Realized Volatility and Variance: Options Via Swaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

Arithmetic Variance Swaps

Arithmetic variance swaps Article (Accepted Version) Leontsinis, Stamatis and Alexander, Carol (2017) Arithmetic variance swaps. Quantitative Finance, 17 (4). pp. 551-569. ISSN 1469-7688 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/62303/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Arithmetic Variance Swaps Stamatis Leontsinisa and Carol Alexanderb a RwC Asset Management, London b School of Business, Management and Economics, University of Sussex To appear in Quantitative Finance, 2016 (in press) Abstract Biases in standard variance swap rates can induce substantial deviations below market rates. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

Pricing Financial Derivatives Under the Regime-Switching Models Mengzhe Zhang

Pricing Financial Derivatives Under the Regime-Switching Models Mengzhe Zhang A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Mathematics and Statistics Faculty of Science, University of New South of Wales, Australia 19th April 2017 Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Leung Lung Chan for his valuable guidance, helpful comments and enlightening advice throughout the preparation of this thesis. I also want to thank my parents for their love, support and encouragement throughout my graduate study time at the University of NSW. Last but not the least, I would like to thank my friends- Dr Xin Gao, Dr Xin Zhang, Dr Wanchuang Zhu, Dr Philip Chen and Dr Jinghao Huang from the Math school of UNSW and Dr Zhuo Chen, Dr Xueting Zhang, Dr Tyler Kwong, Dr Henry Rui, Mr Tianyu Cai, Mr Zhongyuan Liu, Mr Yue Peng and Mr Huaizhou Li from the Business school of UNSW. i Contents 1 Introduction1 1.1 BS-Type Model with Regime-Switching.................5 1.2 Heston's Model with Regime-Switching.................6 2 Asymptotics for Option Prices with Regime-Switching Model: Short- Time and Large-Time9 2.1 Introduction................................9 2.2 BS Model with Regime-Switching.................... 13 2.3 Small Time Asymptotics for Option Prices............... 13 2.3.1 Out-of-the-Money and In-the-Money.............. 13 2.3.2 At-the-Money........................... 25 2.3.3 Numerical Results........................ 35 2.4 Large-Maturity Asymptotics for Option Prices............. 39 ii 2.5 Calibration................................ 53 2.6 Conclusion................................. 57 3 Saddlepoint Approximations to Option Price in A Regime-Switching Model 59 3.1 Introduction............................... -

Further Developments in Volatility Derivatives Modeling

Introduction Prior work Parameter estimation Model vs market prices Conclusion Further Developments in Volatility Derivatives Modeling Jim Gatheral Global Derivatives Trading & Risk Management, Paris May 21, 2008 Introduction Prior work Parameter estimation Model vs market prices Conclusion Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of of Merrill Lynch, its subsidiaries or affiliates. Introduction Prior work Parameter estimation Model vs market prices Conclusion Motivation and context We would like to have a model that prices consistently 1 options on SPX 2 options on VIX 3 options on realized variance We believe there may be such a model because we can identify relationships between options on SPX, VIX and variance. For example: 1 Puts on SPX and calls on VIX both protect against market dislocations. 2 Bruno Dupire constructs an upper bound on the price of options on variance from the prices of index options. 3 The underlying of VIX options is the square-root of a forward-starting variance swap. The aim is not necessarily to find new relationships; the aim is to devise a tool for efficient determination of relative value. Introduction Prior work Parameter estimation Model vs market prices Conclusion Outline 1 Review of prior work Double Lognormal vs Double Heston 2 Parameter estimation Time series analysis of variance curves Time series analysis of SABR fits to SPX options 3 Model vs market prices Numerical techniques Pricing of options on VIX and SPX Options on realized variance 4 Conclusion Is the model right? Introduction Prior work Parameter estimation Model vs market prices Conclusion Review of prior work We found that double-mean reverting lognormal dynamics for SPX instantaneous variance gave reasonable fits to both SPX and VIX option volatility smiles. -

