1 an Annotated Checklist of the Odonata of Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018 Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus) photo by Clifton Avery Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2018 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

© 2016 David Paul Moskowitz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 David Paul Moskowitz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LIFE HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE TIGER SPIKETAIL DRAGONFLY (CORDULEGASTER ERRONEA HAGEN) IN NEW JERSEY By DAVID P. MOSKOWITZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Entomology Written under the direction of Dr. Michael L. May And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION THE LIFE HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE TIGER SPIKETAIL DRAGONFLY (CORDULEGASTER ERRONEA HAGEN) IN NEW JERSEY by DAVID PAUL MOSKOWITZ Dissertation Director: Dr. Michael L. May This dissertation explores the life history and behavior of the Tiger Spiketail dragonfly (Cordulegaster erronea Hagen) and provides recommendations for the conservation of the species. Like most species in the genus Cordulegaster and the family Cordulegastridae, the Tiger Spiketail is geographically restricted, patchily distributed with its range, and a habitat specialist in habitats susceptible to disturbance. Most Cordulegastridae species are also of conservation concern and the Tiger Spiketail is no exception. However, many aspects of the life history of the Tiger Spiketail and many other Cordulegastridae are poorly understood, complicating conservation strategies. In this dissertation, I report the results of my research on the Tiger Spiketail in New Jersey. The research to investigate life history and behavior included: larval and exuvial sampling; radio- telemetry studies; marking-resighting studies; habitat analyses; observations of ovipositing females and patrolling males, and the presentation of models and insects to patrolling males. -

A Checklist of Oklahoma Odonata

Libellula comanche Calvert, 1907 - Comanche Skimmer Useful regional references: Libellula composita (Hagen, 1873) - Bleached Skimmer A Checklist of Libellula croceipennis Selys, 1868 - Neon Skimmer —Dragonflies and damselflies of the West by Dennis Paulson (2009) Libellula cyanea Fabricius, 1775 - Spangled Skimmer and Dragonflies and damselflies of the East by Dennis Paulson (2011) Oklahoma Odonata Libellula flavida Rambur, 1842 - Yellow-sided Skimmer Princeton University Press. Libellula incesta Hagen, 1861 - Slaty Skimmer —Damselflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2011) and (Dragonflies and Damselflies) Libellula luctuosa Burmeister, 1839 - Widow Skimmer Dragonflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2015) University of Texas Press. Libellula nodisticta Hagen, 1861 - Hoary Skimmer Libellula pulchella Drury, 1773 - Twelve-spotted Skimmer —Oklahoma Odonata Project: https://biosurvey.ou.edu/smith/Oklahoma_Odonata.html Libellula saturata Uhler, 1857 - Flame Skimmer Compiled by Brenda D. Smith — Smith BD, Patten MA (2020) Dragonflies at a Biogeographical Libellula semifasciata Burmeister, 1839 - Painted Skimmer Crossroads: The Odonata of Oklahoma and Complexities Beyond its & Michael A. Patten Libellula vibrans Fabricius, 1793 - Great Blue Skimmer Borders. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. Macrodiplax balteata (Hagen, 1861) - Marl Pennant Miathyria marcella (Selys, 1856) - Hyacinth Glider Oklahoma Biological Survey, Micrathyria hagenii Kirby, 1890 - Thornbush Dasher Oklahoma -

Checklist Dragonfly and Damselfly

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com DRAGONFLY AND DAMSELFLY CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 88 species Petaltails ☐ Swift River Crusier ☐ Autumn Meadowhawk ☐ Gray Petaltail (Tachopteryx thoreyi)*∆ (Macromia illinoiensis)*∆ (Sympetrum vicinum)*∆ ☐ Royal River Cruiser ☐ Carolina Saddlebags (Tramea carolina)*∆ Darners (Macromia taeniolata)*∆ ☐ Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata)*∆ ☐ Shadow Darner (Aeshna umbrosa) ☐ Common Green Darner (Anax junius)*∆ Emeralds Broad-winged Damsels ☐ Comet Darner (Anax longipes)*∆ ☐ Common Baskettail (Epitheca cynosura)*∆ ☐ Sparkling Jewelwing ☐ Springtime Darner (Basiaeschna janata)* ☐ Prince Baskettail (Epitheca princeps)*∆ (Calopteryx dimidiata)* ☐ Fawn Darner (Boyeria vinosa) ☐ Selys’ Sundragon (Helocordulia selysii) ☐ Ebony Jewelwing (Calopteryx maculata)*∆ ☐ Swamp Darner (Epiaeschna heros)*∆ ☐ Mocha Emerald (Somatochlora linearis)*∆ ☐ Smoky Rubyspot (Hetaerina titia) ☐ Taper-tailed Darner ☐ Clamp-tipped Emerald Spreadwings (Gomphaeschna antilope)*∆ (Somatochlora tenebrosa)*∆ ☐ Elegant Spreadwing (Lestes inaequalis)* ☐ Cyrano Darner Skimmers ☐ Southern Spreadwing (Lestes australis) (Nasiaeschna pentacantha)*∆ ☐ Four-spotted Pennant ☐ Amber-winged Spreadwing Clubtails (Brachymesia gravida)*∆ (Lestes eurinus)* ☐ Two-striped Forceptail ☐ Calico Pennant (Celithemis elisa)*∆ ☐ Slender Spreadwing (Lestes rectangularis)* (Aphylla williamsoni)*∆ ☐ Halloween Pennant (Celithemis eponina)*∆ ☐ Swamp Spreadwing (Lestes vigilax) ☐ Black-shouldered Spinyleg ☐ -

