The Legionella Type II Secretion Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legionnaires' Disease, Pontiac Fever, Legionellosis and Legionella

Legionnaires’ Disease, Pontiac Fever, Legionellosis and Legionella Q: What is Legionellosis and who is at risk? Legionellosis is an infection caused by Legionella bacteria. Legionellosis can present as two distinct illnesses: Pontiac fever (a self-limited flu-like mild respiratory illness), and Legionnaires’ Disease (a more severe illness involving pneumonia). People of any age can get Legionellosis, but the disease occurs most frequently in persons over 50 years of age. The disease most often affects those who smoke heavily, have chronic lung disease, or have underlying medical conditions that lower their immune system, such as diabetes, cancer, or renal dysfunction. Persons taking certain drugs that lower their immune system, such as steroids, have an increased risk of being affected by Legionellosis. Many people may be infected with Legionella bacteria without developing any symptoms, and others may be treated without having to be hospitalized. Q: What is Legionella? Legionella bacteria are found naturally in freshwater environments such as creeks, ponds and lakes, as well as manmade structures such as plumbing systems and cooling towers. Legionella can multiply in warm water (77°F to 113°F). Legionella pneumophila is responsible for over 90 percent of Legionnaires’ Disease cases and several different species of Legionella are responsible for Pontiac Fever. Q: How is Legionella spread and how does someone acquire Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ Disease/Pontiac Fever)? Legionella bacteria become a health concern when they grow and spread in manmade structures such as plumbing systems, hot water tanks, cooling towers, hot tubs, decorative fountains, showers and faucets. Legionellosis is acquired after inhaling mists from a contaminated water source containing Legionella bacteria. -

Metaproteogenomic Insights Beyond Bacterial Response to Naphthalene

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISME Journal – Original article Metaproteogenomic insights beyond bacterial response to 5 naphthalene exposure and bio-stimulation María-Eugenia Guazzaroni, Florian-Alexander Herbst, Iván Lores, Javier Tamames, Ana Isabel Peláez, Nieves López-Cortés, María Alcaide, Mercedes V. del Pozo, José María Vieites, Martin von Bergen, José Luis R. Gallego, Rafael Bargiela, Arantxa López-López, Dietmar H. Pieper, Ramón Rosselló-Móra, Jesús Sánchez, Jana Seifert and Manuel Ferrer 10 Supporting Online Material includes Text (Supporting Materials and Methods) Tables S1 to S9 Figures S1 to S7 1 SUPPORTING TEXT Supporting Materials and Methods Soil characterisation Soil pH was measured in a suspension of soil and water (1:2.5) with a glass electrode, and 5 electrical conductivity was measured in the same extract (diluted 1:5). Primary soil characteristics were determined using standard techniques, such as dichromate oxidation (organic matter content), the Kjeldahl method (nitrogen content), the Olsen method (phosphorus content) and a Bernard calcimeter (carbonate content). The Bouyoucos Densimetry method was used to establish textural data. Exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg, K and 10 Na) extracted with 1 M NH 4Cl and exchangeable aluminium extracted with 1 M KCl were determined using atomic absorption/emission spectrophotometry with an AA200 PerkinElmer analyser. The effective cation exchange capacity (ECEC) was calculated as the sum of the values of the last two measurements (sum of the exchangeable cations and the exchangeable Al). Analyses were performed immediately after sampling. 15 Hydrocarbon analysis Extraction (5 g of sample N and Nbs) was performed with dichloromethane:acetone (1:1) using a Soxtherm extraction apparatus (Gerhardt GmbH & Co. -

BD-CS-057, REV 0 | AUGUST 2017 | Page 1

EXPLIFY RESPIRATORY PATHOGENS BY NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING Limitations Negative results do not rule out viral, bacterial, or fungal infections. Targeted, PCR-based tests are generally more sensitive and are preferred when specific pathogens are suspected, especially for DNA viruses (Adenovirus, CMV, HHV6, HSV, and VZV), mycobacteria, and fungi. The analytical sensitivity of this test depends on the cellularity of the sample and the concentration of all microbes present. Analytical sensitivity is assessed using Internal Controls that are added to each sample. Sequencing data for Internal Controls is quantified. Samples with Internal Control values below the validated minimum may have reduced analytical sensitivity or contain inhibitors and are reported as ‘Reduced Analytical Sensitivity’. Additional respiratory pathogens to those reported cannot be excluded in samples with ‘Reduced Analytical Sensitivity’. Due to the complexity of next generation sequencing methodologies, there may be a risk of false-positive results. Contamination with organisms from the upper respiratory tract during specimen collection can also occur. The detection of viral, bacterial, and fungal nucleic acid does not imply organisms causing invasive infection. Results from this test need to be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical history, results of other laboratory tests, epidemiologic information, and other available data. Confirmation of positive results by an alternate method may be indicated in select cases. Validated Organisms BACTERIA Achromobacter -

