The Law Commissions Act 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Recognizing Making Intimacy Vincent Tajiri Even Hotter!

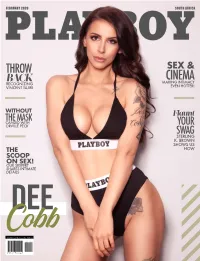

FEBRUARY 2020 SOUTH AFRICA THROW SEX & BACK CINEMA RECOGNIZING MAKING INTIMACY VINCENT TAJIRI EVEN HOTTER! WITHOUT Flaunt THE MASK CANDID WITH YOUR ORVILLE PECK SWAG STERLING K. BROWN SHOWS US THE HOW SCOOP ON SEX! OUR SEXPERT SHARES INTIMATE DETAILS Dee Cobb WWW.PLAYBOY.CO.ZA R45.00 20019 9 772517 959409 EVERY. ISSUE. EVER. The complete Playboy archive Instant access to every issue, article, story, and pictorial Playboy has ever published – only on iPlayboy.com. VISIT PLAYBOY.COM/ARCHIVE SOUTH AFRICA Editor-in-Chief Dirk Steenekamp Associate Editor Jason Fleetwood Graphic Designer Koketso Moganetsi Fashion Editor Lexie Robb Grooming Editor Greg Forbes Gaming Editor Andre Coetzer Tech Editor Peter Wolff Illustrations Toon53 Productions Motoring Editor John Page Senior Photo Editor Luba V Nel ADVERTISING SALES [email protected] for more information PHONE: +27 10 006 0051 MAIL: PO Box 71450, Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021 Ƶč%./0(++.ǫ(+'ć+1.35/""%!.'Čƫ*.++/0.!!0Ē+1.35/ǫ+1(!2. ČĂāĊā EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.playboy.co.za FACEBOOK: facebook.com/playboysouthafrica TWITTER: @PlayboyMagSA INSTAGRAM: playboymagsa PLAYBOY ENTERPRISES, INTERNATIONAL Hugh M. Hefner, FOUNDER U.S. PLAYBOY ǫ!* +$*Čƫ$%!"4!10%2!þ!. ƫ++,!.!"*!.Čƫ$%!"ƫ.!0%2!þ!. Michael Phillips, SVP, Digital Products James Rickman, Executive Editor PLAYBOY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING !!*0!(Čƫ$%!"ƫ+))!.%(þ!.Ē! +",!.0%+*/ Hazel Thomson, Senior Director, International Licensing PLAYBOY South Africa is published by DHS Media House in South Africa for South Africa. Material in this publication, including text and images, is protected by copyright. It may not be copied, reproduced, republished, posted, broadcast, or transmitted in any way without written consent of DHS Media House. -

University of Dundee the Origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal Smith, Mark

University of Dundee The origins of the Jimmy Savile scandal Smith, Mark; Burnett, Ros Published in: International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy DOI: 10.1108/IJSSP-03-2017-0029 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Smith, M., & Burnett, R. (2018). The origins of the Jimmy Savile scandal. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 38(1/2), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-03-2017-0029 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 The origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal Dr Mark Smith, University of Edinburgh (Professor of Social Work, University of Dundee from September 2017) Dr Ros Burnett, University of Oxford Abstract Purpose The purpose of this paper is to explore the origins of the Jimmy Savile Scandal in which the former BBC entertainer was accused of a series of sexual offences after his death in 2011. -

