GAR 2008 Journal [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Conference on Education 47Th Session

ED/MD/103 Final report International Conference on Education 47th session Geneva 8 – 11 September 2004 UNESCO International Bureau of Education (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page AGENDA ................................................................................................................................. (iii) PART I - PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE A. Opening ceremony ................................................................................................. 1 B. Organization of work – Methodology .................................................................... 2 C. Celebration of International Literacy Day ............................................................. 3 D. Closing ceremony .................................................................................................. 4 E. Award of the Comenius Medal .............................................................................. 5 F. Side-meetings.......................................................................................................... 5 PART II - DOCUMENTS ISSUED BY THE CONFERENCE A. General report ......................................................................................................... 7 B. Message from the 47th session of ICE and proposed priorities for action ........................................................................... 11 ANNEXES I. Opening address by H.E. Mr Fabian Osuji, Minister of Education of Nigeria II. Opening address by Mr Koïchiro Matsuura, Director-General of UNESCO III. Opening address by H.E. -

Xtera® Selected As the Supplier for the ARBR Subsea Cable System

1/23/2018 Xtera® Selected as the Supplier for the ARBR Subsea Cable System Xtera® Selected as the Supplier for the ARBR Subsea Cable System January 23, 2018 09:00 ET | Source: Xtera HONOLULU and ALLEN, Texas, Jan. 23, 2018 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) Xtera®, a provider of innovative subsea fibre optic solutions, today announces it has been selected as the supplier of the ARBR submarine fibre optic cable system developed jointly by Seaborn Networks and the Werthein Group. The 2,700 km open system, 4fibre pair, 48Tbps, direct PoPtoPoP subsea cable will connect Argentina and Brazil. The ARBR subsea cable system will allow for direct onward connectivity to New York, via the Seabras1 system, thereby providing a lower latency route between the commercial and financial centers of Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and New York. The ARBR cable is fully funded and on an accelerated implementation schedule to bring valuable new capacity on an underserved route, providing important new connectivity to this region. “This award further consolidates Xtera’s position as a strong player in the regional submarine market segment and is a significant endorsement of Xtera’s differentiated product offering,” says Stuart Barnes, Chairman and Chief Strategy Officer, Xtera. “Our four pillars of product and service offerings encompass subsea systems technologies, wet and dry upgrades, IP licensing, and OEM / specialist units to selected markets. Xtera is further defined by its flexible approach to system partnering and contracting structures that ensure the best value for investment and a solution aligned to each customer’s need.” The ARBR subsea cable system will utilize Xtera’s fieldproven submarine repeaters with hybrid EDFARaman design, enabling a robust optimized transmission system. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 BOARD of DIRECTORS

2016 Annual Report and Financial Statements Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Marcos Marcelo Mindlin Vice-Chairman Gustavo Mariani Director Ricardo Alejandro Torres Damián Miguel Mindlin Diego Martín Salaverri Clarisa Lifsic Santiago Alberdi Carlos Tovagliari Javier Campos Malbrán Julio Suaya de María Alternate Director José María Tenaillon Juan Francisco Gómez Mariano González Álzaga Mariano Batistella Pablo Díaz Index Alejandro Mindlin Brian Henderson Gabriel Cohen Annual Report 4 Carlos Pérez Bello Glossary of Terms 8 Gerardo Carlos Paz Consolidated Financial Statements 166 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Glossary of Terms 168 President José Daniel Abelovich Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 172 Statutory Auditor Jorge Roberto Pardo Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income (Loss) 174 Germán Wetzler Malbrán Consolidated Statement of Changes In Equity 176 Alternate Statutory Auditor Marcelo Héctor Fuxman Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 180 Silvia Alejandra Rodríguez Tomás Arnaude Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 183 AUDIT COMMITTEE Report of Independent Auditors 344 President Carlos Tovagliari Contact 348 Regular Member Clarisa Lifsic Santiago Alberdi Annual Report Contents Glossary of Terms 8 1. 2016 Results and Future Outlook 12 2. Corporate Governance 19 3. Our Shareholders / Stock Performance 25 4. The Macroeconomic Context 28 5. The Argentine Electricity Market 30 6. The Argentine Oil and Gas Market 53 7. Relevant Events for the Fiscal Year 67 8. Description of Our Assets 80 9. Human Resources 110 10. Corporate Responsibility 113 11. Information Technology 118 12. Quality, Safety, Environment & Labor Health 119 13. Results for the Fiscal Year 122 2016 Annual Report 14. Dividend Policy 148 To the shareholders of Pampa Energía S.A. -

