Hoi Polloi, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesuit Drama 2014 Winter Musical

Jesuit Drama 2014 Winter Musical 47th Anniversary Season The Beast Music by Alan Menken Lyrics by Howard Ashman & Tim Rice Book by Linda Woolverton Information Meeting for Performers &Technicians Black Box Theater Harris Center, 900 Gordon Lane Tuesday December 33,, 2013 4:00pm 2014 Winter Musical Staff Welcome to Jesuit Drama! DESIGN STAFF Mr. Chris Adamson, Design/Construction Ms. Rachel Malin, Costuming/Properties Mr. Brian O’Neill, Sound/Special Projects Mr. Spencer Price, Production Supervisor/Media/Technology Ms. Sally Slocum, Tech Direction/Lighting MANAGEMENT STAFF Mr. Earl Andrews, Assistant Principal for VPA Mr. David Bischoff, VPA Program Director/Chair Ms. Cindy Dunning, Beyond the Black Box Coordinator Mrs. Cathy Levering, Managing Direction/Patrons Ms. Calleen Wilcox, House Management/Hospitality REHEARSAL STAFF Sam Bassel ‘16, Assistant Stage Manager Taber Brown ’14, Student Rep Erin Cairns ’14, Student Rep Andrew Callens ‘14, Assistant Stage Manager/Light Intern Rev. Phil Ganir, S.J. Guest Vocal Coach Rev. Michael Gilson, S.J. Dramaturge Mr. Paul LeBoeuf, Chaplain Mrs. Cathy Levering, Co-Music Direction Ms. Pamela Kay Lourentzos, Dance/Choreography Reed Miller ’14, Assistant Stage Manager/Sound Intern Mr. Ed Trafton, Artistic Direction/Co-Music Direction/Musical Staging Ms. Gina Williams, Guest Acting Coach Bradley Winkleman ‘14, Production Stage Manager Jesuit Drama Student Centered… Process Oriented… In the Ignatian Tradition… 1200 Jacob Lane Carmichael, CA 95608 (916) 480-2179 jesuithighschool.org/drama [email protected] About the Show Beauty & The Beast (((1(111994994994)) In 1991, the animated feature Beauty and the Beast became the first "cartoon" to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. -

The Cage Dialogues: a Memoir William Anastasi

Anastasi William Dialogues Cage The Foundation Slought Memoir / Conceptual Art / Contemporary Music US/CAN $25.00 The Cage Dialogues: A Memoir William Anastasi Cover: William Anastasi, Portrait of John Cage, pencil on paper, 1986 The Cage Dialogues: A Memoir William Anastasi Edited by Aaron Levy Philadelphia: Slought Books Contemporary Artist Series, No. 6 © 2011 William Anastasi, John Cage, Slought Foundation All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from either the author or Slought Books, a division of Slought Foundation. No part may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. This publication was made possible in part through the generous financial support of the Evermore Foundation and the Society of Friends of the Slought Foundation. Printed in Canada on acid-free paper by Coach House Books, Ltd. Set in 11pt Arial Narrow. For more information, http://slought.org/books/ “The idiots! They were making fun of you...” John Cage Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anastasi, William, 1933- The Cage dialogues : a memoir / by William Anastasi ; edited by Aaron Levy. p. cm. -- (Contemporary artist series ; no. 6) ISBN 978-1-936994-01-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cage, John. 2. Composers--United States--Biography. 3. Artists--United States-- Biography. I. Levy, Aaron, 1977- II. Title. ML410.C24A84 2011 780.92--dc22 [B] 2011016945 Caged Chance 1 William Anastasi You Are 79 John Cage and William Anastasi Selected Works, 1950-2007 101 John Cage and William Anastasi John Cage, R/1/2 [80] (pencil on paper), 1985 Caged Chance William Anastasi Now I go alone, my disciples, You, too, go now alone.. -