Coxiella Burnetii

SENTINEL LEVEL CLINICAL LABORATORY GUIDELINES FOR SUSPECTED AGENTS OF BIOTERRORISM AND EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES Coxiella burnetii American Society for Microbiology (ASM) Revised March 2016 For latest revision, see web site below: https://www.asm.org/Articles/Policy/Laboratory-Response-Network-LRN-Sentinel-Level-C ASM Subject Matter Expert: David Welch, Ph.D. Medical Microbiology Consulting Dallas, TX [email protected] ASM Sentinel Laboratory Protocol Working Group APHL Advisory Committee Vickie Baselski, Ph.D. Barbara Robinson-Dunn, Ph.D. Patricia Blevins, MPH University of Tennessee at Department of Clinical San Antonio Metro Health Memphis Pathology District Laboratory Memphis, TN Beaumont Health System [email protected] [email protected] Royal Oak, MI BRobinson- Erin Bowles David Craft, Ph.D. [email protected] Wisconsin State Laboratory of Penn State Milton S. Hershey Hygiene Medical Center Michael A. Saubolle, Ph.D. [email protected] Hershey, PA Banner Health System [email protected] Phoenix, AZ Christopher Chadwick, MS [email protected] Association of Public Health Peter H. Gilligan, Ph.D. m Laboratories University of North Carolina [email protected] Hospitals/ Susan L. Shiflett Clinical Microbiology and Michigan Department of Mary DeMartino, BS, Immunology Labs Community Health MT(ASCP)SM Chapel Hill, NC Lansing, MI State Hygienic Laboratory at the [email protected] [email protected] University of Iowa [email protected] Larry Gray, Ph.D. Alice Weissfeld, Ph.D. TriHealth Laboratories and Microbiology Specialists Inc. Harvey Holmes, PhD University of Cincinnati College Houston, TX Centers for Disease Control and of Medicine [email protected] Prevention Cincinnati, OH om [email protected] [email protected] David Welch, Ph.D. -

Evolutionary Origin of Insect–Wolbachia Nutritional Mutualism

Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism Naruo Nikoha,1, Takahiro Hosokawab,1, Minoru Moriyamab,1, Kenshiro Oshimac, Masahira Hattoric, and Takema Fukatsub,2 aDepartment of Liberal Arts, The Open University of Japan, Chiba 261-8586, Japan; bBioproduction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tsukuba 305-8566, Japan; and cCenter for Omics and Bioinformatics, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, Kashiwa 277-8561, Japan Edited by Nancy A. Moran, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved June 3, 2014 (received for review May 20, 2014) Obligate insect–bacterium nutritional mutualism is among the insects, generally conferring negative fitness consequences to most sophisticated forms of symbiosis, wherein the host and the their hosts and often causing hosts’ reproductive aberrations to symbiont are integrated into a coherent biological entity and un- enhance their own transmission in a selfish manner (7, 8). Re- able to survive without the partnership. Originally, however, such cently, however, a Wolbachia strain associated with the bedbug obligate symbiotic bacteria must have been derived from free-living Cimex lectularius,designatedaswCle, was shown to be es- bacteria. How highly specialized obligate mutualisms have arisen sential for normal growth and reproduction of the blood- from less specialized associations is of interest. Here we address this sucking insect host via provisioning of B vitamins (9). Hence, it –Wolbachia evolutionary -

Legionella Shows a Diverse Secondary Metabolism Dependent on a Broad Spectrum Sfp-Type Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase

Legionella shows a diverse secondary metabolism dependent on a broad spectrum Sfp-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase Nicholas J. Tobias1, Tilman Ahrendt1, Ursula Schell2, Melissa Miltenberger1, Hubert Hilbi2,3 and Helge B. Bode1,4 1 Fachbereich Biowissenschaften, Merck Stiftungsprofessur fu¨r Molekulare Biotechnologie, Goethe Universita¨t, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2 Max von Pettenkofer Institute, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨tMu¨nchen, Munich, Germany 3 Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Zu¨rich, Zu¨rich, Switzerland 4 Buchmann Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Goethe Universita¨t, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT Several members of the genus Legionella cause Legionnaires’ disease, a potentially debilitating form of pneumonia. Studies frequently focus on the abundant number of virulence factors present in this genus. However, what is often overlooked is the role of secondary metabolites from Legionella. Following whole genome sequencing, we assembled and annotated the Legionella parisiensis DSM 19216 genome. Together with 14 other members of the Legionella, we performed comparative genomics and analysed the secondary metabolite potential of each strain. We found that Legionella contains a huge variety of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that are potentially making a significant number of novel natural products with undefined function. Surprisingly, only a single Sfp-like phosphopantetheinyl transferase is found in all Legionella strains analyzed that might be responsible for the activation of all carrier proteins in primary (fatty acid biosynthesis) and secondary metabolism (polyketide and non-ribosomal peptide synthesis). Using conserved active site motifs, we predict Submitted 29 June 2016 some novel compounds that are probably involved in cell-cell communication, Accepted 25 October 2016 Published 24 November 2016 differing to known communication systems. -

Burkholderia Cenocepacia Intracellular Activation of the Pyrin

Activation of the Pyrin Inflammasome by Intracellular Burkholderia cenocepacia Mikhail A. Gavrilin, Dalia H. A. Abdelaziz, Mahmoud Mostafa, Basant A. Abdulrahman, Jaykumar Grandhi, This information is current as Anwari Akhter, Arwa Abu Khweek, Daniel F. Aubert, of September 29, 2021. Miguel A. Valvano, Mark D. Wewers and Amal O. Amer J Immunol 2012; 188:3469-3477; Prepublished online 24 February 2012; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102272 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/7/3469 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2012/02/24/jimmunol.110227 Material 2.DC1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 71 articles, 17 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/7/3469.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 29, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2012 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Activation of the Pyrin Inflammasome by Intracellular Burkholderia cenocepacia Mikhail A. -

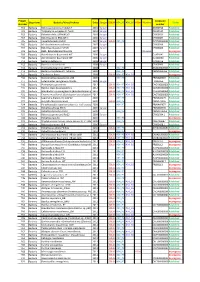

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Choline Supplementation Sensitizes Legionella Dumoffii to Galleria

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Choline Supplementation Sensitizes Legionella dumoffii to Galleria mellonella Apolipophorin III 1, , 2, 3 Marta Palusi ´nska-Szysz * y , Agnieszka Zdybicka-Barabas y , Rafał Luchowski , Emilia Reszczy ´nska 4, Justyna Smiałek´ 5 , Paweł Mak 5 , Wiesław I. Gruszecki 3 and Małgorzata Cytry ´nska 2 1 Department of Genetics and Microbiology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Akademicka St. 19, 20-033 Lublin, Poland 2 Department of Immunobiology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Akademicka St. 19, 20-033 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.Z.-B.); [email protected] (M.C.) 3 Department of Biophysics, Institute of Physics, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Computer Science, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Maria Curie-Sklodowska Square 1, 20-031 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (W.I.G.) 4 Department of Plant Physiology and Biophysics, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Akademicka St. 19, 20-033 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Analytical Biochemistry, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 7 St., 30-387 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] (J.S.);´ [email protected] (P.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to the work. y Received: 15 June 2020; Accepted: 11 August 2020; Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract: The growth of Legionella dumoffii can be inhibited by Galleria mellonella apolipophorin III (apoLp-III) which is an insect homologue of human apolipoprotein E., and choline-cultured L. -

