths, who had three drink-driving convictions in 1993, 1996 and 1997 respectively, intended enrolling for training as a commercial pilot. The aviation school in question made a written inquiry to the Civil Aviation Authority (the CAA) as to his eligibility for a licence in light of his convictions, and enclosed a copy of a criminal conviction report obtained from the Ministry of Justice which detailed the convictions. The response of the CAA was that a conviction-free period of five years before an application for a licence was considered favourably. Subsequently, in late 2006, when undergoing an assessment by an aviation medical examiner appointed under the Civil Aviation Act 1990 (the Act), Mr Griffiths disclosed only one conviction and was charged under the Act with making a fraudulent, misleading or intentionally false statement for the purpose of obtaining a medical certificate under the Act. In his defence Mr Griffiths claimed that he had no intention to deceive but believed that the CAA was already aware of his convictions and that in any event he inferred from the response of the CAA to his earlier inquiry that a conviction older than five years was not considered relevant. Held (dismissing the information) 1 For proof of a fraudulent or intentionally false statement it had to be shown that the statement was dishonest in the sense of being false or not true to the knowledge of the defendant and the defendant intended to make the statement or was reckless as to it being made. -

![Arxiv:2106.04235V1 [Cs.AI] 8 Jun 2021 H](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9190/arxiv-2106-04235v1-cs-ai-8-jun-2021-h-5399190.webp)

Arxiv:2106.04235V1 [Cs.AI] 8 Jun 2021 H

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definitions of intent suitable for algorithms Hal Ashton Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Intent modifies an actor's culpability of many types wrongdoing. Autonomous Algorithmic Agents have the capability of causing harm, and whilst their current lack of legal personhood precludes them from committing crimes, it is useful for a number of parties to understand under what type of intentional mode an algorithm might transgress. From the perspective of the creator or owner they would like ensure that their algorithms never intend to cause harm by doing things that would otherwise be labelled criminal if com- mitted by a legal person. Prosecutors might have an interest in understanding whether the actions of an algorithm were internally intended according to a transparent definition of the concept. The presence or absence of intention in the algorithmic agent might inform the court as to the complicity of its owner. This article introduces definitions for direct, oblique (or indirect) and ulterior intent which can be used to test for intent in an algorithmic actor. Keywords Intent · Causality · Autonomous Agents · AI Crime · AI Ethics 1 Introduction The establishment of criminal intent, the volitional component of mens rea in the someone accused of committing a crime, is a necessary task in proving that a crime was committed. An autonomous algorithm with agency can perform actions which would considered criminal (actus reus) if a human with sufficient mens rea performed them. For brevity in this article we will follow Abbott and Supported by EPSRC arXiv:2106.04235v1 [cs.AI] 8 Jun 2021 H. -

KILINDO and PAYET V REPUBLIC (2011) SLR 283 N Gabriel

KILINDO AND PAYET v REPUBLIC (2011) SLR 283 N Gabriel for appellant one S Freminot for appellant two D Esparon for the defendant Judgment delivered on 2 September 2011 by Domah J The two appellants stood trial for murder under section 193 of the Penal Code before a judge and a jury who returned a verdict of guilty against both. They were each sentenced to life imprisonment. They appealed against their conviction. THE APPEAL OF JEAN-PAUL KILINDO Appellant Jean-Paul Kilindo has put up the following grounds of appeal: 1. The trial judge erred in that he did not put to the jury sufficiently or at all the case of the appellant. 2. The trial judge did not put to the jury the fact that the appellant could be convicted to a lesser charge of manslaughter. Both grounds were taken together in course of argument of counsel for the appellant. The main thrust of his argument was that appellant Kilindo had joined his confederate in crime not for the purposes of causing anybody's death but simply for the purposes of burglary: i.e. looking for, breaking a safe and stealing therefrom. At one stage, appellant Kilindo insisted that they should leave. He, indeed, was getting ready to leave when he saw the lights of an approaching vehicle. In the circumstances, counsel for Kilindo urged before us, it was the duty of the judge to dwell upon the limited participation of appellant Kilindo in the actus reus of the killing as well as his lack of mens rea which fell short of the malice aforethought required by law for murder. -

Criminal Law

Criminal Law CONTENTS PAGES CHAPTER 1 OUTCOMES 2 INTRODUCTION TO CRIMINAL LAW 3-7 ACTUS REUS 8-16 MENS REA 17-31 STRICT LIABILITY 32-35 INCHOATE OFFENCES 36-45 CHAPTER 2 OUTCOMES 46 NON-FATAL OFFENCES AGAINST THE PERSON 47-57 FATAL OFFENCES 58-68 PROPERTY OFFENCES 69-80 CHAPTER 3 OUTCOMES 81 GENERAL DEFENCES 82-94 OVERVIEW OF POLICE POWERS 95-105 2 Chapter 1 Learning outcomes After studying this chapter you should understand the following main points: þ the principles of criminal liability; þ the general rule in relation to actus reus; þ the rules on causation; þ the different levels of mens rea; and þ what is meant by an incomplete offence and the justification for punishing those that do not complete and offence. 1.1 Introduction to Criminal Law 1. Introduction The criminal law is not just a set of rules; it is underpinned by ethical and political principles created to ensure justice for the individual and protection to the community. If the application of a particular rule to a case results in the acquittal of a dangerous person, or convicts someone that is not dangerous or blameworthy according to ordinary standards, something has gone wrong. Crimes are distinguished from other acts or omissions which may give rise to legal proceedings by the prospect of punishment. It is this prospect which separates the criminal law from the law of contract and tort and other aspects of the civil law. The threshold at which the criminal law intervenes is when the conduct in question has a sufficiently serious social impact to justify the state, rather than (in the case of breach of contract or trespass) the individual affected, taking on the case of the injured party. -

