Florida Scrub-Jay Forages on Back of White-Tailed Deer’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Damage to Pistachios

The extent of damage to pistachios by some birds that knock nuts to the ground, where they hull, shell, and eat them, can be measured. Losses to birds that pluck nuts from the tree and fly off to eat them else- where can only be estimated. counties to the south. District I1 (Central) is Merced, Madera, Fresno, and Kings Bird damage to nistachios counties. District I11 (Northern) is Monte- rey, San Benito, Inyo, and all counties to the north of Merced County. Terrell P. Salmon 0 A. Charles Crabb 0 RexE.Marsh Scope of the problem We received 105 responses (23 percent) from the 458 surveys mailed. Thirteen (12.7 percent) were excluded from analy- Crows are the primary culprits sis, because the orchards represented followed by ravens and jays were not in production, were outside Cali- fornia, or were managed by another per- son. The remaining 92 indicated they had pistachio losses due to one or more bird species. Bird damage was widespread through- out the state, as indicated by surveys re- turned from 18 counties. These 18 coun- ties represent 98 percent of the bearing pistachio acreage in California. The infor- mation we report here is based on the sur- vey returns and does not account for bird Various bird species are pests to a step in defining the problem and evaluat- damage and control that undoubtedly oc- number of California crops. Nut crops ing current bird control methods. cur but were not reported. Our estimates such as pistachios, almonds, and walnuts The major focus of the survey was to should therefore be considered conserva- are particularly hard hit, although infor- identify the bird species involved, the ex- tive. -

A Fossil Scrub-Jay Supports a Recent Systematic Decision

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 98 Number 4 November 1996 .L The Condor 98~575-680 * +A. 0 The Cooper Omithological Society 1996 g ’ b.1 ;,. ’ ’ “I\), / *rs‘ A FOSSIL SCRUB-JAY SUPPORTS A”kECENT ’ js.< SYSTEMATIC DECISION’ . :. ” , ., f .. STEVEN D. EMSLIE : +, “, ., ! ’ Department of Sciences,Western State College,Gunnison, CO 81231, ._ e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nine fossil premaxillae and mandibles of the Florida Scrub-Jay(Aphelocoma coerulescens)are reported from a late Pliocene sinkhole deposit at Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Vertebrate biochronologyplaces the site within the latestPliocene (2.0 to 1.6 million yearsago, Ma) and more specificallyat 2.0 l-l .87 Ma. The fossilsare similar in morphology to living Florida Scrub-Jaysin showing a relatively shorter and broader bill compared to western species,a presumed derived characterfor the Florida species.The recent elevation of the Florida Scrub-Jayto speciesrank is supported by these fossils by documenting the antiquity of the speciesand its distinct bill morphology in Florida. Key words: Florida; Scrub-Jay;fossil; late Pliocene. INTRODUCTION represent the earliest fossil occurrenceof the ge- nus Aphelocomaand provide additional support Recently, the Florida Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma for the recognition ofA. coerulescensas a distinct, coerulescens) has been elevated to speciesrank endemic specieswith a long fossil history in Flor- with the Island Scrub-Jay(A. insularis) from Santa ida. This record also supports the hypothesis of Cruz Island, California, and the Western Scrub- Pitelka (195 1) that living speciesof Aphefocoma Jay (A. californica) in the western U. S. and Mex- arose in the Pliocene. ico (AOU 1995). -

Corvids of Cañada

!!! ! CORVIDS OF CAÑADA COMMON RAVEN (Corvus corax) AMERICAN CROW (Corvus brachyrhyncos) YELLOW-BILLED MAGPIE (Pica nuttalli) STELLER’S JAY (Cyanocitta stelleri) WESTERN SCRUB-JAY Aphelocoma californica) Five of the ten California birds in the Family Corvidae are represented here at the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve. Page 1 The Common Raven is the largest and can be found in the cold of the Arctic and the extreme heat of Death Valley. It has shown itself to be one of the most intelligent of all birds. It is a supreme predator and scavenger, quite sociable at certain times of the year and a devoted partner and parent with its mate. The American Crow is black, like the Raven, but noticeably smaller. Particularly in the fall, it may occur in huge foraging or roosting flocks. Crows can be a problem for farmers at times of the year and a best friend at other times, when crops are under attack from insects or when those insects are hiding in dried up leftovers such as mummified almonds. Crows know where those destructive navel orange worms are. Smaller birds do their best to harass crows because they recognize the threat they are to their eggs and young. Crows, ravens and magpies are important members of the highway clean-up crew when it comes to roadkills. The very attractive Yellow-billed Magpie tends to nest in loose colonies and forms larger flocks in late summer or fall. In the central valley of California, they can be a problem in almond and fruit orchards, but they also are adept at catching harmful insect pests. -