Gigabit-Broadband in the UK: Government Targets and Policy

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8392, 30 April 2021 Gigabit-broadband in the By Georgina Hutton UK: Government targets and policy Contents: 1. Gigabit-capable broadband: what and why? 2. Gigabit-capable broadband in the UK 3. Government targets 4. Government policy: promoting a competitive market 5. Policy reforms to help build gigabit infrastructure Glossary www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Gigabit-broadband in the UK: Government targets and policy Contents Summary 3 1. Gigabit-capable broadband: what and why? 5 1.1 Background: superfast broadband 5 1.2 Do we need a digital infrastructure upgrade? 5 1.3 What is gigabit-capable broadband? 7 1.4 Is telecommunications a reserved power? 8 2. Gigabit-capable broadband in the UK 9 International comparisons 11 3. Government targets 12 3.1 May Government target (2018) 12 3.2 Johnson Government 12 4. Government policy: promoting a competitive market 16 4.1 Government policy approach 16 4.2 How much will a nationwide gigabit-capable network cost? 17 4.3 What can a competitive market deliver? 17 4.4 Where are commercial providers building networks? 18 5. Policy reforms to help build gigabit infrastructure 20 5.1 “Barrier Busting Task Force” 20 5.2 Fibre broadband to new builds 22 5.3 Tax relief 24 5.4 Ofcom’s work in promoting gigabit-broadband 25 5.5 Consumer take-up 27 5.6 Retiring the copper network 28 Glossary 31 ` Contributing Authors: Carl Baker, Section 2, Broadband coverage statistics Cover page image copyright: Blue Fiber by Michael Wyszomierski. -

The Constitution and Revenge Porn

Pace Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 Fall 2014 Article 8 Symposium: Social Media and Social Justice September 2014 The Constitution and Revenge Porn John A. Humbach Pace University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal Remedies Commons Recommended Citation John A. Humbach, The Constitution and Revenge Porn, 35 Pace L. Rev. 215 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol35/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Constitution and Revenge Porn John A. Humbach* “Many are those who must endure speech they do not like, but that is a necessary cost of freedom.”1 Revenge porn refers to sexually explicit photos and videos that are posted online or otherwise disseminated without the consent of the persons shown, generally in retaliation for a romantic rebuff.2 The problem of revenge porn seems to have emerged fairly recently,3 no doubt facilitated by the widespread practice of sexting.4 In sexting, people make and send explicit pictures of themselves using digital devices.5 These devices, in their very nature, permit the pictures to be easily shared with the entire online world. Although the move from sexting to revenge porn might seem as inevitable as the shifting winds * Professor of Law at Pace University School of Law. -

Developing a National Action Plan for Eliminating Sex Trafficking

Developing a National Action Plan for Eliminating Sex Trafficking Final Report August 16, 2010 Prepared by: Michael Shively, Ph.D. Karen McLaughlin Rachel Durchslag Hugh McDonough Dana Hunt, Ph.D. Kristina Kliorys Caroline Nobo Lauren Olsho, Ph.D. Stephanie Davis Sara Collins Cathy Houlihan SAGE Rebecca Pfeffer Jessica Corsi Danna Mauch, Ph.D Abt Associates Inc. 55 Wheeler St. Cambridge, MA 02138 www.abtassoc.com Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................xii Overview of the Report.............................................................................................................xiv Chapter 1: Overview ............................................................................................................................1 Project Background......................................................................................................................3 Targeting Demand .......................................................................................................................3 Assumptions about the Scope and Focus of the National Campaign...........................................5 The National Action Plan.............................................................................................................6 Scope of the Landscape Assessment............................................................................................7 -

Vision for Change: Acceptance Without Exception for Trans People

A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people 2017-2022 A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people Produced by Stonewall Trans Advisory Group Published by Stonewall [email protected] www.stonewall.org.uk/trans A VISION FOR CHANGE Acceptance without exception for trans people 2017-2022 CONTENTS PAGE 5 INTRODUCTION FROM STONEWALL’S TRANS ADVISORY GROUP PAGE 6 INTRODUCTION FROM RUTH HUNT, CHIEF EXECUTIVE, STONEWALL PAGE 7 HOW TO READ THIS DOCUMENT PAGE 8 A NOTE ON LANGUAGE PAGE 9 EMPOWERING INDIVIDUALS: enabling full participation in everyday and public life by empowering trans people, changing hearts and minds, and creating a network of allies PAGE 9 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o Role models o Representation of trans people in public life o Representation of trans people in media o Diversity of experiences o LGBT communities o Role of allies PAGE 11 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 12 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 14 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 16 TRANSFORMING INSTITUTIONS: improving services and workplaces for trans people PAGE 16 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o Children, young people and education o Employment o Faith o Hate crime, the Criminal Justice System and support services o Health and social care o Sport PAGE 20 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 21 −−WHAT SERVICE PROVIDERS CAN DO PAGE 26 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 28 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 30 CHANGING LAWS: ensuring equal rights, responsibilities and legal protections for trans people PAGE 30 −−THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: o The Gender Recognition Act o The Equality Act o Families and marriage o Sex by deception o Recording gender o Asylum PAGE 32 −−VISION FOR CHANGE PAGE 33 −−STONEWALL’S RESPONSE PAGE 34 −−WHAT OTHERS CAN DO PAGE 36 GETTING INVOLVED PAGE 38 GLOSSARY INTRODUCTION FROM STONEWALL’S TRANS ADVISORY GROUP The UK has played an While many of us benefited from the work to give a voice to all parts of trans successes of this time, many more communities, and we are determined important role in the did not. -

