Cambridge Companions Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Education and Class Formation in Early Judaism

COLONIAL EDUCATION AND CLASS FORMATION IN EARLY JUDAISM: A POSTCOLONIAL READING by Royce Manojkumar Victor Bachelor of Science, 1988 Calicut University, Kerala, India Bachelor of Divinity, 1994 United Theological College Bangalore, India Master of Theology, 1999 Senate of Serampore College Serampore, India Dissertation Presented to the Faulty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, Texas U.S.A. May 2007 ii iii © 2007 by Royce Manojkumar Victor Acknowledgments It is a delight to have the opportunity to thank the people who have helped me with the writing of this dissertation. Right from beginning to the completion of this study, Prof. Leo Perdue, my dissertation advisor and my guru persevered with me, giving apt guidance and judicious criticism at every stage. He encouraged me to formulate my own questions, map out my own quest, and seek the answers that would help me understand and contextualize my beliefs, practices, and identity. My profuse thanks to him. I also wish to thank Prof. David Balch and Prof. Carolyn Osiek, my readers, for their invaluable comments and scholarly suggestions to make this study a success. I am fortunate to receive the wholehearted support and encouragement of Bishop George Isaac in this endeavor, and I am filled with gratitude to him. With deep sense of gratitude, I want to acknowledge the inestimable help and generous support of my friends from the Grace Presbytery of PC(USA), who helped me to complete my studies in the United States. In particular, I wish to thank Rev. -

Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: a Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=Trgf II F646a Anton Bierl

BIERL, ANTON, Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of a New Dramatic Papyrus , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 31:4 (1990:Winter) p.353 Dionysus, Wine, and Tragic Poetry: A Metatheatrical Reading of P.Koln VI 242A=TrGF II F646a Anton Bierl EW DRAMATIC PAPYRUS1 confronts interpreters with many ~puzzling questions. In this paper I shall try to solve some of these by applying a new perspective to the text. I believe that this fragment is connected with a specific literary feature of drama especially prominent in the bnal decades of the bfth century B.C., viz. theatrical self-consciousness and the use of Dionysus, the god of Athenian drama, as a basic symbol for this tendency. 2 The History of the Papyrus Among the most important papyri brought to light by Anton Fackelmann is an anthology of Greek prose and poetry, which includes 19 verses of a dramatic text in catalectic anapestic tetrameters. Dr Fackelmann entrusted the publication of this papyrus to Barbel Kramer of the University of Cologne. Her editio princeps appeared in 1979 as P. Fackelmann 5. 3 Two years later the verses were edited a second time by Richard Kannicht and Bruno Snell and integrated into the Fragmenta Adespota in 1 This papyrus has already been treated by the author in Dionysos und die griechische Trag odie. Politische und 'metatheatralische' Aspekte im Text (Tiibingen 1991: hereafter 'Bieri') 248-53. The interpretation offered here is an expansion of my earlier provisional comments in the Appendix, presenting fragments of tragedy dealing with Dionysus. 2 See C. -

A. W. Schlegel and the Nineteenth-Century Damnatio of Euripides Ernst Behler

BEHLER, ERNST, A. W. Schlegel and the Nineteenth-Century "Damnatio" of Euripides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:4 (1986:Winter) p.335 A. W. Schlegel and the Nineteenth-Century Damnatio of Euripides Ernst Behler N HIS 1802-04 Berlin lectures on aesthetics, August Wilhelm Schle I gel claimed that his younger brother Friedrich (in his essay On the Study of Greek Poetry U795]), had been the first in the modern age to discern the "immeasurable gulf" separating Euripides from Aeschylus and Sophocles, thereby reviving an attitude the Greeks themselves had assumed towards the poet. The elder Schlegel noted that certain contemporaries of Euripides felt the "deep decline" both in his tragic art and in the music of the time: Aristophanes, with his unrelenting satire, had been assigned by God as Euripides' "eternal scourge"; 1 Plato, in reproaching the poets for fostering the passionate state of mind through excessive emotionalism, actually pointed to Euripides (SK I 40). Schlegel believed that his younger brother's observation of the profound difference between Euripides and the two other Greek tragedians was an important intuition that required detailed critical and comparative analysis for sufficient development (SK II 359). By appropriating this task as his own, August Wilhelm Schlegel inaugurated a phenomenon that we may describe as the nineteenth-century damnatio of Euripides. The condemnation of Euripides by these early German romantics was no extravagant and isolated moment in their critical activity: it constituted a central event in the progressive formation of a new literary theory. Their pronouncements must be seen in the context of a larger movement, towards the end of the eighteenth century, that transformed the critical scene in Europe: the fall of the classicist doctrine and the rise of the new literary theory of romanticism. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Who Was Protagoras? • Born in Abdêra, an Ionian Pólis in Thrace

