Adobe Photoshop Techniques, Tips & Tutorials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using GIMP to Create an Artistic Regional RPG Map – Part 5

Using GIMP to Create an Artistic Regional RPG Map – Part 5 This tutorial series is an updated and revised edition of an original tutorial created by RobA for the Cartographer’s Guild (www.cartographersguild.com). Updates and revisions to the instructions, along with new screenshots, were created by Megan Wiseman (“wisemoon” on Cartographer’s Guild). Part 1 gave instructions on how to create the basic landmass outline for your map, including some ideas on how to randomly generate a landmass shape if you don’t have a sketch to start with. Part 2 gave instructions on how to color your ocean/sea, and how to color your landmass with textured grass and dirt. Part 3 gave instructions on how to create mountains and forests on your map. Part 4 gave instructions for how to create rivers and lakes on your map, and also showed you how to create cities and roads. This part of the tutorial will show you how to label your geographical features and cities. Then we’ll show you how to create a nifty title for your map. You can create a legend for your map in the same basic way you create the title. You can also add a compass rose. We’ll finish it off with a simple border. Adding Labels to Your Map Every map has labels for various geographical features, as well as labels for cities, towns and other settlements. Most of the horizontal text labels will be made using the text tool, just like the city icons were done in Part 4. -

18 595954 Bindex.Qxd 6/14/05 11:07 AM Page 639

18_595954 bindex.qxd 6/14/05 11:07 AM Page 639 Index A masking and unmasking effects, hiding, 149 Actions palette 222–225 transparent, 151 action sets, 557, 565 This Layer slider, 229, 230, 232, Bas Relief filter, 359, 360 batch processing with actions, 235, 237 Batch command, 566, 568–569 566–570 Transparency Shapes Layer batch processing. See also Actions commands not recorded by, 560 option, 222–223, 225 palette deleting operations, 563 Underlying Layer slider, 229, 230, actions for, 566–570 editing actions, 560–563 231, 233, 234, 236–237 Auto commands for, 514 forcing a command to record, 562 Vector Mask Hides Effects option, Camera Raw images, 585 inserting stops, 562 222–223, 225 checking for the first image, 570 leaving a setting open, 562 Aligned check box Color Settings command and, 568 loading action sets, 565 Clone Stamp tool, 51–52, 87 defined, 566 naming actions, 558 Healing Brush tool, 58 maximizing performance, 569 naming sets, 559 pattern painting tools, 74 renaming files, 552–553, 569 overview, 557 animated GIF images, 623–626 Batch Rename command (Bridge), playing actions and operations, anti-aliasing 552–553 563–565 for Color Replacement tool, 485 Behind brush mode, 38, 182 recording actions, 557–560 for layer effects, 265 Bevel layer effect, 255, 257, 258 saving action sets, 565 Lens Blur filter and, 315 blend modes. See also blending undoing actions, 565 Art History brush Add Noise filter with, 321, 323 Adaptive color palette, 608–609 Canvas texture with, 99 adjustment layers for, 488–489 Add Noise filter options unique -

Decomposing Images Into Layers with Advanced Color Blending

Pacific Graphics 2018 Volume 37 (2018), Number 7 H. Fu, A. Ghosh, and J. Kopf (Guest Editors) Decomposing Images into Layers with Advanced Color Blending Yuki Koyama and Masataka Goto National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Japan Boom layer Top layer (N/A) normal hard-light multiply Input image Decomposed layers Edited image Figure 1: Our method decomposes an input image (Left) into layers that can reproduce the image by composition with advanced color-blend modes such as hard-light and multiply (Middle). Users can specify the color-blend mode and desired color distribution for each layer, as well as the number of layers. Output layers are useful for non-trivial image manipulation such as lighting-aware color editing (Right). Input image courtesy of David Revoy. Abstract Digital paintings are often created by compositing semi-transparent layers using various advanced color-blend modes, such as “color-burn,” “multiply,” and “screen,” which can produce interesting non-linear color effects. We propose a method of decomposing an input image into layers with such advanced color blending. Unlike previous layer-decomposition methods, which typically support only linear color-blend modes, ours can handle any user-specified color-blend modes. To enable this, we generalize a previous color-unblending formulation, in which only a specific layering model was considered. We also introduce several techniques for adapting our generalized formulation to practical use, such as the post-processing for refining smoothness. Our method lets users explore possible decompositions to find the one that matches for their purposes by manipulating the target color-blend mode and desired color distribution for each layer, as well as the number of layers. -

