Infotainment on Russian TV As a Tool of Desacralization of Soviet Myths and Creation of a Myth About the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation Performance Review of Kazakhstan

UNECE UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE Innovationn Innovation Performance Performance o I n i n o v Review a t i o Reviewt The Innovation Performance Review contains the n P e findings of a participatory policy advisory service r f undertaken at the request of the national authorities. o rm It considers possible policy actions aimed at a a stimulating innovation activity in the country, n c enhancing its innovation capacity and improving the e R efficiency of the national innovation system. e v i e w This publication is part of an ongoing series - K a highlighting some of the results of the UNECE v z Subprogramme on Economic Cooperation and a k Integration. The objective of the Subprogramme is to h s t promote a policy, financial and regulatory a environment conducive to economic growth, n knowledge-based development and higher o competitiveness in the UNECE region. n UNITED NA KAZAKHSTAN n TIONS I UNITED NATIONS United Nations Economic Commission for Europe INNOVATION PERFORMANCE REVIEW OF KAZAKHSTAN UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2012 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This volume is issued in English and Russian only. ECE/CECI/14 Copyright © United Nations, 2012 All right reserved Printed at United Nations, Geneva (Switzerland) UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS iii FOREWORD The Innovation Performance Review of Kazakhstan continues the series of national assessments of innovation policies initiated by the pilot Innovation Performance Review of Belarus. -

Telecoms & Media 2021

Telecoms & Media 2021 Telecoms Telecoms & Media 2021 Contributing editors Alexander Brown and David Trapp © Law Business Research 2021 Publisher Tom Barnes [email protected] Subscriptions Claire Bagnall Telecoms & Media [email protected] Senior business development manager Adam Sargent 2021 [email protected] Published by Law Business Research Ltd Contributing editors Meridian House, 34-35 Farringdon Street London, EC4A 4HL, UK Alexander Brown and David Trapp The information provided in this publication Simmons & Simmons LLP is general and may not apply in a specific situation. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. This information is not intended to create, nor does receipt of it constitute, a lawyer– Lexology Getting The Deal Through is delighted to publish the 22nd edition of Telecoms & Media, client relationship. The publishers and which is available in print and online at www.lexology.com/gtdt. authors accept no responsibility for any Lexology Getting The Deal Through provides international expert analysis in key areas of acts or omissions contained herein. The law, practice and regulation for corporate counsel, cross-border legal practitioners, and company information provided was verified between directors and officers. May and June 2021. Be advised that this is Throughout this edition, and following the unique Lexology Getting The Deal Through format, a developing area. the same key questions are answered by leading practitioners in each of the jurisdictions featured. Lexology Getting The Deal Through titles are published annually in print. Please ensure you © Law Business Research Ltd 2021 are referring to the latest edition or to the online version at www.lexology.com/gtdt. -

I. ANNEX – Country Reports

I. ANNEX – Country Reports 97 State of Affairs of Science, Technology and Innovation Policies 97 I.1 Country Report Armenia in cooperation and coordination with other concerned ministries and organisations. In order to improve policy-making and promote the coordination in the field of S&T, in October 2007 the government decided to establish the State Commit- tee of Science empowered to carry out integrated S&T policy in the country. This structure is answerable to the Ministry of Education and Science, but with wider power of independent activity. The Committee is also responsible for the development and implementation of research programmes in the country through three main I.1.1 Current State of S&T & Major financing mechanisms: thematic (project based) financ- Policy Challenges ing, basic financing and special purpose projects73. The law on the National Academy of Sciences of Arme- I.1.1.1 S&T Indicators nia (NAS RA) was adopted by Parliament on 14 April, 2011, which assigned to it the status of highest self- TABLE 5: S&T LANDSCAPE 201072 governing state organisation and empowered it to coor- dinate and carry out basic and applied research directed R&D Number of Number of to the creation of a knowledge-based economy, and Expenditure research researchers the social and cultural development of the country. This as % of GDP organisations Law gave more power to the Academy and its research institutes in carrying out business activities towards the 0.27 81 5,460 commercialisation of R&D outcomes and the creation of spin-offs. I.1.1.2 Research Structure and Policy In May 2010, the Government adopted the Strategy A pressing challenge for Armenia is the reformation on Development of Science in Armenia, which outlined of its S&T and innovation system in accordance with the state policy towards the development of science the requirements of the market economy and needs of from 2011 to 2020. -

