Matariki, Commodity Culture, and Multiple Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating Matariki As a Nation

Celebrating Matariki as a nation • Celebrating Matariki as a public holiday beginning in 2022, allowing time for the government and businesses to prepare and recover from the impact of COVID-19. Labour is proud of the way New Zealanders united against COVID 19. Our response has brought to light who we are as a country. When times get tough, we come together and we support each other. We are kind, and we are caring. As New Zealanders we are proud of who we are, what we stand for, the way we weave together different worlds and cultures to create our unique national identity. Te Ao Māori plays a large part in not just defining who we are as a nation, but sets us apart from the rest of the world. Te Ao Māori only belongs here in Aotearoa. Matariki, the Māori New Year, plays an intrinsic role in Māori culture. Over recent years has resurged as a time of celebration, not just for Māori but for our multicultural communities everywhere. Matariki is now a time we all come together for festivals, local events, balls and dinners to mark this important time of the year. Many New Zealanders already value and understand its importance, Māori have always acknowledged its meaning – so it is time, that as a country, we mark Matariki officially with a public holiday. It is day we can celebrate the Māori New year, but it is also a fitting time to come together and celebrate who we proudly are as New Zealanders. Why Matariki Acknowledging Māori New Year by marking its occurrence with a public holiday has been called for by both Māori and non-Māori New Zealanders. -

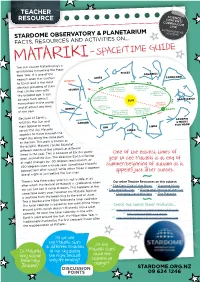

MATARIKI- SPACE/TIME GUIDE the Star Cluster Matariki Plays A

TEACHER SCIENCE RESOURCE CONTENT/ CURRICULUM LINK ASTRONOMICAL STARDOME OBSERVATORY & PLANETARIUM SYSTEMS FACTS, RESOURCES AND ACTIVITIES ON... MATARIKI- SPACE/TIME GUIDE The star cluster Matariki plays a pivotal role in marking the Māori PISCES New Year. It is one of the AQUARIUS ARIES CAPRICORN nearest open star clusters MATARIKI SEP A OCT UG to Earth, and is the most V Matariki rises early JU obvious grouping of stars O Matariki rises in the morning & is visible L TAURUS N middle of the night & until sunrise that can be seen with is visible until sunrise Matariki rises pre-dawn & is visible the unaided eye. It can until sunrise Matariki rises late C evening & is visible E N SAGITTARIUS be seen from almost until early morning SUN D U Matariki is J everywhere in the world, not visiable Matariki rises and at almost any time at dusk & is visible Matariki is visible near GEMINI until late EARTH Matariki is visible high the western horizon JA of the year. N in the sky at dusk & is at dusk & is visible Y for a short while MA visible in the evening FEB APR Because of Earth’s MAR SCORPIO rotation, the Sun and CANCER & MAUI’S FISH HOOK stars appear to move LEO LIBRA across the sky. Matariki VIRGO appears to move through the night sky along the same path as the Sun. This path is known as the ecliptic. Matariki can be found at different points of the ecliptic at different times in the year. This is because of Earth’s yearly One of the easiest times of orbit around the Sun. -

Roscommon School Whakapono Ki a Koe ~ Believe in Yourself NEWSLETTER 3 July 2017 Week 10, Term 2