Recovering the wisdom of Protagoras from a reinterpretation of the Prometheia trilogy Prometheus (c.1933) by Paul Manship (1885-1966) By: Marty Sulek, Ph.D. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy For: Workshop In Multidisciplinary Philanthropic Studies February 10, 2015 Composed for inclusion in a Festschrift in honour of Dr. Laurence Lampert, a Canadian philosopher and leading scholar in the field of Nietzsche studies, and a professor emeritus of Philosophy at IUPUI. Adult Content Warning • Nudity • Sex • Violence • And other inappropriate Prometheus Chained by Vulcan (1623) themes… by Dirck van Baburen (1595-1624) Nietzsche on Protagoras & the Sophists “The Greek culture of the Sophists had developed out of all the Greek instincts; it belongs to the culture of the Periclean age as necessarily as Plato does not: it has its predecessors in Heraclitus, in Democritus, in the scientific types of the old philosophy; it finds expression in, e.g., the high culture of Thucydides. And – it has ultimately shown itself to be right: every advance in epistemological and moral knowledge has reinstated the Sophists – Our contemporary way of thinking is to a great extent Heraclitean, Democritean, and Protagorean: it suffices to say it is Protagorean, because Protagoras represented a synthesis of Heraclitus and Democritus.” Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 2.428 Reappraisals of the authorship & dating of the Prometheia trilogy • Traditionally thought to have been composed by Aeschylus (c.525-c.456 BCE). • More recent scholarship has demonstrated the play to have been written by a later, lesser author sometime in the 430s. • This new dating raises many questions as to what contemporary events the trilogy may be referring. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note : Geographical landmarks are listed under the proper name itself: for “Cape Sepias” or “Mt. Athos” see “Sepias” or “Athos.” When a people and a toponym share the same base, see under the toponym: for “Thessalians” see “Thessaly.” Romans are listed according to the nomen, i.e. C. Julius Caesar. With places or people mentioned once only, discretion has been used. Abdera 278 Aeaces II 110, 147 Abydus 222, 231 A egae 272–273 Acanthus 85, 207–208, 246 Aegina 101, 152, 157–158, 187–189, Acarnania 15, 189, 202, 204, 206, 251, 191, 200 347, 391, 393 Aegium 377, 389 Achaia 43, 54, 64 ; Peloponnesian Aegospotami 7, 220, 224, 228 Achaia, Achaian League 9–10, 12–13, Aemilius Paullus, L. 399, 404 54–56, 63, 70, 90, 250, 265, 283, 371, Aeolis 16–17, 55, 63, 145, 233 375–380, 388–390, 393, 397–399, 404, Aeschines 281, 285, 288 410 ; Phthiotic Achaia 16, 54, 279, Aeschylus 156, 163, 179 286 Aetoli Erxadieis 98–101 Achaian War 410 Aetolia, Aetolian League 12, 15, 70, Achaius 382–383, 385, 401 204, 250, 325, 329, 342, 347–348, Acilius Glabrio, M. 402 376, 378–380, 387, 390–391, 393, Acragas 119, COPYRIGHTED165, 259–261, 263, 266, 39MATERIAL6–397, 401–404 352–354, 358–359 Agariste 113, 117 Acrocorinth 377, 388–389 Agathocles (Lysimachus ’ son) 343, 345 ; Acrotatus 352, 355 (King of Sicily) 352–355, 358–359; Actium 410, 425 (King of Bactria) 413–414 Ada 297 Agelaus 391, 410 A History of Greece: 1300 to 30 BC, First Edition. Victor Parker. -

Athenaeus' Reading of the Aulos Revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616E–617F)

