The Ritual of the Runway: Studying Social Order and Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINDY CITY TIMES' 2014 Week One Of

ICONIC AUTHOR FELICE PICANO WINDY CITY PAGE 22 THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 NOV. 26, 2014 VOL 30, NO. 9 TIMESwww.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Having HIV/AIDS: Fighting stigma TRANSGENDER BY LAWRENCE FERBER DAY OF REMEMBRANCE Stigma: a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person EVENTS PAGEs 8-9 Hearing the words “I’m HIV-positive” made Bryan* (names and some details have been changed) freeze. A 23-year-old graphic designer, Bryan had met a guy at a Boystown gay club, a svelte 25-year-old tourist, Zach, with whom he danced, drank and laughed. Around 1 a.m., just before heading to Zach’s hotel for more private activities together, Zach disclosed his positive HIV status. His viral load was undetectable—successfully sup- pressed with a drug regimen to the point it was low to no risk for transmission; also, he was clear of other STDs and he packed an ample supply of condoms. Howard Brown Bryan declined to go back with him, though, offering a politely worded excuse Health Center CEO rather than saying what he really thought: “I don’t sleep with HIV-positive guys.” David E. Munar. Photo by Turn to page 6 Andrew Collings COALITION EXPLORING WINDY CITY TIMES’ 2014 STORAGE ISSUES FOR HOMELESS YOUTH week one of two PAGE 10 HOLIDAY pages 23-26 GIFT GUIDE windy city Queercast— AND HOST AMY matheny—marK show #600 PAGE 22 2 Nov. 26, 2014 WINDY CITY TIMES A STARMAN HAS LANDED IN CHICAGO GET YOUR TICKETS BEFORE HE’S GO NE For extended hours and tickets, visit mcachicago.org/bowie Closes Jan 4 Presented by Thompson Chicago, MCA Chicago’s Exclusive Hotel Partner Exhibition organized by the Victoria and Albert Sound experience by Museum, London David Bowie, 1973. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

AP Human Geography Summer Assignment

AP Human Geography Summer Assignment Taking You Places Introduction Congratulations on your decision to take AP Human Geography. Geography is an exciting subject and completing this class will help youfind success during the rest of your high school career. In AP Human Geography you will learn to make connections and ask questions in all of your other classes. You will establish the study habits and the dicipline needed to suceed in upper level courses. A basic knowledge of Geography will help you understand the way the world around you works and help you spot opportunities for success. This Summer Assignment has been created to help you prepare for the year ahead by giving you a chance to view the world through a Geographers perspective or lens. It will serve as several important grades when you start the year. It is important that you invest the time to work on this assignment because you will not be able to complete it overnight. You can choose to complete the activites in any order you wish, they will all help you prepare for the course. Remember, Geography can take you far! AP Human Geography World Regions: A Closer Look World regions maps: Many of the regions overlap or have treansitional boundaries, such as Brazil, which is part of Latin America, but has Portuguese colonial heritage. Although some regions are based on culture, others are defined by physigraphic features, such as sub-Saharan Africa, which is the part of the continent south of the Sahara Desert. Not all geographers agree on how each region is defined. -

