Center for the Rule of Law in Support of Petitioner ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Transcript

BOOK-2020/02/24 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM CODE RED: A BOOK EVENT WITH E.J. DIONNE JR. Washington, D.C. Monday, February 24, 2020 Conversation: E.J. DIONNE JR., W. Averell Harriman Chair and Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution ALEXANDRA PETRI Columnist The Washington Post * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 BOOK-2020/02/24 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. DIONNE: I want to welcome everybody here today. I’m E.J. Dionne. I’m a senior fellow here at Brookings. The views I am about to express are my own. I don’t want people here necessarily to hang on my views. There are so many people here. First, I want to thank Amber Hurley and Leti Davalos for organizing this event. I want to thank my agent, Gail Ross, for being here. You have probably already seen one of the 10,500,000 Mike Bloomberg ads; you know the tagline is “Mike Gets it Done.” No. Gail gets it done (laughter), so thank you for being here. One unusual person I want to -- also, another great book that you have to read, my friend, Melissa Rogers, who’s a visiting scholar here, we worked together for 20 years, her book, “Faith in American Public Life,” which has a nice double meaning, is a great book to read. And, I can't resist honoring my retired Dr. Mark Shepherd who came here today. -

Congressional Record—House H9262

H9262 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE October 7, 2003 perfect movie Hollywood couple that America’s last half century, to have land Athletics and she passed away in her just loved each other and did not mind raised three wonderful sons and two sleep. expressing that love in front of every- outstanding daughters. Tommy, who I Millie O’Neill was an incredible woman who body. met at Boston College; Susan, who was was not often recognized for the selfless work I had the opportunity for 12 consecu- my classmate and a history major with she did for Congress and our country. Mr. tive years to travel with Tip O’Neill as me at Boston College. I have known Speaker, I want to call attention to two things he was invited around the world as them my whole life. that Mrs. O’Neill was instrumental in achiev- Speaker; but I do not know whether it This is a wonderful family, and they ing. The first was a massive fundraising effort was Tip or Millie, but one thing was balanced the demands of that journey on behalf of the Ford’s Theatre Foundation, abundantly clear, that they were not against the love and attention that a raising over $4 million dollars, for which Millie Democratic trips. They were not Re- family requires. And Millie emerged was recognized at a Gala dinner in 1984. publican trips. It was traveling with from it all with her love for Tip as The second item that I believe Mrs. O’Neill Millie and Tip O’Neill, and they made strong and as deep and as transparent deserves to be recognized for was ensuring everyone feel like just one big congres- as the two schoolkids they once were. -

Frank, Barney (B

Frank, Barney (b. 1940) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Barney Frank. United States congressman Barney Frank is known for his intelligence, his quick and acerbic wit, and his spirited defense of his social and political beliefs. He has been a leader not only in the cause of gay and lesbian rights, but also on issues including fair housing, consumer rights, banking, and immigration. Frank was born on March 31, 1940 in Bayonne, New Jersey, where his father owned a truck stop. As a youngster Frank developed an interest in politics. He did not, however, foresee a career in government for himself because he observed in politics a dismaying amount of corruption and an inhospitable attitude toward Jews. He had, moreover, realized at the age of thirteen that he was gay, which also seemed an obstacle to a political career. Nevertheless, Frank remained an avid student of politics. After receiving a bachelor's degree from Harvard in 1962, he entered the university's graduate program in political science. In addition to offering courses in government from 1963 to 1967, he worked as the assistant to the director of the Institute for Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government in 1966 and 1967. Frank left the graduate program in 1967 to work on Kevin White's campaign to become mayor of Boston. Following White's victory, Frank was his executive assistant for three years and then spent a year as an administrative assistant to Representative Michael J. -

