The Guattari Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Sociological Investigation of the Conceptions and Perceptions of Mental Health and Illness in Arica, Chile and Rome, Italy

A Comparative Sociological Investigation of the Conceptions and Perceptions of Mental Health and Illness in Arica, Chile and Rome, Italy Researcher: Nelly-Ange Kontchou B.A. Candidate in Combined Spanish & Italian Studies, Duke University Advisors: Dr. Luciana Fellin & Professor Richard Rosa Abstract This comparative study aimed to discover the principal factors that influence the perceptions of citizens in Arica, Chile and Rome, Italy toward mental illness. Specifically, the study aimed to investigate how these perceptions affect the societal acceptance of mentally ill individuals and to identify potential sources of stigma. In both cities, mental health services exist for free use by citizens, but stigma makes the use of these services and the acceptance of those who use them somewhat taboo. Past studies on the topic of mental health stigma have investigated the barriers to accessing mental health services (Acuña & Bolis 2005), the inception and effects of Basaglia’s Law (Tarabochia 2011), strategies to combat stigma (López et al. 2008) and images of mental illness in the media (Stout, Villeagas & Jennings 2004). To discover Aricans’ opinions on mental health and illness, personal interviews were administered to five mental health professionals, and a 20-question survey was administered to 131 members of the general population. In Rome, 27 subjects answered an 18-question survey as well as an interview, and 12 professionals participated in narrative interviews. From these interviews and surveys, the lack of economic, structural and human resources to effectively manage mental health programs was gleaned. Moreover, many participants identified how stigma infringed upon the human rights of those with mental illnesses and opined that they were barely accepted in society. -

Antipsychiatry Movement 29 Wikipedia Articles

Antipsychiatry Movement 29 Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 29 Aug 2011 00:23:04 UTC Contents Articles Anti-psychiatry 1 History of anti-psychiatry 11 Involuntary commitment 19 Involuntary treatment 30 Against Therapy 33 Dialectics of Liberation 34 Hearing Voices Movement 34 Icarus Project 45 Liberation by Oppression: A Comparative Study of Slavery and Psychiatry 47 MindFreedom International 47 Positive Disintegration 50 Radical Psychology Network 60 Rosenhan experiment 61 World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry 65 Loren Mosher 68 R. D. Laing 71 Thomas Szasz 77 Madness and Civilization 86 Psychiatric consumer/survivor/ex-patient movement 88 Mad Pride 96 Ted Chabasinski 98 Lyn Duff 102 Clifford Whittingham Beers 105 Social hygiene movement 106 Elizabeth Packard 107 Judi Chamberlin 110 Kate Millett 115 Leonard Roy Frank 118 Linda Andre 119 References Article Sources and Contributors 121 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 124 Anti-psychiatry 1 Anti-psychiatry Anti-psychiatry is a configuration of groups and theoretical constructs that emerged in the 1960s, and questioned the fundamental assumptions and practices of psychiatry, such as its claim that it achieves universal, scientific objectivity. Its igniting influences were Michel Foucault, R.D. Laing, Thomas Szasz and, in Italy, Franco Basaglia. The term was first used by the psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967.[1] Two central contentions -

Marriages of Portsmouth Virginia 1858-1901 a - F Date Husband Wife Ages Status Birthplace Currently Living @ Parents Husband Wife Husband Wife