The Journal of Hellenic Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS Additional services for The Journal of Hellenic Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e–617f) Pauline A. Leven The Journal of Hellenic Studies / Volume 130 / November 2010, pp 35 - 48 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030, Published online: 19 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0075426910000030 How to cite this article: Pauline A. Leven (2010). New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e– 617f). The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 130, pp 35-48 doi:10.1017/S0075426910000030 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS, IP address: 147.91.1.45 on 23 Sep 2013 Journal of Hellenic Studies 130 (2010) 35−47 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030 NEW MUSIC AND ITS MYTHS: ATHENAEUS’ READING OF THE AULOS REVOLUTION (DEIPNOSOPHISTAE 14.616E−617F) PAULINE A. LEVEN Yale University* Abstract: Scholarship on the late fifth-century BC New Music Revolution has mostly relied on the evidence provided by Athenaeus, the pseudo-Plutarch De musica and a few other late sources. To this date, however, very little has been done to understand Athenaeus’ own role in shaping our understanding of the musical culture of that period. This article argues that the historical context provided by Athenaeus in the section of the Deipnosophistae that cites passages of Melanippides, Telestes and Pratinas on the mythology of the aulos (14.616e−617f) is not a credible reflection of the contemporary aesthetics and strategies of the authors and their works. -

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions Inaugural Colloquium of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network (HCARN) Department of Classics, University of Reading (UK) 15-17 April 2016 ABSTRACTS All conference sessions will be held in Lecture Room G 15, Henley Business School, University of Reading Whiteknights Campus. Baralay, Supratik (University of Oxford) The Arsakids between the Seleucids and the Achaemenids Abstract pending. Bordeaux, Olivier (Paris-Sorbonne) Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics: Methodologies, new research and limits Numismatics is one of the leading fields in Hellenistic Central Asia studies, since it has enabled historians to identify 45 different Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, while written sources only speak of 10. The coins struck by the Greek kings are often remarkable, both because of their quality and the multiple innovations some of them show: Indian iconography, local language (Brahmi or Kharoshthi), new weight system, etc. Yet, broad studies by properly trained numismatists still remained scarce, while new coins mainly find their origin on the art market rather than archaeological digs. The current situation in Central Asia, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, does not help archaeologists to broaden their fieldwork. Die-studies are more and more often the methodology followed by the numismatists in the last decade, so as to draw as much data as possible from large corpora. During our PhD research, we focused on six kings: Diodotus I and II, Euthydemus I, Eucratides I, Menander I and Hippostratus. Beyond individual results and hypothesis, we tried to ascertain this particular methodology regarding Central Asia Greek coinages. Generally, our die-studies provided good outcomes, while most of our attempts to geographically locate mints or even borders remain quite fragile, in the lack of archaeological data. -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

THE HELLENISTIC RULERS and THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* I the Beginning of the Reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II I

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ancient society 29.1998-99 (1998), S. 147-174 THE HELLENISTIC RULERS AND THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* i The beginning of the reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II in the year 145 bc following the death of his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor was described in a very negative way by ancient authors1. According to Athenaeus Ptolemy who ruled over Egypt... received from the Alexandrians appropriately the name of Malefactor. For he murdered many of the Alexandrians; not a few he sent into exile, and filled the islands and towns with men who had grown up with his brother — philologians, philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, painters, athletic trainers, physicians, and many other men of skill in their profession2. It is true that anecdotal tradition, as we find it here, is mostly of tenden tious origin, «but the course of the events suggests that the gossip-mon- * This article is the expanded version of a paper given on 2 November 1995, at the University of St Andrews, and — in a slightly changed version — on 3 November 1995, during the «Leeds Latin Seminar* on «Epigrams and Politics*. I would like to thank my colleagues there very much, especially Michael Whitby (now Warwick), for their invita tion, their hospitality, and stimulating discussions. Moreover, I would like to thank Jurgen Malitz (Eichstatt), Doris Meyer and Eckhard Wirbelauer (both Freiburg/Brsg.) for numer ous suggestions, Joachim Mathieu (Eichstatt/Atlanta) for the translation, and Roland G. Mayer (London) for his support in preparing the paper. 1 For biographical details cf. H. V olkmann , art. Ptolemaios VIII. -

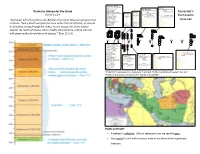

Alexander's Successors

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander