Holme, Ringer & Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Museum Annex the MUSEUM of KYOTO

The Museum Annex THE MUSEUM OF KYOTO Collaboration between museums, schools, and communities The Museum of Kyoto collaborates with schools and community bodies to offer programs capitalizing on its ample and diverse resources. By so doing, the museum aims to become a vibrant cultural hub for the local community, capable of cultural promotion, human resource building, and further enrichment of the appeal of the local area. We hope that the annex can be one of the essential resources to fulfill the above aims. Supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan in the fiscal 2017 The Museum of Kyoto Sanjo-Takakura, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto 604-8183 Tel 075-222-0888 Fax 075-222-0889 URL http://www.bunpaku.or.jp Design: KRAFTY DESIGN The past and present of the annex building Former Kyoto Branch of the Bank of Japan The Kyoto Branch of the Bank of Japan was moved to the current museum building when it was built in 1906, and remained one of the major banks in this area until its transfer to another location in 1965. History The Kyoto Branch (Shutchojo) of the Bank of Japan is established on Higashinotoin Street, 1894 April to the north of Oike Street. 1903 September Construction of this building starts. June Construction of this building is completed. 1906 July The Kyoto Branch (Shutchojo) of the Bank of Japan is moved to this building. 1911 June The name of the branch is changed from Kyoto Shutchojo to Kyoto Shiten. 1965 October The Kyoto Branch of the Bank of Japan is moved to Kawaramachi Street, to the south-east of Nijo Street. -

Political and Ritual Usages of Portraits of Japanese

POLITICAL AND RITUAL USAGES OF PORTRAITS OF JAPANESE EMPERORS IN EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by Yuki Morishima B.A., University of Washington, 1996 B.F.A., University of Washington, 1996 M.S., Boston University, 1999 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Yuki Morishima It was defended on November 13, 2013 and approved by Katheryn Linduff, Professor, Art and Architecture Evelyn Rawski, Professor, History Kirk Savage, Professor, Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Karen Gerhart, Professor, Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Yuki Morishima 2013 iii POLITICAL AND RITUAL USAGES OF PORTRAITS OF JAPANESE EMPERORS IN EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES Yuki Morishima, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation examines portraits of Japanese emperors from the pre-modern Edo period (1603-1868) through the modern Meiji period (1868-1912) by questioning how the socio- political context influenced the production of imperial portraits. Prior to Western influence, pre- modern Japanese society viewed imperial portraits as religious objects for private, commemorative use; only imperial family members and close supporters viewed these portraits. The Confucian notion of filial piety and the Buddhist tradition of tsuizen influenced the production of these commemorative or mortuary portraits. By the Meiji period, however, Western portrait practice had affected how Japan perceived its imperial portraiture. Because the Meiji government socially and politically constructed the ideal role of Emperor Meiji and used the portrait as a means of propaganda to elevate the emperor to the status of a divinity, it instituted controlled public viewing of the images of Japanese emperors. -

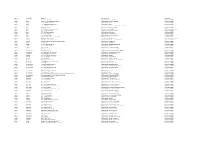

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

Demographic Analysis on the Monorail and Urban Development

S5-5 DEMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS ON THE MONORAIL AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Yuan wen Zhang, Fukuda Hiroatsu, and Yu peng Wang* Faculty of Environmental Engineering, The University of Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu, Japan * Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: Nowadays, typical cities are heavily reliant on automobile cars. which makes the public services inefficient and cities are becoming hollowed out, in this case, cities gradually lose vitality. This study is about the problem which is based on the population alongside the Kitakyushu monorail, people there are looking forward to resolving this issue. In order to learn the situation of the urban development of Kitakyushu alongside the monorail, we conduct a survey in the form of a questionnaire on the population who lived and used the monorail. Keywords: Monorail, Usage Situation, Population, Urban Development 1. BACKGROUND Nowadays, typical cities are heavily reliant on The Kitakyushu monorail is a monorail in Kitakyushu, automobile cars. which makes the public services Fukuoka, Japan, run by the Kitakyushu Urban Monorail Co. inefficient and cities are becoming hollowed out, in this Ltd. (Kitakyushu Kosoku Tetsudo Kabushiki gaisha, case, cities gradually lose vitality. This study is about the literally "Kitakyushu High Speed Railway Co. Ltd."). problem which is based on the population alongside the The Kokura Line (Kokura sen) is currently the only line. Kitakyushu monorail, people there are looking forward to It runs the 8.8 km (5.5 mi) between Kokura station and resolving this issue. In order to learn the situation of the Kikugaoka station in Kokura Minami ward in about 18 urban development of Kitakyushu alongside the minutes. -