Audit Report, Consolidated Annual Financial Statements, and Consolidated Management Report All for the Year Ended December 31, 2010

AUDIT REPORT, CONSOLIDATED ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS, AND CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT ALL FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2010 TELEFÓNICA, S.A. AND SUBSIDIARIES COMPOSING THE TELEFÓNICA GROUP CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS (CONSOLIDATED ANNUAL ACCOUNTS) AND CONSOLIDATED MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2010 TELEFÓNICA GROUP CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION AT DECEMBER 31 (MILLIONS OF EUROS) ASSETS NOTE 2010 2009 A) NON-CURRENT ASSETS 108,721 84,311 Intangible assets (Note 6) 25,026 15,846 Goodwill (Note 7) 29,582 19,566 Property, plant and equipment (Note 8) 35,797 31,999 Investment properties 5 5 Investments in associates (Note 9) 5,212 4,936 Non-current financial assets (Note 13) 7,406 5,988 Deferred tax assets (Note 17) 5,693 5,971 B) CURRENT ASSETS 21,054 23,830 Inventories 1,028 934 Trade and other receivables (Note 11) 12,426 10,622 Current financial assets (Note 13) 1,574 1,906 Tax receivables (Note 17) 1,331 1,246 Cash and cash equivalents (Note 13) 4,220 9,113 Non-current assets held for sale 475 9 TOTAL ASSETS (A + B) 129,775 108,141 EQUITY AND LIABILITIES NOTE 2010 2009 A) EQUITY 31,684 24,274 Equity attributable to equity holders of the parent 24,452 21,734 Non-controlling interests (Note 12) 7,232 2,540 B) NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES 64,599 56,931 Non-current interest-bearing debt (Note 13) 51,356 47,607 Non-current trade and other payables (Note 14) 2,304 1,249 Deferred tax liabilities (Note 17) 6,074 3,082 Non-current provisions (Note 15) 4,865 4,993 C) CURRENT LIABILITIES 33,492 26,936 Current interest-bearing debt (Note 13) 9,744 9,184 Current trade and other payables (Note 14) 19,251 14,023 Current tax payables (Note 17) 2,822 2,766 Provisions (Note 15) 1,675 963 TOTAL EQUITY AND LIABILITIES (A+B+C) 129,775 108,141 The accompanying Notes 1 to 25 and Appendices I to VI are an integral part of these consolidated statements of financial position. -

Any Redistribution of This Information Is Strictly Prohibited. Copyright © 2017 EMIS, All Rights Reserved. a Euromoney Institutional Investor Company

Any redistribution of this information is strictly prohibited. Copyright © 2017 EMIS, all rights reserved. A Euromoney Institutional Investor company. 2 › Latin American M&A picked up pace in the last sector was oil & gas, which saw two transactions, quarter of 2016 with 386 deals - the highest the more notable of which was Russian oil major quarterly amount during the year but still slightly Rosneft’s purchase of 23% in PetroMonagas for less than in the last quarter of 2015. Overall for USD 500mn. the year the announced deals were 1,456. › M&A in Central America and the Caribbean was › Argentina and Chile were the chief contributors largely unchanged from last year, with a total of for the increased deal flow in Q4 with 40 and 52 129 deals in 2016 (4 deals less y/y). The largest deals, respectively. In Argentina, deal activity transaction was Liberty Global’s purchase of remained flat y/y in the last quarter, while in regionally-focused counterpart Cable & Wireless Chile the number of deals rose by 27%. Communications for USD 4bn (excl. debt). › M&A activity in Brazil, Mexico and Colombia remained mostly unchanged on a quarterly base in the last three months of 2016 but annual drops were reported in all countries. › In Peru (104 deals in 2016, 10 less y/y), a couple of larger deals albeit for small stakes happened in Q4 – notably the additional acquisition of 5.6% in local retailer Falabella by its Chilean parent, and the purchase of 1.6% in gas operator TgP by Spanish sector player Enagas. -