Roscommon School Whakapono ki a koe ~ Believe in yourself NEWSLETTER 3 July 2017 Week 10, Term 2 2017 Annual Theme I wander/ wonder about our world... Kia ora, Talofa, Malo e lelei, Kia orana, Namaste, Bula vinaka, Fakalofa lahi atu, G’day, and Greetings to all our families. The end of the term is upon us. We are all feeling of school, that we can forget to keep you posted ready for a holiday. Teachers have been busy about what our core school business is all about: summing up the first half of the year writing their LEARNING. Mid Year Reports, and students have been pre- paring for our Student Learning/Led Conferenc- es (SLC’s) next week. We look forward to shar- MATARIKI ing some updates here in our newsletter and Some of our classes celebrated the beginning of also when we see you this week at our SLC’s. Matariki this week. The Juniors will be using this op- portunity to build on their unit around Planet Earth and Beyond (learning about the sun, moon, night JUST A FRIENDLY REMINDER... and day, etc). Others also visited the Stardome and FoNP attended a Matariki celebration per- Tomorrow Tuesday 4th July formance at Aotea on Friday. We thought we’d School will finish early share some information about Matariki and also at 12.30pm some of the work from our Juniors. For Student Learning/ Led Conferences Matariki (the Pleiades) Friday 7th July School will finish early at 2pm Last day of Term 2 Matariki is the Maori name for the cluster of KEEPING UP stars known as the Pleiades. -

Chinese New Year by Cherie Wu Photographs by Mark Coote

ChineseCChhihinhiinnneeesssee NewNNeewew YearYYeaYeeaearar Chinese New Year by Cherie Wu photographs by Mark Coote Shared reading There is an audio version of the text as an MP3 file at www.readytoread.tki.org.nz Shared reading provides students with opportunities to behave like readers and to engage in rich conversations Cross-curriculum links about texts that they are initially not able to read for Social sciences: (level 1, social studies) – Understand how themselves. It encourages enthusiasm for reading, builds the cultures of people in New Zealand are expressed in knowledge, strengthens comprehension, and fosters their daily lives. understanding of the features of a wide variety of texts (level 2, social studies) – Understand how cultural (including narrative, poetry, and non-fiction). practices reflect and express people’s customs, traditions, Shared reading involves multiple readings of a text, led by and values. the teacher, with increasing interaction and participation Related texts by students. After many shared reading sessions, students • Texts about cultural celebrations: Diwali, Matariki become increasingly independent in reading the small Breakfast (shared); White Sunday in Sāmoa books that accompany the big books. (Turquoise 2); Matariki (Gold 2) Overview • Stories with Chinese content: Let’s See Ling Lee This book follows Murphy and his family as they prepare (Blue 2); Two Tiger Tales (Purple 1); “Chang-O and the for and celebrate Chinese New Year. It describes significant Moon” (JJ 56); “The Race” (a play – SJ L2, May -

Thursday, March 19, 2020

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 ‘UNBELIEVABLE’ KIWIFRUIT HISTORIC CHANGE HARVEST SO FAR PAGE 3 FOR NZ’S ABORTION ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAWS PAGE 6 PAGES 23-26 INSIDE TODAY SHALL WE DANCE? Family bragging rights will be on the line when Gisborne brothers Campbell (left) and Alex Chrisp and sisters Pamela Hall (left) and Monica Williams go toe to toe at the Dancing for Life Ed charity event at the Farmers Air Showgrounds Park Event Centre fundraiser on June 20. The pairs chose rock and roll as their dance style and have been having a lot of fun learning the moves for the big event, which is raising money for the Life Education Trust. “I think we’ve got the rhythm and it’s for a great cause,” said Pamela. “If nothing else, it will give our families a laugh.” STORY ON PAGE 4 Picture by Chanellcrown Photography PANDEMIC COULD DELAY RATES RISE by Aaron van Delden Relief package announcement tomorrow Public advised to GISBORNE ratepayers are being asked • if they want the district council to lessen GOVERNMENT ministers will be in Gisborne here to announce a relief package for Covid- a 2020/21 rates hike by delaying the tomorrow to reveal details of a tailored 19-affected workers in the region. ‘shop normal’ wastewater treatment plant upgrade and economic relief package for Tairawhiti. The move comes on top of a national forgoing extra staff to process resource Economic Development Minister Phil relief package announced earlier this week. • More local events fall consent applications on time. -