SVG) 1.0 Specification W3C Candidate Recommendation 02 November 2000

next contents properties index Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.0 Specification W3C Candidate Recommendation 02 November 2000 This version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20001102/ (Available as: PDF, zip archive of HTML) Latest version: http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG/ Previous version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/CR-SVG-20000802/ Editor: Jon Ferraiolo <[email protected]> Authors: See author list Copyright ©1998, 1999, 2000 W3C® (MIT, INRIA, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark, document use and software licensing rules apply. Abstract This specification defines the features and syntax for Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), a language for describing two-dimensional vector and mixed vector/raster graphics in XML. Status of this document The Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.0 specification is still in the Candidate Recommendation phase. This new draft specification is being published to reflect minor changes to the specification and editorial updates resulting from implementation feedback. The SVG Working Group (Members-only) considers the specification to be stable and encourages implementation and comment on the specification during this period. The Candidate Recommendation review period ends when there exists at least one SVG implementation which passes each of the Basic Effectivity (BE) tests in the SVG test suite. The implementation status of SVG is already very good, and at this point, most of the test are passed by one or multiple implementations, but as yet the exit criteria have not been met. It is anticipated that implementation status will be such that the exit criteria will be met in approximately one month. Please send review comments before the review period ends to [email protected]. -

GPU-Accelerated Path Rendering

Computer Graphics Proceedings, Annual Conference Series, 2012 GPU-accelerated Path Rendering Mark J. Kilgard Jeff Bolz NVIDIA Corporation∗ Figure 1: GPU-accelerated scenes rendered at super-real-time rates with our system: Snail Bob Flash-based game (5ms) by permission of Andrey Kovalishin and Maxim Yurchenko, Van Gogh SVG scene with gradients (5.26ms) by permission of Enrique Meza C, complete (shown clipped) SIGGRAPH web page (4.8ms), and SVG scene with path clipping (1.9ms) by permission of Michael Grosberg, all rendered on a GeForce 560M laptop. Abstract When people surf the web, read PDF documents, interact with smart phones or tablets, use productivity software, play casual For thirty years, resolution-independent 2D standards (e.g. games, or in everyday life encounter the full variety of visual output PostScript, SVG) have depended on CPU-based algorithms for the created digitally (advertising, books, logos, signage, etc.), they are filling and stroking of paths. Advances in graphics hardware have experiencing resolution-independent 2D graphics. largely ignored accelerating resolution-independent 2D graphics rendered from paths. While 3D graphics dominates graphics research, we observe that most visual interactions between humans and computers involve We introduce a two-step “Stencil, then Cover” (StC) programming 2D graphics. Sometimes this type of computer graphics is called interface. Our GPU-based approach builds upon existing tech- vector graphics, but we prefer the term path rendering because the niques for curve rendering using the stencil buffer, but we explicitly latter term emphasizes the path as the unifying primitive for this decouple in our programming interface the stencil step to deter- approach to rendering. -

Notes Taken from Affinity Photo Tutorial Videos

Notes taken from Affinity Photo tutorial videos Affinity Photo https://affinity.serif.com/en-gb/photo/ Latest tutorial videos http://affin.co/PhotoTuts The tutorial set includes: Beginners Series Opening & Saving File [menu] - Open - opens any supported photo format file File [menu] - Save - overwrites open file - destructive overwrite of an image File [menu] - Save As – only saves in Affinity file format ".afphoto" with layers etc. Layers Use layers for non-destructive image processing - Can be readjusted, reordered or turned off Adjustments Add adjustment by: Layer [menu] - New Adjustment Layer - Brightness and Contrast - Then adjust settings, close adjustments dialog - Reopen adjustment dialog by double clicking the icon in Layers panel Common adjustments Brightness and contrast - basic brightness and contrast HSL - hue, saturation, lightness - color shift, saturation, brightness Selective color - selectively change colors Exposure - brightness Black and White - adjust contribution of each color to B&W mix Levels - set Black and White points Filters Blur, sharpen, etc. Filters need to be applied to a pixel layer, otherwise will have no effect FILTERS ARE DESTRUCTIVE – use Layer - Live Filters for non-destructive filters Live Filters can be reordered by dragging in layer stack - Common filters Haze removal - Common Live Filters – by default are nested into pixel layer they apply to Vignette - darken corners Perspective - geometric distortion correction Lighting - add a light source - control direction, spread etc. of light Exporting Write out standard image format files File [menu] - Export - pick file format, set options, and click Export, navigate to the destination folder and enter filename, click Save Use the Export persona for more control Introduction Discover Affinity Photo Tools panel on left side - brushes etc. -

