Dynamic Alliance Capability As a Business Innovation Enabler Towards Sustained Economic Development: an Empirical Study of Organizational Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finance Vietnam News

finance & business news 21 June 2021 FINANCE . 2 IPs in Dong Nai take measures to prevent COVID spread Reference exchange rate up strongly at week's beginning 2 from HCM City 35 Bank deposits grow slowly amid low interest rates 2 Contactless delivery in pandemic in HCM City 35 Delicate balance needed to address Vietnam's property Hairdressers, manicurists make house calls to survive Covid 36 risks: HSBC. 2 Coworking space companies respond to Covid with new solutions 37 Credit increases steadily, where has capital flown? 3 HCM City business premises rents continue downward spiral 38 TPBank approved to increase charter capital by VND1 trillion 4 Bac Giang compiles three scenarios for lychee WB warns of shrinking production amid COVID-19 outbreak 5 consumption amid Covid-19 39 Positive factors in place for economic growth in 2021 6 Points of sale in quarantine areas proposed to resume Vietnam's path to prosperity 8 operations soon 40 Will 24 years be enough for Vietnam to become a Free rides to COVID vaccination centres: Gojek's week-long offer 40 developed country with high income? 9 Japfa Vietnam donates $1 million to the COVID-19 vaccine fund 40 Overhaul in motion for ODA utilisation 11 Taiwanese footwear maker suspends 18,000 workers Multitude of options on table for further tax interventions 13 over Covid-19 linkage 41 Squid exports to China continue to surge 15 Many provinces and cities ask for 5G coverage 41 Fertiliser prices continue to increase: MoIT 15 Vietnamese lychees confident of winning over consumer Feed price increase drives -

WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO Contents Chairman’S Note

ISSUE 5 SPIRIT WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO Contents Chairman’s Note 03 Chairman’s Note 44 Fantasy on Ice Vision 2030 promised that sport could be used professional training of coaches and other sport 45 Star Performance as a strategy for nation building. Up until that specialists contributing to athlete development 04 Journeys Through Sport 46 Synchronous Motion point in our history, we were asking “how can in Singapore. 06 Celebrate Living With ActiveHealth 47 Flying on Water we get people to play more sport?” Vision 07 Doing Burpees for Good 48 A Better Pedal 2030 changed that question to “how can sport Another example, is the Singapore Sport 08 Everyone Can Play! 50 Matching Effort with Ability change our aspirations and our strategies to Science Symposium – a new national event 10 October Is Tennis Month 51 Rulers on Court help us live better lives?” to share the best practices on activating 11 Unbeatable Spirit Makes History 52 Victory Through Sudden Death! sport science for better results by Singapore 12 Singapore Football Week Kicks Off! 54 Sailing Towards Gold The how has become increasingly clear Sport Institute and the National Youth Sports 13 Showing Solidarity for Persons with Disabilities through the Vision 2030 recommendations. Institute. As more coaches learn and adopt 56 Bountiful Harvest of 50 14 Knowledge Sharing Strengthens Some 680,000 people took part in our annual the best that science has to offer, we can look Sport Ecosystem 58 Always Looking Ahead celebration of National Day through sport, forward to greater success at the major games 15 Twins Win Bronze at 60 A Regular Straight Arrow GetActive! Singapore. -