Travel Information for ASPEN2009 (Via Hakata Port (Ferry Terminal)) - This Information Will Be Useful When You Go to Venue for APEN2009 from Hakata Port

Travel Information for ASPEN2009 (via Hakata port (ferry terminal)) - This information will be useful when you go to venue for APEN2009 from Hakata port- “Station Hotel Kokura” which is venue for ASPEN2009 connects with JR Kokura Station. “JR” means Japan Railway. Station Hotel Kokura is about 1 minute walk to JR Kokura Station. Map>> http://www.jrhotelgroup.com/eng/hotel/eng145.htm Venu e Flowchart: From Hakata port (ferry terminal) to Station Hotel Kokura (2a) Japan Railway (JR) Kagoshima Honsen Line (1) (Local:100min, 1250JPY) (Rapid: 70min,1250JPY) (Limited Exp.:45min, 2250JPY) Bus Walk (20min, 220JPY) Station (1min) Kokura Port (Ferry Terminal) Port (Ferry (2b) JR Hakata Station JR Shinkansen Hakata (17min, 3500JPY) Station Hotel Kokura (ASPEN2009) 【 At the Hakata Port (Ferry terminal) arrival 】 [1] From Hakata Port (Ferry Terminal) to JR Kokura Station 1. At first, get on a bus “Nishitetsu Bus” at the “Hakata International Terminal” bus stop to “Hakata Station”. (Bus No. 11 , 19 , 50 or 80) Map around Hakata Port>> http://www.routefukuoka.com/top/map/portmap.html http://www.jrkyushu.co.jp/english/port.html Guide for Hakata Port to JR Hakata Station>> http://www.routefukuoka.com/top/porthakata.html Timetable>>http://jik.nnr.co.jp/cgi-bin/Tschedule/table.exe?pwd=gb/table.pwd&from=722285&to=RA0002&kai=N&yb0=H%20&yb1=D%20&yb2=N Single fare: about 220 Yen // Time: about 20 min. (Bus only) 2. Next, transfer to JR trains at JR Hakata Station. (Refer to following (2a) or (2b)) (2a) By JR train Buy a ticket from “JR Hakata Station” to “JR Kokura Station” at “Train-Ticket Center” of JR Hakata Station. -

Kitakyushu Monorail Success Story

Success Story Automatic Ticketing System Enables Smooth Operation of Kitakyushu Urban Monorail Kitakyushu Urban Monorail Co., Ltd., in Japan, selects a new high-performing Allied Telesis solution. Challenge: improving the customer experience Summary Kitakyushu Urban Monorail connects 13 stations across a distance of 8.8km, from Kokura station to Kikugaoka station in Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka, Japan. It was the first urban monorail in Japan. An average of 31,000 people use the monorail daily, including Kitakyushu Urban Monorail students, office workers, and visitors to the Kokura Racecourse. Co., Ltd. Industry: Transport The company acknowledges its responsibility as an infrastructure provider serving many Location: Kitakyushu City, Japan users, and operates under the motto “Safety, Punctuality, and Comfort”. Kitakyushu Established: 1976 Monorail has a very low occurrence of accidents, as it runs above ground, and has no railway crossings. In fact, the monorail has never had a major accident. It is also very Challenge reliable—it can continue to operate under extreme weather conditions such as severe The urban monorail required a new snow, when other transportation services become paralyzed. network to run their new generation ticketing system, and improve the When the monorail first opened, all of its service equipment, including automatic ticket customer experience. gates, ticket machines, and equipment at ticket counters, was connected via an online network. However, this later developed issues, and data from service equipment was Solution then carried using portable media devices. Later, the company adapted their stations’ Allied Telesis provided a brand new, security monitoring network to transmit data, but this was also problematic. centrally-managed network solution utilizing leading-edge technology. -