The Economic Adjustment and Polarisation of Russia's Cities

Uneven urban resilience: the economic adjustment and polarisation of Russia's cities Oleg Golubchikov, Cardiff University1 Alla Makhrova, Moscow State University Anna Badyina, University of Southampton Isolde Brade, Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography Published as: Golubchikov, O., Makhrova, A., Badyina, A. and Brade, I. (2015). Uneven urban resilience: the economic adjustment and polarization of Russia's cities. In: Lang, T. et al. (eds.) Understanding Geographies of Polarization and Peripheralization: Perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 270-284. Introduction The multidimensional processes of transition to a market economy have produced a radical rupture to the previous development of Russian cities. Many factors driving urban change under the Soviet system, both of ideological and material nature, have lost their legitimacy or significance under the capitalist regime of accumulation and regulation. Thus, no longer perceived as a purpose-built machine for a meaningful evolution to a fair and egalitarian communist society as before, each city has been exposed to the ideology of the free market and pushed to acquire a new niche in the nexus of global and local capitalist flows. Not all cities equally succeeded in this endeavour. Indeed, already under the conditions of general economic disorganisation and harsh economic downturn introduced by the poorly performed neoliberal reforms of the early 1990s, different urban regions started demonstrating divergent trajectories of their economic performance, including severe marginalisation and peripheralisation by some and more successful adaptation by others. Those processes of initial spatial differentiation have proven to become self-perpetuating even under the conditions of ‘restorative’ growth experienced in Russia between 1998 and 2008, as well as the ensuring period of more bumpy economic growth. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Television in Russia Is the Concept of PSB Relevant?

Television in Russia Is the Concept of PSB Relevant? Elena Vartanova & Yassen N. Zassoursky In the traditional Western discourse on commercial and public service broad- casting, little attention was given to the state TV model which was present in many countries of the ‘Socialist’ block, and in many Asian states as well. Strictly speaking, public service broadcasting [PSB] is not a common con- cept shared and implemented by different countries in a similar way, but rather a continuum that implies different modes of interaction between the society, audience, state, and social institutions. In many European countries – France, Germany, Netherlands, Finland, Spain, – PSB practices indicate varying degrees of control and interference from political forces, governments and state agencies (Weymouth and Lamizet, 1996, Euromedia Research Group, 1997). The model of Western European PSB provides clear evidence that the state as a social agent is not an entirely antagonistic force to public service. On the contrary, “some forms of accountability to (political representatives of) the public, other than through market forces”, was traditionally considered a key public service element (McQuail & Siune, 1998: 24). This has led to the acceptance of some forms of content regulation embodying positive and negative criteria which, in turn, were shaped by the need to serve the pub- lic interest more than commercial, political or consumerist interests of soci- ety and audience. In Western Europe, there were fierce tensions between the goals set by ‘society’ in relation to the public interest and demands of the audience as consumers (McQuail, 2000:157). Dissimilar to this, post-Socialist societies experienced another tension paradigm. -

Television Across Europe

media-incovers-0902.qxp 9/3/2005 12:44 PM Page 4 OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM NETWORK MEDIA PROGRAM ALBANIA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA Television CROATIA across Europe: CZECH REPUBLIC ESTONIA FRANCE regulation, policy GERMANY HUNGARY and independence ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA Summary POLAND REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA ROMANIA SERBIA SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA TURKEY UNITED KINGDOM Monitoring Reports 2005 Published by OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary 400 West 59th Street New York, NY 10019 USA © OSI/EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program, 2005 All rights reserved. TM and Copyright © 2005 Open Society Institute EU MONITORING AND ADVOCACY PROGRAM Október 6. u. 12. H-1051 Budapest Hungary Website <www.eumap.org> ISBN: 1-891385-35-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. A CIP catalog record for this book is available upon request. Copies of the book can be ordered from the EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program <[email protected]> Printed in Gyoma, Hungary, 2005 Design & Layout by Q.E.D. Publishing TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................ 5 Preface ........................................................................... 9 Foreword ..................................................................... 11 Overview ..................................................................... 13 Albania ............................................................... 185 Bosnia and Herzegovina ...................................... 193 -