Credit Derivatives Handbook

08 February 2007 Fixed Income Research http://www.credit-suisse.com/researchandanalytics Credit Derivatives Handbook Credit Strategy Contributors Ira Jersey +1 212 325 4674 [email protected] Alex Makedon +1 212 538 8340 [email protected] David Lee +1 212 325 6693 [email protected] This is the second edition of our Credit Derivatives Handbook. With the continuous growth of the derivatives market and new participants entering daily, the Handbook has become one of our most requested publications. Our goal is to make this publication as useful and as user friendly as possible, with information to analyze instruments and unique situations arising from market action. Since we first published the Handbook, new innovations have been developed in the credit derivatives market that have gone hand in hand with its exponential growth. New information included in this edition includes CDS Orphaning, Cash Settlement of Single-Name CDS, Variance Swaps, and more. We have broken the information into several convenient sections entitled "Credit Default Swap Products and Evaluation”, “Credit Default Swaptions and Instruments with Optionality”, “Capital Structure Arbitrage”, and “Structure Products: Baskets and Index Tranches.” We hope this publication is useful for those with various levels of experience ranging from novices to long-time practitioners, and we welcome feedback on any topics of interest. FOR IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION relating to analyst certification, the Firm’s rating system, and potential conflicts -

White Paper Volatility: Instruments and Strategies

White Paper Volatility: Instruments and Strategies Clemens H. Glaffig Panathea Capital Partners GmbH & Co. KG, Freiburg, Germany July 30, 2019 This paper is for informational purposes only and is not intended to constitute an offer, advice, or recommendation in any way. Panathea assumes no responsibility for the content or completeness of the information contained in this document. Table of Contents 0. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Ihe VIX Index .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 General Comments and Performance ......................................................................................... 2 What Does it mean to have a VIX of 20% .......................................................................... 2 A nerdy side note ................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 The Calculation of the VIX Index ............................................................................................. 4 1.3 Mathematical formalism: How to derive the VIX valuation formula ...................................... 5 1.4 VIX Futures .............................................................................................................................. 6 The Pricing of VIX Futures ................................................................................................ -

Volatility As Investment - Crash Protection with Calendar Spreads of Variance Swaps

Journal of Applied Operational Research (2014) 6(4), 243–254 © Tadbir Operational Research Group Ltd. All rights reserved. www.tadbir.ca ISSN 1735-8523 (Print), ISSN 1927-0089 (Online) Volatility as investment - crash protection with calendar spreads of variance swaps Uwe Wystup 1,* and Qixiang Zhou 2 1 MathFinance AG, Frankfurt, Germany 2 Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Germany Abstract. Nowadays, volatility is not only a risk measure but can be also considered an individual asset class. Variance swaps, one of the main investment vehicles, can obtain pure exposure on realized volatility. In normal market phases, implied volatility is often higher than the realized volatility will turn out to be. We present a volatility investment strategy that can benefit from both negative risk premium and correlation of variance swaps to the underlying stock index. The empirical evidence demonstrates a significant diversification effect during the financial crisis by adding this strategy to an existing portfolio consisting of 70% stocks and 30% bonds. The back-testing analysis includes the last ten years of history of the S&P500 and the EUROSTOXX50. Keywords: volatility; investment strategy; stock index; crash protection; variance swap * Received July 2014. Accepted November 2014 Introduction Volatility is an important variable of the financial market. The accurate measurement of volatility is important not only for investment but also as an integral part of risk management. Generally, there are two methods used to assess volatility: The first one entails the application of time series methods in order to make statistical conclusions based on historical data. Examples of this method are ARCH/GARCH models. -

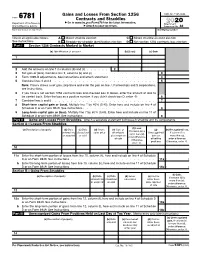

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949.