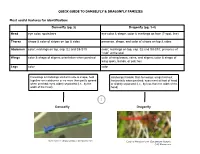

Dragonfly (Pg. 3-4) Head Eye Color

QUICK GUIDE TO DAMSELFLY & DRAGONFLY FAMILIES Most useful features for identification: Damselfly (pg. 2) Dragonfly (pg. 3-4) Head eye color; spots/bars eye color & shape; color & markings on face (T-spot, line) Thorax shape & color of stripes on top & sides presence, shape, and color of stripes on top & sides Abdomen color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10 color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10; presence of “club” at the end Wings color & shape of stigma; orientation when perched color of wing bases, veins, and stigma; color & shape of wing spots, bands, or patches Legs color color Forewings & hindwings similar in size & shape, held Hindwings broader than forewings; wings held out together over abdomen or no more than partly spread horizontally when perched; eyes meet at front of head when perched; eyes widely separated (i.e., by the or slightly separated (i.e., by less than the width of the width of the head) head) 1 Damselfly Dragonfly Vivid Dancer (Argia vivida); CAS Mazzacano Cardinal Meadowhawk (Sympetrum illotum); CAS Mazzacano DAMSELFLIES Wings narrow, stalked at base 2 Wings broad, colored, not stalked at base 3 Wings held askew Wings held together Broad-winged Damselfly when perched when perched (Calopterygidae); streams Spreadwing Pond Damsels (Coenagrionidae); (Lestidae); ponds ponds, streams Dancer (Argia); Wings held above abdomen; vivid colors streams 4 Wings held along Bluet (Enallagma); River Jewelwing (Calopteryx aequabilis); abdomen; mostly blue ponds CAS Mazzacano Dark abdomen with blue Forktail (Ischnura); tip; -

Focusing on the Landscape a Report for Caring for Our Country

Focusing on the Landscape Biodiversity in Australia’s National Reserve System Part A: Fauna A Report for Caring for Our Country Prepared by Industry and Investment, New South Wales Forest Science Centre, Forest & Rangeland Ecosystems. PO Box 100, Beecroft NSW 2119 Australia. 1 Table of Contents Figures.......................................................................................................................................2 Tables........................................................................................................................................2 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................5 Introduction...............................................................................................................................8 Methods.....................................................................................................................................9 Results and Discussion ...........................................................................................................14 References.............................................................................................................................194 Appendix 1 Vertebrate summary .........................................................................................196 Appendix 2 Invertebrate summary.......................................................................................197 Figures Figure 1. Location of protected areas -

Download Download

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 217 (1996) Volume 105 p. 217-223 AN UPDATED CHECKLIST OF INDIANA DRAGONFLIES (ODONATA: ANISOPTERA) James R. Curry Department of Biology Franklin College Franklin, Indiana 46131 ABSTRACT: Published reports of Indiana Odonata appeared more or less regularly from the turn of the century until 1971. Two workers, E.B. Williamson and B.E. Montgomery, were largely responsible for this work, and between them, they reported 100 species of dragonflies (Anisoptera) for Indiana. Williamson published an annotated list of Indiana Odonata in 1917 in which he gave each species a number from 1 to 125. As new species were reported, they were added to the list at the appropriate taxonomic position by adding an a, b, c, and so on to an existing number. Since 1971, no additional published reports have appeared, and changes in classification and nomenclature make an update of the State list of dragonflies necessary. Williamson's numbering system does not fit well with the changes that have occurred, and the author recommends that it be dropped in favor of a more up-to-date listing. Several species reported for the State are no longer recognized, and one species new to Indiana has recently been recorded. Currently, 98 species of dragonflies are recorded for Indiana. KEYWORDS: Anisoptera, Indiana dragonflies, Indiana records, Odonata. INTRODUCTION Systematic surveys of Indiana Odonata, conducted almost annually from the turn of the century by Williamson, Montgomery, and others, ceased in the late 1960s. The surveys were resumed four years ago by the author with the intent to update State records and to develop a field guide to the common species in the State. -