Xfinity Tv11

Services & Pricing Effective July 1, 2020 1-800-xfinity | xfinity.com Danville & Springfield Areas: BALL TWP, CAYUGA IN, CHAMPAIGN COUNTY, CHRISMAN, CURRAN TWP, DANVILLE, EUGENE IN, FAIRMOUNT, FITHIAN, GARDNER TWP, GRANDVIEW, HOMER, INDIANOLA, JEROME, LELAND GROVE, MUNCIE, OAKWOOD, OGDEN, OLIVET, PHILO, RIDGE FARM, ROCHESTER, Portions of SANGAMON COUNTY (ROCHESTER TWP), SIDNEY, SOUTHERN VIEW, SPRINGFIELD, ST JOSEPH TWP, Portions of VERMILLION COUNTY, WOODSIDE TWP 11 Brazilian 4 Pack Includes TV Globo, PFC, Band Internacional and Record TV $34.99 XFINITY TV Mandarin 2 Pack Includes Phoenix Info News and Phoenix North America $6.99 Mandarin 4 Pack Includes CTI Zhong Tian, CCTV4, Phoenix Info News and 16 Limited Basic $23.95 Phoenix North America $19.99 Basic Includes Limited Basic, Streampix, HD Programming and 20 hours Filipino 2 Pack Includes GMA Pinoy w/ GMA Video On Demand and GMA DVR Service $30.00 Life $14.99 Extra17 Includes Limited Basic, Sports & News, Kids & Family, Filipino 3 Pack Includes GMA Pinoy w/ GMA Video On Demand, GMA Life Entertainment, Streampix, HD Programming and 20 hours DVR Service. $70.00 and TFC $22.99 Preferred Includes Extra plus additional digital channels $90.00 TV5MONDE: French With Cinema On Demand $9.99 Digital Starter18 Includes Limited Basic, additional digital channels, TV DW Deutsche +: German $9.99 Box and remote for primary outlet, access to Pay-Per-View and On Demand Antenna: Greek $14.99 programming and Music Choice $69.95 The Israeli Network $19.99 19 Sports & News Includes 18 sports and news channels -

Russian Pay TV and SVOD Is Cord-Cutting

Russian Pay TV and SVOD Is Cord-cutting Really Happening? Russian Pay TV and SVOD: Is Cord-cutting Really Happening? European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2019 Director of Publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial Supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Market Information European Audiovisual Observatory Chief Editor Dmitry Kolesov, Head of TV and Content Department, J`son & Partners Consulting Authors Dmitry Kolesov, Head of TV and Content Department Anna Kuz, Consultant of TV and Content Department J`son & Partners Consulting Press and Public Relations Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] http://www.obs.coe.int Please quote this publication as D. Kolesov, A. Kuz, Russian Pay TV and SVOD: Is Cord-cutting Really Happening?, European Audiovisual Observatory, 2019 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, September 2019 Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. Russian Pay TV and SVOD Is Cord-cutting Really Happening? Dmitry Kolesov Anna Kuz Table of contents 1. Executive summary 1 2. Methodology 3 3. Russian pay TV market 2017-2023 5 3.1. Subscriber base, ARPU, revenue 5 3.1.1. Basic pay TV service 5 3.1.2. Additional pay TV services 9 3.1.3. HD and 4К subscriber base 10 3.2. Pay TV market segmentation by technology 14 3.2.1. -

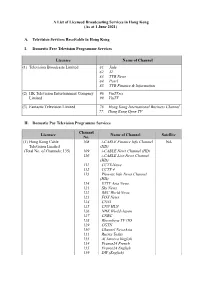

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021)

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021) A. Television Services Receivable in Hong Kong I. Domestic Free Television Programme Services Licensee Name of Channel (1) Television Broadcasts Limited 81. Jade 82. J2 83. TVB News 84. Pearl 85. TVB Finance & Information (2) HK Television Entertainment Company 96. ViuTVsix Limited 99. ViuTV (3) Fantastic Television Limited 76. Hong Kong International Business Channel 77. Hong Kong Open TV II. Domestic Pay Television Programme Services Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. (1) Hong Kong Cable 108 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel NA Television Limited (HD) (Total No. of Channels: 135) 109 i-CABLE News Channel (HD) 110 i-CABLE Live News Channel (HD) 111 CCTV-News 112 CCTV 4 113 Phoenix Info News Channel (HD) 114 ETTV Asia News 121 Sky News 122 BBC World News 123 FOX News 124 CNNI 125 CNN HLN 126 NHK World-Japan 127 CNBC 128 Bloomberg TV HD 129 CGTN 130 Channel NewsAsia 131 Russia Today 133 Al Jazeera English 134 France24 French 135 France24 English 139 DW (English) - 2 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. 140 DW (Deutsch) 151 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel 152 i-CABLE News Channel 153 i-CABLE Live News Channel 154 Phoenix Info News 155 Bloomberg 201 HD CABLE Movies 202 My Cinema Europe HD 204 Star Chinese Movies 205 SCM Legend 214 FOX Movies 215 FOX Family Movies 216 FOX Action Movies 218 HD Cine p. 219 Thrill 251 CABLE Movies 252 My Cinema Europe 253 Cine p. 301 HD Family Entertainment Channel 304 Phoenix Hong Kong 305 Pearl River Channel 311 FOX 312 FOXlife 313 FX 317 Blue Ant Entertainment HD 318 Blue Ant Extreme HD 319 Fashion TV HD 320 tvN HD 322 NHK World Premium 325 Arirang TV 326 ABC Australia 331 ETTV Asia 332 STAR Chinese Channel 333 MTV Asia 334 Dragon TV 335 SZTV 336 Hunan TV International 337 Hubei TV 340 CCTV-11-Opera 341 CCTV-1 371 Family Entertainment Channel 375 Fashion TV 376 Phoenix Chinese Channel 377 tvN 378 Blue Ant Entertainment 502 Asia YOYO TV 510 Dreamworks 511 Cartoon Network - 3 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. -