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts

~ THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ONE ASHBURTON PLACE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02108 MARTHA COAKLEY (617) 727-2200 www.mass.gov/ago ATTORNEY GENERAL November 24,2008 The Honorable Edward M. Kennedy, Chairman Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions 428 Senate Dirksen Offce Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Re: Senate 20, "The Protecting Patients and Health Care Act" Dear Senator Kennedy: As you are aware, last week Senator Hilary Rodham Clinton and Senator Patt Murray introduced Senate 20, A Bil to Prohibit the Implementation or Enforcement of Certain Regulations. I am writing to express my strong support for Senate 20, referred to as the "Protecting Patients and Health Care Act," and my continued opposition to the United States Department of Health and Human Services' proposed "provider conscience" regulations. The bil was referred to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions on November 20,2008. Senate 20 prevents the Secretary of Health and Human Services from finalizing, enforcing, implementing, or taking other action in furtherance of the proposed regulations, which are available at 73 Fed. Reg. 50274 (August 26,2008), section 245 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 238n), and section 508(d) of division G of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 (Public Law 110-161). Attached for your reference please find a copy of the September 19, 2008 letter I submitted to Secretary Leavitt in opposition to the proposed regulations. Senate 20 is timely and critical to protecting patients' access to basic reproductive health care services and information. Accordingly, I ask the Committee to report the Protecting Patients and Health Care Act to the entire Senate for passage. -

POLITICAL BRIEFINGS Below Is an Outline of Your Briefi

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu October 9, 1992 MEMORANDUM TO THE LEADER FROM: JOHN DIAMANTAKIOU SUBJECT: POLITICAL BRIEFINGS Below is an outline of your briefing materials for your appearances in New England and New York. Enclosed for your perusal are: 1. Campaign briefing: • overview of race • biographical materials • Bills introduced in 102nd Congress 2. National Republican Senatorial Briefing 3. City Stop/District race overview 4. Governor's race brief (NH, VT) 5. Redistricting map/Congressional representation 6. NAFTA Brief 7. Republican National Committee Briefing 8. State Statistical Summary 9. State Committee/DFP supporter contact list 10. Clips (courtesy of the campaigns) 11. Political Media Recommendations (Clarkson also has a copy) Thank you. Page 1 of 62 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu BOB DOLE KANSAS Wntteb ~tates ~enate OFFICE OF THE REPUBLICAN LEADER WASHINGTON, DC 20510-7020 OCTOBER 9, 1992 SENATOR: The Torkildsen campaign would like you to stress Peter's integrity, honesty and commitment to public service. They would like you to stay away from mentioning Congressman Mavroules' corruption charges. As a state legislator, Peter was a vocal opponent to then-Governor Dukakis' tax increases and will continue to be a tax-fighter on Capitol Hill. JOHN D. Page 2 of 62 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 10-01-1992 03: 28PM FROM TORK I LDSEN COt"iGRES'.3 1992 TO 12022243163 P.02 MEMORANDUM To: John Oiamantakiou From: Mike Armini Date: 10/1/92 Re! Torkildsen Campaign Background Themes and Issues: Peter is running as a fiscal conservative and a reformer. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 19A60 In the Supreme Court of the United States _______________________________ DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Applicants, v. SIERRA CLUB, ET AL. _______________________________ MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF AND BRIEF OF FORMER MEMBERS OF CONGRESS AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING MOTION TO LIFT STAY _______________________________ Douglas A. Winthrop Irvin B. Nathan Counsel of Record Robert N. Weiner ARNOLD & PORTER Andrew T. Tutt KAYE SCHOLER LLP Kaitlin Konkel 10th Floor Samuel F. Callahan Three Embarcadero Center ARNOLD & PORTER San Francisco, CA 94111 KAYE SCHOLER LLP (415) 471-3100 601 Massachusetts Ave., NW [email protected] Washington, DC 20001 (202) 942-5000 [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae No. 19A60 In the Supreme Court of the United States _______________________________ DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Applicants, v. SIERRA CLUB, ET AL. _______________________________ MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF _______________________________ Amici curiae, a bipartisan group of more than 100 former Members of Congress, move for leave to file the accompanying brief in support of plaintiffs’ motion to lift this Court’s July 26, 2019 stay of the injunction issued by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in this case.1 Amici filed briefs supporting plaintiffs in the district court and the court of appeals in the proceedings both before and after this Court’s stay. Plaintiffs now seek to lift this Court’s July 2019 stay to ensure that the defendants cannot complete their unauthorized construction activities before this Court can act on a petition for a writ of certiorari. -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks at a Democratic

