Northern Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption in Cameroon

Corruption in Cameroon CORRUPTION IN CAMEROON - 1 - Corruption in Cameroon © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Cameronn Tél: 22 21 29 96 / 22 21 52 92 - Fax: 22 21 52 74 E-mail : [email protected] Printed by : SAAGRAPH ISBN 2-911208-20-X - 2 - Corruption in Cameroon CO-ORDINATED BY Pierre TITI NWEL Corruption in Cameroon Study Realised by : GERDDES-Cameroon Published by : FRIEDRICH-EBERT -STIFTUNG Translated from French by : M. Diom Richard Senior Translator - MINDIC June 1999 - 3 - Corruption in Cameroon - 4 - Corruption in Cameroon PREFACE The need to talk about corruption in Cameroon was and remains very crucial. But let it be said that the existence of corruption within a society is not specific to Cameroon alone. In principle, corruption is a scourge which has existed since human beings started organising themselves into communities, indicating that corruption exists in countries in the World over. What generally differs from country to country is its dimensions, its intensity and most important, the way the Government and the Society at large deal with the problem so as to reduce or eliminate it. At the time GERDDES-CAMEROON contacted the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung for a support to carry out a study on corruption at the beginning of 1998, nobody could imagine that some months later, a German-based-Non Governmental Organisation (NGO), Transparency International, would render public a Report on 85 corrupt countries, and Cameroon would top the list, followed by Paraguay and Honduras. - 5 - Corruption in Cameroon Already at that time in Cameroon, there was a general outcry as to the intensity of the manifestation of corruption at virtually all levels of the society. -

Country Review Report of Cameroon

Country Review Report of Cameroon Review by the Republic of Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia of the implementation by Cameroon of articles 15 – 42 of Chapter III. “Criminalization and law enforcement” and articles 44 – 50 of Chapter IV. “International cooperation” of the United Nations Convention against Corruption for the review cycle 2010 - 2015 Page 1 of 142 I. Introduction 1. The Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption was established pursuant to article 63 of the Convention to, inter alia, promote and review the implementation of the Convention. 2. In accordance with article 63, paragraph 7, of the Convention, the Conference established at its third session, held in Doha from 9 to 13 November 2009, the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention. The Mechanism was established also pursuant to article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention, which states that States parties shall carry out their obligations under the Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States. 3. The Review Mechanism is an intergovernmental process whose overall goal is to assist States parties in implementing the Convention. 4. The review process is based on the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism. II. Process 5. The following review of the implementation by Cameroon of the Convention is based on the completed response to the comprehensive self-assessment checklist received from Cameroon, supplementary information provided in accordance with paragraph 27 of the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism and the outcome of the constructive dialogue between the governmental experts from Cameroon, Angola and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, by means of telephone conferences, and e-mail exchanges and involving: Angola Dr. -

Gouvernance Urbaine Et Urbanisation De Garoua Simon Pierre Petnga Nyamen1, Michel Tchotsoua2

Syllabus Review 6 (1), 2015 : 155 - 174 N SYLLABUS REVIEW E S Human & Social Science Series Gouvernance urbaine et urbanisation de Garoua Simon Pierre Petnga Nyamen1, Michel Tchotsoua2 1Doctorant en Géographie, Université de Ngaoundéré, BP : 454, [email protected], 2Professeur titulaire des universités, Université de Ngaoundéré, BP : 454, [email protected] Résumé Du petit village créé vers la fin du XVIIIème siècle à l’actuelle Communauté Urbaine, Garoua a connu plusieurs transformations du fait des acteurs de sa croissance. La forme actuelle de la municipalité est la sixième d’une série commencée en 1951 et s’explique a priori par la volonté de l’État du Cameroun d’impulser une dynamique nouvelle à son processus de décentralisation. Cet article analyse l’urbanisation de Garoua en mettant un accent particulier sur le mode de gestion de la ville. L’approche méthodologique est basée sur les analyses des cartes et images satellites, les observations directes de terrain et le traitement des données collectées par entretiens semi-structurés avec les autorités de Garoua, les représentants des organismes impliqués dans le développement urbain et certains habitants de la ville. Les principaux résultats de cette étude relèvent que, les différentes transformations administratives du territoire ont favorisé la multiplication et la diversification des acteurs impliqués dans la gestion urbaine. Ces acteurs ont, dans la plupart des cas, des objectifs différents ou des compétences qui se chevauchent, ce qui fait qu’il subsiste une confusion dans le rôle de chacun d’entre eux et constitue un obstacle à la réalisation de certains projets de développement dans la ville de Garoua. -

