As Alexander Says. the Alexander-Dream Motif in Plutarch's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

(1988) 116–118 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt Gmbh, Bonn

E. BADIAN TWO POSTSCRIPTS ON THE MARRIAGE OF PHILA AND BALACRUS aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 73 (1988) 116–118 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 116 TWO POSTSCRIPTS ON THE MARRIAGE OF PHILA AND BALACRUS Waldemar Heckel (ZPE 70,1987,161-2) has done a service to prosopography of Alexander and the Diadochoi by his acute demonstration that the marriage of Phila and Balacrus, Alexander's satrap of Cilicia, must be accepted as historical fact. In view of the inadequacy of our source for the connection (the writer of romance, Antonius Diogenes, as recorded by Photius), it had been inconclusively discussed ever since Droysen first accepted it and then changed his mind about it.1) The dedication by an Antipater son of "Balagros" indeed establishes the fact. There is perhaps slight further confirmation for the identification discovered by Heckel in the spelling of "Balagros": the inscription coincides with Photius in this detail, and the spelling is a very rare variant.2) a.) Heckel should not, however, be followed in his acceptance of the authenticity of the letter cited by the Greek novelist. His statement that Photius "preserves, on the testimony of Antonius Diogenes, the details of a letter ..." is followed by his use of the letter in order to show that Phila cannot have been with her husband when he cook over the satrapy of Cilicia, since he still wrote to her from Tyre. In fact, there cannot be any doubt that the letter is fictitious: it pro- vides the setting for Diogenes' romance and the details are historically worthless. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note : Geographical landmarks are listed under the proper name itself: for “Cape Sepias” or “Mt. Athos” see “Sepias” or “Athos.” When a people and a toponym share the same base, see under the toponym: for “Thessalians” see “Thessaly.” Romans are listed according to the nomen, i.e. C. Julius Caesar. With places or people mentioned once only, discretion has been used. Abdera 278 Aeaces II 110, 147 Abydus 222, 231 A egae 272–273 Acanthus 85, 207–208, 246 Aegina 101, 152, 157–158, 187–189, Acarnania 15, 189, 202, 204, 206, 251, 191, 200 347, 391, 393 Aegium 377, 389 Achaia 43, 54, 64 ; Peloponnesian Aegospotami 7, 220, 224, 228 Achaia, Achaian League 9–10, 12–13, Aemilius Paullus, L. 399, 404 54–56, 63, 70, 90, 250, 265, 283, 371, Aeolis 16–17, 55, 63, 145, 233 375–380, 388–390, 393, 397–399, 404, Aeschines 281, 285, 288 410 ; Phthiotic Achaia 16, 54, 279, Aeschylus 156, 163, 179 286 Aetoli Erxadieis 98–101 Achaian War 410 Aetolia, Aetolian League 12, 15, 70, Achaius 382–383, 385, 401 204, 250, 325, 329, 342, 347–348, Acilius Glabrio, M. 402 376, 378–380, 387, 390–391, 393, Acragas 119, COPYRIGHTED165, 259–261, 263, 266, 39MATERIAL6–397, 401–404 352–354, 358–359 Agariste 113, 117 Acrocorinth 377, 388–389 Agathocles (Lysimachus ’ son) 343, 345 ; Acrotatus 352, 355 (King of Sicily) 352–355, 358–359; Actium 410, 425 (King of Bactria) 413–414 Ada 297 Agelaus 391, 410 A History of Greece: 1300 to 30 BC, First Edition. Victor Parker. -

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions Inaugural Colloquium of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network (HCARN) Department of Classics, University of Reading (UK) 15-17 April 2016 ABSTRACTS All conference sessions will be held in Lecture Room G 15, Henley Business School, University of Reading Whiteknights Campus. Baralay, Supratik (University of Oxford) The Arsakids between the Seleucids and the Achaemenids Abstract pending. Bordeaux, Olivier (Paris-Sorbonne) Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics: Methodologies, new research and limits Numismatics is one of the leading fields in Hellenistic Central Asia studies, since it has enabled historians to identify 45 different Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, while written sources only speak of 10. The coins struck by the Greek kings are often remarkable, both because of their quality and the multiple innovations some of them show: Indian iconography, local language (Brahmi or Kharoshthi), new weight system, etc. Yet, broad studies by properly trained numismatists still remained scarce, while new coins mainly find their origin on the art market rather than archaeological digs. The current situation in Central Asia, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, does not help archaeologists to broaden their fieldwork. Die-studies are more and more often the methodology followed by the numismatists in the last decade, so as to draw as much data as possible from large corpora. During our PhD research, we focused on six kings: Diodotus I and II, Euthydemus I, Eucratides I, Menander I and Hippostratus. Beyond individual results and hypothesis, we tried to ascertain this particular methodology regarding Central Asia Greek coinages. Generally, our die-studies provided good outcomes, while most of our attempts to geographically locate mints or even borders remain quite fragile, in the lack of archaeological data. -