Kyushu Plant Access

Kyushu Plant Access 1-3, Shinhama-cho, Kanda-machi, Miyako-gun, Fukuoka 800-0395 Phone 093-435-1111(General AffairsSection) For Kitakyushu Airport Introductory notes N rt t ForFor KitakyushuKitakyushu AirportAirport po or ir rp u A Ai For h y ForFor u Kokura us a Access sh y Poplar ky sw KKokuraokura yu wa ita es route PPoplaroplar ak ss Convenience K pr it re Ex CConvenienceonvenience KitakyushuK xp Airport Store SStoretore EExpressway Plant 245 Kuko IC KKukouko IICC For Iriguchi Power FForor IIriguchiriguchi Kokura plant KKokuraokura Matsuyama MatsuyamaMatsuyama 25 Iriguchi 10 IIriguchiriguchi School For FForor Kokura KKokuraokura Mitsubishi Post office MMitsubishiitsubishi Materials MMaterialsaterials For 200m FForor Kokura Bus stop KKokuraokura 254 Kanda Kitakyusyu Pansy Plaza Airport IC PPansyansy PPlazalaza Kanda Elementary School Kanda Thermal KandaKanda ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool KandaKanda ThermalThermal Power Station PPowerower SStationtation Kanda KandaKanda Station SStationtation Baba Elementary School BabaBaba ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool 39 Kanda Town Hall KKandaanda TTownown HHallall 25 Tomihisa Youth House TTomihisaomihisa YYouthouth HHouseouse Kanda Post Office KKandaanda PPostost OOfficeffice Minamibaru Elementary School MMinamibaruinamibaru EElementarylementary SSchoolchool Shinhama Bashi SShinhamahinhama BBashiashi Seven-Eleven SSeven-Eleveneven-Eleven Kanda KandaKanda Taxi TaxiTaxi Area No. 2 gate AreaArea No.No. 2 gategate Kanda-machi North gate KKanda-machianda-machi NNorthorth ggateate Tomihisa-cho -

Book of Abstracts

Book of Abstracts EASIAM 2011 The 7th East Asia SIAM Conference & RIMS Workshop on Methods in Industrial and Applied Mathematics Waseda University, Kitakyushu Campus, June 27-29, 2011 http://www.oishi.info.waseda.ac.jp/~easiam2011/ The 7th East Asia SIAM Conference & RIMS Workshop on Methods in Industrial and Applied Mathematics EASIAM 2011 Kitakyushu Campus, Waseda University, Japan June 27-29, 2011 Book of Abstracts Organaizer East Asia SIAM Co-Sponsors Research Institute for Science and Engineering, Waseda University Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences (RIMS), Kyoto University Numerical Analysis Group, Department of Computational Science and Engineering, Nagoya University Kitakyushu City West Japan Industry and Trade Convention Association Scientific Committee President Hisashi Okamoto (Kyoto University) Vice-President Ming-Chih Lai (National Chiao Tung University) Secretary Shao Liang Zhang (Nagoya University) Ex-President Dongwoo Sheen (Seoul National University) Member Victor Didenko (Universiti Brunei Darussalam) Zhong-Ci Shi (Chinese Academy of Sciences) Tao Tang (Hong Kong Baptist University) Wai-Ki Ching (University of Hong Kong) L. H. Wiryanto (Bandung Institute of Technology) Hendra Gunawan (Bandung Institute of Technology) Hyung-Chun Lee (Ajou University) Byeong-Chun Shin (Chonnam National University) Xiao-Qing Jin (University of Macau) Haiwei Sun (University of Macau) Mohd Omar (University of Malaya) Abdul Rahni (Universiti Sains Malaysia) Rafael P. Saldana (Ateneo de Manila University) Weizhu Bao (National University of Singapore) Zuowei Shen (National University of Singapore) I-Liang Chern (National Taiwan University) Yongwimon Lenbury (Mahidol Univeristy) Pham Ky Anh (Vietnam National University) Nguyen Van Huu (Hanoi University of Science) 1 Greeting The 7th East Asia SIAM Conference & RIMS Workshop on Methods in Industrial and Applied Mathematics will be held at Kitakyushu Campus, Waseda University, Japan. -