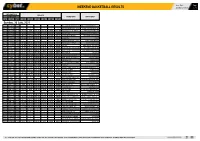

Weekend Basketball Results 26/07/2021 09:04 1 / 4

Issue Date Page WEEKEND BASKETBALL RESULTS 26/07/2021 09:04 1 / 4 INFORMATION RESULTS GAME CODE HOME TEAM AWAY TEAM No CAT TIME 1Q 2Q HT 3Q 4Q FT Sunday, 25 July, 2021 9001 AUBVW 06:00 : : : : : : BULLEEN BOOMERS (W) SOUTHERN PENINSULA .. 9002 AUBVW 06:00 : : : : : : WYNDHAM BASKETBALL.. HAWTHORN MAGIC (W) 9003 AU1WN 06:00 38:17 28:4 66:21 26:20 25:14 117:55 TOWNSVILLE FLAMES (.. CAIRNS DOLPHINS (W) 9004 AU1WN 07:00 24:23 23:17 47:40 8:21 23:28 78:89 SC RIP (W) NORTHSIDE WIZARDS (.. 9005 AU1WE 07:00 24:12 37:19 61:31 17:23 17:18 95:72 MANDURAH MAGIC GOLDFIELDS GIANTS 9006 OGGB 07:40 32:22 14:21 46:43 26:25 10:24 82:92 GERMANY ITALY 9007 AUBV 08:00 : : : : : : WYNDHAM BASKETBALL HAWTHORN MAGIC 9008 AU1N 08:00 21:24 23:16 44:40 14:24 16:26 74:90 TOWNSVILLE HEAT CAIRNS MARLINS 9009 AU1N 09:00 21:24 24:19 45:43 29:14 15:17 89:74 SC RIP NORTHSIDE WIZARDS 9010 PHILC 09:00 21:21 24:31 45:52 18:27 23:9 86:88 NORTHPORT BATANG PI.. BLACKWATER ELITE 9064 PHILC 09:00 21:21 24:31 45:52 18:27 23:9 86:88 NORTHPORT BATANG PI.. SAN MIGUEL BEERMEN 9011 OGGB 11:20 23:23 20:17 43:40 15:12 26:15 84:67 AUSTRALIA NIGERIA 9012 PHILC 11:35 22:22 24:20 46:42 21:14 22:23 89:79 MAGNOLIA HOTSHOTS BARANGAY GINEBRA 9076 VIET 12:00 20:33 20:31 40:64 24:23 32:18 96:105 NHA TRANG DOLPHINS SAIGON HEAT 9013 EC20B 13:00 23:18 22:10 45:28 22:22 23:32 90:82 FRANCE U20 TURKEY U20 9014 PHILC 14:00 23:25 18:19 41:44 32:23 35:27 108:94 NLEX ROAD WARRIORS COLUMBIAN DYIP 9015 OGGA 15:00 15:22 22:23 37:45 25:11 21:20 83:76 FRANCE USA 9052 BR2LB 15:00 18:20 17:11 35:31 14:20 24:26 73:77 MINAS TENIS CLUBE U22 CERRADO BASQUETE U. -

MatthewVanPelt

MatthewVanPelt Mattvp.com | Vpsmglobal.com | [email protected] | References: Available Upon Request | Education BACHELOR’S DEGREE | SPRING ARBOR UNIVERSITY | MAY 2013 · Major: English Writing · Minor: Communications Experience PRESIDENT & FOUNDER | VAN PELT SPORTS MANAGEMENT | 2015- PRESENT - I run a sports management company that helps free agent basketball players and coaches obtain offers from teams overseas. I run exposure camps, do agent-related work, create highlight films for players, train players, and offer resume advice as well as run camps for schools, pro teams, and youth academies in various countries. ASSISTANT BASKETBALL COACH | SAIGON HEAT | 2019 - PRESENT - I serve as the assistant basketball coach for the Saigon Heat in the Asean Basketball League. ASSISTANT BASKETBALL COACH | VIETNAM NATIONAL TEAM | 2019 - PRESENT - I serve as an assistant basketball coach and player development coach for the Vietnam National Team in preparation for the 2019 SEA-Games in Manila, Philippines. LEAD SKILLS COACH & TRAINER | SPORTS SKILLS ACADEMY | 2019 - PRESENT - I coach U11-U17 teams in player development for one of the top basketball academies in Vietnam. ACADEMY COACHING CONSULTANT | VARIOUS VIETNAM BASKETBALL ACADEMIES | 2018 - PRESENT - I am in charge of placing coaches with three different basketball academies (E-Balls, ASA, and SSA) in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. In 2018 (my first year working with these academies), I sent 11 coaches to Vietnam. PROFESSIONAL INTERNATIONAL BASKETBALL PLAYER | 2013 - 2019 - I have experience playing as a professional point guard in Australia, Malaysia, U.S.A., Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, French Polynesia, Canada, Hong Kong, Italy, Ireland, and Switzerland. I have won multiple championships,twoMVP’s,arunner-up MVP, been All-League multiple times, led multiple leagues in assists, and led multiple leagues in scoring, all of which is on my playing resume (this is available upon request). -