Reflecting on Blend Modes

THE ADOBE® PHOTOSHOP® “HOW-T0” MAGAZINE › › JUNE/JULY 2020 When retouching fashion images, Blending modes can be used to Photo agency standards are progressively create cool type effects from writing on a Designing in Effects moving toward a more natural look chalkboard to painting letters on a street Photoshop ® Dave Thurau | KelbyOne Member REFLECTING ON BLEND MODES Learn what lies beneath the surface of blending modes in Photoshop Do you have better photos inside you, just waiting to get out? This book can help. A totally updated version of the #1 best-selling digital photography book of all time! KelbyOne Pro members: Use your discount code at rockynook.com to get 50% off your purchase Every time you turn the page, you’ll learn another pro setting, tool, or trick to transform your work from snapshots into gallery prints. If you’re tired of taking shots that look “okay,” and if you’re tired of looking in photography magazines and thinking, “Why don’t my shots look like that?” then this is the book for you. | kelbyone.com | rockynook.com | #kelbyonebooks [ PHOTOSHOP USER • JUNE/JULY 2020 • VOL 23 • NO 6 ] CONTENTS ; Layout: Jessica Maldonado Jessica Layout: ; Background Images: © Adobe Stock and Unsplash Stock Adobe © Images: Background [052] BLENDING MODES EXPLAINED FEATURE By Scott Valentine Scott Valentine loves blending modes, which show up in just about every professional technique and workflow in Photoshop, ranging from photographic corrections and effects to graphic design and illustration. Scott was delighted when we asked him to be our tour guide through these absolutely essential capabilities in Photoshop. -

Layer Blending Modes

Layer Blending Modes lend Modes can be used to tell layers how to interact with layers beneath them in dif- ferent ways. By setting Blend Modes you can make paint darken paint below, tint it, or oth- erwise adjust it. ArtRage provides a number of Blend Modes, including the standard ones from Adobe Photoshop and some of its own. The default Blend Mode applied to each Layer is “Normal”, which means that paint will sit on top of paint on the layer beneath and cover it like normal paint on a surface. To use layer blend modes you have to have two or more layers. The blend mode will react with the layer below it. For this tutorial I will be using an image with two layers. The blending mode will be applied to the top layer and we'll look at the way they both interact. The background layer is a picture I took on a holiday in one of my favourite places in Bel- gium. The one I will use for the layer modes is made of some grayscale and colour sam- ples. The tint mode takes the color of the paint on your lay- er and tints the paint underneath it. In this example the blue sample has applied a blue tint to the Photo beneath. Use this mode if you want to apply color to something in gray scale, or tint the color below with a new color above. The highlight blend lightens paint beneath it, allowing you to make paint brighter by applying paint above it without washing it out to plain white. -

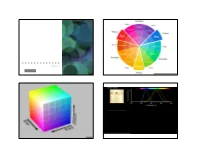

CS467 Lecture 2

CS 467 GENERATIVE ART Color Spring 2020 http://blog.canvascorpbrands.com/tattered-tangles-color-me-cards-book-tags/ RGB Cube, SharkD CRT Displays LCD / LED displays Plasma displays image from F. Hill “Computer Graphics Using OpenGL” image from http://www.laptop-lcd-screen.co.uk/ laptopparts/what-is-lcd-how-laptop-screen-works.asp image from http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/plasma-display2.htm images from E. Angel and D. Shreiner “Interactive Computer Graphics” Hue Saturation Value [or Brightness] (HSV/HSB) Hue Saturation Lightness (HSL) HSV Cone, Wikimedia Commons RGBA Blend modes D - destination pixel S - source pixel Blend Mode Behavior BLEND D’ = D * (1-alpha) + S * alpha ADD D’ = D + S * alpha DARKEST D’ = min(S * alpha, D) LIGHTEST D’ = max(S * alpha, D) DIFFERENCE D’ = max( D - S*alpha, S*alpha - D) EXCLUSION similar to DIFFERENCE but “less extreme” MULTIPLY D’ = D * S*alpha SCREEN D’ = 1 - ((1 - D) * (1 - S)) REPLACE D’ = S REMOVE remove pixels from D with alpha strength of S OVERLAY Mix of MULTIPLY and SCREEN, multiplies dark values, screens light values HARD_LIGHT SCREEN when > 50% gray, MULTIPLY when lower SOFT_LIGHT Mix of DARKEST and LIGHTEST. Woks like OVERAY, but not as harsh Red DODGE D’ = D / (1 - (S * alpha)), lightens light tones, increases contrast, ignores darks BURN D’ = 1 - ((1-D) / (S*alpha)), darkens dark tones, increases contrast, ignores lights Green Blue https://p5js.org/reference/#/p5/blendMode Alpha https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Canvas_API/Tutorial/Compositing aliceblue #f0f8ff darkslategrey -