Musical Audition Tips

Centerstage Academy presents June 27-28, 2014 Disney’s Beauty and the Beast Audition Information We are excited about our upcoming production of Disney's Beauty and the Beast! Prior to auditions, you should receive an audition packet with the following materials: - Audition Information - Audition Form - Guidelines & Contract - Character Breakdown - Audition Sides - Biography Questionnaire - Costume Measurement Form - Program Ad Form - Audition Cheat Sheet - Vocal Demo CD When Are Auditions? Auditions will be held Saturday, January 18 between 9:00am and 6:00pm by appointment only. Callbacks may be scheduled for Sunday, January 19 between 2:00-5:00pm. Overflow appointments will be arranged as needed. Please schedule your audition time through the studio office at (757) 890-0175. Here are a few things to remember as you prepare for the audition. What's Different About This Production? We are planning for this production to be a large-scale event that gives our theatre students a more "professional" stage experience. We are in the process of renting the James-York Playhouse (200 Hubbard Lane, Wmbg) for our mainstage performances. This 300 seat theatre is newly constructed, with graduated seating for increased visibility and state-of-the-art lighting and sound. We are also challenging our students with the full-scale, original Broadway version of this classic musical (not the junior or high school edition). We make theatre education a priority with all of our shows, but this will certainly provide everyone--beginners AND veterans--with the opportunity for personal growth and artistic excellence! About the Original Broadway Version Step into the enchanted world of Broadway's modern classic! Based on the Academy-Award winning animated feature, the stage version includes all of the wonderful songs written by Alan Menken and the late Howard Ashman, along with new songs by Mr. -

Sample Poem Book

The Lord is My Shepherd; I shall not Our Father which art in want. He maketh me to lie down in green heaven, Hallowed be thy I’d like the memory of me pastures; He leadeth me beside the still name. Thy kingdom come. To be a happy one, waters. He restoreth my soul. He leadeth I’d like to leave an afterglow me in the path of righteousness for His Thy will be done in earth, as it Of smiles when day is done. name’s sake. Yea, though I walk through is in heaven. Give us this day I’d like to leave an echo the valley of the shadow of death, I will Whispering softly down the ways, fear no evil; for Thou art with me; Thy our daily bread. And forgive Of happy times and laughing times rod and Thy staff they comfort me. Thou us our debts, as we forgive And bright and sunny days. preparest a table before me in the our debtors. And lead us not I’d like the tears of those who grieve presence of mine enemies. Thou To dry before the sun anointest my head with oil; my cup into temptation, but deliver us Of happy memories that I leave behind, runneth over. Surely goodness and from evil: For Thine is the When the day is done. mercy shall follow me all the days of my life; and I will dwell in the house of the kingdom, and the power, and -Helen Lowrie Marshall Lord forever. the glory, for ever. -

Contemporary IdiomsTM Voice Level 5

Contemporary IdiomsTM Voice Level 5 Length of examination: 25 minutes Examination Fee: Please consult our website for the schedule of fees: www.conservatorycanada.ca Corequisite: Successful completion of the Theory 1 written examination is required for the awarding of the Level 5 certificate. REQUIREMENTS & MARKING Requirements Total Marks Piece 1 12 Repertoire Piece 2 12 4 pieces of contrasting styles Piece 3 12 Piece 4 12 Technique Listed exercises 16 Sight Reading Rhythm (3) Singing (7) 10 Aural Tests Sing back (4) Chords (3) Intervals (3) 10 Improvisation Improv Exercise or Own Choice Piece 8 Background Information 8 Total Possible Marks 100 *One bonus mark will be awarded for including a repertoire piece by a Canadian composer CONSERVATORY CANADA ™ Level 5 July 2020 1 REPERTOIRE ● Candidates are required to perform FOUR pieces from the Repertoire List, contrasting in key, tempo, mood and subject. Your choices must include at least two different composers. All pieces must be sung from memory and may be transposed to suit the compass of the candidate's voice. ● One of the repertoire pieces may be chosen from any level higher. ● The Repertoire List is updated regularly to include newer music, and is available for download on the CI Voice page. ● Due to time and space constraints, Musical Theatre selections may not be performed with elaborate choreography, costumes, props, or dance breaks. ● The use of a microphone is optional at this level, and must be provided by the student, along with appropriate sound equipment (speaker, amplifier) if used. ● Repertoire that is currently not on our lists can be used as Repertoire pieces with prior approval. -

