ELDRIDGE MOHAMMADOU 15 January 1934–18 February 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gouvernance Urbaine Et Urbanisation De Garoua Simon Pierre Petnga Nyamen1, Michel Tchotsoua2

Syllabus Review 6 (1), 2015 : 155 - 174 N SYLLABUS REVIEW E S Human & Social Science Series Gouvernance urbaine et urbanisation de Garoua Simon Pierre Petnga Nyamen1, Michel Tchotsoua2 1Doctorant en Géographie, Université de Ngaoundéré, BP : 454, [email protected], 2Professeur titulaire des universités, Université de Ngaoundéré, BP : 454, [email protected] Résumé Du petit village créé vers la fin du XVIIIème siècle à l’actuelle Communauté Urbaine, Garoua a connu plusieurs transformations du fait des acteurs de sa croissance. La forme actuelle de la municipalité est la sixième d’une série commencée en 1951 et s’explique a priori par la volonté de l’État du Cameroun d’impulser une dynamique nouvelle à son processus de décentralisation. Cet article analyse l’urbanisation de Garoua en mettant un accent particulier sur le mode de gestion de la ville. L’approche méthodologique est basée sur les analyses des cartes et images satellites, les observations directes de terrain et le traitement des données collectées par entretiens semi-structurés avec les autorités de Garoua, les représentants des organismes impliqués dans le développement urbain et certains habitants de la ville. Les principaux résultats de cette étude relèvent que, les différentes transformations administratives du territoire ont favorisé la multiplication et la diversification des acteurs impliqués dans la gestion urbaine. Ces acteurs ont, dans la plupart des cas, des objectifs différents ou des compétences qui se chevauchent, ce qui fait qu’il subsiste une confusion dans le rôle de chacun d’entre eux et constitue un obstacle à la réalisation de certains projets de développement dans la ville de Garoua. -

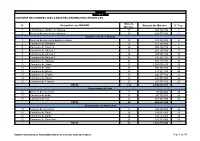

De 40 MINMAP Région Du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES

MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de Garoua 11 847 894 350 3 2 Services déconcentrés régionaux 20 528 977 000 4 Département de la Bénoué 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 283 500 000 6 4 Commune de Barndaké 13 376 238 000 7 5 Commune de Bascheo 16 305 482 770 8 6 Commune de Garoua 1 11 201 187 000 9 7 Commune de Garoua 2 26 498 592 344 10 8 Commune de Garoua 3 22 735 201 727 12 9 Commune de Gashiga 21 353 419 404 14 10 Commune de Lagdo 21 2 026 560 930 16 11 Commune de Pitoa 18 360 777 700 18 12 Commune de Bibémi 18 371 277 700 20 13 Commune de Dembo 11 300 277 700 21 14 Commune de Ngong 12 235 778 000 22 15 Commune de Touroua 15 187 777 700 23 TOTAL 214 6 236 070 975 Département du Faro 16 Services déconcentrés 5 96 500 000 25 17 Commune de Beka 15 230 778 000 25 18 Commune de Poli 22 481 554 000 26 TOTAL 42 808 832 000 Département du Mayo-Louti 19 Services déconcentrés 6 196 000 000 28 20 Commune de Figuil 16 328 512 000 28 21 Commune de Guider 28 534 529 000 30 22 Commune de Mayo Oulo 24 331 278 000 32 TOTAL 74 1 390 319 000 MINMAP / DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 40 MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés Département du Mayo-Rey 23 Services déconcentrés 7 152 900 000 35 24 Commune de Madingring 14 163 778 000 35 24 Commune de Rey Bouba -

Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 February 2020 Land Use and Land Cover changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon Tchindjang Mesmin; Saha Frédéric, Voundi Eric, Mbevo Fendoung Philippes, Ngo Makak Rose, Issan Ismaël and Tchoumbou Frédéric Sédric * Correspondence: Tchindjang Mesmin, Lecturer, University of Yaoundé 1 and scientific Coordinator of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Saha Frédéric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and project manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Voundi Eric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and technical manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Mbevo Fendoung Philippes PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and internship at University of Liège Belgium; [email protected] Ngo Makak Rose, MSC, GIS and remote sensing specialist at Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring; [email protected] Issan Ismaël, MSC and GIS specialist, [email protected] Tchoumbou Kemeni Frédéric Sédric MSC, database specialist, [email protected] Abstract: Cameroon territory is experiencing significant land use and land cover (LULC) changes since its independence in 1960. But the main relevant impacts are recorded since 1990 due to intensification of agricultural activities and urbanization. LULC effects and dynamics vary from one region to another according to the type of vegetation cover and activities. Using remote sensing, GIS and subsidiary data, this paper attempted to model the land use and land cover (LULC) change in the Centre Region of Cameroon that host Yaoundé metropolis. The rapid expansion of the city of Yaoundé drives to the land conversion with farmland intensification and forest depletion accelerating the rate at which land use and land cover (LULC) transformations take place. -

Cameroon: Refugee Sites and Villages for Refugees from the Central African Republic in Nord, Adamaoua and Est Region 01 Jun 2015 REP

Cameroon: Refugee sites and villages for Refugees from the Central African Republic in Nord, Adamaoua and Est region 01 Jun 2015 REP. OF Faro CHAD NORD Mayo-Rey Mbodo Djakon Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier Dompta Goundjel Vina Ndip Beka Yamba Belel Yarmbang ADAMAOUA Borgop Nyambaka Digou Djohong Ouro-Adde Adamou Garga Mbondo Babongo Dakere Djohong Pela Ngam Garga Fada Mbewe Ngaoui Libona Gandinang Mboula Mbarang Gbata Bafouck Alhamdou Meiganga Ngazi Simi Bigoro Meiganga Mikila Mbere Bagodo Goro Meidougou Kombo Djerem Laka Kounde Gadi Lokoti Gbatoua Dir Foulbe Gbatoua Godole Mbale Bindiba Mbonga CENTRAL Dang Patou Garoua-Boulai AFRICAN Yokosire REPUBLIC Gado Mborguene Badzere Nandoungue Betare Mombal Mbam-et-Kim Bouli Oya Ndokayo Sodenou Zembe Ndanga Borongo Gandima UNHCR Sub-Office Garga Sarali UNHCR Field Office Lom-Et-Djerem UNHCR Field Unit Woumbou Ouli Tocktoyo Refugee Camp Refugee Location Returnee Location Guiwa Region Boundary Yangamo Departement boundary Kette Major roads Samba Roma Minor roads CENTRE Bedobo Haute-Sanaga Boulembe Mboumama Moinam Tapare Boubara Gbiti Adinkol Mobe Timangolo Bertoua Bertoua Mandjou Gbakim Bazzama Bombe Belebina Bougogo Sandji 1 Pana Nguindi Kambele Batouri Bakombo Batouri Nyabi Bandongoue Belita II Belimbam Mbile EST Sandji 2 Mboum Kadei Lolo Pana Kenzou Nyong-et-Mfoumou Mbomba Mbombete Ndelele Yola Gari Gombo Haut-Nyong Gribi Boumba-Et-Ngoko Ngari-singo SUD Yokadouma Dja-Et-Lobo Mboy The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 10km Printing date:01 Jun 2015 Sources:UNHCR Author:UNHCR - HQ Geneva Feedback:[email protected] Filename:cmr_refugeesites_caf_A3P. -

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS of CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report