Manual Contents

Flair for After Effects v1.1 manual Contents Introduction . .3 Common Parameters . .4 1. Amiga Rulez . 11 2. Box Blur . 15 3. Glass Sphere . 18 4. Glow . .23 5. Highlight . .26 6. Mosaic Plane . .29 7. Radial Blur . 32 8. Volumetrics . .36 Copyright Notice . .39 2 Introduction This is the manual for the Flair fi lter package. It explains the functionality and provides you with hints and tips how to use the fi lters properly. The Flair fi lter set contains the following plug-ins: 1. Amiga Rules 2. Box Blur 3.3. GlassGlass SphereSphere 4. Glow 5. Highlight 6. Mosaic Plane 7. Radial Blur 8. Volumetrics 3 Common Parameters Several parameters occur in multiple filters but not in all of them. This is an overview of common parameters in Flair. Show parameter Blend parameter Color Bias Channel Control Selection 4 ‘Show parameter’ This parameter is used to see alternative views or additional information about the filter. Currently there are just these two extra modes to see your selection. ‘normal’ Normal effect view. ‘selected footage’ Show all the footage that has been selected. Non-selected footage is blended out. ‘selection only’ Show the selection only as a grayscale image. White color indicates a completely selected pixel. Darker values indicated particaly selected pixels. ‘Blend parameter’ Filters with this parameter can blend their results with the source image. Several blend modes are available which are described here. Please note that these blending not necessarily act exactly like those in After Effects. ‘normal’ This is regular alpha blending. ‘max weight’ Source image and effect result are weighted using the maximum channel value of the effects image. -

Blend Modes Explained

Search PHOTOSHOP TUTORIALS Beginners | Intermediate BLENDING MODES NOTE (The majority of the following information can also be found in the program's Help files, and I take no personal credit for writing it. I have converted it to HTML and posted it here simply as a convenience for my visitors, and to supplement other content.) Please give the image samples a few extra seconds to download, this is a long page. But the information needs to be all on one page so you can compare the Blend Modes against each other. Read the following while you're waiting... Layers You use layer blending modes to determine how the pixels in a layer are blended with underlying pixels on other layers. By applying specific blend modes to individual layers, you can create a wide variety of special effects. NOTE There is no Clear blending mode for layers; as is found in the 'Stroke' filter for instance. In addition, the Color Dodge, Color Burn, Darken, Lighten, Difference, and Exclusion modes are unavailable for Lab images. Painting & Editing Tools The blending mode specified in the Options palette for each tool controls how pixels in the image will be affected by tools. It’s helpful to think in terms of the following colors when visualizing a blending mode’s effect: The 'Base color' is the original color in the image. The 'Blend color' is the color being applied with the painting or editing tools. The 'Result color' is the color resulting from the blend mode used. Blend Mode Descriptions Page 1 These mode types are based on the latest version of Photoshop, but their effects are universal in all versions. -

Imageen, Image Display and Editing Library for Delphi, C++ Builder and .NET

ImageEn, Image Display and Editing Library for Delphi, C++ Builder and .NET Current Version: 4.3.0 Released: 4 Feb. 2013 ImageEn is the most powerful native image library available for Delphi and C++ Builder, and is also available for .NET. The library includes a complete suite of components to handle all aspects of image and editing, analysis and display. Join thousands of other developers who rely on ImageEn to add professional multimedia functionality to their software. Compatibility Delphi 5 - XE3 (32/64 bit), C++ Builder 5 - XE3 (32/64 bit) and .NET 2.0 - 4.0. Test our features with 130 Compiled Demos File Operations Asynchronous loading and saving Lossless JPEG rotation and cropping Support for Color Management Systems to process ICC profiles Loading and saving of digital camera (EXIF) fields in JPEG, TIFF, RAW and HD Photo files (without modifying the original image) Loading and saving of EXIF GPS fields Loading and saving of Adobe XMP fields from JPEG, TIFF, HD Photo and PSD files Raw camera support including access to internal thumbnails and other data fields Loading and saving of IPTC data (most commonly used by Photoshop) from JPEG and TIFF files (without modifying the original image) Quick reading of image properties (dimensions, color depth, etc) without loading image Image load and save dialogs which include a preview and relevant save settings http://www.imageen.com/info/Index.html#IEVision[2013/3/28 下午 05:25:09] ImageEn, Image Display and Editing Library for Delphi, C++ Builder and .NET Support for alpha channel in GIF, TIFF, PNG, ICO, CUR, TGA, PSD files Load images directly from the internet (using http/ftp protocol) Encryption and decryption using a 128 bit key Image Display Images can be automatically displayed "To-Fit" or with real time zoom.