Marriages of Portsmouth Virginia 1858-1901 A - F Date Husband Wife Ages Status Birthplace Currently living @ Parents Husband Wife Husband Wife ABBOTT Richard P & Joseph KNIGHT South Mills Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth B M & Lovey Ann Eliza 26 Jan 1888 Wilson Hattie Noel 22 18 S S NC VA VA VA V Abbott Knight Morris & ABRAHAM ROBINSON Portsmouth Sarah Max & Mary 26 Jun 1900 Pyser Rebecca 23 19 S W NY NY Edenton NC VA Abraham Reshefsky NICHOLSON William and ACH James Fannie Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth James and Kate 30 Dec 1890 Henry Franklin 27 25 S S VA VA VA VA Mary R Ash Nicholson John P & Lorin W & ACKERLY Rockbridge Portsmouth Portsmouth Mary Jane Martha C 28 Aug 1866 Holcomb S LANE Lucy R 22 18 S S Co VA VA Savanah GA VA Ackerly Lane William D & ACKLAND HANSON Cristine Dinwiddie Co Portsmouth Portsmouth Israel & Beta Louisa 30 Sep 1886 Charles John Elizabeth 39 42 W W Finland VA VA VA Acklund Ebinnather George F & William & ADAMS WAGGNER Fredericksbu Baltimore Portsmouth Portsmouth Mary Ann Mary 10 Oct 1860 Charles B Elizabeth A 27 24 S S rg VA MD VA VA Davis Waggner ADAMS WHITEHUR King and John H & D W & Charles ST Permelia Queen Co Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth Maria L Permelia O 23 Nov 1892 Everett Owens 26 24 S S VA VA VA VA Adams Whitehurst John A & Richard & ADAMS VAN PELT Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth Portsmouth Sarah Caroline 4 Aug 1879 George H Vienna 28 22 S S VA VA VA VA Adams VanPelt ADAMS King & John H & Oscar D & Logan BATES Alice Queen Co Baltimore Portsmouth Portsmouth Maria C Maggie C 18 Oct -

Metaphors in Madness Narratives

humanities Article A Mind Trying to Right/Write Itself: Metaphors in Madness Narratives Renana Stanger Elran Independent Researcher, Modiin 7172420, Israel; [email protected] Received: 20 February 2019; Accepted: 19 June 2019; Published: 25 June 2019 Abstract: This article explores autobiographical madness narratives written by people with lived experience of psychosis, dated from the mid-19th century until the 1970s. The focus of the exploration is on the metaphors used in these narratives in order to communicate how the writers experienced and understood madness from within. Different metaphors of madness, such as going out of one’s mind, madness as an inner beast, another world, or a transformative journey are presented based on several autobiographical books. It is argued that these metaphors often represent madness as the negative picture of what it is to be human, while the narrative writing itself helps to restore a sense of belonging and personhood. The value and function of metaphors in illness and madness narratives is further discussed. Keywords: psychosis; madness; schizophrenia; narrative; autobiography; metaphor; history of 1. Introduction Madness challenges the mainstream way of being a person in the world; going out of one’s mind is also going out of the matrix of normative thoughts, emotions, and actions. A person going through a psychotic episode (psychosis being the archetypal representation of madness) is deeply convinced by the subjective experience of reality, though it seems unlikely or even bizarre and differs from what is understood by others to be real. When psychotic experiences are looked upon in retrospect, the story of the self in times of madness can seem to the person themselves as deeply intimate but also as strange and alien, both profound and meaningless at the same time. -

The Cultural Repertoire of Franco Basaglia and the Comparative Critique of Psychiatry

ORIGINAL PAPER THE CULTURAL REPERTOIRE OF FRANCO BASAGLIA AND THE COMPARATIVE CRITIQUE OF PSYCHIATRY Giovanni Matera, PhD1 ISSN: 2283-8961 Abstract Can we consider Franco Basaglia as “the man who closed the asylums” or would it be more appropriate to refer to him as the spokesperson of a large group of professionals and instances? My thesis underlines the collective work carried out by a group of psychiatric professionals in the 1960s and the 1970s. Their acknowledgement of experiences drawing from different cultural repertoires allowed them to transform psychiatric services into a democratic institution. The paper develops through three sections which help us to understand the connection between the work of Basaglia and other western countries, especially France. 1) The circulation of knowledge among western countries has contributed to the production of “cultural repertoires of evaluation” available in all these western countries in an uneven way but based on a common sense of injustice. 2) Drawing from the work of sociologist Robert Castel, I will examine the relation between the group of Basaglia and the “secteur” model, available in France since the end of the Second World War. 3) I will eventually analyze some 1 Sociologist, associate member at Centre Georg Simmel – EHESS [email protected] Rivista di Psichiatria e Psicoterapia Culturale, Vol. VIII, n. 2, Novembre 2020 The cultural repertoire of Franco Basaglia 2 G Matera interviews released in the 1970s in which Franco Basaglia and his colleagues discuss the connection between their experiments and the ones conducted in other western countries. Key words: Community Psychiatry, Franco Basaglia, Pragmatic Sociology, Cultural Sociology, Cultural Repertoires of Evaluation. -

