Direct Interaction of Antifungal Azole-Derivatives with Calmodulin: a Possible Mechanism for Their Therapeutic Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jp Xvii the Japanese Pharmacopoeia

JP XVII THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA SEVENTEENTH EDITION Official from April 1, 2016 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the convenience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 64 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Law on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law No. 145, 1960), the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 65, 2011), which has been established as follows*, shall be applied on April 1, 2016. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``previ- ous Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as ``new Pharmacopoeia'')] and have been approved as of April 1, 2016 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as of March 31, 2016 as those exempted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Same Law (hereinafter referred to as ``drugs exempted from approval'')], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on September 30, 2017. -

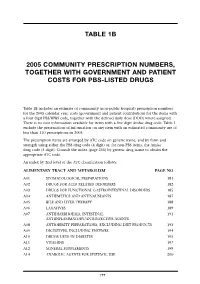

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

EUROPEAN PHARMACOPOEIA 10.2 Index 1. General Notices

EUROPEAN PHARMACOPOEIA 10.2 Index 1. General notices......................................................................... 3 2.2.66. Detection and measurement of radioactivity........... 119 2.1. Apparatus ............................................................................. 15 2.2.7. Optical rotation................................................................ 26 2.1.1. Droppers ........................................................................... 15 2.2.8. Viscosity ............................................................................ 27 2.1.2. Comparative table of porosity of sintered-glass filters.. 15 2.2.9. Capillary viscometer method ......................................... 27 2.1.3. Ultraviolet ray lamps for analytical purposes............... 15 2.3. Identification...................................................................... 129 2.1.4. Sieves ................................................................................. 16 2.3.1. Identification reactions of ions and functional 2.1.5. Tubes for comparative tests ............................................ 17 groups ...................................................................................... 129 2.1.6. Gas detector tubes............................................................ 17 2.3.2. Identification of fatty oils by thin-layer 2.2. Physical and physico-chemical methods.......................... 21 chromatography...................................................................... 132 2.2.1. Clarity and degree of opalescence of -

Ketoconazole and Posaconazole Selectively Target HK2 Expressing Glioblastoma Cells

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 15, 2018; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1854 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Ketoconazole and Posaconazole Selectively Target HK2 Expressing Glioblastoma Cells Sameer Agnihotri1*^, Sheila Mansouri2^, Kelly Burrell2, Mira Li2, Jeff Liu2, 3, Romina Nejad2, Sushil Kumar2, Shahrzad Jalali2, Sanjay K. Singh2, Alenoush Vartanian2, Eric Xueyu Chen4, Shirin Karimi2, Olivia Singh2, Severa Bunda2, Alireza Mansouri5, Kenneth D. Aldape2, Gelareh Zadeh2, 5* 1. Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 4401 Penn Ave. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15224, USA 2. MacFeeters-Hamilton Center for Neuro-Oncology Research, Princess Margaret Cancer Center, 101 College St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5G 1L7 3. Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3E1 4. Division of Medical Oncology and Haematology, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University of Toronto, Canada 5. Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MA, USA 6. Toronto Western Hospital, 4-439 West Wing, 399 Bathurst St., Toronto, ON M5T 2S8 Running title: Azoles inhibit HK2 and GBM growth ^ Equal contributing co-authors *Correspondence: Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD Associate Professor of Neurosurgery MacFeeters-Hamilton Center for Neuro-Oncology Research, Princess Margaret Cancer Center, 101 College St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5G 1L7 [email protected] Sameer Agnihotri, PhD Assistant Professor of Neurological Surgery Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Rangos Research Center, 7th Floor, Bay 15 530, 45th Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15201 [email protected] + The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. -

Drug Consumption at Wholesale Prices in 2017 - 2020

Page 1 Drug consumption at wholesale prices in 2017 - 2020 2020 2019 2018 2017 Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. ATC code Subgroup or chemical substance price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 321 590 7 309 580 7 300 278 7 295 060 8 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01AA Caries prophylactic agents 663 8 611 11 619 12 1 042 11 A01AA01 sodium fluoride 610 8 557 12 498 15 787 14 A01AA03 olaflur 53 1 54 1 50 1 48 1 A01AA51 sodium fluoride, combinations - - - - 71 1 206 1 A01AB Antiinfectives for local oral treatment 1 266 10 1 101 6 1 052 6 944 6 A01AB03 chlorhexidine 930 6 885 7 825 7 706 7 A01AB11 various 335 21 216 0 227 0 238 0 A01AB22 doxycycline - - 0 100 0 100 - - A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AC01 triamcinolone 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A01AD02 benzydamine 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 30 885 4 32 677 4 35 102 5 37 644 7 A02A ANTACIDS 3 681 1 3 565 1 3 357 1 3 385 1 A02AA Magnesium compounds 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AA04 magnesium hydroxide 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AD Combinations and complexes of aluminium, 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 calcium and magnesium compounds A02AD01 ordinary salt combinations 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 A02B DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND 27 205 5 29 112 4 31 746 5 34 258 8 -