Collation of Brisson's Genera of Birds with Those of Linnaeus

59. 82:01 Article XXVII. COLLATION OF BRISSON'S GENERA OF BIRDS WITH THOSE OF LINNAEUS. BY J. A. ALLEN. CONTENTS. Page. Introduction ....................... 317 Brisson not greatly indebted to Linnaeus. 319 Linneus's indebtedness to Brisson .... .. ... .. 320 Brisson's methods and resources . .. 320 Brisson's genera . 322 Brisson and Linnaeus statistically compared .. .. .. 324 Brisson's 'Ornithologia' compared with the Aves of the tenth edition of Lin- naeus's 'Systema'. 325 Brisson's new genera and their Linnwan equivalents . 327 Brisson's new names for Linnaan genera . 330 Linnaean (1764 and 1766) new names for Brissonian genera . 330 Brissonian names adopted. by Linnaeus . 330 Brissonian names wrongly ascribed to other authors in Sharpe's 'Handlist of Birds'.330 The relation of six Brissonian genera to Linnlean genera . 332 Mergus Linn. and Merganser Briss. 332 Meleagris Linn. and Gallopavo Briss. 332 Alcedo Linn. and Ispida Briss... .. 332 Cotinga Briss. and Ampelis Linn. .. 333 Coracias Linn. and Galgulus Briss.. 333 Tangara Briss. and Tanagra Linn... ... 334 INTRODUCTION. In considering recently certain questions of ornithological nomenclature it became necessary to examine the works of Brisson and Linnaeus in con- siderable detail and this-examination finally led to a careful collation of Brisson's 'Ornithologia,' published in 1760, with the sixth, tenth, and twelfth editions of Linnaeus's 'Systema Naturae,' published respectively in 1748, 1758, and 1766. As every systematic ornithologist has had occasion to learn, Linnaeus's treatment of the class Aves was based on very imperfect knowledge of the suabject. As is well-known, this great systematist was primarily a botanist, secondarily a zoologist, and only incidentally a mammalogist and ornithol- ogist. -

The Chough in Britain and Ireland

The Chough in Britain and Ireland /. D. Bullock, D. R. Drewett and S. P. Mickleburgh he Chough Pyrrhocoraxpyrrhocorax has a global range that extends from Tthe Atlantic seaboard of Europe to the Himalayas. Vaurie (1959) mentioned seven subspecies and gave the range of P. p. pyrrhocorax as Britain and Ireland only. He considered the Brittany population to be the race found in the Alps, Italy and Iberia, P. p. erythroramphus, whereas Witherby et al. (1940) regarded it as the nominate race. Despite its status as a Schedule I species, and general agreement that it was formerly much more widespread, the Chough has never been adequately surveyed. Apart from isolated regional surveys (e.g. Harrop 1970, Donovan 1972), there has been only one comprehensive census, undertaken by enthusiastic volunteers in 1963 (Rolfe 1966). Although often quoted, the accuracy of the 1963 survey has remained in question, and whether the population was increasing, stable or in decline has remained a mystery. In 1982, the RSPB organised an international survey in conjunction with the IWC and the BTO, to determine the current breeding numbers and distribution in Britain and Ireland and to collect data on habitat types within the main breeding areas. A survey of the Brittany population was organised simultaneously by members of La Societe pour 1'Etude et la Protection de la Nature en Bretagne (SEPNB). The complete survey results are presented here, together with an analysis of the Chough's breeding biology based on collected data and BTO records, along with a discussion of the ecological factors affecting Choughs. Regional totals and local patterns of breeding and feeding biology are discussed in more detail in a series of regional papers for Ireland, the Isle of Man, Wales and Scotland (Bullock*/al. -

Pica Pica L.) - an Assessment with the Classification Methods

Kirazli et al.: The relationship between parental defense intensity and nest site characteristics in Eurasian magpie - 1293 - THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTAL DEFENSE INTENSITY AND NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS IN EURASIAN MAGPIE (PICA PICA L.) - AN ASSESSMENT WITH THE CLASSIFICATION METHODS KIRAZLI, C.1* – KAN KILINÇ, B.2 – YAMAÇ, E.3 1Abant İzzet Baysal University, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Sciences, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Management, 14280 Bolu, Turkey 2Anadolu University, Science Faculty, Department of Statistics, 26470 Eskişehir, Turkey e-mail: [email protected] 3Anadolu University, Science Faculty, Biology Department, 26470 Eskişehir, Turkey e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Received 16th Jan 2017; accepted 20th Mar 2017) Abstract. Nest defense behavior varies among species and depends on different factors. However little is known of the influence of urbanization and nest characteristics on the nest defense intensity as parental investment of the bird species. We observe the Eurasian magpie Pica pica nests to evaluate their nest defense behavior among those factors including urbanization degree of habitat, and nest characteristics such as nest volume, presence/absence of roof, offspring size and the number of offspring reduction for each breeding stages (incubation, early brooding and post brooding stage). To investigate the relationship between the nest defense behavior of Eurasian magpie and a set of those factors we used classification trees, binary logistic regression and random forest. According to our results nest defense strategies can be temporally changed primarily according to the nest volume with the auxiliary agents mostly a reduction of offspring number, which indicates parental capacities and offspring conditions could shape strongly their own nest defense strategies. -