Telecom Italia Capital

Offering Memorandum Confidential TELECOM ITALIA CAPITAL $1,000,000,000 Series A 4% Guaranteed Senior Notes due 2008 Issue price: 99.953% $2,000,000,000 Series B 5.25% Guaranteed Senior Notes due 2013 Issue price: 99.742% $1,000,000,000 Series C 6.375% Guaranteed Senior Notes due 2033 Issue price: 99.558% Guaranteed on a senior, unsecured basis by Telecom Italia S.p.A. Interest payable on May 15 and November 15 The Series A notes will mature on November 15, 2008, the Series B notes will mature on November 15, 2013 and the Series C notes will mature on November 15, 2033. Interest on the notes of each series will accrue from October 29, 2003, and the first interest payment date will be May 15, 2004. Telecom Italia Capital, a société anonyme (“TI Capital”), and Telecom Italia S.p.A. (“Telecom Italia”) may redeem some or all of the notes at any time after May 15, 2005. The redemption prices are described under “Description of Notes and Guarantees — Redemption at TI Capital’s Option”. The notes may also be redeemed at 100% of their principal amount in whole but not in part upon the occurrence of certain tax events described in this offering memorandum. The notes will rank equally with all our existing and future senior debt and rank senior to all our existin g and future subordinated debt. The notes will be fully, unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Telecom Italia. See “Risk Factors” beginning on page 23 for a discussion of certain risks that you should consider in connection with an investment in the notes. -

Global Program for the Issuance of Non-Convertible Notes for a Total Amount of USD 500 Million Or Its Equivalent in Another Currency

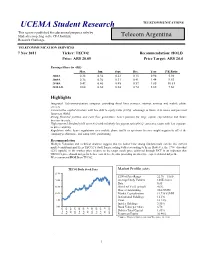

TELECOMMUNICATIONS UCEMA Student Research This report is published for educational purposes only by Students competing in the CFA Institute Telecom Argentina Research Challenge. TELECOMMUNICATION SERVICES 7 Nov 2011 Ticker: TECO2 Recommendation: HOLD Price: ARS 20.05 Price Target: ARS 24.4 Earnings/Share (in ARS) Mar. Jun. Sept. Dec. Year P/E Ratio 2008A 0.28 0.34 0.22 0.13 0.98 5.98 2009A 0.36 0.36 0.31 0.41 1.44 9.53 2010A 0.42 0.46 0.45 0.52 1.85 10.81 2011A/E 0.64 0.60 0.64 0.74 2.62 7.66 Highlights Integrated Telecommunication company: providing fixed lines services, internet services and mobile phone services Conservative capital structure with low debt to equity ratio (0.9%): advantage in future debt issues and potential future tax shield Strong financial position and cash flow generation: better position for large capital expenditures and future increase in costs. High expected dividend yield (over 8%) with relatively low payout ratio (60%): attractive return with less exposure to price volatility Regulatory risks: future regulations over mobile phone tariffs or spectrum licenses might negatively affect the company performance and competitive positioning Recommendation Multiple Valuation and technical analysis suggest that no bother how strong fundamentals can be, the current market conditions may keep TECO2´s stock from reaching values according to them. However, the 17%+ discount (22% upside) in the market price relative to the target stock price achieved through DCF is an indicator that TECO2´s price should not go far below current levels, also providing an attractive expected dividend yield. -