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks at a Democratic National Committee Dinner in Boston, Massachusetts April 1, 2010 The President. Hello, everybody. Thank you. Please, everybody, be seated. Let me just begin by acknowledging some great friends. First of all, somebody who I consider one of the finest Governors in the country, and somebody who I know you guys are going to reelect, Governor Deval Patrick is in the house. To the Massachusetts congressional delegation—I see Ed Markey here, but I want to—I know I saw Congressman Delahunt and Capuano earlier. They have shown such courage and have stuck to it in some very difficult circumstances and are consistently showing the kind of leadership we need. We now got Barney Frank who is about to make sure that we've got financial regulatory reform, which is going to be so critical. So to your congressional delegation, please give them a big round of applause, and Ed Markey in particular. To my dear friend who has been a constant source of inspiration—Vicki Kennedy is here, and I want everybody to give her a big round of applause. And to all of you who cochaired this elegant event, I assure you I will not break out into song. [Laughter] I want to thank Tim Kaine for not only the generous introduction, not only for being an extraordinary Governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia, but also now being one of the best leaders of our party that we've ever had. Some of you may know, Tim Kaine was the first person, the first elected official outside of Illinois to endorse me when I announced my Presidential race—[applause]—on the steps of the old capitol of the Confederacy in Richmond in February of 2007, where most people couldn't pronounce my name. -

Barney Frank

For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] Barney Frank Topics Economics and Finance, Jewish Interest, Leadership, Legal Affairs, Politics and Pundits Travels From Massachusetts Bio Barney Frank served as a US Congressman from 1981-2013 and Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee from 2007-2011. While in Congress, Barney worked to adjust America’s spending priorities to reduce the deficit by providing less funding for the military, thereby protecting funding for important quality-of-life needs at home. In particular, he focused on providing aid to local communities and to building and preserving affordable rental housing for low-income people. He was also a leader in the fight against discrimination of various sorts. He championed the interests of the poor, the underprivileged, and the vulnerable, and he won reelection 16 times by double-digit margins. As Chair of the House Financial Services Committee, Barney was instrumental in crafting the short-term $700 billion rescue plan in response to the mortgage crisis, and he then worked for the adoption of a sweeping set of financial regulations aimed at preventing a recurrence. He was co-author of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the regulatory overhaul signed into law in July 2010. He also led passage of the Credit Cardholders’ Bill of Rights Act, a measure that drew praise from editorial page 1 / 4 For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] boards and consumer advocates. -

2016 AR Print.Pdf

The National Low Income Housing Coalition is dedicated solely to achieving socially just public policy that assures people with the lowest incomes in the United States have affordable and decent homes. 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO. .6 2016 NLIHC HIGHLIGHTS ..........................................................8 2016 MEDIA ...................................................................10 SHEILA CROWLEY RETIRES FROM NLIHC ..................................................12 NLIHC LEADS ..................................................................14 2016 NLIHC STATE PARTNERS .....................................................15 A NEW LEADER FOR NLIHC .......................................................16 OUT OF REACH 2016 ............................................................18 THE GAP REPORT 2016 ..........................................................20 TENANT TALK SPRING & FALL 2016 ................................................22 HOUSING SPOTLIGHT 2016 .......................................................23 2016 LEADERSHIP AND ORGANIZING AWARDS ......................................24 “EVICTED” LIVE-STREAM EVENT. .26 HOUSING TRUST FUND ..........................................................27 2016 BOARD OF DIRECTORS .....................................................28 NLIHC STAFF ...................................................................29 2016 SPECIAL MEMBERS .........................................................30 2016 NLIHC MEMBERS ...........................................................31 -

Barney Frank It’S Not the System, It’S the Voters October 31, 2013

5. Barney Frank It’s Not the System, It’s the Voters October 31, 2013 Introduction ur guest today is a distinguished politician whom I’ve known and admired, from near and afar, for Oalmost a half century. His is a remarkable life and career that defies reducing to a few words. Most recently, for more than three decades until his retirement in Janu- ary 2013, he served as a Democratic member of the U.S. Congress from the 4th Massachusetts District. As Chair- man of the House Financial Services Committee, he was at the center of activity in Washington from the start of the Great Recession throughout the mortgage foreclosure bailout crisis and the most extensive reform of the nation’s banking and financial services industry since the Great Depression. At this most trying time, Henry Paulson, Sec- retary of the Treasury in the administration of President George W. Bush, said he especially appreciated Barney Frank’s penchant for brokering good deals. “He is look- ing to get things done and make a difference”, Paulson wrote, “He focuses on areas of agreement and tries to build on those.”24 1980, he quickly became known for his quick wit, his Barney Frank was born and raised in Bayonne, New keen intelligence, his extraordinary work ethic, and his Jersey, the grandson of Polish and Irish immigrants. He passionate eloquence, for which the congressional staff graduated from Bayonne High School before attending and Washington press corps repeatedly recognized and Harvard College, did graduate work in government there, honored him. The breadth of his contributions while and served as chief assistant to Boston Mayor Kevin White in the Congress is, in a word, breath-taking. -