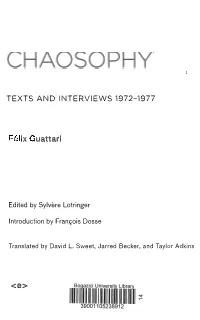

TEXTS and INTERVIEWS 1972-1977 Ix Uattari Edited By

TEXTS AND INTERVIEWS 1972-1977 ix uattari Edited by Sylvere Lotringer Introduction by FranQois Dosse Translated by David L. Sweet, Jarred Becker, and Taylor Adkins <e> SEMIOTEXT(E) FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES Copyright © 2009 Felix Guattari and Semiotext(e) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Published by Semiotext(e) 2007 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 427, Los Angeles, CA 90057 www.semiotexte.com Special thanks to Robert Dewhurst, Emmanuelle Guattari, Benjamin Meyers, Frorence Petri, and Danielle Sivadon. The Index was prepared by Andrew Lopez. Cover Art by Pauline Stella Sanchez. Gone Mad Blue/Color Vaccine Architecture or 3 state sculpture:before the event, dur ing the event, and after the event, #4. (Seen here during the event stage.) 2004. Te mperature, cartoon colour, neo-plastic memories, glue, dominant cinema notes, colour balls, wood, resin, meta-allegory of architecture as body. 9 x 29 1/4 x 18" Design by Hedi El Kholti ISBN: 978-1-58435-060-6 Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England Printed in the United States of America ontents Introduction by Franc;ois Dosse 7 PART I: DELEUZEIGUATTARI ON ANTI-OEDIPUS 1. Capitalism: A Very Special Delirium 35 f 2. Capitalism and Schizophrenia 53 3. In Flux 69 4. Balance-Sheet for "Desiring-Machines" 90 PART II: BEYOND AN ALYSIS 5. Guerrilla in Psychiatry: Franco Basaglia 119 6. Laing Divided 124 7. Mary Barnes's "Trip" 129 8. -

Psychiatric Hospital of Gorizia

Assembling memories and affective practices around the psychiatric history of Gorizia: A study of a remembering crisis Ph.D. Thesis Elena Trivelli Ph.D. Candidate Department of Media and Communications Goldsmiths University University of London I declare that this thesis is my own work, based on my personal research, and that I have acknowledged all material and sources used in its preparation. I also declare that this thesis has not previously been submitted for assessment in any other unit, and that I have not copied in part or whole or otherwise plagiarised the work of others. Signature Date 2 THESIS ABSTRACT This thesis examines the vicissitudes around psychiatric practice in the Italian city of Gorizia, from the 1960s to the present day. It addresses the work of alternative psychiatry initiated by Franco Basaglia in the city, in the early 1960s, and how this work has been remembered in the local community across the decades. It is an interdisciplinary qualitative case study research based on an ethnography I conducted in Gorizia between 2011 and 2012, which has primarily involved archival research, formal interviews and informal conversations with some of the protagonists of psychiatric deinstitutionalisation in the city. I analyse how elements such as narratives around ‘Basaglia in Gorizia’, public events and health care approaches, as well as the state of several locales and resources in official archives, are informed by fractured and contrasting understandings of the meaning of ‘the Basaglia experience’, and I frame such cleavages in terms of a ‘remembering crisis’. Within the scarcity of historical research that has been conducted on the psychiatric history of Gorizia, I suggest that these cleavages are crucial for an analysis of the cyclical erasures, rewritings and forms of ‘removal’ that are structural features in remembering ‘the Basaglia experience’ in the city. -