Annual Report 2004 Court of Justice of the European Communities

06 ISSN 1680-8304 QD-AG-05-001-EN-C ANNUAL REPORT 2004 COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2004 COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES EN 00_2005_0419_cover_EN 1 28-02-2005, 11:23 COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Synopsis of the Work of the Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance of the European Communities Luxembourg 2005 www.curia.eu.int 1 Court of Justice Table of contents Court of Justice of the European Communities L-2925 Luxembourg Telephone: (352) 43 03-1 Telex (Registry): 2510 CURIA LU Telefax (Court): (352) 43 03-2600 Telefax (Information Service): (352) 43 03-2500 Court of First Instance of the European Communities L-2925 Luxembourg Telephone: (352) 43 03-1 Telefax (Court): (352) 43 03-2100 Internet: http://www.curia.eu.int Completed on: 21st January 2005 A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2005 ISBN 92-829-0748-1 © European Communities, 2005 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Italy PRINTED ON WHITE CHLORINE-FREE PAPER 2 3 Court of Justice Table of contents Table of contents Page Foreword, by Mr Vassilios Skouris, President of the Court of Justice ........................... 5 Chapter I The Court of Justice of the European Communities A — The Court of Justice in 2004: changes and proceedings .................................... -

Resumen Sustentabilidad GW-V7

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT Our Mission With transparency, honesty, work, research and investment, we seek to contribute to the well-being of society, contributing our tools to transform the present looking out towards the future. Through the Leo Werthein Foundation we promote actions in 3 axes: EDUCATION ART AND ENVIRONMENT CULTURE We have the support of various institutions: > United Nations. > World Bank. > Scholas Occurrentes. >ORT > Ministry of Education of the Government of the City of Buenos Aires. > Banco Santander. > Among others. EDUCATION Youth Meetings - Scholas World ORT These meetings encourage young people from various cities of the world to discover the transformative power of education with methodological tools that led to their respective communities through their Art, Play and Thought. Website - 2021 Website, memory and virtual platform for the World Youth Meeting. Mexico Meeting - 2019 More than 200 youths from 26 cities around the world participated along with Mexican President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. The meeting contained a message devoted to them by Pope Francis. Buenos Aires Meeting - 2018 More than 500 participants from 30 cities around the world participated along with the head of the Buenos Aires Government. The meeting contained a message specially recorded by Pope Francis. Global Citizenship 2019/2020/2021 It is an educational program that promotes quality education to contribute to the formation of a global citizenship, measured by digital technologies, for the construction of a fairer, more equitable and sustainable future. This program is developed by the Ministry of Education of the City of Buenos Aires while the Leo Werthein Foundation contributes to the integral development of the digital platform and cross-media content. -

The Faceless Court

THE FACELESS COURT ANGELA HUYUE ZHANG* ABSTRACT This Article is the first to examine the behavior of judges and their law clerks (officially entitled référendaires) at the Court of Justice of the European Union. It identifies a number of serious is- sues affecting Court performance. First, the Article finds that the Court's high judicial salaries and lack of procedural safeguards for EU judicial appointments attract political appointees. As a conse- quence, some judges who are selected are not competent to per- form their duties and are dominated by their référendaires. More- over, the high turnover rate of EU judges hampers their productivity and increases their dependence on the référendaires. * Senior Lecturer (associate professor equivalent) in competition law & trade, King’s College London. J.D. & J.S.D., University of Chicago Law School. I thank the workshop participants at King’s, Berkeley, Stanford, LSE, and UEA as well as the conference participants at the twenty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Law and Economic Association and the First Conference on Empirical Legal Stud- ies in Europe for insightful comments on earlier drafts. I am also indebted for comments from Judge Posner, Alison Jones, Wouter Wils, Richard Whish, Pablo Ibanez-Colomo, Rosa Greaves, Oana Stefan, Christopher Townley, Eleanor Fox, Valentine Korah, Carl Baudenbacher, John Temple Lang, Nicolas Petit, Laurence Idot, Shai Dothan, David Elliot, David Stallibrass, Wentong Zheng, Daniel Sokol, and David Bailey. Special thanks to Luxi Ye, Catherine Derenne, Marta Matnynia, Helin Laufer, and Eugenia Caracciolo-Drudis for their excellent research assis- tance. I am obliged to the British Academy for funding this research. -

