The Classroom and Individual Teaching Methods of Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Barcellona, Director University University

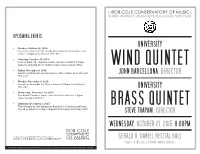

UPCOMING EVENTS UNIVERSITY • Monday, October 26, 2015: Guest Artist Recital, LSU Faculty Wind Quintet: Masterclass and Concert 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall FREE • Thursday, October 29, 2015: Concert Band: Spooktacular, Jermie Arnold, conductor 7:00pm WIND QUINTET Daniel Recital Hall $10/7; children under 13 in costume FREE • Friday, November 6, 2015: Faculty Artist Recital, John Barcellona, flute 8:00pm Daniel Recital JOHN BARCELLONA, DIRECTOR Hall $10/7 • Monday, November 9, 2015: Saxophone Ensemble, Jay Mason, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 UNIVERSITY • Wednesday, November 18, 2015: Woodwind Chamber Music, John Barcellona, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 BRASS QUINTET • Thursday, December 3, 2015: Wind Symphony and Symphonic Band, John Carnahan and Jermie Arnold, conductors 8:00pm Carpenter Performing Arts Center $10/7 STEVE TRAPANI, DIRECTOR WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2015 8:00PM For tickets please call 562.985.7000 or visit the web at: GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. PROGRAM Suite Cantabile for Woodwind Quintet .......................................Bill Douglas Sonatine .........................................................................................Eugene Bozza I. Bachianas Africanas (b. 1944) I Allegro vivo (1905-1991) II. Funk Ben Ritmico II Andante ma non troppo III. Intermezzo III Allegro vivo IV. Samba Cantando IV Largo - Allegro vivo Summer Music ............................................................................. Samuel Barber Quintet ........................................................................................ Michael Kamen (1910-1981) (1948-2003) UNIVERSITY WOODWIND QUINTET Suite Americana ........................................................................ Enrique Crespo Vanessa Fourla—flute, Spencer Klass—oboe 1. Ragtime (b. 1941) Nick Cotter—clarinet, Jennifer Ornelas—horn 3. Vals Peruano Emily Prather—bassoon 5. -

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, Jacksonville, Florida on June 13 and 14, 2018 Jeff Alford, Recording Engineer Gary Hedden, Mastering Engineer in THE SAN MARCO CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY collaboration THE LAWSON ENSEMBLE with WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1753 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2018 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. SanMarco_1753_book.indd 1-2 10/18/18 9:36 AM The Music a flute descant – commences. Five further variations ensue, each alternating characters and moods: a brisk second variation; a slow, sad, waltzing third; a short, enigmatic fourth; a sprawling fifth, this the Morning Elation for oboe and viola by Piotr Szewczyk (2010) emotional heart of the composition; and a contrapuntal sixth, which ends with a restatement of the theme Piotr Szewczyk was fairly new to Jacksonville when I asked him if he could compose an oboe/viola duo for now involving the flute. us in 2010, so I did not expect the enthusiasm and speed in which he composed “Morning Elation”! Two In all, it’s a complex, ambitious score, a glowing example of the American Romantic style of which days later he greeted me with the news that he had a burst of inspiration and composed our piece the day Beach, along with George Whitefield Chadwick, John Knowles Paine, and Arthur Foote, was such a wonder- before. -