Ready for a Changing Journey

04 05 P The road beyond P Motor sport COVID-19: how prepares to fuel travel is adapting up for the future / The pandemic has had / Pursuing sustainability, COVER a huge impact on mobility POWER the pinnacle of motor STORY patterns, but which trends SHIFT sport is researching are here to stay? advanced fuels 04 06 P Racing towards P Jochen Rindt: sustainability Formula 1’s on two wheels lost champion / Formula E driver Lucas / Marking 50 years since ssue ELECTRIC Di Grassi is on a mission TRIUMPH AND the death of grand prix #32 DREAMS to take green motor sport TRAGEDY racing’s only posthumous to the limits – by scooter title-winner Ready for a changing journey FIAAutoMagazine_11_20.indd 1 02.11.20 16:01 AUTO MAGAZINE • 280 x 347 mm PP • Visuel : PILOT SPORT • Remise le 4 novembre • Parution 2020 BoF • BAT MICHELIN PILOT SPORT VICTORIES IN A ROW AT THE HOURS OF LE MANS t-Ferrand. – MFP Michelin, SCA, capital social de 504 000 004 €, 855 200 507 RCS Clermont-Ferrand, place des Carmes-Déchaux, 63000 Clermon Michelin Pilot Sport The winning tire range. Undefeated at The 24 Hours of Le Mans since 1998. MICHELIN Pilot Sport (24 Hours of Le Mans Winner), MICHELIN Pilot Sport Cup 2 Connect, MICHELIN Pilot Sport 4S. MICH_2011010_Pilot_Sport_560x347_Auto_Magazine.indd Toutes les pages 04/11/2020 18:02 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA Dear reader, dear friend, Editorial Board: Jean Todt, Gérard Saillant, THE FIA THE FIA FOUNDATION Freedom of movement is one of the great benets of everyday life that Saul Billingsley, Olivier Fisch Editor-In-Chief: Justin Hynes in the past many of us have too often take for granted. -

Despite Tragic War Events, Vietnam Has for Years Been and Still Is, an Attractive Destination for Backpackers and Tourists

Despite tragic war events, Vietnam has for years been and still is, an attractive destination for backpackers and tourists. Vietnam is intriguing in so many ways, but my top reason is the food and the culture. So, where in earth is Vietnam? Vietnam shares borders with China in the north, Laos and Cambodia to the east. You can easily visit Vietnam from Laos and Cambodia through land crossings (PS: Check Vietnam visa rules). I (the editor) haven't been to Vietnam myself, but my cousin and friends have been there. All tips and advice on Vietnam are theirs! • Did you know that Vietnam is one of the few Communist states in the World, along with Laos, Cuba, China and North Korea? Almost 90 million people live in Vietnam. The capital is Hanoi and the largest city is Ho Chi Minh City (or Saigon). • Did you know that Nguyen is the most common family name in Vietnam? About 40% of the population is named Nguyen, but it feels more like 80%. Almost everybody I met in Vietnam, had Nguyen as their last name. In Norway, every Vietnamese I know has Nguyen as their last name. I bet you know someone too. • Did you know that Vietnam is the world's top exporter of rice (as of September 2012) with 4,6 million tones shipped overseas? India ranks as second best and Thailand as third. • Did you know that Halong Bay in north Vietnam comprises of nearly 2000 limestone islands? • Did you know that Vietnamese people eat more dried noodles than any other country in Asia, even Japan? • Did you know that Vietnamese New Year is called Tet? It's the most important festival in Vietnam. -

Armchair Travel Destination - Vietnam

Armchair Travel _ Destination - Vietnam _ Interesting Facts Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula. It has an area of 331,210 square km. Hanoi is the country’s capital and Ho Chi Minh City is its largest city. Vietnamese is the official language of Vietnam. Its official currency is Dong (VND). It is bordered by three countries – China, Laos, and Cambodia. These interesting facts about Vietnam, explore how fascinating the country has become over the years; with beautiful scenery, amazing cuisine, and an awesome kaleidoscope of cultures. Vietnam’s history and culture Legend has it that the peoples of this land originated from a union between an immortal Chinese princess and “The Dragon Lord of the Seas.” The country’s name was originally spelled as two words, Viet Nam. Their culture is a complex adaptation of Chinese, Japanese, French and American colonial influences. In 938 AD, the Vietnamese developed a trade system to exchange animal skins, ivory and tropical goods for Chinese scrolls on administration, philosophy and literature. The body of their first president Ho Chi Minh (Uncle Ho) was embalmed, and is on display in a mausoleum. Their flag consists of a golden star with five points to represent farmers, workers, intellectuals, youth, and soldiers. The red background pays tribute to the bloodshed during the wars. © Copyright [email protected] 2019. All Rights Reserved 1 Armchair Travel _ Destination - Vietnam _ The national flag of Vietnam. Traditional Vietnamese culture revolves around the core values of humanity, community, harmony, and family. -