INTERACTIVE FOREST ATLAS OF CAMEROON Version 3.0 | Overview Report WRI.ORG Interactive Forest Atlas of Cameroon - Version 3.0 a Design and layout by: Nick Price [email protected] Edited by: Alex Martin TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 4 About This Publication 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms 7 Major Findings 9 What’s New In Atlas Version 3.0? 11 The National Forest Estate in 2011 12 Land Use Allocation Evolution 20 Production Forests 22 Other Production Forests 32 Protected Areas 32 Land Use Allocation versus Land Cover 33 Road Network 35 Land Use Outside of the National Forest Estate 36 Mining Concessions 37 Industrial Agriculture Plantations 41 Perspectives 42 Emerging Themes 44 Appendixes 59 Endnotes 60 References 2 WRI.org F OREWORD The forests of Cameroon are a resource of local, Ten years after WRI, the Ministry of Forestry and regional, and global significance. Their productive Wildlife (MINFOF), and a network of civil society ecosystems provide services and sustenance either organizations began work on the Interactive Forest directly or indirectly to millions of people. Interac- Atlas of Cameroon, there has been measureable tions between these forests and the atmosphere change on the ground. One of the more prominent help stabilize climate patterns both within the developments is that previously inaccessible forest Congo Basin and worldwide. Extraction of both information can now be readily accessed. This has timber and non-timber forest products contributes facilitated greater coordination and accountability significantly to the national and local economy. among forest sector actors. In terms of land use Managed sustainably, Cameroon’s forests consti- allocation, there have been significant increases tute a renewable reservoir of wealth and resilience. -

Inspection of Embassy Yaoundé, Cameroon

SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED United States Department of State and the Broadcasting Board of Governors Office of Inspector General Office of Inspections Inspection of Embassy Yaoundé, Cameroon General Report Number ISP-I-11-45A, June 2011 Important Notice This report is intended solely for the official use of the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors, or any agency or organization receiving a copy directly from the Office of Inspector General. No secondary distribution may be made, in whole or in part, outside the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors, by them or by other agencies of organizations, without prior authorization by the Inspector General. Public availability of the document will be determined by the Inspector General under the U.S. Code, 5 U.S.C. 552.Improper disclosure of this report may result in criminal, civil, or administrative penalties. Office of Inspector of Inspector Office SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED PURPOSE, SCOPE, AND METHODOLOGY OF THE INSPECTION This inspection was conducted in accordance with the Quality Standards for Inspections, as issued by the President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency, and the Inspector’s Handbook, as issued by the Office of Inspector General for the U.S. Department of State (Department) and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). PURPOSE AND SCOPE The Office of Inspections provides the Secretary of State, the Chairman of the BBG, and Congress with systematic and independent evaluations of the operations of the Department and the BBG. Inspections cover three broad areas, consistent with Section 209 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980: • Policy Implementation: whether policy goals and objectives are being effectively achieved; whether U.S. -

2.3 Cameroon Road Network

2.3 Cameroon Road Network Overview Road Security Axle Load Limits Bridges Road Class and Surface Conditions Distance Matrix Transport corridors CAR Chad Road from Douala to Ngaoundéré Road from Ngaoundéré to Kousseri Road from Ngaoundéré to Touboro Overview According to official statistics, there are about 50,000 km of roads in Cameroon, of which 5,000 km are paved. The road network, both paved and unpaved, is poorly maintained. Road Distance (km) Paved 5,133 Cameroon Road Network Unpaved 12,799 Tracks 59,657 Total 77,589 Classification Administering Agency Network Length National Roads Road Fund Cameroon 7041 km Provincial Roads Road Fund Cameroon 5616 km Departmental Roads Road Fund Cameroon 8075 km Rural Roads (classified) Road Fund Cameroon 12843 km Page 1 Rural Roads (non-classified) Road Fund Cameroon 16100 km The country’s road density is estimated at 7 km for each 1,000 km2. During the wet season, only paved roads remain passable. Traffic on unpaved roads may be restricted by rain barriers. Trucks can therefore be stopped for many hours. On many bridges the traffic of trucks is not allowed. Trucks must use deviations through rivers, but during the rainy season when the waters are high, passing through rivers bank may be impossible. The Road Fund of Cameroon was created in 1996 in order to implement the government policy on the road sector. Government efforts to improve the state /condition of Cameroonian roads are focused on a network of 27,000 km and the process is being undertaken. At N’Gaoundere, on the N1 to Garoua, the tarring process is ongoing. -