Spring Recital Program

~PROGRAM~ 1. Sheep May Safely Graze……J.S. Bach/ Arr. Ricky Lombardo 2. Silver Celebration…………..……………..Catherine McMichael UIS Flute Choir 3. Six Studies in English Folk Song……………Vaughn Williams I. Adagio IV. Lento V. Andante tranquillo Angelina Einert, bass clarinet; Yiqing Zhu, piano 4. All of Me……………………………..John Legend and Toby Gad James Ukonu, Alexis Hogan Hobson, voices; Pamela Scott*, piano 5. String Quartet No.1…………………………Serge Rachmaninoff Romance Samantha Hwang, Natalie Kerr, violins; Savannah Brannan, viola; Kevin Loitz, cello 6. Cavatina………………………………………………John Williams 7. And I love Her…………………..John Lennon, Paul McCartney Josh Song*, guitar 8. Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso…...Camille Saint Saëns Meredith Crifasi, violin; Maryna Meshcherska, piano 9. Sweet Rain………………………………………………Bill Douglas 10. Return to Inishmore…………………………………Bill Douglas Kristin Sarvela*, oboe; Yichen Li*, piano 11. Five Hebrew Love Songs…………………………Eric Whitacre I. Temuná II. Kalá Kallá III. Lárov IV. Éyze shéleg V. Rakút Brooke Seacrist, voice and tambourine; Meredith Crifasi, violin; Yiqing Zhu, piano 12. Stereogram………………………………………….Dave Brubeck #3-For George Roberts #7-For Dave Taylor Bill Mitchell*, Bass Trombone 13. In Ireland………………………………………….Hamilton Harty Abigail Walsh*, flute; Pei-I Wang*, piano 14. Ahe Lau Makani………….Lili’uokalani, Likelike,and Kapoli; (There is a Breath) Arranged by Jerry Depuit 15. “Nachtigall, Sie Singt So Schӧn”………….Johannes Brahms Liebeslieder No. 15 Text by Georg Friedrich Daumer 16. Africa……………………………..David Paich and Jeff Porcaro -

Ordanna Matlock, Bassoon Gail Novak, Piano Kristi Hanno, Clarinet

• ordanna Matlock, bassoon Gail Novak, piano Kristi Hanno, clarinet April 23rd, 2016 at 7:30pm Recital Hall at ASU ARIZONA STATE UNIVERS I TY Antonio Lucio Vivaldi is one of the most important composers of -PROGRAM- the Baroque Era. For bassoonists, he is even more influential. Vivaldi wrote 37 bassoon concertos, more than any other composer. His incredible contributions to the bassoon repertoire makes him one of the Concerto in e minor Antonio Vivaldi few prolific composers for bassoonists. The Concerto in e minor, like I. Allegro Poco many others, was written for an orphanage of abandoned girls fNhere Vivaldi was employed as the resident musician. II. Andante Aside from his beautiful music, our historical assessment Ill. Allegro Vivaldi is full of contradictions. He was a red-haired promiscuous priest who never made it through a Mass, a world trave1,,-.. ~ho could not walk far Gail Novak, piano due to his baited breathing, and a champion of yeung female musicians. Most classical music lovers only kn ~w. him as a 'l'Usical prodigy and yet Vivaldi's life reveals a series of cht\ices ~ make us wonder who was the iThree Rainy-Day Barcarolles Evan C. Paul ' -;.,- t ._J . man behind the music. 1. A Dreary Mid-Morning r# Three RainY, !fay harcal'olles by Evan C. Paul was written in 2011. 2. A Cafe on Rue Pergol~se The p_iet e is written in three m& emetits, A Dreary Mid-Morning, A Cafe on Rue/'ergo/ese, and A Downp/Jl/r. The three movements are meant to 3. -

Stol Nyc Concerts 2006-7 Rel

As of 22 September 06, 2:16 p.m. Formatted: Border: Top: (Single solid line, Auto, 0.5 pt Line width), Bottom: (Single solid line, Auto, 0.5 pt Line width), Left: (Single solid line, Auto, 0.5 pt Line width, From text: 5 pt Border spacing: ), Right: (Single solid line, Auto, 0.5 pt Line width) PLEASE NOTE: BACKGROUND INFORMATION BEGINS ON PAGE 2 Formatted: Left: 1.08", Right: 1.25", Different first page header CLARINETIST RICHARD STOLTZMAN Formatted: Border: Box: (Single solid line, THREE NYC APPEARANCES IN 2006-07 SEASON Auto, 0.5 pt Line width) PEOPLES’ SYMPHONY CONCERTS AT WASHINGTON IRVING HIGH SCHOOL WITH THE BORROMEO STRING QUARTET SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2006, AT 8 P.M. SCHNEIDER CONCERT SERIES AT THE NEW SCHOOL AUDITORIUM WITH THE AMELIA PIANO TRIO SUNDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2006, AT 2 P.M. ZANKEL HALL AT CARNEGIE HALL WITH MIKA YOSHIDA, MARIMBA, AND FRIENDS PRESENTED BY MIDAMERICA PRODUCTIONS SUNDAY, JANUARY 28, 2007, AT 2 P.M. New York audiences have three opportunities to hear the virtuosic clarinetist Richard Stoltzman in concert. He will appear on the Peoples’ Symphony Concerts’ Chamber Series at Washington Irving High School (16th Street and Irving Place, one block east of the Union Square subway station at 14th Street) on Saturday, November 11, 2006, at 8 p.m. in performance with the Borromeo String Quartet. Tickets are $9 and can be purchased by calling, 212-586-4680 or visiting www.pscny.org. The program is as follows: Golijov - Tenebrae Shostakovich - Quartet No. 3 Brahms - Clarinet Quintet Stoltzman will also appear during the Schneider Concert Series’ 50th anniversary season at the New School’s Tishman Auditorium (66 West 12th Street) on Sunday, December 3, 2006, at 2:00 p.m. -