Location Map ○Japan

Location Map ○Japan Fukuoka is roughly Here!! Tokyo 1,000 km from Tokyo. Fukuoka Prefecture Kyushu Island ○Fukuoka Prefecture Kitakyushu City Kokura region Here!! JR Kyushu (local train) Kitakyushu Airport Hakata port international terminal Shinkansen Busan, (High-speed rail way) Korea (Ferry) Kitakyushu city is 70 km from Fukuoka Airport. Kitakyushu city is 25 km from Kitakyushu Airport. Fukuoka Airport ○Kitakyushu City, Kokura region Conference venue: Kitakyushu International Conference Center Shinkansen (High-speed rail way) JR Kokura station Bus Station from/to Airport Kitakyushu International Conference Center is about 500 m from Kokura Station, a 5-minute walk. ○ From JR kokura station to venue Conference venue !! Bus Station from/to Airport Kitakyushu International Conference Center is about 500 m from Kokura Station, a 5-minute walk. ○Bus station (Kokura ekimae bus stop) JR Kokura station ① To Kitakyushu Airport ⑥ From Kitakyushu Airport From Fukuoka Airport To Fukuoka Airport From Fukuoka Airport By Bus: Fukuoka Airport Nishitetsu Limited Express Bus. http://www.fuk-ab.co.jp/english/bus.html 1h 40min (¥1,230) Kokura Bus station (Kokura ekimae bus stop). By Train: Fukuoka Airport Fukuoka city subway. http://www.fuk-ab.co.jp/english/subway.html 6 min (¥260) JR Hakata station JR kagoshima trunk line. 70min by fast train (¥1,290). JR Limited Express line. 40min (¥2,110). Shinkansen. 16min (¥3,400). http://www.hyperdia.com/en/ JR Kokura Station From Hakata port international terminal (Busan, Korea Fukuoka ) By Bus: Hakata port Bus #11 or #19. 20min (¥230) JR Hakata station (Hakata ekimae A bus stop). JR kagoshima trunk line. 70min by fast train (¥1,290). -