Achter De Schermen Achter Een Verkennend Onderzoek Naar Downloaders Van Kinderporno

In dit verkennende onderzoek wordt getracht enig licht te werpen op het fenomeen Achter deschermen downloaden van kinderporno en met name op de persoon van downloaders. Wat is in de literatuur en bij opsporings- en hulpverleningsinstanties bekend over de achtergronden - geslacht, leeftijd, etniciteit - en motieven van downloaders? Gaat het uitsluitend om het downloaden en verzamelen van afbeeldingen of speelt Achter de schermen een seksuele voorkeur voor kinderen ook mee? Hoe functioneert de markt van vraag en aanbod wat betreft kinderporno op het internet en welke rol spelen Anton vanWijk,AnnemiekNieuwenhuisenAngeline Smeltink Een verkennend onderzoek naar downloaders van kinderporno downloaders: zijn zij enkel afnemers of ook producenten van kinderporno? Ook de manieren waarop downloaders opereren en proberen uit handen te blijven van de politie passeren de revue. Verder wordt beschreven wat bekend is over de omvang van het kinderporno- grafi sch beeldmateriaal dat op het internet te vinden is. Wat is de leeftijd van de afgebeelde kinderen en om welke seksuele poses gaat het? Uit het onder- zoek blijkt dat er verschillende profi elen van downloaders zijn te onderscheiden. Die profi elen behoeven door middel van vervolgonderzoek nog nadere inkleuring en toetsing. Voor de opsporing is het van groot belang om meer zicht te krijgen op de besloten netwerken op internet waar vaak grove vormen van kinderporno worden verhandeld en uitgewisseld. Anton van Wijk Annemiek Nieuwenhuis ISBN 978-90-75116-56-4 Angeline Smeltink Achter de schermen Achter de schermen Een verkennend onderzoek naar downloaders van kinderporno Anton van Wijk Annemiek Nieuwenhuis Angeline Smeltink In opdracht van Programma Politie & Wetenschap Omslagillustratie en vormgeving Marcel Grotens Drukwerk GVO Drukkers & Vormgevers B.V. -

Organisational Sex Offenders and 'Institutional Grooming': Lessons from the Savile and Other Inquiries

Organisational Sex Offenders and 'Institutional Grooming': Lessons from the Savile and Other Inquiries McAlinden, A-M. (2018). Organisational Sex Offenders and 'Institutional Grooming': Lessons from the Savile and Other Inquiries. In M. Erooga (Ed.), Protecting Children and Adults from Abuse After Savile: What Organizations and Institutions Need to do London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Published in: Protecting Children and Adults from Abuse After Savile: What Organizations and Institutions Need to do Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2018 Jessica Kingsley Publishing.This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 FINAL AUTHOR VERSION: McAlinden, A.-M. (2018), ‘Organisational Sex Offenders and “Institutional Grooming’: Lessons from the Savile and Other Inquiries’, in M. -