Korean Red List of Threatened Species Korean Red List Second Edition of Threatened Species Second Edition Korean Red List of Threatened Species Second Edition

Korean Red List Government Publications Registration Number : 11-1480592-000718-01 of Threatened Species Korean Red List of Threatened Species Korean Red List Second Edition of Threatened Species Second Edition Korean Red List of Threatened Species Second Edition 2014 NIBR National Institute of Biological Resources Publisher : National Institute of Biological Resources Editor in President : Sang-Bae Kim Edited by : Min-Hwan Suh, Byoung-Yoon Lee, Seung Tae Kim, Chan-Ho Park, Hyun-Kyoung Oh, Hee-Young Kim, Joon-Ho Lee, Sue Yeon Lee Copyright @ National Institute of Biological Resources, 2014. All rights reserved, First published August 2014 Printed by Jisungsa Government Publications Registration Number : 11-1480592-000718-01 ISBN Number : 9788968111037 93400 Korean Red List of Threatened Species Second Edition 2014 Regional Red List Committee in Korea Co-chair of the Committee Dr. Suh, Young Bae, Seoul National University Dr. Kim, Yong Jin, National Institute of Biological Resources Members of the Committee Dr. Bae, Yeon Jae, Korea University Dr. Bang, In-Chul, Soonchunhyang University Dr. Chae, Byung Soo, National Park Research Institute Dr. Cho, Sam-Rae, Kongju National University Dr. Cho, Young Bok, National History Museum of Hannam University Dr. Choi, Kee-Ryong, University of Ulsan Dr. Choi, Kwang Sik, Jeju National University Dr. Choi, Sei-Woong, Mokpo National University Dr. Choi, Young Gun, Yeongwol Cave Eco-Museum Ms. Chung, Sun Hwa, Ministry of Environment Dr. Hahn, Sang-Hun, National Institute of Biological Resourses Dr. Han, Ho-Yeon, Yonsei University Dr. Kim, Hyung Seop, Gangneung-Wonju National University Dr. Kim, Jong-Bum, Korea-PacificAmphibians-Reptiles Institute Dr. Kim, Seung-Tae, Seoul National University Dr. -

Macromia Weerakooni Sp. Nov. (Odonata: Anisoptera: Macromiidae)

International Journal of Odonatology, 24.2021, 169–177 Amila Prasanna Sumanapala* Macromia weerakooni sp. nov. (Odonata: Anisoptera: Macromiidae), a new dragonfly species from Sri Lanka https://doi.org/10.23797/2159-6719_24_13 Received: 22 November 2020 – Accepted: 8 February 2021 – Published: 09 August 2021 Abstract: The genus Macromia is represented in Sri Lanka by two endemic species. In this paper a third presumed endemic species is described based on a single male specimen collected at Kirikitta, Weliweri- ya, Western Province in the low country wet zone of the country. Macromia weerakooni sp. nov. differs from its congeners in Sri Lanka by having turquoise blue eyes, an entirely black labrum, a short yellow ante-humeral stripe, an interrupted yellow stripe on the anterior margin of metepisternum and differences in the secondary genitalia and anal appendages. As this is the only record of the species knowledge of its natural history and distribution is limited. This discovery highlights the need for further systematic sur- veys of Odonata in Sri Lanka using sampling methods suitable for the detection of elusive species. http://zoobank.org/References/8CCEACBE-04C3-4D2E-A69C-C034EFA6E152 Keywords: new species; endemic; South Asia Introduction The genus Macromia Rambur, 1842 is mainly a tropical genus distributed in Australasia, Europe and the Americas and comprises 81 species (Paulson and Schorr, 2020). In South Asia it is represented by 17 species (Kalkman et al., 2020). Out of the 14 species known from India, nine are known from the Western Ghats range (Subramanian et al., 2018), to which the Sri Lankan biodiversity has close affinities with. -

Species Listing PROPOSAL Form: Listing Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Species in Massachusetts