1 ATTACHMENT 1 Joint International and Domestic Section 214

ATTACHMENT 1 Joint International and Domestic Section 214 Application to Transfer Control of Telecom Argentina USA, Inc. This joint application seeks Federal Communications Commission (“FCC” or “Commission”) consent under Section 214 of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (the “Act”), and Sections 63.04 and 64.24 of the Commission’s rules1 to transfer control of Telecom Argentina USA, Inc. (“Telecom Argentina USA”) from Telecom Italia S.p.A. (“Telecom Italia” or “Transferor”) to Fintech Advisory, Inc. (“Fintech Advisory” or “Transferee”). Telecom Argentina USA holds an international Section 214 authorization as well as blanket Section 214 domestic operating authority. As explained further below, grant of the application serves the public interest. I. REPONSES TO QUESTIONS SET FORTH IN THE FCC 214 MAIN FORM Responses to certain questions set forth in the application’s FCC 214 Main Form are as follows: Answers to Question 10 Transferor Contact Information Transferee Contact Information Lorenzo Canu Erika Mouynes Telecom Italia SpA General Counsel Corso d’Italia 41 Fintech Advisory, Inc. 00198 Rome – Italy 375 Park Avenue, 38th Floor Tel: +39.06.36882634 New York, NY 10152 Fax: +39.06.41863959 Tel. 212-593-3536 [email protected] Fax 212-593-3461 [email protected] With a copy to: With a copy to: Colleen King Amy Worlton Cheryl A. Tritt Wiley Rein LLP Jennifer L. Kostyu 1776 K Street, NW Wilkinson Barker Knauer, LLP Washington, D.C. 20006 2300 N Street, N.W., Suite 700 Tel. 202-719-7307 Washington, D.C. 20037 Fax 202-719-7049 Tel. 202-783-4141 [email protected] Fax 202-783-5851 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 47 U.S.C. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

2018 Annual Report and Financial Statements 2018 Annual Report and Financial Statements BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Marcos Marcelo Mindlin Index Vice-Chairman Gustavo Mariani Director Ricardo Alejandro Torres Damián Miguel Mindlin Gabriel Cohen Diana Mondino Santiago Alberdi 01 02 Carlos Tovagliari Diego Martín Salaverri Annual Report Consolidated Miguel Bein Financial Statements Alternate Director José María Tenaillon Mariano Batistella Glossary of Terms 8 Glossary of Terms 164 Pablo Díaz Isaac Héctor Mochón Consolidated Statement 168 of Comprehensive Income Nicolás Mindlin Brian Henderson Consolidated Statement 170 Victoria Hitce of Financial Position Enrique Luján Benítez María Carolina Sigwald Consolidated Statement 172 Mauricio Penta of Changes In Equity Consolidated Statement 174 of Cash Flows SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Notes to the Consolidated 175 Statutory Auditor Germán Wetzler Malbrán Financial Statements José Daniel Abelovich Martín Fernández Dussaut Alternate Statutory Auditor Marcelo Héctor Fuxman Tomás Arnaude 03 04 AUDIT COMMITTEE Report of 320 Contact 324 Regular Member Carlos Tovagliari Diana Mondino Independent Miguel Bein Auditors Alternate Member José María Tenaillon Isaac Héctor Mochón Enrique Luján Benítez 01 Annual Report Contents Glossary of Terms 8 01. 2018 Results and Future Outlook 12 02. Corporate Governance 18 03. Our Shareholders / Stock Performance 25 04. Macroeconomic Context 28 05. The Argentine Electricity Market 30 06. The Argentine Oil and Gas Market 54 07. Relevant Events for the Fiscal Year 69 08. Description of Our Assets 90 09. Human Resources 118 10. Corporate Responsibility 121 11. Information Technology 126 12. Quality, Safety, Environment and Labor Health 127 13. Results for the Fiscal Year 131 14. Dividend Policy 145 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 15.