Image-Based Sexual Abuse Risk Factors and Motivators Vasileia

RUNNING HEAD: IBSA FACTORS AND MOTIVATORS iPredator: Image-based Sexual Abuse Risk Factors and Motivators Vasileia Karasavva A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Psychology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Vasileia Karasavva IBSA FACTORS AND MOTIVATORS i Abstract Image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) can be defined as the non-consensual sharing or threatening to share of nude or sexual images of another person. This is one of the first studies examining how demographic characteristics (gender, sexual orientation), personality traits (Dark Tetrad), and attitudes (aggrieved entitlement, sexual entitlement, sexual image abuse myth acceptance) predict the likelihood of engaging in IBSA perpetration and victimization. In a sample of 816 undergraduate students (72.7% female and 23.3% male), approximately 15% of them had at some point in their life, distributed and/or threatened to distribute nude or sexual pictures of someone else without their consent and 1 in 3 had experienced IBSA victimization. Higher psychopathy or narcissism scores were associated with an increased likelihood of having engaged in IBSA perpetration. Additionally, those with no history of victimization were 70% less likely to have engaged in IBSA perpetration compared to those who had experienced someone disseminating their intimate image without consent themselves. These results suggest that a cyclic relationship between IBSA victimization exists, where victims of IBSA may turn to perpetration, and IBSA perpetrators may leave themselves vulnerable to future victimization. The challenges surrounding IBSA policy and legislation highlight the importance of understanding the factors and motivators associated with IBSA perpetration. -

Revenge Porn and the ACLU's Inconsistent Approach

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 7 Spring 1-2020 Revenge Porn and the ACLU’s Inconsistent Approach Elena Lentz Notes Editor, IJLSE Vol.8; J.D. 2020, Ind. Univ. Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Publication Citation 8 Ind. J.L. & Soc. Equality 155 (2020). This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Revenge Porn and the ACLU’s Inconsistent Approach Elena Lentz* INTRODUCTION As of 2016, 10.4 million Americans have been threatened with or been the victim of nonconsensual pornography, more commonly known as revenge porn.1 Of these victims, eighty percent are women.2 Furthermore, the pervasive and anonymous nature of the internet has encouraged the growth of revenge porn and allowed for repeated victimization. As a result, thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia have criminalized revenge porn.3 Several other states have tried to pass revenge porn laws and faced First Amendment challenges. In the twelve states that do not criminalize revenge porn, victims often must rely on either tort law, copyright law, or the federal cyberstalking statute.4 Yet, these existing frameworks are often ill-fitted for the unique issues raised by revenge porn. -

Defamation in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 37/14 21 March 2014 NIAR 95-14 Michael Potter Defamation in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland Nothing in this paper constitutes legal advice or should be used as a replacement for such 1 Introduction The Committee for Finance and Personnel commissioned background research into the approaches adopted by the Scottish Parliament and the Oireachtas with respect to defamation law1. This paper supplements Briefing Paper 90/13 ‘The Defamation Act 2013’2, presented to the Committee for Finance and Personnel on 26 June 20133. The paper considers defamation law in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland in the light of legislative change in England and Wales brought about by the Defamation Act 2013. 1 Meeting of the Committee for Finance and Personnel 3 July 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/Finance/minutes/20130703.pdf. 2 Research and Information Service Briefing Paper 90/13 The Defamation Act 2013 21 June 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/RaISe/Publications/2013/finance_personnel/9013.pdf. 3 Meeting of the Committee for Finance and Personnel 26 June 2013: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/Finance/minutes/20130626.pdf. Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 95-14 Briefing Paper 2 Defamation Law in England and Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland The basis of defamation law in all four jurisdictions is in common law. Legislation has codified certain aspects of defamation in each case, the more recent -

The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology

The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology Joanna Williams The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology Joanna Williams First published June 2020 © Civitas 2020 55 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-912581-08-5 Independence: Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society is a registered educational charity (No. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee (No. 04023541). Civitas is financed from a variety of private sources to avoid over-reliance on any single or small group of donors. All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting the advancement of learning. The views expressed are those of the authors, not of the Institute. Typeset by Typetechnique Printed in Great Britain by 4edge Limited, Essex iv Contents Author vi Summary vii Introduction 1 1. Changing attitudes towards sex and gender 3 2. The impact of transgender ideology 17 3. Ideological capture 64 Conclusions 86 Recommendations 88 Bibliography 89 Notes 97 v Author Joanna Williams is director of the Freedom, Democracy and Victimhood Project at Civitas. Previously she taught at the University of Kent where she was Director of the Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Joanna is the author of Women vs Feminism (2017), Academic Freedom in an Age of Conformity (2016) and Consuming Higher Education, Why Learning Can’t Be Bought (2012). She co-edited Why Academic Freedom Matters (2017) and has written numerous academic journal articles and book chapters exploring the marketization of higher education, the student as consumer and education as a public good.