Décret N° 2007/117 Du 24 Avril 2007 Portant Création Des Communes Le

Décret N° 2007/117 du 24 avril 2007 Portant création des communes Le président de la République décrète: Art 1er : Sont créées, à compter de la date de signature du présent décret, les communes ci-après désignées: PROVINCE DE L'ADAMAOUA Département de la Vina Commune de Nganha Chef-lieu: Nganha Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Nganha. Commune de Ngaoundéré 1er Chef-lieu: Mbideng Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré 1er. Commune de Ngaoundéré Ile Chef-lieu: Mabanga Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré Ile. Commune de Ngaoundéré Ille Chef-lieu: Dang Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Ngaoundéré Ille Commune de Nyambaka Chef-lieu: Nyambaka Le ressort territorial de ladite commune, couvre l'arrondissement de Nyambaka Commune de Martap Chef-lieu: Martap Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Martap. PROVINCE DU CENTRE Département du Mbam et Inoubou Commune de Bafia Chef-lieu : Bafia Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Bafia. Commune de Kiiki Chef-lieu: Kiiki Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Kiiki Commune de Kon-Yambetta Chef-lieu: Kom- Yambetta Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de KomYambetta Département du Mfoundi Commune d'arrondissement de Yaoundé VII Chef-lieu : Nkolbisson Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Nkolbisson. La composition de la Communauté Urbaine de Yaoundé et le ressort territorial de la commune d'arrondissement de Yaoundé Ile sont modifiés en conséquence 1 PROVINCE DE L'EST Département du Lom et Djerem Commune de Bertoua 1 er Chef-lieu : Nkolbikon Le ressort territorial de ladite commune couvre l'arrondissement de Bertoua 1er. -

The International Tropical Timber Organization

INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER ORGANIZATION ITTO PRE-PROECT PROPOSAL INTITULÉ: SUPPORT TO THE CREATION OF GREEN BELTS AROUND THE WAZA, BENOUÉ, FARO AND BOUBA NDJIDDA NATIONAL PARKS SERIAL NUMBER PPD 178/14 Rev.2 (F) COMMITTEE REFORESTATION AND FOREST MANAGEMENT SUBMITTED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF CAMEROON ORIGINAL LANGUAGE FRENCH SUMMARY The plant formations of the Waza, Faro, Benue and Bouba Ndjidda National Parks are subject to multiple threats that jeopardize their existence. These threats stem from the way subsistence needs of local communities are addressed including their needs for fuel wood and wood material for rural infrastructure and fences, and this situation is maintained through a lack of local initiatives to rehabilitate the degrading plant cover. National Parks are the least degraded areas in the different regions. To reduce the rate of degradation of the plant cover and improve the supply of fuel wood and construction wood in the areas surrounding these parks, it is appropriate to launch a project to establish green belts around these national parks. However, the lack of information required for setting up such project calls for the prior formulation of a pre- project whose implementation will consist in the conduct of baseline studies and the formulation of a full project proposal. EXECUTING AGENCY DIRECTORATE OF WILDLIFE AND CONSERVATION AREAS (DFAP) /MINFOF COLLABORATING AGENCY --- DURATION 6 MONTHS APPROXIMATE STARTING DATE TO BE DECIDED BUDGET AND FUNDING Source Contribution Local currency SOURCES : in US$ equivalent ITTO $ 86,240 Govn’t of Cameroon $ 13,650 TOTAL $ 99,890 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................................. 1 PART 1. PRE-PROJECT CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................... -