A Variety of Lessons, a Variety of Discoveries

Students have a valuable opportunity to experience different cultures through Himeshima The School Excursion Program welcomes you to drop by the ‘School Exchange’ OITA Oita Prefecture. 31 It is a program that aims to give students the ability to have fun whilst learning. 653 544 ACCESS MAP We have everything here to aid students’ learning and development. NAKATSU 654 KIBI 213 23 Kunisaki HIGASINAKATU 213 YANAGIGAURA BUZENNAGASU IAMDU 29 AMATSU BUZENZENKOUJI 23 Bungotak29ada 55 10 44 5 An introduction to the achievements of the School Exchange program 10 31 O TOKY USA 34 To 1.Safety, security and a high standard of hospitality 212 655 Usa IC 651 OSAKA NISIYASHIKI To To NAGOYA 387 10 TATEISHI In 2010, over 2000 participants came to Oita Prefecture in the Educational School Visits program. To South Korea 2 Innai IC Kitsuki 34 (Seoul) With uniquely Japanese sightseeing destinations such as Beppu and Yufuin, and the The school exchange took place in a number of schools throughout the prefecture. Through the NAKAYAMAGA OITA Airport Ajimu IC Oita airport road 500 Usa Usa beppu road presence of the International University for exchange students, there is a sense of 28 Aki IC introductions of their respective traditional cultures, the exchange of differences in lifestyle and 496 Oita agricultural Kitsuki IC cultural park IC KITSUKI Nakatsu 500 Fujiwara JCT a) familiarity in the area. Visitors from overseas will be able to enjoy the Educational School 213 Osak culture, students were able to achieve a valuable understanding of other cultures. Hiji IC a~ Hayami IC suyam OOGA Mat HIJI u~ OOTURU 212 50 Bepp Visit in a secure, hospitable environment. -

Kyushu Railway Company (JR Kyushu) Corporate Planning Headquarters, Management Planning Department

20 Years After JNR Privatization Vol. 2 Kyushu Railway Company (JR Kyushu) Corporate Planning Headquarters, Management Planning Department Introduction The Last 20 Years JR Kyushu celebrated the 20th anniversary of its Operating results establishment on 1 April this year. During this time, the Table 1 shows the operating results for the last 20 years. company has tried to assure the safety of its railway Fiscal 1987—the first business year—saw operating losses operations, improve services, and revitalize the local area. of ¥28.8 billion with a current profit of ¥1.5 billion. In In addition, we have promoted efficiency, positively the subsequent economic boom years until 1992, JR expanded railway-related businesses and tried to Kyushu made continuous efforts to improve and steadily strengthen our management base. Although the worst expand its railway-related businesses. The recession operating loss was ¥1.5 billion in FY1987, operating starting in 1992 saw non-operating profits drop along profits of ¥1.5 billion were achieved in FY2006. The with the first ever drop in year-on-year current profits. In company is targeting profits of ¥10 billion in FY2008 and FY1993, year-on-year transport-related profits dropped is putting business on a sound footing. too due to fiercer competition with other transport modes This article looks at the last 20 years and future business and natural disasters and by the end of FY1994, both developments from both the hardware and ‘software’ operating and non-operating profits had dropped further, aspects, including railway-related businesses expansion, pulling JR Kyushu into the red for the first time. -

Q- Kitakyushu Hospitality Roads

Travel Guide of Scenic Byway Kyushu Q-❹ Kitakyushu Hospitality Roads Kitakyushu City in Fukuoka Pref.-World Industrial Heritage in Meiji, Kokura Castle, and Nagasaki-kaido Road Kitakyushu City in the northeastern part of Kyushu faces the Hibikinada Sea (2) Monument of Kyushu and the Kanmon-kaikyo Straits, and its Survey by Mr. Tadataka Ino. peninsula in the eastern is Moji Ward, which is connected to Shimonoseki City at the southwestern end of Honshu Main Island by three tunnels and one bridge. As a result, the two are no longer one and play an important role in the formation and governance of the country as a whole (see Photo (1) and map). The scenic spot of “Kitakyushu Hospitality Roads” is the orange shaded areas displayed on the map from the Moji Ward to the Koyanose area of Yahata-nishi Ward, and the main route is the historic "Nagasaki Kaido" road. However, in the current road network, Kitakyushu City is developing as an industrial city with many national roads, so it has a complicated route. In other words, in the current road network, the major roads from Kanmon Bridge to the Koyanose district are given Q-❹ Kitakyushu Hospitality Roads by National Roads 2, 3, 200 and 211, and some prefecture roads have been developed to supplement them. In addition, National Road 199 (included Road No. 198) for port logistics are parallel to the National road 3 and can be used for this scenic sightseeing. [Access] The main access points to the scenic region are Kitakyushu Airport and Kokura Station on the Sanyo Shinkansen.