Environmentally Classified Pharmaceuticals 2014-2015

2014-2015 ENVIRONMENTALLY CLASSIFIED PHARMACEUTICALS Stockholm County Council Contents Reducing Residues from Pharmaceuticals in Nature is Part Reducing Residues from Pharmaceuticals of the Environmental Work of in Nature is Part of the Environmental Work of Stockholm County Council ..................1 Stockholm County Council Impact of Pharmaceuticals on Contributing to the reduction of environmental the Environment .........................................................................2 risks from pharmaceuticals is an important part How the Substances are Classified ......................2 of the environmental work of Stockholm County How to Read the Table .................................................4 Council. According to the Environmental Challenge Substances which are Exempt 2016, the Council´s 2012-2016 Environmental from Classification ............................................................6 Programme, the Council is mandated to i.a. do The Precautionary Principle ......................................6 preventive environmental health work. This invol- Tables A Alimentary Tract and Metabolism............................7 ves fostering healthy inhabitants in an environ- ment with clean air and water. To reduce the most B Blood and Blood-Forming Organs ............................9 environmentally hazardous remains of medicinal C Cardiovascular System .................................................10 products in the natural surroundings is therefore D Dermatologicals ............................................................13 -

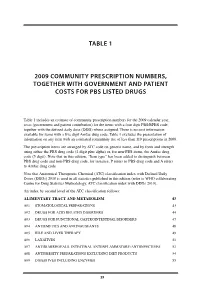

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES -

A Double-Blind Comparative Study of Sodium Sulfacetamide Lotion 10% Versus Selenium Sulfide Lotion 2.5% in the Treatment of Pityriasis (Tinea) Versicolor

THERAPEUTICS FOR THE CLINICIAN A Double-Blind Comparative Study of Sodium Sulfacetamide Lotion 10% Versus Selenium Sulfide Lotion 2.5% in the Treatment of Pityriasis (Tinea) Versicolor Cheryl A. Hull, MD; Sandra Marchese Johnson, MD Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor, which consists of To confirm clinical suspicion of pityriasis versi- hyperpigmented and hypopigmented scaly color, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation is patches, is often difficult to treat. A double-blind performed. Scale from the affected area is placed comparative study between once-a-day sodium on a glass slide, and 10% to 15% KOH is added sulfacetamide lotion and selenium sulfide lotion with or without dimethyl sulfoxide. A fungal stain, was undertaken. Both treatments were safe and such as chlorazol black E or Parker blue-black ink, efficacious. Selenium sulfide was statistically may be added to highlight hyphae and yeast cells. more efficacious (76.2% vs 47.8%, Pϭ.013). A confirmatory KOH preparation reveals short Cutis. 2004;73:425-429. stubby hyphae and yeast forms, either of which may predominate.1-3 Many treatment options for pityriasis versicolor ityriasis (tinea) versicolor is a superficial exist. Selenium sulfide shampoo is considered to be infection of the stratum corneum by the yeast the conventional first-line therapy at this time.4 P Malassezia furfur (also called Pityrosporum Most clinical trials in the treatment of pityriasis orbiculare),1 which is part of the normal cutaneous versicolor compare various experimental agents flora. Pityriasis versicolor is characterized by hyper- with selenium sulfide lotion 2.5%. However, sele- pigmented and hypopigmented scaly patches, pri- nium sulfide can be irritating to the skin, often marily on the trunk and proximal extremities. -

Topical Amphotericin B Semisolid Dosage Form for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Physicochemical Characterization, Ex Vivo Skin Permeation and Biological Activity

pharmaceutics Article Topical Amphotericin B Semisolid Dosage Form for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Physicochemical Characterization, Ex Vivo Skin Permeation and Biological Activity Diana Berenguer 1, Maria Magdalena Alcover 1 , Marcella Sessa 2, Lyda Halbaut 2 , Carme Guillén 1, Antoni Boix-Montañés 2 , Roser Fisa 1 , Ana Cristina Calpena-Campmany 2 , Cristina Riera 1 and Lilian Sosa 2,* 1 Department of Biology, Health and Environment, Laboratory of Parasitology, Faculty of Pharmacy and Food Sciences, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (M.M.A.); [email protected] (C.G.); rfi[email protected] (R.F.); [email protected] (C.R.) 2 Department of Pharmaceutical Technology and Physicochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy and Food Sciences, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (A.B.-M.); [email protected] (A.C.C.-C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-4024560 Received: 30 December 2019; Accepted: 10 February 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: Amphotericin B (AmB) is a potent antifungal successfully used intravenously to treat visceral leishmaniasis but depending on the Leishmania infecting species, it is not always recommended against cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). To address the need for alternative topical treatments of CL, the aim of this study was to elaborate and characterize an AmB gel. The physicochemical properties, stability, rheology and in vivo tolerance were assayed. Release and permeation studies were performed on nylon membranes and human skin, respectively. Toxicity was evaluated in macrophage and keratinocyte cell lines, and the activity against promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania infantum was studied. -