Healthy Celebrations Ideas and Recipes for Early Learning Services

Healthy Celebrations Ideas and recipes for early learning services learnbyheart.org.nz 1 Contents Introduction 3 About us 5 Sample celebrations guideline 6 Celebrations – ideas and recipes 8 • Birthdays 8 • Chinese New Year 12 • Heart Day 16 • Easter 20 • Mother’s Day and Father’s Day 24 • Pacific Island Language Weeks 26 • Matariki 30 • Eid 34 • Diwali 38 • Christmas 42 • General tips and information 46 Photo: Vincent Ward 2 Introduction Celebrations are valued by early learning services as an opportunity to bring together children, families and the wider community. They are a chance to share each other’s milestones, culture and support whakawhanaungatanga – building relationships with others. Most importantly, celebrations can be fun and inclusive while also supporting your wider values as a service. The purpose of this guide is to provide practical ideas and recipes to help make healthy eating and physical activity an integrated part of your celebrations, so celebrations reflect your ongoing commitment to children’s health and wellbeing. Children can choke on food at any age but the risk is higher in children under 5 years. Refer to the Ministry of Health Guidelines to find out more. Search ‘food and choking' at health.govt.nz Consider the following when planning your celebrations Consistent healthy messaging Children learn from what they see and experience around them. Celebrations can be consistent with the messages you teach children about healthy eating and physical activity. This includes how adults role model healthy eating. Check that when your celebration involves food, there are healthy options available and foods are served in appropriate child-size portions. -

Wali Dad and the Gold Bracelet Level the Land of Five Rivers Level

Level Wali Dad and the Gold Bracelet 22 Level The Land of Five Rivers 24 Inquire to Learn! There are many ways in which Wali Dad and the Gold Bracelet/The Land of Five Rivers can be used as a base for Inquiry Learning. This is just one suggestion. Session 1 Using the Big Book, share-read Wali Dad and thankfulness, tolerance, trustworthiness, the Gold Bracelet, stopping at natural points for truthfulness, and understanding. Are some values discussion. Draw on the students’ prior knowledge more important than others? Why/why not? of money and savings; presents; kindness, bravery, and truthfulness; fairies/spirits and magic; and Fairies/Spirits and Magic: Introduce the term go-betweens/agents. peri and define it as a good spirit or fairy-like creature from the Punjabi culture. Brainstorm Possible Starter Questions for Discussion other traditional tales, including fairytales, that contain fairies who can perform magic e.g. Peter Money and Savings: What do people do with Pan, Sleeping Beauty, Pinocchio, and Cinderella. money they don’t need for everyday living? Discuss Encourage the children to share information on that people usually save their spare money. fairies/magical creatures from their cultures. Today, people use banks for their savings. Some people choose to give away some of their Go-Betweens/Agents: What do you do if you don’t spare money to other family members or to know how to do something? Lead a discussion on charities, or deserving causes. the role of go-betweens and agents, particularly as they apply to stories. A real-life example of a Presents: On what occasions do we normally give go-between the children may be familiar with is and receive presents? If someone gives you a present, a real-estate agent, who helps people buy and sell is it expected that you will give them a present in houses. -

Item 15 Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board Grant Round Two,2018/2019, Incl

Business Improvement Districts Application Summary OPBID1819-02 - 00003 Otara Business Association Project Title: Matariki Current Stage: Submitted Decision: Undecided Grant Round Two: Otara-Papatoetoe Decision Date: 21st May 2019 Contestable Fund for Business Amount Requested: $5,000 Improvement Districts 2018 Total Allocated: $0.00 Applicant: Otara Business Association Total to be paid: $0.00 User: Rana Judge - [email protected] Total Paid: $0.00 Organisation office address * Required 2/46 Fair Mall Otara Auckland 2023 Website and/or Facebook page www.otara.co.nz Primary contact person * Required Project/activity contact person (must be a different Rana Judge person from the admin contact and needs to be a Position held in organisation * signatory designated for the organisation or group. * Required Required Manager Amandeep Parmar Daytime phone number * Required Position held in organisation * Required 09 274 6401 Chairman Mobile Phone Number Daytime phone number (02) 7274 6401 Mobile phone number Email address * Required (02) 1056 7347 [email protected] Email address [email protected] What is the legal status of your Where is the project/activity taking place? * Required group/organisation? * Otara Town Centre and East Tamaki Road . Incorporated Society Project/Activity Title: Proposed start date * Required Matariki 29/06/2019 Please describe your project/activity Matariki, the Maori New Year, is rich with tradition, in three to four sentences * Discover the importance of Matariki, and explore ways that you can celebrate the Maori New Year with the family. There are quite numbers of Maori Population in Otara Some of them legends/heroes who will be Acknowledged will be Maori. -