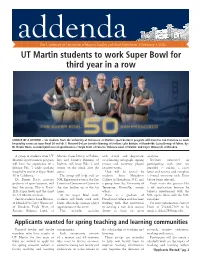

UT Martin Students to Work Super Bowl for Third Year in a Row

addenda The University of Tennessee at Martin Faculty and Staff Newsletter | February 1, 2016 UT Martin students to work Super Bowl for third year in a row CHANCE OF A LIFETIME – Six students from the University of Tennessee at Martin’s sport business program will travel to San Francisco to work hospitality events at Super Bowl 50 on Feb. 7. Pictured (l-r) are Jennifer Dinning, of Joelton; Luke Brittain, of Humboldt; Casey Dowty, of Fulton, Ky.; Dr. Dexter Davis, assistant professor of sport business; Twyla Pratt, of Parsons; Rebecca Lund, of Martin; and Cayce Wainscott, of Dresden. A group of students from UT Martin; Casey Dowty, of Fulton, with arrival and departure, analytics. Martin’s sport business program Ky.; and Jennifer Dinning, of coordinating autograph signing Students interested in will have the experience of a Joelton, will leave Feb. 2 and venues and escorting players participating each year are lifetime Feb. 7 while working return on the ninth after the between events. required to submit a cover hospitality events at Super Bowl game. They will be joined by letter and resume and complete 50 in California. The group will help staff an students from Houghton a formal interview with Davis Dr. Dexter Davis, assistant NFL Experience event at the San College in Houghton, N.Y., and before being selected. professor of sport business, will Francisco Convention Center in a group from the University of Davis treats the process like lead the group. This is Davis’ the days leading up to the big Tennessee, Knoxville, among a job application because he 11th Super Bowl and the third game. -

The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Announces 2010/11 Season

MAY 14, 2010 The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Announces 2010/11 Season Highlights include: Theatre season focuses on works by Irish playwrights and features performances by The Druid Theatre of Galway in The Cripple of Inishmaan and the Abbey Theatre in Terminus Other theatre highlights include Tectonic Theatre Project’s The Laramie Residency and Ella The Musical, a bio-musical about the celebrated vocalist Ella Fitzgerald Dance Celebration season, co-presented by Dance Affiliates and the Annenberg Center, juxtaposes blockbuster dance companies with emerging talent New works by Paul Taylor, Pilobolus and Parsons Dance Companies; Philadelphia debuts by up and coming choreographers Aszure Barton and Larry Keigwin Trumpet player and composer Terence Blanchard headlines the Jazz series with a performance from his Grammy® award-winning album A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina) Philadelphia native Christian McBride, jazz vocalist Nnenna Freelon and The Preservation Hall Jazz Band also perform as part of Jazz season Partnership with the Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (PIFA) brings performances of famed puppeteer Basil Twist’s Petrushka to the Annenberg Center stage African Roots Series features the legendary Hugh Masekela, South African vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and a Gospel performance by Take 6 Irish Roots Series celebrates the 25th anniversary of Altan; other highlights include Eileen Ivers & Immigrant Soul, Irish holiday performance by Slide (Ireland) and singer/guitarist Kathy Mattea By Local Series continues commitment to showcase the best of Philadelphia talent – more – Page 2 Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Announces 2010/11 Season (Philadelphia, May 14, 2010) — The 2010/11 season at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts features six distinct performance series that highlight amazing artists and extraordinary experiences. -

Shaping Embodiment in the Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture

SHAPING EMBODIMENT IN THE SWAN: FAN AND BLOG DISCOURSES IN MAKEOVER CULTURE by Beth Ann Pentney M.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2003 B.A. (Hons.), Laurentian University, 2002 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Beth Ann Pentney 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Beth Ann Pentney Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Shaping Embodiment in The Swan: Fan and Blog Discourses in Makeover Culture Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lara Campbell Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Helen Hok-Sze Leung Senior Supervisor Associate Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Mary Lynn Stewart Supervisor Professor ______________________________________ Dr. Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Zoë Druick Internal Examiner Associate Professor, School of Communication ______________________________________ Dr. Cressida Heyes External Examiner Professor, Philosophy University of Alberta Date Defended/Approved: ______________________________________ ii Partial Copyright Licence Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. -

Asian Americans and the Cultural Economy of Fashion / Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu

UIF #&"65*'6-HFOFSBUJPO UIF #&"65*'6-HFOFSBUJPO >PF>K>JBOF@>KP BOEUIF @RIQRO>IB@LKLJV PGC>PEFLK 5IVZ-JOI/HVZFO5V ARHBRKFSBOPFQVMOBPP AROE>J>KAILKALK ∫ 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. To my mother CONTENTS acknowledgments ix introduction Fashion, Free Trade, and the ‘‘Rise of the Asian Designer’’ 1 Part I 1. Crossing the Assembly Line: Skills, Knowledge, and the Borders of Fashion 31 2. All in the Family? Kin, Gifts, and the Networks of Fashion 63 Part II 3. The Cultural Economy of Asian Chic 99 4. ‘‘Material Mao’’: Fashioning Histories Out of Icons 133 5. Asia on My Mind: Transnational Intimacies and Cultural Genealogies 169 epilogue 203 notes 209 bibliography 239 index 253 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book would not have been possible without the time, energy, and imagination of many friends, colleagues, and kind strangers. It is a pleasure to be able to acknowledge them here. I want to begin by thanking all the designers who allowed me to talk with them, hang around their shops, and learn from them. Knowing what I now know about the demands of their work, I am even more amazed that they could find so much time for me. Without their generosity, I would not have this story to tell. The seeds of this book were planted many years ago, but they really grew in conversation with the wonderful colleagues, at di√er- ent institutions, who have read, heard, or talked about these ideas with me, including Christine Balance, Luz Calvo, Derek Chang, Beth Coleman, Iftikhar Dadi, Maria Fernandez, Wen Jin, James Kim, Nhi Lieu, Christina Moon, Viranjini Munsinghe, Mimi Ngu- yen and Minh-Ha Pham (and their spot-on blog, Threadbared), Je√rey Santa Anna, Barry Shank, Julie Sze, Elda Tsou, K. -

Series 400 of Quilting Arts TV Has Just Begun Airing Nationwide and You

Series 400 of Quilting Arts TV has just begun airing nationwide and you won’t want to miss it! With its fresh and contemporary perspective on quilting, it was a natural fit for BERNINA of America to become the official sewing machine sponsor. And what’s really exciting is to watch the BERNINA 830 in action on the show! “I have to say I have been a BERNINA fan ever since I started quilting, and I was thrilled to learn that they were coming on board as the official sewing machine sponsor of Quilting Arts TV!” says host Pokey Bolton. “I also have a BERNINA in my home studio. Not only is it a sturdy machine with some pretty incredible engineering, it’s reliable, easy- to-use, and yields beautiful results.” In this season, host Pokey Bolton (editor-in-chief of Quilting Arts Magazine®) and the guests of Quilting Arts TV explore numerous contemporary quilting topics, such as art quilt design, free-motion quilting, thread painting, fabric manipulation, and more. Create inspiring projects like fabric portraits, journal quilts, patchwork totes, and even meet a very special guest—Project Runway’s first season’s winner, Jay McCarroll. Want to know where Quilting Arts TV is airing in your area? Visit http://www.quiltingartstv.com, click on the station finder, then enter your zip code to find the time and station in your area. If it’s not airing in your area, you can help bring Quilting Arts TV to your local station by emailing or writing your local PBS station. (Tips and instructions on how to do so are included on the quiltingartstv.com website.) Want even more ideas for fresh and contemporary quilt designs? Visit the new Quilting Arts online community! We’d like to extend a special offer to the BERNINA community of sewers and quilters by offering you a FREE eBook - Seven Quilted Bag Patterns: Handmade Quilt Bags from Quilting Arts http://www.quiltingarts.com/7-Free-Quilted-Bag- Patterns. -

Rektorer Protesterar Mot Sparkrav I Skolan

24 JULI 2007 ÅRG 18, NR 30 Sommarupplaga +7.700 ex Nu 74.500 ex! Besöksadress Värmdövägen 205, Nacka Red 555 266 20, [email protected] Annons 555 266 10 nvp.se NYHETER 10 TEST 12-13 NYHETER 7 KRÖNIKA 10 ”Busschauffören NVP testar Cillas badstig ”Fel klädd för att räddade mitt liv” turistslingan blev en väg träffa drömtjejen” Språkresan blev Rektorer protesterar en mardröm VÄRMDÖ Tre unga Värm- dötjejers språkresa till Brigh- ton i England blev inte vad de tänkt sig. Värdfamiljen gav dem väldigt lite mat och mot sparkrav i skolan de var berusade och bråkade varje dag. Efter en tvist i All- VÄRMDÖ 19 miljoner. Så mycket ska Värmdös gemensamt protestbrev, säger ”går till historien männa reklamationsnämn- grundskolor spara de kommande tre åren. Nu har som det största som någonsin presenterats av po- den får flickorna nu rätt till prisavdrag. ➤ rektorerna fått nog av det sparkrav som man, i ett litikerna i kommunen”. 8 ➤ 8 Ö sökes till konstprojekt NACKA/VÄRMDÖ Nästa sommar planerar några ös- terikiska performanceartis- ter ett konstprojekt på en ö. Nu undrar föreningen ”Mossutställningen” om det är någon som har en ö att låna ut. ➤ 15 SPORTEN Silver i Gothia Cup för Boo FF NACKA FOTBOLL Boo FF:s elvaåriga pojkar lyckades med bedriften att sluta på en andra plats i den prestigefulla turneringen Gothia Cup i Göteborg. La- get spelade jättebra och för- lorade en tät match i finalen mot Werder Bremens ut- vecklingslag. ➤ 21 Gabriel är Värmdös egen allsångskung FOTO: JENNY FRJING SIGGESTA När han inte leder 900 gospelsångare i kyrkan, 3 000 ungar i Himmelstalundshallen eller förfest i SVT, står han varje måndagkväll i juli på scenen i logen på Siggesta. -