Woody Herman Richard Stoltzman

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Woody Herman AND THE THUNDERING HERD WITH SPECIAL GUEST STAR Richard Stoltzman FRIDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 3, 1986, AT 8:00 POWER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN Following the tradition of the Big Bands, the program is decided on rather spur-of-the-moment and pieces will be announced from the stage. The legendary Woody Herman and the Thundering Herd team up with Grammy Award-winning clarinetist Richard Stoltzman in an evening of virtuosic renditions of old jazz standards and original tunes written especially for them. Mr. Stoltzman will perform Igor Stravinsky's Ebony Concerto, a piece for swing band and clarinet composed specially for Woody, who premiered it in Carnegie Hall on March 25, 1946. WOODY HERMAN clarinet, soprano and alto sax, vocals RICHARD STOLTZMAN, clarinet Trumpets: Roger Ingram, Larry Gillcspic, Mark Lewis, Ron Stout, Bill Byrne Trombones: John Fedchock, Paul McKee, Ken Kugler Saxophones: Frank Tiberi, Dave Riekenberg, Jerry Pinter, Mike Brignola Alto sax: Keith Karabcll; Piano: Joel Weiskopf; Double bass: Dave Carpenter French horn: Daniel Facklcr; Harp: Barbara Harig; Drums: Dave Hardman The Musical Society gratefully acknowledges the generosity of Ford Motor Company Fund for underwriting the costs of this house program. New UMS 1986-87 Season Events Calendar A convenient and attractive month-by-month wall calendar for planning cultural and other important events on sale in the lobby for $4, or at Burton Tower during office hours. Third Concert of the 108th Season Sixteenth Annual Choice Series About the Artists Woodrow Charles Herman, one of the true legends of jazz and popular music, this year celebrates his 50th anniversary as a bandleader. -

Model Musician Sounds Provided By: Jim Matthews Who Are YOUR

Model Musician Sounds Provided by: Jim Matthews Who are YOUR models for music? Which performing artists do YOU listen to? Who do you play for your students as a STANDARD - model of excellence? This certainly is NOT a complete list as there are many models which are not listed. This is simply a start. Flute - Emmanuel Pahud, Andreas Blau, Sharon Bezaly, Julius Baker, Jean-Pierre Rampal, James Galway, Ian Clarke, Thomas Robertello, Mimi Stillman, Aurele Nicolet, Jasmine Choi, Paula Robison, Andrea Griminelli, Jane Rutter, Jeanne Baxtresser, Sefika Kutluer, Jazz: Hubert Laws, Nestor Torres, Greg Patillo (beatbox), Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull), Herbie Mann, Dave Valentine, Oboe - Albrecht Mayer, Marcel Tabuteau, John Mack, Joe Robinson, Alex Klein, Eugene Izotov, Heinz Holliger, Elaine Douvas, John de Lancie, Andreas Whitteman, Richard Woodhams, Ralph Gomberg, Katherine Needleman, Marc Lifschey, David Weiss, Liang Wang, Francios Leleux, Bassoon - David McGill, Arthur Grossman, Klaus Thunemann, Dag Jensen, Joseph Polisi, Frank Morrelli, Judith LeClair, Breaking Winds Bassoon Quartet, Albrecht Holder, Milan Turkovic, Gustavo Nunez, Antoine Bullant, Bill Douglas, Julie Price, Asger Svendsen, Carl Almenrader, Karen Geoghegan, Clarinet - Sabine Meyer, Julian Bliss, Andrew Mariner, Martin Frost, Larry Combs, Stanley Drucker, Alessandro Carbonare, John Manasse, Sharon Kam, Karl Leister, Ricardo Morales, Jack Brymer, Yehuda Gilad, Harold Wright, Robert Marcellus, Richard Stoltzman, Jazz: Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Paquito D’Rivera, Eddie Daniels, Pete -