120+ Days to Celebrate in 2020

+ 120 DAYS TO CELEBRATE IN 2020 JANUARY MAY SEPTEMBER January 1 New Years Day May 1 May Day September 3 Andy Griffiths’ birthday January 3 J.R.R Tolkien Day May 4 Star Wars Day September 8 International Literacy Day January 6 Epiphany/Three Kings Day May 4 Screen Free Week Septmber 11 Make Your Bed Day January 17 Kid Inventors’ Day May 5 Cinco de Mayo September 13 Roald Dahl’s birthday January 18 A A Milne’s birthday May 7 Michael Rosen’s birthday September 16 Julia Donaldson’s birthday January 20 Martin Luther King, Jr Day May 15 L Frank Baum’s birthday September 18 Rosh Hashanah January 25 Chinese New Year May 15 International Day of Families September 19 Talk Like a Pirate Day January 26 Australia Day May 26 Raina Telgemeier’s birthday September 21 International Day of Peace January 27 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s birthday September 22 World Rhino Day January 28 Jackson Pollock’s birthday JUNE September 25 Shel Silverstein’s birthday June 4 International Hug a Cat Day FEBRUARY June 5 World Environment Day OCTOBER February 5 World Nutella Day June 8 World Oceans Day October 2 World Smile Day February 6 Waitangi Day June 10 Maurice Sendak’s birthday October 4 World Animal Day February 11 Mo Willems’ birthday June 12 Anne Frank’s birthday October 5 World Teacher’s Day February 12 Judy Blume’s birthday June 14 International Bath Day October 8 R.L. Stine’s birthday February 14 Valentine’s Day June 20 World Refugee Day October 10 World Mental Health Day February 25 Pancake Day June 21 International Yoga Day October 21 Reptile Awareness Day -

Lectionary Year B 2020-21

! ! Copies'of'this'Lectionary+&+Calendar'are'available'from:' ! Administration!Division! Resource!Centre! Methodist!Church!of!New!Zealand! Presbyterian!Church!of! Te!Hāhi!Weteriana!O!Aotearoa! Aotearoa!/!New!Zealand! PO!Box!931! PO!Box!9049! Christchurch! Wellington! ! Price:'$2.00'(incl'GST)' LECTIONARY & CALENDAR 2020-2021 Copyright!©!1992!Consultation!on!Common!Texts.!! YEAR B – MARK Common%Lectionary%(Revised)%1992%used!by!permission.! Copyright!©!2020!Methodist!Faith!and!Order!Committee.! Short!extracts!may!be!made!from!this!publicationB! acknowledgement!of!source!would!be!appreciated.! ! Calendar'and'Lectionary' ! Introduction! ! ! Calendar' This!Calendar!shows!the!dates!of!the!church’s!festivals! ! in!the!current!liturgical!year.!It!also!shows!dates!of! other!important!national,!international!and!ecumenical! ! celebrations!and!days!of!remembrance.! ! Lectionary' The!Lectionary!is!a!method!by!which,!over!a!period!of! ! three!years,!much!of!the%Bible%is!read!aloud!in!Church.! ! Full!coverage!requires!Bible!readings!every!day!of!the! ! year.!This!Lectionary,!being!oriented!towards!worship,! ! includes!readings!for!every!Sunday!and!major!festivals! when!they!fall!during!the!week.!The!one!exception!to! ! this!is!Holy!Week,!which!is!given!in!full.! ! This!Lectionary!and!Calendar!follows!the%Common% ! Lectionary%Revised%(1992)%produced!by!the!ecumenical! liturgical!body!known!as!the!Consultation!on!Common! ! Texts!(CCT),!and!is!produced!by!permission!of!the! ! CCT!as!a!service!to!parishes!and!preachers.!Neither! ! the!MCNZ!nor!the!PCANZ!is!responsible!for!the! -