Optik TV Multicultural Channel Selection Guide Representative’S Name Phone

® Optik TV Multicultural channel selection guide Representative’s name Phone The Essentials and Optik TV Combos Add multicultural channels Build the TV package that’s perfect for you. Whether you want Optik TV Combos a great foundation with the Essentials or the ultimate in-home SOUTH ASIAN CHANNELS ADD THE FOLLOWING CHANNELS TO DESI STARTER PACK FOR $5/MO. EACH. viewing experience with 1 of our 3 combos. DESI STARTER PACK | $15/MO. SELECT OPTIMUM PLATINUM SD ESSENTIALS HD ATN B4U ATN B4U ATN Movies OK Aapka Colors ATN ATN NDTV 24x7 ATN Plus Movies ATN Alpha Music ATN Jaya TV Sony ABP News ATN Aastha ATN MH 1 theme packs theme packs theme packs ETC Punjabi Theme packs 6 of your choice 9 of your choice 11 of your choice Current regular bundled price $35 per month ADD THE FOLLOWING CHANNELS TO DESI STARTER PACK FOR $5/MO. EACH. Note: CRTC guidelines require that certain channels are only available regionally. Current regular SD bundled price $74 $87 $99 HD HD CBN SET Max HD HD HD per month ATN Life OK ATN SAB TV ATN Zoom Big Magic Channel PTC Punjabi Star India Gold Times Now Zee Cinema Zee TV Canada OD ATN Urdu International Punjabi DESI MEGA PACK | $50/MO. HD HD HD HD HD (Not available OD in Kamloops & For full channel offerings, please refer to the Optik TV channel Montreal CBS Seattle Prince George) SD selection guide. HD ATN B4U ATN Movies OK CBN Aapka Colors ATN ATN B4U ATN NDTV 24x7 ATN Plus ATN SAB TV ATN Zoom HD ATN Alpha Movies Music ATN Cricket Plus HD HD ABP News OD ETC Punjabi English & French Seattle Multicultural channels ADD THE FOLLOWING CHANNELS TO DESI MEGA PACK FOR $5/MO. -

Are Science Cities Fostering Firm Innovation?

PRELIMINARY AND INCOMPLETE – DO NOT CITE Are Science Cities Fostering Firm Innovation? Evidence from Russia’s Regions 1 Helena Schweiger Paolo Zacchia European Bank for Reconstruction and University of California – Berkeley Development [email protected] [email protected] February 2015 Abstract: Using a mixture of data from the recent regionally representative Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS) in Russia as well as municipal level data, we find that there are significant differences in innovation activity of firms and cities across the Russian regions. We investigate whether this could be explained by the proximity to science cities – towns with a high concentration of research and development facilities, as well as human capital. They were selected and given this status in a largely random way during Soviet times. We match the science and non-science cities on their historic and geographical characteristics and compare the innovation activity (R&D, product and process innovation) of firms in science cities with the innovation activity of similar-in-the-observables firms in similar, non-science cities. Preliminary evidence suggests that firms located in science cities were more likely to engage in product and process innovation than firms located in similar, non-science cities. The results have important policy implications because many countries in the world, including developing countries, have been introducing science parks or other areas of innovation, viewing them as a type of silver bullet with the capability of dramatically improving a country’s ability to compete in the global economy and help the country to grow. JEL Classification: O33, O38, O14 Keywords: Innovation, Russia, science cities 1 We would like to thank Natalya Volchkova, Sergei Guriev and Maria Gorban for helpful discussions and Irina Capita, Jan Lukšič, Alexander Stepanov and Maria Vasilenko for excellent research assistance.