"Flection" and "Reflection"

Flection . BY MARY BARNES FLECTION: the act of bending or the state of being bent. That's how I was at Kingsley Hall, bent back into a womb of rebirth. From this cocoon I emerged, changed to the self I had almost lost. TIle buried me, entangled in guilt and choked with anger as a plant matted in weed, grew anew, freed from the knots of my past. That was Kingsley Hall to me, a backward somer sault, a breakdown, a purification, a renewal. It was a place of rest, of utter stillness, of terrible turmoil, of the most shattering violence, of panic and of peace, of safety and security and of risk and reckless joy. It was the essence of life. The world, caught, held, contained, in space and time. Five years as five seconds; five seconds as five hundred years. Kingsley Hall, my 'second' life, my 'second' family, may it ever live within me. My life, within a life. It was a seed, a kernel of the time to come. How can I know what will come. As I write, as I paint, the words, the colours-they emerge, grow, take shape, blend, and part; a sharp line, darkness; light. The 288 Mary Barnes Flection 289 canvas, a paper, a life, is full, complete, whole. We distractions; cut off from Cod; division of the self; are at one with Cod. Through the half light, the 'to die to the self to live in Cod'; to get free from the blessed blur of life, we stumble to the Cod we sense self in the mother to live in God within the self; 'our within. -

Antipsychiatry As the Stigma

Psychiatria Danubina, 2017; Vol. 29, Suppl. 5, pp S890-894 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia ANTIPSYCHIATRY AS THE STIGMA Izet Pajević & Mevludin Hasanović Department of Psychiatry University Clinical Center Tuzla, School of Medicine University of Tuzla, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina SUMMARY The authors presents their perspectives on the relationship between antipsychiatry and the stigma of mental illness. The present paper aims to provide a short review of the basic principles of the antipsychiatric movement, and to discuss the atitudes of its most important theorists. The authors searched recent literature, as well as drawing upon some of the basic antipsychiatric texts. Antipsychiatry dates from 18th century, and as an international movement it emerged during the 1960s as part of the historic tumult of the period rather than as a result of the evolution of scientific ideas. During that period psychiatrists began to see heredity as the cause of mental illness, became pessimistic about restoring patients to sanity, and adopted essentially a custodial approach to care that included use of physical restraints. Radical attitudes of antipsychiatry gave a significant incentive to review psychiatric theory and practice, especially with protecting the rights of mental patients and giving importance not only to somatic, but mental, social and spiritual sides of human existence. But, at the same time, they led to unwarranted attacks on psychiatry as a medical discipline, encouraged different views of its stigmatization and in a certain measure affected the weakening of social awareness about the importance of medical and institutional care for the mentally ill persons. After the 1970s, the antipsychiatry movement became increasingly less influential, due in particular to the rejection of its politicized and reductionistic understanding of psychiatry. -