Congressman Barney Frank to Speak at National Constitution Center a Citizens’ Constitutional Conversation

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Denise Venuti Free Ashley Berke Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6636 215.409.6693 [email protected] [email protected] CONGRESSMAN BARNEY FRANK TO SPEAK AT NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER A CITIZENS’ CONSTITUTIONAL CONVERSATION PHILADELPHIA, PA (JANUARY 30, 2006) – Thirteen-term United States Congressman Barney Frank from Massachusetts will join the National Constitution Center on Wednesday, February 22, 2006 at 6:30 p.m. for a Citizens’ Constitutional Conversation. A prominent, provocative figure in the Democratic Party, Frank is outspoken on many human rights issues. Audience members will have the opportunity to listen to Frank share his constitutional expertise on issues such as the evolving Supreme Court, Congressional ethics issues and gay marriage. National Constitution Center President and CEO Richard Stengel will moderate. Citizens’ Constitutional Conversations are underwritten by The Citizens Bank Foundation. Admission is $12 for members, $15 for non-members and $6 for students and K-12 teachers. Advance reservations are required and can be made by calling 215.409.6700. Barney Frank was the first openly gay member of the U.S. Congress, where he has served since 1981. He currently serves as the senior Democrat on the Financial Services Committee and is also a member of the Homeland Security Committee. Before his work in the U.S. House of Representatives, Frank served as a Massachusetts State Representative and an assistant to the mayor of Boston. A graduate of Harvard University, he has also taught at several Boston area universities. -MORE- ADD ONE/BARNEY FRANK Located at 525 Arch Street on Philadelphia’s historic Independence Mall, the National Constitution Center is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to increasing public understanding of the U.S. -

October 2008 Layout

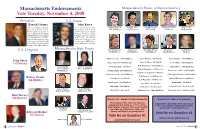

Massachusetts Endorsements Massachusetts House of Representatives Vote Tuesday, November 4, 2008 President U.S. Senate Barack Obama John Kerry First as a community organizer, Senator John Kerry earned the Jennifer Benson Geraldo Alicea Joseph Driscoll Barbara L’Italien Sara Peake then a State Senator, a U. S. Boston Carmen’s Union Lo- 37th Middlesex 6th Worcester 5th Norfolk 18th Essex 4th Barnstable Senator and now as the Demo- cal 589 endorsement with his cratic candidate for President, strong pro-worker, pro-union Barack Obama has been a fighter voting record for 24 years in for working women and men. the U.S. Senate. Senator Kerry Senator Obama supports workers joined with Local 589 to suc- rights, opposes privatization, will cessfully oppose MBTA priva- protect pensions and Local 589 tization and deserves our votes. is proud to endorse Barack Obama. Massachusetts State Senate U.S. Congress Danielle Gregoire Jim Arciero Mary Kate Hogan Jim Dwyer Lori Ehrlich 4th Middlesex 2nd Middlesex 3rd Middlesex 30th Middlesex 8th Essex Thomas Conroy - 13th Middlesex James Murphy - 4th Norfolk Kevin Murphy - 18th Middlesex John Olver 1st District James Cantwell - 4th Plymouth Marie St. Fleur - 5th Suffolk Corey Atkins - 14th Middlesex Pam Richardson - 6th Middlesex Ken Donnelly Jennifer Flanngan Devan Romanul - 1st Bristol Cheryl Rivera - 10th Hampden Union Member Worc. & Middlesex Harold Naughton - 12 Worcester 4th Middlesex Stephen Smith - 28th Middlesex Rosemary Sandlin - 3rd Hampden Linda Dean Campbell - 15th Essex Katherine Clark - 32nd Middlesex Christopher Donelan - 2nd Franklin John Fresolo - 16th Worcester Barney Frank Carlo Basile - 1st Suffolk Michael Rodrigues - 8th Bristol 4th District Paul Kujawski - 8th Worcester Paul Donato - 35th Middlesex Kevin Aguir - 7th Bristol Anne Gobi - 5th Worcester Mike Rush - 10th Suffolk Robert Rice - 2nd Worcester Mathew Patrick - 3rd Barnstable James Timilty Jamie Eldridge Bristol & Norfolk Middlesex & Worc.