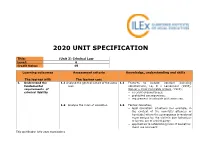

2020 Unit Specification

2020 UNIT SPECIFICATION Title: (Unit 3) Criminal Law Level: 6 Credit Value: 15 Learning outcomes Assessment criteria Knowledge, understanding and skills The learner will: The learner can: 1. Understand the 1.1 Analyse the general nature of the actus 1.1 Features to include: conduct (including fundamental reus voluntariness, i.e, R v Larsonneur (1933), requirements of Winzar v Chief Constable of Kent (1983); criminal liability • relevant circumstances; • prohibited consequences; • requirement to coincide with mens rea. 1.2 Analyse the rules of causation 1.2 Factual causation; • legal causation: situations (for example, in the context of the non-fatal offences or homicide) where the consequence is rendered more serious by the victim’s own behaviour or by the act of a third party; • approaches to establishing rules of causation: mens rea approach; This specification is for 2020 examinations • policy approach; • relevant case law to include: R v White (1910), R v Jordan (1956) R v Cheshire (1991), R v Blaue (1975), R v Roberts (1971), R v Pagett (1983), R v Kennedy (no 2) (2007), R v Wallace (Berlinah) (2018) and developing caselaw. 1.3 Circumstances in which an omission gives rise to 1.3 Analyse the status of omissions liability; • validity of the act/omission distinction; • rationale for restricting liability for omissions; • relevant case law to include: R v Pittwood (1902), R v Instan (1977), R v Miller (1983), Airedale NHS Trust v Bland (1993) Stone & Dobinson (1977), R v Evans (2009) and developing caselaw. 1.4 S8 Criminal Justice Act 1967; 1.4 Analyse the meaning of intention • direct intention; • oblique intention: definitional interpretation; • evidential interpretation; • implications of each interpretation; • concept of transferred malice; • relevant case law to include: R v Steane (1947), Chandler v DPP (1964), R v Nedrick (1986), R v Woollin (1999), Re A (conjoined twins) (2000), R v Matthews and Alleyne (2003), R v Latimer (1886), R v Pembliton (1874), R v Gnango (2011) and developing caselaw. -

Homicide: Murder and Involuntary Manslaughter

RepoRt HOMICIDE: muRdeR and involuntaRy manslaughteR (lRc 87 – 2008) report HOMICIDE: murder aNd iNvoluNtary maNslaughter (lrc 87 – 2008) © copyright law reform commission 2008 First published January 2008 ISSN 1393-3132 i law reForm commissioN THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION’S ROLE the law reform commission is an independent statutory body established by the Law Reform Commission Act 1975. the commission’s principal role is to keep the law under review and to make proposals for reform, in particular by recommending the enactment of legislation to clarify and modernise the law. since it was established, the commission has published over 130 documents containing proposals for law reform and these are all available at www.lawreform.ie. most of these proposals have led to reforming legislation. the commission’s role is carried out primarily under a programme of law reform. its Third Programme of Law Reform 2008-2014 was prepared by the commission following broad consultation and discussion. in accordance with the 1975 act, it was approved by the government in december 2007 and placed before both houses of the oireachtas. the commission also works on specific matters referred to it by the attorney general under the 1975 act. since 2006, the commission’s role includes two other areas of activity, statute law restatement and the legislation directory. statute law restatement involves the administrative consolidation of all amendments to an act into a single text, making legislation more accessible. under the Statute Law (Restatement) Act 2002, where this text is certified by the attorney general it can be relied on as evidence of the law in question. -

Law for Ethnographers

MIO0010.1177/2059799117720607Methodological InnovationsElliott and Fleetwood 720607research-article2017 Article Methodological Innovations 2017, Vol. 10(1) 1-13 Law for ethnographers © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799117720607DOI: 10.1177/2059799117720607 mio.sagepub.com Tracey Elliott1 and Jennifer Fleetwood2 Abstract Despite a long history of ethnographic research on crime, ethnographers have shied away from examining the law as it relates to being present at, witnessing and recording illegal activity. However, knowledge of the law is an essential tool for researchers and the future of ethnographic research on crime. This article reviews the main relevant legal statutes in England and Wales and considers their relevance for contemporary ethnographic research. We report that researchers have no legal responsibility to report criminal activity (with some exceptions). The circumstances under which legal action could be taken to seize research data are specific and limited, and respondent’s privacy is subject to considerable legal protection. Our review gives considerable reason to be optimistic about the future of ethnographic research. Keywords law, ethnography, confidentiality Introduction Ethnographers of crime and deviance have long trod the thin for researchers to be granted legal privileges to guarantee line between observing and participating in criminal activi- respondents’ confidentiality, as occurs for government-funded ties, so it is somewhat surprising