The Making of the Hellenistic World

Part I THE MAKING OF THE HELLENISTIC WORLD K2 cch01.inddh01.indd 1111 99/14/2007/14/2007 55:03:23:03:23 PPMM K2 cch01.inddh01.indd 1122 99/14/2007/14/2007 55:03:23:03:23 PPMM 1 First Steps 325 300 275 250 225 200 175 150 125 100 75 50 25 June 323 Death of Alexander the Great; outbreak of Lamian War 322 Battle of Krannon; end of Lamian War 320 Death of Perdikkas in Egypt; settlement of Triparadeisos 319 Death of Antipater 317 Return of Olympias to Macedonia; deaths of Philip Arrhidaios and Eurydike 316/15 Death of Eumenes of Kardia in Iran 314 Antigonos’ declaration of Tyre; fi rst coalition war (Kas- sander, Lysimachos, and Ptolemy against Antigonos) 312 Battle of Gaza; Seleukos retakes Babylon 311 Treaty ends coalition war 310 Deaths of Alexander IV and Roxane I From Babylon to Triparadeisos The sudden death of the Macedonian king Alexander, far away from home at Babylon in Mesopotamia on June 10, 323, caught the world he ruled fully unprepared for the ensuing crisis. Only two of the men who founded the dynas- ties of kings which dominated the history of the Hellenistic world were even present at Babylon when he died, and only one of them was suffi ciently promi- nent among the offi cers who assembled to debate the future to be given an independent provincial command: Ptolemy, now in his early forties, was appointed to distant Egypt (though with Alexander’s established governor, Kleomenes, as his offi cial deputy). Seleukos, also present at Babylon, but some K2 cch01.inddh01.indd 1133 99/14/2007/14/2007 55:03:23:03:23 PPMM 14 PART I THE MAKING OF THE HELLENISTIC WORLD ten years younger, became cavalry commander in the central government, a post which under Alexander had been equivalent to the king’s deputy but now was envisaged as being purely military. -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

THE HELLENISTIC RULERS and THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* I the Beginning of the Reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II I

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ancient society 29.1998-99 (1998), S. 147-174 THE HELLENISTIC RULERS AND THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* i The beginning of the reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II in the year 145 bc following the death of his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor was described in a very negative way by ancient authors1. According to Athenaeus Ptolemy who ruled over Egypt... received from the Alexandrians appropriately the name of Malefactor. For he murdered many of the Alexandrians; not a few he sent into exile, and filled the islands and towns with men who had grown up with his brother — philologians, philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, painters, athletic trainers, physicians, and many other men of skill in their profession2. It is true that anecdotal tradition, as we find it here, is mostly of tenden tious origin, «but the course of the events suggests that the gossip-mon- * This article is the expanded version of a paper given on 2 November 1995, at the University of St Andrews, and — in a slightly changed version — on 3 November 1995, during the «Leeds Latin Seminar* on «Epigrams and Politics*. I would like to thank my colleagues there very much, especially Michael Whitby (now Warwick), for their invita tion, their hospitality, and stimulating discussions. Moreover, I would like to thank Jurgen Malitz (Eichstatt), Doris Meyer and Eckhard Wirbelauer (both Freiburg/Brsg.) for numer ous suggestions, Joachim Mathieu (Eichstatt/Atlanta) for the translation, and Roland G. Mayer (London) for his support in preparing the paper. 1 For biographical details cf. H. V olkmann , art. Ptolemaios VIII. -

Alexander's Successors

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander -

Eumenes by Plutarch

Eumenes By Plutarch (legendary, reigned 197 B.C.E. - ca. 160 B.C.E.) Translated by John Dryden Duris reports that Eumenes, the Cardian, was the son of a poor wagoner in the Thracian Chersonesus, yet liberally educated, both as a scholar and a soldier; and that while he was but young, Philip, passing through Cardia, diverted himself with a sight of the wrestling matches and other exercises of the youth of that place, among whom Eumenes performing with success, and showing signs of intelligence and bravery, Philip was so pleased with him as to take him into his service. But they seem to speak more probably who tell us that Philip advanced Eumenes for the friendship he bore to his father, whose guest he had sometime been. After the death of Philip, he continued in the service of Alexander, with the title of his principal secretary, but in as great favour as the most intimate of his familiars, being esteemed as wise and faithful as any person about him, so that he went with troops under his immediate command as general in the expedition against India, and succeeded to the post of Perdiccas, when Perdiccas was advanced to that of Hephaestion, then newly deceased. And therefore, after the death of Alexander, when Neoptolemus, who had been captain of his life-guard, said that he had followed Alexander with shield and spear, but Eumenes only with pen and paper, the Macedonians laughed at him, as knowing very well that, besides other marks of favour, the king had done him the honour to make him a kind of kinsman to himself by marriage. -