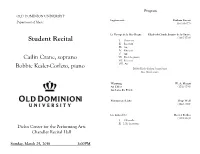

Student Recital I

Program OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Lagrime mie Barbara Strozzi Department of Music (1619-1677) Le Passage de la Mer Rogue Elizabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729) Student Recital I. Overture II. Récitatif III. Air IV. Récitatif V. Air Cailin Crane, soprano VI. Buit de guerre VII. Récitatif VIII. Air Bobbie Kesler-Corleto, piano Bobbie Kesler-Corleto, harpsichord Rees Ward, violin Warnung W. A. Mozart An Chloë (1756-1791) Als Luise die Briefe Nimmersate Liebe Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) Les nuits d’été Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) I. Villanelle II. L’ile inconnue Diehn Center for the Performing Arts Chandler Recital Hall Sunday, March 25, 2018 3:00PM Lagrime mie Lagrime mie, à che vi trattenete, Tears of mine, what holds you back. Perché non isfogate il dolore, Why don’t you give vent to the fierce pain Chi me toglie’l respiro e opprime il core? That takes away my breath and weighs on my A Cycle of Five Kid Songs Leonard Bernstein heart? (1918-1990) I. My Name is Barbara Lidia, che tant’ adoro, Lidia, whom I adore so much. Perché un guardo pietoso, Because of a pitying glance, II. Jupiter Has Seven Moons ahimè, mi donò, alas, that she gave me, III. I Hate Music! Il paterno rigor l’impriogginò. Paternal severity has imprisoned her. IV. A Big Indian and a Little Indian Tra due mura rinchiusa Locked up between two walls, V. I’m a Person Too Stà la bella innoncente, Remains innocent beauty, Dove guinger non può raggio di sole, Where no ray of sun can reach, E quel che più mi duole And what most pains me and increases my Ed accresc’il mio mal, tormenti e pene, discomfort, torments, and anguish, A Change in Me Alan Menken (b. -

Toni Braxton Download Album Music Love, Marriage & Divorce

toni braxton download album music Love, Marriage & Divorce. On Love, Marriage & Divorce, Toni Braxton and Babyface, creative partners going back to the early '90s, rekindle their musical relationship. Both endured broken marriages, and presumably it's those experiences that inform the material here -- a succinct collection of 11 songs, eight of which are duets. The emphasis is on divorce, indicated from the very beginning on "Roller Coaster," where Babyface enters with "Today I got so mad at you, it's like I couldn't control myself." The set finishes with the bittersweet "The D Word," seemingly a Sade homage, in which Babyface confesses "You still own my heart, forever and ever and ever." Moments that deviate from issues of romantic strife are few. The duo don't seem nearly as connected to them. "Sweat," a slinking groove, is like the "Love During War" to Robin Thicke's "Love After War," while "Heart Attack," near the album's end, is a retro-disco move that seems more like a throw-in than a crucial part of the album. The sequence of songs plays out like scenes on shuffle. Either that, or the relationship is extremely up and down; the singers sometimes sound as if they are addressing ex-lovers from other relationships. "Reunited" is a blissful ballad, but it's followed by the embittered "I'd Rather Be Broke," where Braxton asserts, "Just because your money's strong don't mean you can do the things that you do." Babyface is civil and clear-headed on "I Hope That You're Okay," claiming he "can't go through the motions anymore," but Braxton follows with a solo spotlight, "I Wish," that seems drawn from a different situation: "I hope she creeps on you with somebody who is 22/I swear to God, I'm gonna be laughing at you every day." As a narrative, the album can be hard to follow, but it's not as if breakups have a simple arc with a steady, unwavering decline. -