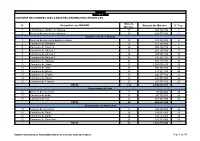

De 40 MINMAP Région Du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES

MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de Garoua 11 847 894 350 3 2 Services déconcentrés régionaux 20 528 977 000 4 Département de la Bénoué 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 283 500 000 6 4 Commune de Barndaké 13 376 238 000 7 5 Commune de Bascheo 16 305 482 770 8 6 Commune de Garoua 1 11 201 187 000 9 7 Commune de Garoua 2 26 498 592 344 10 8 Commune de Garoua 3 22 735 201 727 12 9 Commune de Gashiga 21 353 419 404 14 10 Commune de Lagdo 21 2 026 560 930 16 11 Commune de Pitoa 18 360 777 700 18 12 Commune de Bibémi 18 371 277 700 20 13 Commune de Dembo 11 300 277 700 21 14 Commune de Ngong 12 235 778 000 22 15 Commune de Touroua 15 187 777 700 23 TOTAL 214 6 236 070 975 Département du Faro 16 Services déconcentrés 5 96 500 000 25 17 Commune de Beka 15 230 778 000 25 18 Commune de Poli 22 481 554 000 26 TOTAL 42 808 832 000 Département du Mayo-Louti 19 Services déconcentrés 6 196 000 000 28 20 Commune de Figuil 16 328 512 000 28 21 Commune de Guider 28 534 529 000 30 22 Commune de Mayo Oulo 24 331 278 000 32 TOTAL 74 1 390 319 000 MINMAP / DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 40 MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés Département du Mayo-Rey 23 Services déconcentrés 7 152 900 000 35 24 Commune de Madingring 14 163 778 000 35 24 Commune de Rey Bouba -

Cameroon CAMEROON SUMMARY Cameroon Is a Bicameral Parliamentary Republic with Two Levels of Government, National and Local (Regions and Councils)

COUNTRY PROFILE 2019 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT SYSTEM IN cameroon CAMEROON SUMMARY Cameroon is a bicameral parliamentary republic with two levels of government, national and local (regions and councils). There is constitutional provision for local government, as well as for an intermediary higher territorial tier (regions), although this has yet to be implemented. The main laws governing local government are Law No. 2004/17 on the Orientation of Decentralization, Law No. 2004/18 on Rules Applicable to Councils, and Law No. 2004/19 on Rules Applicable to Regions. The Ministry of Decentralization and Local Government is responsible for government policy on territorial administration and local government. There are 374 local government councils, consisting of 360 municipal councils and 14 city councils. There are also 45 district sub-divisions within the cities. Local councils are empowered to levy taxes and charges including direct council taxes, cattle tax and licences. The most important mechanism for revenue-sharing is the Additional Council Taxes levy on national taxation, of which 70% goes to the councils. All councils have similar responsibilities and powers for service delivery with the exception of the sub-divisional councils, which have a modified set of powers. Council responsibility for service delivery includes utilities, town planning, health, social services and primary education. 1. NATIONAL GOVERNMENT Q Decree 1987/1366: City Council of Douala Cameroon is a unitary republic with a Q Law 2009/019 on the Local Fiscal System 10.1a bicameral parliament. The head of Q Law 2012/001 on the Electoral Code, state is the president, who is directly as amended by Law 2012/017. -

Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 February 2020 Land Use and Land Cover changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon Tchindjang Mesmin; Saha Frédéric, Voundi Eric, Mbevo Fendoung Philippes, Ngo Makak Rose, Issan Ismaël and Tchoumbou Frédéric Sédric * Correspondence: Tchindjang Mesmin, Lecturer, University of Yaoundé 1 and scientific Coordinator of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Saha Frédéric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and project manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Voundi Eric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and technical manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Mbevo Fendoung Philippes PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and internship at University of Liège Belgium; [email protected] Ngo Makak Rose, MSC, GIS and remote sensing specialist at Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring; [email protected] Issan Ismaël, MSC and GIS specialist, [email protected] Tchoumbou Kemeni Frédéric Sédric MSC, database specialist, [email protected] Abstract: Cameroon territory is experiencing significant land use and land cover (LULC) changes since its independence in 1960. But the main relevant impacts are recorded since 1990 due to intensification of agricultural activities and urbanization. LULC effects and dynamics vary from one region to another according to the type of vegetation cover and activities. Using remote sensing, GIS and subsidiary data, this paper attempted to model the land use and land cover (LULC) change in the Centre Region of Cameroon that host Yaoundé metropolis. The rapid expansion of the city of Yaoundé drives to the land conversion with farmland intensification and forest depletion accelerating the rate at which land use and land cover (LULC) transformations take place. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Cameroon: Refugee Sites and Villages for Refugees from the Central African Republic in Nord, Adamaoua and Est Region 01 Jun 2015 REP

Cameroon: Refugee sites and villages for Refugees from the Central African Republic in Nord, Adamaoua and Est region 01 Jun 2015 REP. OF Faro CHAD NORD Mayo-Rey Mbodo Djakon Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier Dompta Goundjel Vina Ndip Beka Yamba Belel Yarmbang ADAMAOUA Borgop Nyambaka Digou Djohong Ouro-Adde Adamou Garga Mbondo Babongo Dakere Djohong Pela Ngam Garga Fada Mbewe Ngaoui Libona Gandinang Mboula Mbarang Gbata Bafouck Alhamdou Meiganga Ngazi Simi Bigoro Meiganga Mikila Mbere Bagodo Goro Meidougou Kombo Djerem Laka Kounde Gadi Lokoti Gbatoua Dir Foulbe Gbatoua Godole Mbale Bindiba Mbonga CENTRAL Dang Patou Garoua-Boulai AFRICAN Yokosire REPUBLIC Gado Mborguene Badzere Nandoungue Betare Mombal Mbam-et-Kim Bouli Oya Ndokayo Sodenou Zembe Ndanga Borongo Gandima UNHCR Sub-Office Garga Sarali UNHCR Field Office Lom-Et-Djerem UNHCR Field Unit Woumbou Ouli Tocktoyo Refugee Camp Refugee Location Returnee Location Guiwa Region Boundary Yangamo Departement boundary Kette Major roads Samba Roma Minor roads CENTRE Bedobo Haute-Sanaga Boulembe Mboumama Moinam Tapare Boubara Gbiti Adinkol Mobe Timangolo Bertoua Bertoua Mandjou Gbakim Bazzama Bombe Belebina Bougogo Sandji 1 Pana Nguindi Kambele Batouri Bakombo Batouri Nyabi Bandongoue Belita II Belimbam Mbile EST Sandji 2 Mboum Kadei Lolo Pana Kenzou Nyong-et-Mfoumou Mbomba Mbombete Ndelele Yola Gari Gombo Haut-Nyong Gribi Boumba-Et-Ngoko Ngari-singo SUD Yokadouma Dja-Et-Lobo Mboy The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 10km Printing date:01 Jun 2015 Sources:UNHCR Author:UNHCR - HQ Geneva Feedback:[email protected] Filename:cmr_refugeesites_caf_A3P. -