Mariem Joan Wasan Oloroso

Interactions between Arcobacter butzleri and free-living protozoa in the context of sewage & wastewater treatment by Mariem Joan Wasan Oloroso A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Health Sciences School of Public Health University of Alberta © Mariem Joan Wasan Oloroso, 2021 Abstract Water reuse is increasingly becoming implemented as a sustainable water management strategy in areas around the world facing freshwater shortages and nutrient discharge limits. However, there are a host of biological hazards that must be assessed prior to and following the introduction of water reuse schemes. Members of the genus Arcobacter are close relatives to the well-known foodborne campylobacter pathogens and are increasingly being recognized as emerging human pathogens of concern. Arcobacters are prevalent in numerous water environments due to their ability to survive in a wide range of conditions. They are particularly abundant in raw sewage and are able to survive wastewater treatment and disinfection processes, which marks this genus as a potential pathogen of concern for water quality. Because the low levels of Arcobacter excreted by humans do not correlate with the high levels of Arcobacter spp. present in raw sewage, it was hypothesised that other microorganisms in sewage may amplify the growth of Arcobacter species. There is evidence that Arcobacter spp. survive both within and on the surface of free-living protozoa (FLP). As such, this thesis investigated the idea that Arcobacter spp. may be growing within free-living protozoa also prevalent in raw sewage and providing them with protection during treatment and disinfection processes. -

Host-Adaptation in Legionellales Is 2.4 Ga, Coincident with Eukaryogenesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/852004; this version posted February 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Host-adaptation in Legionellales is 2.4 Ga, 2 coincident with eukaryogenesis 3 4 5 Eric Hugoson1,2, Tea Ammunét1 †, and Lionel Guy1* 6 7 1 Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Science for Life Laboratories, 8 Uppsala University, Box 582, 75123 Uppsala, Sweden 9 2 Department of Microbial Population Biology, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary 10 Biology, D-24306 Plön, Germany 11 † current address: Medical Bioinformatics Centre, Turku Bioscience, University of Turku, 12 Tykistökatu 6A, 20520 Turku, Finland 13 * corresponding author 14 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/852004; this version posted February 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 15 Abstract 16 Bacteria adapting to living in a host cell caused the most salient events in the evolution of 17 eukaryotes, namely the seminal fusion with an archaeon 1, and the emergence of both the 18 mitochondrion and the chloroplast 2. A bacterial clade that may hold the key to understanding 19 these events is the deep-branching gammaproteobacterial order Legionellales – containing 20 among others Coxiella and Legionella – of which all known members grow inside eukaryotic 21 cells 3. -

Project Number Organisms Bacteria/Virus/Archaea Date

Project_ Accession Organisms Bacteria/Virus/Archaea Date Sanger SOLiD 454_PE 454_SG PGM Illumina Status Number number P01 Bacteria Rickettsia conorii str.Malish 7 2001 Sanger AE006914 Published P02 Bacteria Tropheryma whipplei str.Twist 2003 Sanger AE014184 Published P03 Bacteria Rickettsia felis URRWXCal2 2005 Sanger CP000053 Published P04 Bacteria Rickettsia bellii RML369-C 2006 Sanger CP000087 Published P05 Bacteria Coxiella burnetii CB109 2007 Sanger SOLiD 454_PE AKYP00000000 Published P06 Bacteria Minibacterium massiliensis 2007 Sanger CP000269 Published P07 Bacteria Rickettsia massiliae MTU5 2007 Sanger CP000683 Published P08 Bacteria BaBL=Bête à Bernard Lascola 2007 Illumina In progress P09 Bacteria Acinetobacter baumannii AYE 2006 Sanger CU459141 Published P10 Bacteria Acinetobacter baumannii SDF 2006 Sanger CU468230 Published P11 Bacteria Borrelia duttonii Ly 2008 Sanger CP000976 Published P12 Bacteria Borrelia recurrentis A1 2008 Sanger CP000993 Published P13 Bacteria Francisella tularensis URFT1 2008 454_PE ABAZ00000000Published P14 Bacteria Borrelia crocidurae str. Achema 2009 454_PE PRJNA162335 Published P15 Bacteria Citrobacter koseri 2009 SOLiD 454_PE 454_SG In progress P16 Bacteria Diplorickettsia massiliensis 20B 2009 454_PE PRJNA86907 Published P17 Bacteria Enterobacter aerogenes EA1509E 2009 Sanger FO203355 Published P18 Bacteria Actinomyces grossensis 2012 SOLiD 454_PE 454_SG CAGY00000000Published P19 Bacteria Bacillus massiliosenegalensis 2012 SOLiD 454_PE 454_SG CAHJ00000000 Published P20 Bacteria Brevibacterium senegalensis