Btaurv AND't'he Btl-Sr MAURICE MAURICE MAURICE MAURICE ANDI

86 Btaurv AND't'HE Btl-sr SCENE FIVE: EXTERIOR BELLE'S HOUSE lil (Belle and Maurice enter.) BELLE We're finally home. Rest here. MAURICE I don't know what happened. The last thing I remember I was falling. '. BELLE You were in the woods, Papa. I thought I'd never find you".. MAURICE But the Beast? How did you escaPe? BELLE I didn't escape. He let me go. MAURICE He let you go? That terrible beast? BELLE He's not terrible. In the beginning I was so frightened; I thought it was the end of everything...But somehow. .things changed. MAURICE How? #76n - A Cltnttge In IVIe Balla BELLE I don't know but I see him differently now. (She looks around) It's funny...when I look around...I see the whole world differently' THERE'S BEEN A CHANGE IN ME A KIND OF MOVING ON THOUGH WHAT I USED TO BE I STILL DEPEND UPON FOR NOW I REALIZE THAT GOOD CAN COME FROM BAD THAT MAY NOT MAKE ME WISE BUT OH. IT MAKES ME GLAD ANDI _ I NEVER THOUGHT I'D LEAVE BEHIND MY CHILDHOOD DREAMS BUT I DON'T MIND Bneu rY aND THE Brt sr 87 - (BELLE) FOR NOW I LOVE THE WORLD I SEE NO CHANGE OF HEART A CHANGE IN ME FOR IN MY DARK DESPAIR I SLOWLY UNDERSTOOD MY PERFECT WORLD OUT THERE HAD DISAPPEARED FOR GOOD BUT IN IT'S PLACE I FEEL A TRUER LIFE BECIN AND IT'S SO GOOD AND REAL IT MUST COME FROM WITHIN ANDI _ I NEVER THOUGHT I'D LEAVE BEHIND MY CHILDHOOD DREAMS BUT I DON'T MIND rM WHERE AND WHO I WANT TO BE NO CHANGE OF HEART A CHANGE IN ME NO CHANGE OF HEART A CHANGE IN ME (Monsieur D'Arque enters with a mob) MONSIEUR D'ARQUE Bclla Good aftemoon. -

Score Alfred Music Publishing Co. Finn

Title: 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, The - score Author: Finn, William Publisher: Alfred Music Publishing Co. 2006 Description: Score for the musical. Title: 42nd Street - vocal selections Author: Warren, Harry Dubin, Al Publisher: Warner Bros. Publications 1980 Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: About a Quarter to Nine Dames Forty-Second Street Getting Out Of Town Go Into Your Dance The Gold Digger's Song (We're In The Money) I Know Now Lullaby of Broadway Shadow Waltz Shuffle Off To Buffalo There's a Sunny Side to Every Situation Young and Healthy You're Getting To Be a Habit With Me Title: 9 to 5 - vocal selections The musical Author: Parton, Dolly Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: Nine to Five Around Here Here for You I Just Might Backwoods Barbie Heart to Hart Shine Like the Sun One of the Boys 5 to 9 Change It Let Love Grow Get Out and Stay Out Title: Addams Family - vocal selections, The Author: Lippa, Andrew Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation 2010 Description: Vocal selections from the musical. includes: When You're an Addams Pulled One Normal Night Morticia What If Waiting Just Around the Corner The Moon and Me Happy / Sad Crazier than You Let's Not Talk About Anything Else but Love In the Arms Live Before We Die The Addams Family Theme Title: Ain't Misbehavin' - vocal selections Author: Henderson, Luther Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: Ain't Misbehavin (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue (Get Some) Cash For Your Trash Handful of Keys Honeysuckle Rose How Ya Baby I Can't Give You Anything But Love It's a Sin To Tell A Lie I've Got A Felling I'm Falling The Jitterbug Waltz The Joint is Jumping Keepin' Out of Mischief Now The Ladies Who Sing With the Band Looking' Good But Feelin' Bad Lounging at the Waldorf Mean to Me Off-Time Squeeze Me 'Tain't Nobody's Biz-ness If I Do Title: Aladdin and Out - opera A comic opera in three acts Author: Edmonds, Fred Hewitt, Thomas J. -

Originally Produced by Disney Theatrical Productions Music By

Originally Produced by Disney Theatrical Productions Music by ALAN MENKEN • Lyrics by HOWARD ASHMAN & TIM RICE • Book by LINDA WOOLVERTON Originally Directed by Rob Roth Director's Note Be Our Guest! I can't possibly thank the amazing cast and crew enough for the incredible amount of work they’ve done for this musical. None of this would have come together without their dedication and passion for theatre. We hope you’ll thoroughly enough yourself. I have held the belief for a very long time that Disney’s adaptation of Beauty and the Beast is a textbook example of a perfect animated movie. There’s a reason it was nominated for Best Picture. Its characters, the pacing of events, the themes and of course, the music, all fit together so well. It’s the timeless, magical tale that teaches children not to judge a book by its cover. As I approached bringing this story to life on the stage, I came to realize not just how deeply that message runs, but how many more lessons we can derive from this content aimed towards a younger demographic. This is what surprised me the most: the fact that this “Kids’ Musical” has so much to offer and teach us that we as adults are so quick to forget. There are simple morals, to be sure, such as the value of being kind, seeing the best in other people, and that uniqueness is to be celebrated… all things we should always try to keep in mind. You may think that these are obvious lessons, and I hope you do, but we as a society have reached a point where they cannot be stated enough. -