Amphotericin B/Bromochlorosalicylanilide 527

Amphotericin B/Bromochlorosalicylanilide 527 MUCOCUTANEOUS LEISHMANIASIS. Amphotericin B is used in mu- Pol.: AmBisome; Amphocil; Port.: Abelcet; AmBisome; Amphocil; Fungi- Preparations cocutaneous leishmaniasis unresponsive to antimonials. Suc- zone; Rus.: AmBisome (АмБизом); Amphoglucamin (Амфоглюкамин); S.Afr.: AmBisome; Fungizone; Singapore: Abelcet; AmBisome; Am- Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Part 3) cessful treatment with liposomal amphotericin B has been re- Cz.: Ecalta; Port.: Ecalta; UK: Ecalta; USA: Eraxis. 19 20 phocil†; Fungizone; Spain: Abelcet; AmBisome; Amphocil; Funganiline†; ported in immunocompetent and immunocompromised Fungizona; Swed.: Abelcet†; AmBisome; Fungizone; Switz.: Abelcet†; Am- patients. Bisome; Ampho-Moronal; Fungizone; Thai.: AmBisome†; Amphocil; Fung- 1. Gradoni L, et al. Treatment of Mediterranean visceral leishma- izone; Turk.: Abelcet; AmBisome; Fungizone; UK: Abelcet; AmBisome; niasis. Bull WHO 1995; 73: 191–7. Amphocil; Fungilin; Fungizone; USA: Abelcet; AmBisome; Amphotec; Fun- Bifonazole (BAN, USAN, rINN) gizone†; Venez.: Amphotec; Fungizone. 2. Syriopoulou V, et al. Two doses of a lipid formulation of am- Bay-h-4502; Bifonatsoli; Bifonazol; Bifonazolas; Bifonazolum. 1-(α- photericin B for the treatment of Mediterranean visceral leish- Multi-ingredient: Austria: Mysteclin; Braz.: Anfoterin†; Gino-Teracin; Biphenyl-4-ylbenzyl)imidazole. maniasis. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 560–6. Novasutin; Talsutin; Tericin AT; Tricocilin B; Vagiklin; Chile: Talseclin†; Fr.: 3. Davidson RN, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) in Amphocycline; Ger.: Mysteclin; Hong Kong: Tal su t in ; Indon.: Talsutin; Бифоназол Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis: a multi-centre trial. Q J Ital.: Anfocort; Malaysia: Talsutin†; Philipp.: Vagimycin; S.Afr.: Vagmycin; C H N = 310.4. Med 1994; 87: 75–81. Spain: Gine Heyden†; Sanicel; Trigon Topico; Venez.: Talsutin†. 22 18 2 4. -

Therapy of Skin, Hair and Nail Fungal Infections

Journal of Fungi Review Therapy of Skin, Hair and Nail Fungal Infections Roderick Hay Kings College London, London SE5 9RS, UK; [email protected] Received: 25 June 2018; Accepted: 10 August 2018; Published: 20 August 2018 Abstract: Treatment of superficial fungal infections has come a long way. This has, in part, been through the development and evaluation of new drugs. However, utilising new strategies, such as identifying variation between different species in responsiveness, e.g., in tinea capitis, as well as seeking better ways of ensuring adequate concentrations of drug in the skin or nail, and combining different treatment methods, have played equally important roles in ensuring steady improvements in the results of treatment. Yet there are still areas where we look for improvement, such as better remission and cure rates in fungal nail disease, and the development of effective community treatment programmes to address endemic scalp ringworm. Keywords: dermatophytes; cutaneous candidiasis; Malassezia infection; treatment; onychomycosis 1. Introduction Fungal infections of the skin and its adnexal structures, such as hair and nails, are common in all regions of the world. Yet over the last 40 years, there have been huge advances in the management of these conditions, starting from a time when most of the available therapies were simple antiseptics with some antifungal activity, to the present day where there is a large and growing array of specific antifungal antimicrobials. Although the course to modern treatment has not been without its problems, the complications, commonly encountered amongst antibacterials, particularly drug resistance, have not had a major impact on the currently used antifungals, with the possible exception of the superficial Candida infections, where azole resistance is well recognised. -

Antifungal Drug Repurposing

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific acultyF Articles All Faculty Scholarship 11-1-2020 Antifungal drug repurposing Jong H. Kim USDA ARS Western Regional Research Center (WRRC) Luisa W. Cheng USDA ARS Western Regional Research Center (WRRC) Kathleen L. Chan USDA ARS Western Regional Research Center (WRRC) Christina C. Tam USDA ARS Western Regional Research Center (WRRC) Noreen Mahoney USDA ARS Western Regional Research Center (WRRC) See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kim, J. H., Cheng, L., Chan, K. L., Tam, C. C., Mahoney, N., Friedman, M., Shilman, M. M., & Land, K. M. (2020). Antifungal drug repurposing. Antibiotics, 9(11), 1–29. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics9110812 https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/814 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific acultyF Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jong H. Kim, Luisa W. Cheng, Kathleen L. Chan, Christina C. Tam, Noreen Mahoney, Mendel Friedman, Mikhail Martchenko Shilman, and Kirkwood M. Land This article is available at Scholarly Commons: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/814 antibiotics Perspective Antifungal Drug Repurposing Jong H. Kim 1,* , Luisa W. Cheng 1, Kathleen