From Basaglia to Brazil

MAD MARGINAL Cahier #1 FRoM BAsaglia to BRAzIL A book by Dora García Published by Mousse Published by Mousse 1 WoRkING toGetheR BetWeeN As part of the Trentoship and Trento.link projects, Dora García’s workshop at Fondazione Galleria Civica di Trento is MADNess AND MARGINALIty one step in a symbolic path, one which has led the museum to examine an elsewhere and an other that can be found, moreover, at the threshold of the museum itself: by investigating the “public dimension”, the intimately “social” role - open-ended, interactive and narrative - of the contemporary cultural institution, Dora García presents the institution with a snapshot of itself, in all of its idiosyncrasies, contradictions, and inhibitions, comparing its hypothetical agenda to its real, day-to-day priorities, revealing its aspect of pure potentiality, showing how it hovers between a chronicle of action and a (vital) need to constantly reinvent itself. Dora García’s work is structured around unconventional formats of a conceptual nature: texts, photographs, and installations, conceived for specific spaces at the institutions where she works. Often employing performance and participatory forms of art, she explores the relationship between artist, work, and viewer, presenting the various facets of a world that is, indeed, more potential than real, incorporating many layers of interpretation and experience. The workshop proposed by the artist serves as an introduction to the ongoing project “Mad Marginal”, presenting its first outgrowths (the film The Deviant Majority and this publication, Mad Marginal Cahier #1: From Basaglia to Brazil). Opening up a debate on the three main elements of the “Mad Marginal” project – radical politics, radical art, radical psychiatry - the workshop, along with this film and book, will offer an opportunity for reflecting on the many different theories and research tools that the Andrea Viliani artist employs in her work. -

Correspondence of James K. Polk

Correspondence of James K. Polk VOLUME XII, JANUARY–JULY 1847 JAMES K. POLK Hand-colored lithograph on paper by E. B. & E. C. Kellogg Lithography Company, c. 1846–47, after a daguerreotype by John Plumbe, Jr. Cropped from original size. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, New York. Correspondence of JAMES K. POLK Volume XII January–July 1847 TOM CHAFFIN MICHAEL DAVID COHEN Editors 2013 The University of Tennessee Press Knoxville Copyright © 2013 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Cloth: 1st printing, 2013. The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standards Institute / National Information Standards Organization specification Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent post- consumer waste and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (Revised) Polk, James Knox, Pres. U.S., 1795–1849. Correspondence of James K. Polk. Vol. 12 edited by T. Chaffin and M. Cohen CONTENTS: V. 1. 1817–1832.—v. 2. 1833–1834.—v. 3. 1835–1836.— v. 4. 1837–1838.—v. 5. 1839–1841.—v. 6. 1842–1843.—v. 7. 1844.— v. 8. 1844—v. 9. 1845—v. 10. 1845—v. 11. 1846.—v. 12. 1847. 1. Polk, James Knox, Pres. U.S., 1795–1849. 2. Tennessee—Politics and government—To 1865—Sources. 3. United States—Politics and government—1845–1849—Sources. 4. Presidents—United States— Correspondence. 5. Tennessee—Governors—Correspondence. I. Weaver, Herbert, ed. II. Cutler, Wayne, ed. III. Chaffin, Tom, and Michael David Cohen, eds. -

Franco Basaglia and the Radical Psychiatry Movement in Italy

Critical and Radical Social Work • vol 2 • no 2 • 235–49 • © Policy Press 2014 • #CRSW Print ISSN 2049 8608 • Online ISSN 2049 8675 • http://dx.doi.org/10.1332/204986014X14002292074708 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits adaptation, alteration, reproduction and distribution without further permission provided the original work is attributed. The derivative works do not need to be licensed on the same terms. radical pioneers Franco Basaglia and the radical psychiatry movement in Italy, 1961–78 John Foot, University of Bristol, UK [email protected] This article provides a short introduction to the life and work of Italian radical psychiatrist and mental health reformer Franco Basaglia. A leading figure in the democratic psychiatry movement, Basaglia is little known and often misunderstood in the English-speaking world. This article will seek to address this by highlighting Basaglia’s significant role in the struggle for both deinstitutionalisation and the human rights of those incarcerated in Italy’s asylums during the 1960s and 1970s. key words anti-psychiatry • deinstitutionalisation • human rights • Italy • Franco Basaglia Biography Delivered by Ingenta Copyright The Policy Press Franco Basaglia was born to a well-off family in Venice in 1924. He became an anti-fascist in his teens and was an active member of the resistance during the war in the city. In December 1944, he was arrested and spent six months inside Venice’s grim Santa Maria Maggiore prison. The liberation of the city in April 1945 saw his IP : 192.168.39.210 On: Thu, 30 Sep 2021 10:29:08 release.