Visual Song Book

House of Fellowship Song Book 1 6 I Believe God The Water Way Key of A Key of F I believe God! I believe God! Long ago the maids drew water Ask what you will and it shall be done; In the evening time, they say Trust and obey, believe Him and say: One day Isaac sent his servant I believe, I believe God. To stop Rebekah on her way "My master sent me here to tell thee; And if you want salvation now See these jewels rich and rare; And the Holy Ghost and power, Would'st thou not his lovely bride be Just trust and obey, In that country over there?" Believe Him and say: I believe, I believe God. CHORUS It shall be light in the evening time, 2 The path to glory you will surely find; Reach Out, Touch The Lord Thru the water way, It is the light today, Key of F Buried in the precious Name of Jesus. Young and old, repent of all your sin, Reach out and touch the Lord The Holy Ghost will surely enter in; As He goes by, The evening Light has come, You'll find He's not too busy, It is a fact that God and Christ are one. To hear your heart's cry; He's passing by this moment, So, God's servants come to tell you Your needs to supply, Of a Bridegroom in the sky Reach out and touch the Lord Looking for a holy people As He goes by. To be his bride soon, by and by He sends to us refreshing water 3 In this wondrous latter day Feeling So Much Better They who really will be raptured Key of F Must go thru the water way Feeling so much better Are you on your way to ruin Talking about this good old Way, Cumbered with a load of care Feeling so much better See the quick work God is doing Talking about the Lord; That so his glory you may share Let's go on, let's go on At last the faith he once delivered Talking about this good old Way, To the saints, is ours today Let's go on, let's go on To get in the church triumphant Talking about the Lord. -

Beauty and the Beast | Running Order

Beauty and the Beast | Running Order ACT 1 Scene Pages Setting Scene/Songs Characters 0.1a p. 1 #1 - Overture (instrumental) 0.1b p. 1-2 Castle Doorway DIALOGUE #1a - Prologue Young Prince, Enchantress, Prologue Dancers 1.1a p. 2-8 Village SONG #2 - Belle Belle, Villagers, Baker, Bookseller, LeFou, Gaston, Silly Girls 1.1b p. 9-11 Outside Belle's House DIALOGUE #2a - Belle Playoff / Gaston and Belle Belle, Gaston, LeFou DIALOGUE - Maurice and Belle 1.1c p. 11-15 Outside Belle's House SONG #3 - No Matter What Belle, Maurice DIALOGUE - Maurice leaves for the Faire SONG #3a - No Matter What Reprise 1.2a p. 15-16 The Forest Maurice, Wolves, Gargoyles DIALOGUE #4 - Wolf Chase #1 1.3a p. 16-18 Castle Interior DIALOGUE - Maurice in the Castle Maurice, Lumiere, Cogsworth 1.3b p. 18-20 Castle Interior DIALOGUE - Maurice meets the Enchanted Objects Babette, Maurice, Cogsworth, Mrs. Potts, Chip, Lumiere 1.3c p. 20-21 Castle Interior DIALOGUE #4a - Maurice & the Beast Chip, Lumiere, Cogsworth, Maurice, Beast, Mrs. Potts 1.4a p. 22-23 Outside Belle's House DIALOGUE - Silly Girls and Gaston Silly Girls, Gaston DIALOGUE #4b - Gaston's Crossover / Gaston proposes 1.4b p. 23-25 Outside Belle's House Gaston, Belle SONG #5 - Me 1.4c p. 26 Outside Belle's House DIALOGUE - Silly Girls after Me Silly Girls, Gaston 1.4d p. 26 Outside Belle's House SONG #6 - Belle Reprise Belle 1.4e p. 26-27 Outside Belle's House DIALOGUE - Belle asks LeFou about the scarf LeFou, Belle 1.5a p.