A Guide to Beijing's Common Birds

A Guide To Beijing’s Common Birds The author birding in the Temple of Heaven Park, one of the best sites in central Beijing, especially during migration season. Beijing is a brilliant place to watch birds. More than 460 different types have been recorded in the Chinese capital. And, even inside the 2nd Ring Road, birds can be found! Here is a short guide to 26 of the most common birds that can be found in central Beijing’s parks and green spaces. During migration season (Spring and Autumn), many more species will be possible. 1. Eurasian Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus, 红隼) Eurasian Kestrel. Breeds in small numbers in the city. Eats small rodents (mice, voles) and small birds. Can see ultra-violet! 2. Spotted Dove (Streptopelia chinensis, 珠颈斑鸠) Spotted Dove is common in parks and gardens. Often on the ground. 3. Hoopoe (Upupa epops, 戴胜) The Hoopoe is one of Beijing’s most spectactular birds. It raises its crest when excited or alarmed. 4. Grey-capped Pygmy Woodpecker (Yungipicus canicapillus, 星头啄木鸟) Grey-capped Pygmy Woodpecker is Beijing’s smallest woodpecker. 5. Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major, 大斑啄木鸟) Great Spotted Woodpecker. Common in and around Beijing. 6. Grey-headed Woodpecker (Picus canus, 灰头绿啄木鸟) The Grey-headed Woodpecker is common in open woodland and parks. Likes to feed on the ground. Ants are its favourite food! 7. Azure-winged Magpie (Cyanopica cyanus, 灰喜鹊) The Azure-winged Magpie is sociable and often seen in small noisy flocks. 8. Red-billed Blue Magpie (Urocissa erythrorhyncha, 红嘴蓝鹊) The spectacular Red-billed Blue Magpie is a resident in some of the larger parks. -

Evolution of Corvids and Their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin

Ornis Hungarica 2020. 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin Jenő (Eugen) KESSLER Received: September 09, 2019 – Revised: February 12, 2020 – Accepted: February 18, 2020 Kessler, J. (E.) 2020. Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quater- nary in the Carpathian Basin. – Ornis Hungarica 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Abstract: Corvids are the largest songbirds in Europe. They are known in the avian fauna of Europe from the Miocene, the beginning of the Neogene, and are currently represented by 11 species. Due to their size, they occur more frequently among fossilized material than other types of songbirds, and thus have been examined to the largest extent. In the current article, we present their known evolution and their fossilized taxa in Europe and examine the osteology of extant species. Keywords: Corvidae, Neogene, Quaternary, Europe, Carpathian Basin, osteology Összefoglalás: A varjúfélék a legnagyobb termetű, Európában is elterjedt énekesmadarak. A kontinens madárfau- nájában a neogén elejétől, a miocénból ismertek, és jelenleg 11 fajjal vannak képviselve. Termetük következtében gyakrabban előfordulnak a fosszilis anyagban, mint a többi énekesmadár típus, és ennek következtében nagyobb mértékben is tanulmányozták őket. Jelen tanulmányban bemutatjuk az ismert európai evolúciójukat és fosszilis taxonjaikat, és foglalkozunk a recens fajok csonttanával is. Kulcsszavak: Corvidae, neogén, negyedidőszak, Európa, Kárpát-medence, csonttan Department of Paleontology, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/c, Hungary, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction About half of the current avian species – if not more – consists of songbirds, which are dis- tributed all around the world apart from Antarctica with a large number of specimens. -