Download Journal

Publisher: International Journal of Health, Physical Indian Federation of Computer Science in Education and Computer Science in sports sports ISSN 2231-3265 (On-line and Print) Journal www.ijhpecss.org and www.ifcss.in Impact factor is 5.115.Journal published under the auspices of Quarterly for the months of March, June, International Association of Computer Science September and December. IJHPECSS is in sports refereed Journal.Index Journal of Directory of Email:[email protected] Research Journal Indexing, J-Gate, 120R etc International Journal of Health, Physical Editorial Board Education and Computer Science in Sports is Chief Editor: multidisciplinary peer reviewed journal, mainly Prof. Rajesh Kumar, India publishes original research articles on Health, Editors: Physical Education and Computer Science in Sports, including applied papers on sports Prof.Syed Ibrahim, Saudi Arabia sciences and sports engineering, computer and Prof.L.B.Laxmikanth Rathod, India information, health managements, sports medicine etc. The International Journal of Associate Editors: Health, Physical Education and Computer Prof. P.Venkat Reddy, India Science in sports is an open access and print Prof. J.Prabhakar Rao, India International journal devoted to the promotion Dr.Quadri Syed Javeed, India of health, fitness, physical Education and Dr.Kaukab Azeem, India computer sciences involved in sports. It also provides an International forum for the Members: communication and evaluation of data, Prof.Lee Jong Young, Korea methods and findings in Health, Physical Prof.Henry C.Daut, Philippines education and Computer science in sports. The Prof.Ma. Rosita Ampoyas-Hernani, Philippines Journal publishes original research papers and Dr. Vangie Boto-Montillano, Philippines all manuscripts are peer review. -

World Television

WORLD TELEVISION Heineken 2016 Financial Markets Conference Laurent Theodore and Nguyen Phung Hoang Heineken - 2016 Financial Markets Conference Laurent Theodore and Nguyen Phung Hoang Heineken Laurent Theodore, Commercial Director, Vietnam Brewery Ltd Nguyen Phung Hoang, Marketing Manager Tiger, Vietnam Brewery Ltd QUESTIONS FROM Unidentified Analysts Page 2 Heineken - 2016 Financial Markets Conference Laurent Theodore and Nguyen Phung Hoang Passion for Commercial Excellence Laurent Theodore, Commercial Director, Vietnam Brewery Ltd Welcome back after lunch. My name is Laurent Theodore. It is 17 years that I work for Heineken, started in Heineken France some time ago, and I had different postings in mature and emerging markets, Russia, the US, Congo - Congo Brazzaville, and now Vietnam for the last nearly two years. So it's my pleasure to take you through the commercial agenda of VBL in Vietnam. So the presentation will cover the consumers - some evolutions in the Vietnamese market landscape, and obviously the commercial strategy that we deploy within VBL. The Vietnamese markets, as you can see on this picture - it's very clear - the Vietnamese market is not one single consumer market; you have really different types of consumers. On the left side, you have traditional Vietnam in Mekong Delta, 50km south of Ho Chi Minh City. But also what you have on the right side, you have a picture from Ho Chi Minh City - vibrant, sophisticated consumers - modern. And this picture could have been taken indeed in any parts of big urban centres in the world. So this is Vietnam, a country of polarising and interesting consumer trends happening in this market. -

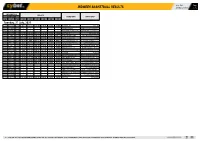

Midweek Basketball Results 28/07/2021 09:10 1 / 6

Issue Date Page MIDWEEK BASKETBALL RESULTS 28/07/2021 09:10 1 / 6 INFORMATION RESULTS GAME CODE HOME TEAM AWAY TEAM No CAT TIME 1Q 2Q HT 3Q 4Q FT Tuesday, 27 July, 2021 2474 OLWGB 07:40 20:17 12:27 32:44 18:26 22:11 72:81 NIGERIA (W) USA (W) 2591 CHGDC 08:30 : : : : : : BEIJING EAGLE UNDEFEATED KING KON.. 2592 CHGDC 10:00 : : : : : : WENZHOU FLYING EAG.. DISDAIN THE GOLDEN LI.. 2475 OLWGC 11:20 17:21 24:16 41:37 16:19 13:29 70:85 AUSTRALIA BELGIUM (W) 2815 VIET 12:00 31:22 27:14 58:36 29:18 23:17 110:71 HANOI BUFFALOES NHA TRANG DOLPHINS 2476 OLWGC 15:00 17:32 9:21 26:53 13:18 16:26 55:97 PUERTO RICO (W) CHINA 2477 BR2LB 15:00 22:16 19:6 41:22 24:17 29:18 94:57 CR FLAMENGO RJ U22 CERRADO BASQUETE U.. 2478 BR2LB 15:00 9:22 10:17 19:39 20:31 8:21 47:91 PATO BASQUETE U22 ADRM MARINGA U22 2816 VIET 16:00 23:21 22:13 45:34 15:16 21:16 81:66 SAIGON HEAT VIETNAM NATIONAL BA.. 2479 BR2LB 17:15 22:28 18:18 40:46 14:20 9:19 63:85 BRB/BRASILIA U22 BAURU BASKET SP U22 2480 BR2LB 17:15 20:8 15:18 35:26 21:16 17:17 73:59 SC CORINTHIANS PAULI.. CORITIBA MONSTERS U.. 2897 INF 19:00 23:22 21:18 44:40 24:23 22:14 90:77 JORDAN TUNISIA 2481 BR2LB 19:30 4:22 8:27 12:49 8:31 25:25 45:105 BASKET CEARENSE U22 RIO CLARO BASQUETE . -