Advanced Sculpture Students “De-Disneyfy” Fairy Tales Through Couture Costume Millinery

Advanced Sculpture Students “De-Disneyfy” Fairy Tales through Couture Costume Millinery Liz Terlecki Introduction I am often aghast when students exhibit baffled looks at the mention of what I consider to be Blockbuster movies like Edward Scissorhands or Ghostbusters. Typically, the movies we all assume that everyone has seen are films that conjure only a few raised student hands verifying a one-time screening, or at least familiarity, with the movie. However, it rarely fails that Disney movies are those with which most students are not only familiar, but also well versed. This past year, Disney’s hit Frozen has all but taken over the world of animated films (and all merchandise born thereto) and now seems to dominate pop culture categories of “most watched” and “most referenced.” The fact that my students are teenagers in high school is certainly no exception to the rule, especially since cartoons like Adventure Time, Spongebob Squarepants, and even My Little Pony have begun to invade older age groups. Unfortunately, just as my students are mystified by references to the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, so are they to the real stories that inspired many Disney classics. Just when I begin thinking that I do not have much in common with this generation of teenagers, I find myself admitting that prior to writing this unit, I, too, was unfamiliar with many of the real fairy tales that influence Disney films. I was surprised by the unexpected components of death and even gore—elements with which my students are all too familiar (and attracted to) considering the recent rising popularity of zombie and vampire television shows and teenagers’ inevitable natural draw to cheesy horror flicks. -

Aids Walk Philly & Aids Run Philly to Raise

For Press Information ONLY: Cari Feiler Bender, Relief Communications, LLC 610-527-7673 or [email protected] AIDS WALK PHILLY & AIDS RUN PHILLY TO RAISE FUNDS, AWARENESS 25 th Annual Event Continues the Fight for HIV/AIDS in Philadelphia Region PHILADELPHIA – September 7, 2011 − For 25 years, AIDS Walk Philly has raised funds for HIV/AIDS service organizations in the Greater Philadelphia Region, and on Sunday, October 16, 2011, the 25th Annual AIDS Walk Philly & AIDS Run Philly presented by Merck continues the fight. One in five Americans infected with HIV don’t know it. Philadelphians can make a difference in the fight against HIV and AIDS by participating in AIDS Walk Philly, which will bring together nearly 15,000 people to raise money for HIV prevention education, public awareness, and HIV care services here in the Greater Philadelphia region. Walk and run beginning at the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Run along the certified 5K route on Martin Luther King Drive at 8am. Walk along the 12K route, beginning along Kelly Drive at 9am and returning on Martin Luther King Drive. Right in our own backyard, thirty thousand of our friends, family, and neighbors live with HIV, a condition for which they are often judged and misunderstood. In 15 years, the rate of infection has not decreased. The 25 th Annual AIDS Walk Philly will also be a time to reflect over the past 25 years of the fundraising event as well as 30 years that the epidemic has existed. Robb Reichard, Executive Director of AIDS Fund , explains that part of the mission of the Walk is to give Philadelphians a better understanding of current HIV/AIDS facts. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M.