Observations of Scrub Jays Cleaning Ectoparasites from Black-Tailed Deer

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 145 includingone inside a nestcavity. Six other islandsshowed penetrated in the present study, however, suggeststhat no indication of abnormally low nestingsuccess, and were ermine are quite capable of reaching coastal islands in probably not visited by ermine. years when their populations are high, and that such in- The major effects of ermine on guillemot breeding ap- vasionsmay be more frequent than the paucity of records pearedto be discouragementof egg-layingand a reduction suggests. of hatching successdue to nest abandonment. Many cav- ities on Black, Yellow, and Green islands which were oc- I thank W. Cairns, V. Friesen and H. Kaiser for field cupied in previous years were not used in 1983. Eggslaid assistance,and A. J. Gaston, M. B. Fenton and P. Ewins on islands where ermine presencewas confirmed or sug- for commenting on the manuscript. This study was sup- gestedwere often displacedfrom the nest cup and lacked ported by the Canadian Department of Supply and Ser- the shiny appearancewhich is normal for regularly incu- vices and the Canadian Wildlife Service. bated eggs(pers. observ.). Guillemots may have been re- LITERATURE CITED luctant to enter their nests if they had seen an ermine in the colony, which would explain the reductionin both egg- BANFIELD,A. W. F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. laying and hatching. Univ. of Toronto Press. Ermine visited islands as far as 1.6 km from the main- BIANIU,V. V. 1967. Gulls, shorebirdsand alcids of Kan- land (Pitsulak City), and may have reached Kingituayu dalaksha Bay. Israel Program for Scientific Transla- Island as well (2.2 km). -

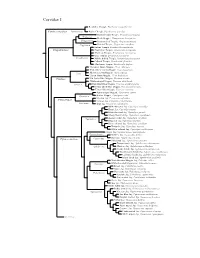

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

SE China and Tibet (Qinghai) Custom Tour: 31 May – 16 June 2013

SE China and Tibet (Qinghai) Custom Tour: 31 May – 16 June 2013 Hard to think of a better reason to visit SE China than the immaculate cream-and-golden polka- dot spotted Cabot’s Tragopan, a gorgeous serious non-disappointment of a bird. www.tropicalbirding.com The Bar-headed Goose is a spectacular waterfowl that epitomizes the Tibetan plateau. It migrates at up to 27,000 ft over the giant Asian mountains to winter on the plains of the Indian sub-continent. Tour Leader: Keith Barnes All photos taken on this tour Introduction: SE and Central China are spectacular. Both visually stunning and spiritually rich, and it is home to many scarce, seldom-seen and spectacular looking birds. With our new base in Taiwan, little custom tour junkets like this one to some of the more seldom reached and remote parts of this vast land are becoming more popular, and this trip was planned with the following main objectives in mind: (1) see the monotypic family Pink-tailed Bunting, (2) enjoy the riches of SE China in mid-summer and see as many of the endemics of that region including its slew of incredible pheasants and the summering specialties. We achieved both of these aims, including incredible views of all the endemic phasianidae that we attempted, and we also enjoyed the stunning scenery and culture that is on offer in Qinghai’s Tibet. Other major highlights on the Tibetan plateau included stellar views of breeding Pink-tailed Bunting (of the monotypic Chinese Tibetan-endemic family Urocynchramidae), great looks at Przevalski’s and Daurian Partridges, good views of the scarce Ala Shan Redstart, breeding Black-necked Crane, and a slew of wonderful waterbirds including many great looks at the iconic Bar-headed Goose and a hoarde of www.tropicalbirding.com snowfinches. -

Pellet-Casting by a Western Scrub-Jay Mary J

NOTES PELLET-CASTING BY A WESTERN SCRUB-JAY MARY J. ELPERS, Starr Ranch Bird Observatory, 100 Bell Canyon Rd., Trabuco Canyon, California 92679 (current address: 3920 Kentwood Ct., Reno, Nevada 89503); [email protected] JEFF B. KNIGHT, State of Nevada Department of Agriculture, Insect Survey and Identification, 350 Capitol Hill Ave., Reno, Nevada 89502 Pellet casting in birds of prey, particularly owls, is widely known. It is less well known that a wide array of avian species casts pellets, especially when their diets contain large amounts of arthropod exoskeletons or vertebrate bones. Currently pellet casting has been documented for some 330 species in more than 60 families (Tucker 1944, Glue 1985). Among the passerines reported to cast pellets are eight species of corvids: the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) (Lamore 1958, Tarvin and Woolfenden 1999), Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) (Balda 2002), Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) (Strickland and Ouellet 1993), Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) (Trost 1999), Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli) (Reynolds 1995), American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (Verbeek and Caffrey 2002), Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) (Butler 1974), and Common Raven (Corvus corax) (Temple 1974, Harlow et al. 1975, Stiehl and Trautwein 1991, Boarman and Heinrich 1999). However, the behavior has not been recorded in the four species of Aphelocoma jays (Curry et al. 2002, Woolfenden and Fitzpatrick 1996, Curry and Delaney 2002, Brown 1994). Here we report an observation of regurgitation of a pellet by a Western Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma californica) and describe the specimen and its contents. The Western Scrub-Jay is omnivorous and forages on a variety of arthropods as well as plant seeds and small vertebrates (Curry et al.