Bangkok Storm V2.Indd

COMMERCIAL SPONSORSHIP & PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES THE STORM IS COMING BANGKOK STORM Bangkok Storm Basketball Club is a newly established professional basketball QUICK FACTS team based in Bangkok, Thailand with plans to compete regionally in the ASEAN Basketball League 2019-2020 (ABL) as well as in other international competitions FULL NAME Bangkok Storm throughout the world. FOUNDED 2019 STADIUM Nimibutr Stadium Bangkok Storm’s ambition is to be one of the leading professional sports CAPACITY 5,600 Spectators organisations in South East Asia playing at the highest levels regionally and COLOURS Black & Gold internationally and providing businesses with an opportunity to link in with LEAGUE ASEAN Basketball League one of the world’s most popular sports. PRESIDENT Kevin Yurkus FOUNDER Martyn Ford Bangkok Storm has no immediate plans to play in the Thai leagues, focusing on preparing for the ABL. Played in 213 countries, with more than 450 million registered players worldwide, basketball is the second In 2018-2019 the ABL consists of: largest sport in the world. With an audience of 1 billion • 10 Teams from 10 countries throughout 150+ countries, basketball is hot on the • 2.2+ Billion Fanbase heels of football in terms of global sports dominance. • TV Audience 600+ million Bangkok Storm is offering a world-class basketball product backed by for- Be Part Of Bangkok Storm Experience - ward-thinking vision, industry-leading customer service and cutting-edge Become A Commercial Partner community outreach and promotion. We have a number of commercial Sponsorship and partnership opportunities for businesses to get involved with Bangkok Storm including: Club Title Sponsor; Club Partners; Official Supplier Partners & Official Media Partners; Game Night and Special Event Partners. -

March 2019 the Sporting Life

O I VIET NA M VIETNAM 03-2019 THE SPORTING LIFE Forgotten Voices A Revival of Saigon’s Golden Age of Music PAGE 20 Got the Thirst? Free Water Top Up at refill Stations Across Southeast Asia PAGE 24 Echoes of Asia in L.A. For Hollywood magic and Asian diversity, visit the City of Angels PAGE 64 03 - 2 01 9 NHIỀU TÁC GIẢ 2019 Elementary & Early Years EVERYWHERE YOU GO Director HUYEN NGUYEN Managing Director JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] Managing Editor & CHRISTINE VAN Art Director [email protected] Online Editor JAMES PHAM [email protected] This Month’s Cover Staff Photographer VY LAM [email protected] Model: Lily Rivero from Victory MMA International (An Loc 1 Graphic Designer LAM SON VU Building, Floor 15, Street 15, An [email protected] Phu, D2) For advertising, please contact: ƠI VIỆT NAM - Art (Nghệ thuật) NHIỀU TÁC GIẢ English 0948 779 219 Ngôn ngữ: tiếng Việt - Anh Vietnamese 0932 164 629 NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH NIÊN 64 Bà Triệu - Hoàn Kiếm - Hà Nội ĐT (84.04) 39424044-62631719 Fax: 04.39436024. Website: nxbthanhnien.vn Email: [email protected] Chi nhánh: 27B Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Phường Đa Kao, Quận 1, TP. Hồ Chí Minh ĐT: (08) 62907317 Chịu trách nhiệm xuất bản: Giám đốc, Tổng biên tập Nguyễn Xuân Trường Biên tập: Tạ Quang Huy Thực hiện liên kết xuất bản: Cty TNHH Truyền thông và Quảng cáo Ơi Việt Nam 14 D1 Đường Thảo Điền, Phường Thảo Điền, Quận 2, TP. Hồ Chí Minh Số lượng 6000 cuốn, khổ 21cm x 29,7cm Đăng ký KHXB: 1165/CXBIPH/36-49/TN QĐXB số: 807/QĐ - TN ISBN số: 978-604-966-720-6 Chế bản và in tại General [email protected]