DAVID FUNG, Piano Tributes: Works of Homage and Devotion

presents DAVID FUNG, piano Tributes: Works of Homage and Devotion FRI FEB 12, 7:30 PM Hodgson Concert Hall FRI FEB 12, 7:30 PM – THURS FEB 18, 7:30 PM Studio HH SUPPORTED BY MURRAY AND DORRIS TILLMAN Please silence all mobile phones and electronic devices. Photography, video and/or audio recording, and texting are forbidden during the performance. #ugapresents PROGRAM PROGRAM NOTES become (predictably) lost in distant keys. The ensuing lament is a By Luke Howard Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) passacaglia based on a descending chromatic bass line (a traditional Capriccio in B-flat Major, BWV 992, Capriccio on the departure Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) mournful motif) and in a key (F minor) of a beloved brother Capriccio in B-flat Major, BWV 992, that Bach would later associate with I. Arioso: Adagio – “Friends Gather & Try to Dissuade Him Capriccio on the departure of a grieving. The descending scales continue from departing” beloved brother as the friends are reconciled to the II. (Andante) – “They Picture the Dangers Which May Befall Him” departure, and the postillion’s horn call At some point during J. S. Bach’s late signals the arrival of the carriage. In III. Adagiosissimo – “The Friends’ Lament” teens, he wrote a poignantly evocative the final fugue—the most extended of IV. (Andante con moto) – “Since He Cannot Be Dissuaded, keyboard work, a Capriccio, in the the movements—the program seems to They Say Farewell” manner of Johann Kuhnau’s Biblical have been put aside for a demonstration which had just been published V. Allegro poco – “Aria of the Postilion” Sonatas of the teenage Bach’s precocious in 1700. -

Bill Douglas Quiet Moon - Solo Piano

Bill Douglas Quiet Moon - Solo Piano For more than three decades, Bill Douglas has been composing and performing wondrous neo-symphonic and contemporary music. His newest offering is called Quiet Moon - Solo Piano. He is a multi- instrumentalist (bassoon, piano) that crosses musical genres like the kindly winds that cross over the North American plains. Jazz, classical, and ethnic categories are definitely part of his wheelhouse. He has collaborated with master clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, played with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, released fifteen albums, and contributed to countless other albums. His music exudes gentleness, warmth, and highly listenable beauty. I first heard his music on an album called Earth Prayer back in 1999. I have been a fan ever since. Quiet Moon is a fourteen-track album of contemporary glimpses of nature, myths, and reveries. Angelico is the first track. Perhaps it is musical reflection of the beauty found in a Fra Angelico painting. The deep colors, the fine details and especially the ethereal qualities are all present in this gentle tune. Douglas’ melody is memorable and poignant and a clear welcoming to his album. Woodland Path is an unforgettable walk into the verdant forest with Bill’s inimitable sense of calmness utilizing an idyllic melody. You’re going to be a spectator to the beauty of nature in every fern, every brook, and every wildflower. Each one will have a story to tell. Bill takes on the mythological Lady of the Lake. Starting out like royal march, the song changes into ballad of long ago when kings were kind and ladies were loyal and magic was in the air. -

Richard Stoltzman

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Richard Stoltzman Clarinetist with BILL DOUGLAS, Pianist, Bassoonist, and Synthesizer JOHN PEARSON, Visual Artist and Guest Artist: EDDIE GOMEZ, Bassist THURSDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 23, 1989, AT 8:00 POWER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN "New York Counterpoint" From the artists of the best-selling "Begin Sweet World" recording and subsequent tour comes "New York Counterpoint" an evening inspired by the juxtaposition of jazz and classical music, enhanced by the visual counterpoint of images in many hues. A classical clarinetist, a composer/pianist/bassoonist, a jazz bassist, and a visual artist invite you to relax and enjoy this continuing collaboration of musical friendships, as they blend the music of J. S. Bach, Steven Reich, and Charlie Parker into "New York Counterpoint." RCA Red Seal Records Richard Stoltzman is represented by Frank Salomon Associates, New York City; Press Representatives: Gurtman & Murtha, New York City. Eddie Gomez is represented by Eric Kressman Management, New York City. Bill Douglas plays the Steinway piano available through Hammell Music, Inc. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Thirtieth Concert of the 110th Season Eighteenth Annual Choice Series About the Artists Richard Stoltzman's virtuosity, musicianship, and winning personality have catapulted him to the highest ranks of international acclaim. As soloist with more than one hundred orchestras, a recitalist and chamber music performer, and an innovative jazz artist, Stoltzman has given new meaning to the word "versatile." Stoltzman's orchestral engagements have included the Mozart, Nielsen, and Rossini concertos with the symphony orchestras of New York, Toronto, and San Francisco, and he has also performed with such orchestras as the Atlanta, Baltimore, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Montreal, Pittsburgh, and St. -