Floods and Cholera Epidemic

EPoA Operations Update Cameroon: Floods and Cholera Epidemic DREF Operation no. MDRCM020 GLIDE n° EP-2014-000121-CMR Operations update n° 1 Period covered by this update: 8 September to 5 November, 2014 Operation start date:8 September, 2014 Timeframe: 5 months (End date: 5 February 2015) Operation budget:CHF 308,136 (Initial allocation:CHF 179,304;additional allocation:CHF 128,832) N° of people being assisted: 52,380 (initial number targeted to be assisted was 26,380) Host National Society presence: 25,000 volunteers, more than 50 staff, 58 departmental branches and 250 local branches. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: IFRC Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry of Public Health, Local Administration Authorities Summary: This operations update extends the operation timeframe by an additional 2 months with an additional budget allocation of CHF 128,832 to; Reinforce public outreach / awareness-raising activities in the six localities, which were included in the EPoA (Bibemi, Figuil, Guider, Mayo-Oulo, Pitoa, and Touboro), in an effort to improve the populations’ sanitation and hygiene practices and thus combat the cholera epidemic in 12 districts (six additional districts) of the North Region of Cameroon Extend these activities into the six localities where new cases have been reported (Garoua I, Garoua II, Gashiga, Golombé, Rey Bouba and Tcholiré). The DREF budget revision will cover the training (on Epidemic Control for Volunteers (ECV) manual); and deployment of an Cameroon RC volunteers offloading NFIs in Bibemi. Photo: IFRC additional 50 volunteers and five supervisors (additional 10 volunteers and one supervisor per locality) in five existing localities (Figuil, Guider, Mayo-Oulo, Pitoa, and Touboro); as well as an additional 130 volunteers and 13 supervisors in the six localities where new cases have been reported (Garoua I, Garoua II, Gashiga, Golombe, Rey Bouba and Tcholiré. -

Metwo Silly and Stand

FACTS & FIGURES st st From January 1 to December 31 , 2016 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organization present in Yaounde since 1992, in Maroua since 2013, in Bertoua since 2014 and, in Kousseri since 2015. In accordance with its mandate, the ICRC works to assist victims of armed conflicts and other situations of violence and to promote international humanitarian law. HUMANITARIAN SITUATION: Clashes and violence, according to figures published by ECHO, have led to an estimated 2.9 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in the northern and eastern regions of Cameroon. An estimated 200,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) have been identified in the Adamawa, East, North and Far North regions. These populations who have fled their villages because of violence have mostly found refuge in communities already in a precarious situation. This situation is adversely affecting the limited resources and livelihoods of the host communities. Access to food, drinking water and health care remains extremely difficult. In the four places of detention it regularly visits, the ICRC: HIGHLIGHTS: • built a drinking water supply system in Bertoua, and • 171,957 people received food aid rehabilitated the system in Maroua, while others are being • detainees received basic foodstuff 7,750 rehabilitated in Garoua and Kousseri • water points and boreholes were rehabilitated 67 19 • ensured during 45 days the supply of drinking water at the in the Far North region Maroua Central Prison, following the seasonal and untimely • 61,000 people benefited from improved access to cuts in electricity in the city. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights February 2018 • As of 28 February 2018, less than $100,000 has been received, leaving a 1,810,000 children in need of humanitarian assistance funding gap of $23.3 million – a serious impact on the capacity to 3,260,000 respond to humanitarian needs, particularly with a new crisis emerging people in need in the Anglophone regions (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) • A high-level mission comprised of the Humanitarian Coordinator and the representatives of UNICEF and UNHCR took place in Bamenda and Displacement Mamfe in the North West and South West regions. The mission 241,000 confirmed the growing concerns over the security situation and the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) plight of people affected by this crisis. 69,700 • Since November 2017, over 12,000 people have reportedly returned to Returnees Amchide and Limani, the villages that suffered the brutal attacks by (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) the armed groups affiliated with Boko Haram. Priority needs identified 85,800 by an exploratory mission are health, education and food. Nigerian Refugees in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, Feb 2018) 232,400 UNICEF’s Response with Partners CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and North regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, Feb 2018) Sector UNICEF Sector Total UNICEF Total UNICEF Appeal 2018 Target Results* Target Results* US$ 25.4 million WASH : People provided with 528,000 6,354 75,000 6,354