Appendix A Page 1 Species Listing PROPOSAL Form: Listing Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Species in Massachusetts Scientific name: _Gomphus vastus______________ Current Listed Status (if any): _Special Concern___ Common name: _Cobra Clubtail________________ Proposed Action: Add the species, with the status of: ________ Change the scientific name to: _________ X Remove the species Change the common name to: _________ Change the species’ status to: ________ (Please justify proposed name change.) Proponent’s Name and Address: Peter Hazelton Aquatic Ecologist Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581 Phone Number: 508-389-6389 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 508-389-7890 Association, Institution or Business represented by proponent: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Proponent’s Signature: Date Submitted: 2/26/2018 Please submit to: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581 Justification Justify the proposed change in legal status of the species by addressing each of the criteria below, as listed in the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MGL c. 131A) and its implementing regulations (321 CMR 10.00), and provide literature citations or other documentation wherever possible. Expand onto additional pages as needed but make sure you address all of the questions below. The burden of proof is on the proponent for a listing, delisting, or status change. (1) Taxonomic status. Is the species a valid taxonomic entity? Please cite scientific literature. Yes, Gomphus vastus, Walsh 1863 (Paulson & Dunkle 2009) or Gomphurus vastus (Needham et al. -

Biogeographic Evaluation of the Dragonflies and Damselflies in The

Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 15 (2017): 8–29 Fontana–BriaISSN: 1698– et0476 al. Biogeographic evaluation of the dragonfies and damselfies in the Eastern Iberian Peninsula L. Fontana–Bria, E. Frago, E. Prieto–Lillo & J. Selfa Fontana–Bria, L., Frago, E., Prieto–Lillo, E. & Selfa, J., 2017. Biogeographic evaluation of the dragonfies and damselfies in the Eastern Iberian Peninsula. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 15: 8–29. Abstract Biogeographic evaluation of the dragonfies and damselfies in the Eastern Iberian Peninsu- la.— Insects are one of the most diverse groups of animals in terrestrial ecosystems, and are thus a good model system to study macrogeographic patterns in species’ distributions. Here we perform a biogeographical analysis of the dragonfies and damselfies in the Valencian Country (Eastern Iberian Peninsula). We also compare the species present in this territory with those in the adjacent territories of Catalonia and Aragon, and with those present in the whole Iberian Peninsula. Furthermore, we update the list of species of dragonfies and dam- selfies in the Valencian territory (65 species), and discuss the current status of two of them: Macromia splendens and Lindenia tetraphylla. Our results highlight that the Valencian Country has a higher proportion of Ethiopian elements but a lower proportion of Eurosiberian elements than Catalonia and Aragon. We also emphasize the importance of volunteer work in providing new knowledge on this group of iconic insects, and the relevance of museum collections in preserving them. The role of climate change in the distribution of Odonata is also discussed. Key words: Odonata, Valencian Country, Spain, Iberian Peninsula, Biogeography, Climate change Resumen Evaluación biogeográfca de las libélulas y los caballitos del diablo del este de la península ibérica.— Los insectos son uno de los grupos de animales más diversos de los ecosiste- mas terrestres, por lo que constituyen un buen sistema modelo para estudiar los patrones macrogeográfcos en las distribuciones de especies. -

Macromia Alleghaniensis (Odonata: Macromiidae): New for Michigan, with Clarifications of Northern Records

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 48 Numbers 3/4 -- Fall/Winter 2015 Numbers 3/4 -- Article 12 Fall/Winter 2015 October 2015 Macromia alleghaniensis (Odonata: Macromiidae): New For Michigan, with Clarifications of Northern Records Julie A. Craves University of Michigan, Dearborn, [email protected] Darrin S. O’Brien Prairie Oaks Ecological Station Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Craves, Julie A. and O’Brien, Darrin S. 2015. "Macromia alleghaniensis (Odonata: Macromiidae): New For Michigan, with Clarifications of Northern Records," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 48 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol48/iss3/12 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Craves and O’Brien: Macromia alleghaniensis (Odonata: Macromiidae): New For Michigan, 186 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Vol. 48, Nos. 3 - 4 Macromia alleghaniensis (Odonata: Macromiidae): New For Michigan, with Clarifications of Northern Records Julie A. Craves1,2* and Darrin S. O’Brien2 Abstract An Alleghany River Cruiser, Macromia alleghaniensis Williamson (Odo- nata: Macromiidae), collected in Cass County, Michigan on 18 June 2014, rep- resents the first record of the species for the state, as well as the northernmost unequivocal record in North America. Other records north of 40° latitude are clarified and discussed. ____________________ Macromia Rambur is a genus of medium to large (61–91 mm) dragonflies of 84 species worldwide (Garrison et al.