School of Music Bill Douglas (B

Gabrielle Hsu, bassoon Student Recital Series Katzin Concert Hall I March 14, 2018 I 5:00 pm Program Suite Cantando (2006) Bill Douglas I. Sambata (b. 1944) IV. Cantabile V. Bebop Capriccio Caitlin Kierum, clarinet Yiqian Song, piano Contrastes Ill ( 1977) Eugene Bozza I. Moderato (1905-1991) VIII. Allegretto VII. Allegretto Matt Fox, soprano saxophone Riptide (2009) Theresa Martin (b. 1979) Julia Lougheed, clarinet 98 Skidoo (2003) Paul Hanson (b. 1961) Evelyn Jones, bassoon Trio pour hautbois, bassoon et piano (1926) Francis Poulenc I. Presto (1899-1963) II. Andante III. Rondo Isaac Miller, oboe Yiqian Song, piano ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY School of Music Bill Douglas (b. 1944) is a Canadian composer and multi-instrumentalist. He earned a BA in music education from the University of Toronto, and master's degrees in bassoon performance and composition from Yale University. He has written many chamber works featuring the bassoon, including two Partitas for bassoon and piano, two trios for oboe, bassoon and piano, and three volumes of Eight Lyrical Pieces for bassoon and piano. Although trained as a violinist, French composer Eugene Bozza (1905-1991) is most well-known as a prolific composer of solo and chamber wind music. Two of his compositions for bassoon and piano, Recit, Sicilienne et Rondo (1935) and Fantaisie (1945) were used in the famous Paris Conservatoire concours. "He is a performer's composer, in that the music is well written for the instrument, is challenging to play and enjoyable to rehearse. He is the listener's composer since the music is always interesting, and has a familiarity of melody and tonality that even the untrained ear can enjoy." -Dr. -

Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra

JESSE AUDITORIUM SERIES Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Misha Dichter, piano; Leonard Slatkin, conductor Friday, September 28 Itzhak Perlman, violin; Samuel Sanders, piano Thursday, November 29 Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Tuesday, January 22 New York City Opera National Company, Rigoletto Sunday, March 10 Bach Aria Group Thursday, March 28 FIRST NATIONAL BANK CHAMBER MUSIC SERIES Northern Sinfonia of England, Barry Tuckwell, French horn Wednesday, October 17 Emanuel Ax, piano; Yo Yo Ma, cello Wednesday, November 7 Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Bill Douglas, piano Thursday, January 24 Ars Musica Wednesday, February 13 Beaux Arts Trio Saturday, February 23 Concord Quartet Tuesday, April 16 SPECIAL EVENTS Saint Louis Sr.mphony Pops Concert, Richard Hayman, conductor; UMC Choral Union and Patricia Miller, Artist-in-Residence Sunday, October 28 Nikolais Dance Theatre Monday, November 12 Christmas Choral Concert Messiah, Choral Union, UMC Philharmonic; Distinguished Guest Soloists and Duncan Couch, conductor Friday, December 7 and Saturday, December 8 Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Wednesday, January 23 Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Garrick Ohlsson, piano; Raphael Fruhbeck de Burgos, conductor Thursday, March 14 Houston Ballet (with orchestra) Tuesday, April 23 FIRST NATIONAL BANK MASTER CLASS SERIES Barry Tuckwell, French horn Ars Musica, Baroque music ·· To be arranged February 13 Emanual Ax, piano Beaux Arts Trio To be arranged February 23 Yo Yo Ma, cello Bach Aria Group To be arranged March 28 Richard Stoltzman, clarinet January