Henderson-Massey Local Board Meeting Held on 21/08/2018

Work Programme 2017/2018 Q4 Report ID Lead Activity Name Activity Description Timeframe Budget FY17/18 Activity RAG Q3 Commentary Q4 Commentary Dept/Unit or Source Status CCO Arts, Community and Events 2175 CS: ACE: Community Q1;Q2;Q3;Q4 LDI: Opex $72,000 Completed Green HM/2018/68 Advisory Response Fund - Discretionary fund to respond to No allocations. 5,000 to the Fair Food charity Henderson-Massey community issues as they arise 4,000 to Heart of Te Atatu South during the year Balance: $62,000 14,000 to the Central Park Henderson Business Association 5,000 to Waitakere Central Community 5,000 to Ranui Community Centre 15,000 to Waitakere Ethnic Board 4,000 to Ecomatters Environment Trust 5,000 to the West Auckland Historical Society 5,000 to Ranui Action Project Nil Balance 210 CS: ACE: Arts Pacifica Arts Centre Q1;Q2;Q3;Q4 ABS: Opex $148,807 Completed Green The Pacifica Mama's and Cultural Trust In Q4 the Pacifica Mama's Arts and Cultural Trust & Culture at Corban Estate - Administer funding agreement with attracted a total of 6,785 visitors to Corban attracted 9340 visitors. The trust delivered 137 ABS Pacifica Pacific Mamas Arts and Cultural Estate. The trust delivered 144 programmes programmes to 6471 participants, including Mamas Arts and Trust for Pacific cultural services, to 6,055 participants, and staged 30 workshops with the West Auckland I-Kiribati Cultural Trust activities and programmes including: performances to 15,670 attendees. 16 community and a series of ‘Staying Safe’ Operational Support - performing arts programmes delivered to Māori workshops in partnership with Age Concern and Grant - language and visual arts outcomes. -

Download This Guide As a Pdf

TEACHER’S GUIDE Every Month is a New Year written by Marilyn Singer, illustrated by Susan L. Roth About the Book SYNOPSIS Genre: Poetry *Reading Level: Grade 4 In many places around the globe, the new year starts on January 1. But not everywhere! Chinese New Year is celebrated Interest Level: Grades 1–8 in January or February. Iranians observe Nowruz in March. For Guided Reading Level: T Thai people, Songkran occurs in April. Ethiopians greet the new year at Enkutatash in September. All these diverse cultural, Accelerated Reader® Level/ regional, and religious observances, and many others, have Points: N/A deep-rooted traditions and treasured customs. Lexile™ Measure: N/A Acclaimed poet Marilyn Singer has created a lively poetry collection that highlights sixteen of these fascinating festivities, *Reading level based on the some well-known and some less familiar. Together with Susan Spache Readability Formula L. Roth’s captivating collage illustrations, the poems take Themes: New Year’s readers to the heart of these beloved holidays. Every month Celebrations, Cultural/ of the year, somewhere in the world people celebrate with joy Regional/Religious and good wishes for a happy new year. Traditions, Calendars, Global Perspective, Geography, Cultural Diversity, Poetry Teacher’s Guide copyright © 2018 LEE & LOW BOOKS. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to share and adapt for personal and educational use. For questions, comments, and/or more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Visit us online at leeandlow.com. 1 Every Month is a New Year BACKGROUND “No matter how they celebrate or on what date, people everywhere find a time to wish Author’s Introduction: “Happy New Year! All one another, ‘Happy New Year.’” around the world, people celebrate New Year’s Day beginning at midnight when December 31 Calendars: For millennia, civilizations have becomes January 1.