Eumenes of Cardia Mnemosyne Supplements History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity

Eumenes of Cardia Mnemosyne Supplements history and archaeology of classical antiquity Series Editor Hans van Wees (University College London) Associate Editors Jan Paul Crielaard (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) Benet Salway (University College London) VOLUME 383 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mns-haca Eumenes of Cardia A Greek among Macedonians By Edward M. Anson LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Left coin: silver tetradrachm depicting Ptolemy I Soter, issued by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC); right coin: silver tetradrachm depicting Zeus, issued in the reign of Philip II, King of Macedonia (359–336 BC). Courtesy of the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anson, Edward. Eumenes of Cardia : a Greek among Macedonians / by Edward M. Anson. — Second edition. pages cm — (Mnemosyne Supplements, History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity, ISSN 2352-8656 ; volume 383) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-90-04-29715-9 (hardback : alk. paper) — isbn 978-90-04-29717-3 (e-book) 1. Eumenes, of Cardia, 362 B.C. or 361 B.C.–316 B.C. or 315 B.C. 2. Greece—History—Macedonian Hegemony, 323–281 B.C. 3. Macedonia—History—Diadochi, 323-276 B.C. 4. Generals—Greece—Biography. i. Title. DF235.48.E96A57 2015 938’.07092—dc23 [B] 2015017742 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. The first edition of this title was published as volume 3 in the Brill series Studies in Philo of Alexandria, under ISBN 978-03-91-04209-4. -

1 Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia

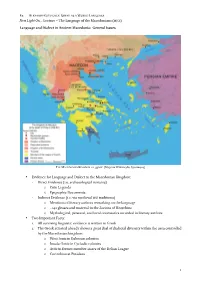

E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia: General Issues THE MACEDONIAN KINGDOM CA. 336 BC (Map via Wikimedia Commons) • Evidence for Language and Dialect in the Macedonian Kingdom: - Direct Evidence (i.e. archaeological remains) o Coin Legends o Epigraphic Documents - Indirect Evidence (i.e. via medieval MSS traditions) o Mentions of literary authors remarking on the language o ~140 glosses and material in the Lexicon of Hesychius o Mythological, personal, and local onomastics recorded in literary authors • Two Important Facts: 1. All surviving linguistic evidence is written in Greek 2. The Greek attested already shows a great deal of dialectal diversity within the area controlled by the Macedonian kingdom: o West Ionic in Euboean colonies o Insular Ionic in Cycladic colonies o Attic in former member states of the Delian League o Corinthian at Potidaea 1 E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) o Attic-Ionic koiné in Macedonian official inscriptions Regarding the ‘Greekness’ of the Macedonians and their Language(s) • Evidence from literary sources is divided on the original ethnic and linguistic identity of the Ancient Macedonians: o Hesiod fr. 7: Eponymous ancestor Μακεδών born to Zeus and one of Deucalion’s daughters. o Herodotus (5.22, 8.137-139) strongly states a belief that Macedonians were Greeks o Thucydides (2.80.5-7, 2.81.6, 4.124.1) possibly considers Macedonians to be βάρβαροι. o Aristotle (1324b) includes Macedonians in a list of ἔθνη with despotic practices (ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσι πᾶσι τοῖς δυναµένοις πλεονεκτεῖν), but makes no reference to language. -

JOHN WALSH, Antipater and Early Hellenistic Literature

Antipater and Early Hellenistic Literature* John Walsh INTRODUCTION It is well known that there was a flowering of Greek literature under Alexander and in the period after his death – at least in terms of the quantity of works, even if some may dispute the quality. A vast array of histories, memoirs, pamphlets, geographical literature, philosophical treatises, and poetry was written during this period, and the political fate of the Greek world in its domination by Macedon and the Successor kingdoms was tied to an increasing tendency for kings to be patrons of literature. Many works were now produced at royal courts, under the patronage of the Successors or by partisan individuals who had served under various kings.1 Antipater, Alexander’s regent in Macedonia, has a neglected but interesting connection with literature in the early Hellenistic era. Antipater was certainly overshadowed by both Philip and Alexander, and the other Diadochs, and his place in the development of Hellenistic intellectualism and literature has been overlooked in modern scholarship. First, in Sections I and II below, I show that Antipater, as Philip had done before him, had a role in the development of Hellenistic literature and was himself an author. There were also intriguing, if speculative, connections between Antipater’s court and the emerging tradition of historical epic. Secondly, in Section III, I trace how Antipater suffered unduly from hostile historiographical traditions directed at him by the propaganda of rival Diadochs, particularly those produced under Ptolemy and the Antigonid partisan Hieronymus of Cardia. I. ANTIPATER’S WORKS2 A passage in the Suda provides some tantalising evidence of Antipater as a writer of history and letters: Antipater was the son of Iolaus, of the city Paliura in Macedonia.