ELDRIDGE MOHAMMADOU 15 January 1934–18 February 2004

Africa 74 (4), 2004 OBITUARY ELDRIDGE MOHAMMADOU 15 January 1934–18 February 2004 Eldridge Mohammadou’s body was returned from Nigeria to Cameroon—for a funeral on 29 April 2004 which took place more than two months after his death in Maiduguri. Protective of his privacy to the last, Eldridge had refused medical treatment until he was admit- ted to the university’s teaching hospital. Diagnosed with heart failure, he died only two days later. Friends, family, colleagues and, apparently, even medical staff remained unaware of the severity of his condition to the end. Slipping away undemonstratively in a foreign academy may have been the end he preferred. Despite his many friendships and collegial relations, Eldridge’s reserve makes it impossible to write confidently about the facts of his life, and so this tribute has to be taken only to reflect what one friend was allowed to know about him, and much of that only after his death. Eldridge’s career began in governmental circles, but he went on to make a unique contribution to Cameroonian history both through his own work and by his nurturing others’ projects. According to his curriculum vitae, before he was thirty Eldridge had served as Chief of Cabinet to the Vice-President of the Republic of Cameroon (1962–3), before moving to spend a decade at the Federal Linguistic and Cultural Centre in the Cameroonian capital of Yaounde.´ His next appointment was as Head of the Research Department in the Cultural Division of the Ministry of Education and Culture, during which time his CV also has him studying for a 1973 certificate at the Ecole Pratiques des Hautes Etudes of the Sorbonne in Paris, his only tertiary qualification. -

Republique Du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon

NATIONAL YOUTH POLICY MINJEC CAB 2015 ii H. E. Paul BIYA President of the Republic of Cameroon, Head of State iii iv H.E Philemon YANG, Prime Minister, Head of Government Dr. BIDOUNG MKPATT, Minister of Youth Affairs and Civic Education v vi CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................. IX PREFACE ............................................................................................................................. XII INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1: Geophysical presentation of Cameroon .......................................................................... 3 1.2: Population data and the importance of the youth population in Cameroon ............... 3 1.3: Ethnic groups, Culture and Languages .......................................................................... 4 1.4: Communication and means of communication .............................................................. 4 1.5: Political and Administrative setup .................................................................................. 5 1.6.1 Evolution of the economic situation .................................................................................. 6 1.6.2: The Poverty Situation ....................................................................................................... 7 1.7: International environment .............................................................................................. -

Cameroon Country Study

CAMEROON COUNTRY STUDY Humanitarian Financing Task Team Output IV April 2019 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 1. Key features of the context ............................................................................................... 4 2. HDN policy and operational environment ......................................................................... 6 2.1. Scope of the HDN ....................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Policy, planning and prioritisation environment ....................................................... 8 2.3. Coordination, leadership and division of labour ..................................................... 11 3. Financing across the nexus .............................................................................................. 12 3.1. Wider funding environment .................................................................................... 12 3.2. Funding across the HDN ........................................................................................... 14 3.3. Other considerations in funding across the HDN .................................................... 22 4. Gaps and opportunities ................................................................................................... 23 5. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................... 27 -

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS of CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS OF CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report WRI.ORG Interactive Forest Atlas of Cameroon - Version 3.0 a Design and layout by: Nick Price [email protected] Edited by: Alex Martin TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 4 About This Publication 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms 7 Major Findings 9 What’s New In Atlas Version 3.0? 11 The National Forest Estate in 2011 12 Land Use Allocation Evolution 20 Production Forests 22 Other Production Forests 32 Protected Areas 32 Land Use Allocation versus Land Cover 33 Road Network 35 Land Use Outside of the National Forest Estate 36 Mining Concessions 37 Industrial Agriculture Plantations 41 Perspectives 42 Emerging Themes 44 Appendixes 59 Endnotes 60 References 2 WRI.org F OREWORD The forests of Cameroon are a resource of local, Ten years after WRI, the Ministry of Forestry and regional, and global significance. Their productive Wildlife (MINFOF), and a network of civil society ecosystems provide services and sustenance either organizations began work on the Interactive Forest directly or indirectly to millions of people. Interac- Atlas of Cameroon, there has been measureable tions between these forests and the atmosphere change on the ground. One of the more prominent help stabilize climate patterns both within the developments is that previously inaccessible forest Congo Basin and worldwide. Extraction of both information can now be readily accessed. This has timber and non-timber forest products contributes facilitated greater coordination and accountability significantly to the national and local economy. among forest sector actors. In terms of land use Managed sustainably, Cameroon’s forests consti- allocation, there have been significant increases tute a renewable reservoir of wealth and resilience.