Seabird Rehabilitation Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petrelsrefs V1.1.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2017 & 2018 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Killian Mullarney and Tom Shevlin (www.irishbirds.ie) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.1 (August 2017). Cover Main image: Bulwer’s Petrel. At sea off Madeira, North Atlantic. 14th May 2012. Picture by Killian Mullarney. Vignette: Northern Fulmar. Great Saltee Island, Co. Wexford, Ireland. 5th May 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Antarctic Petrel [Thalassoica antarctica] 12 Beck's Petrel [Pseudobulweria becki] 18 Blue Petrel [Halobaena caerulea] 15 Bulwer's Petrel [Bulweria bulweri] 24 Cape Petrel [Daption capense] 13 Fiji Petrel [Pseudobulweria macgillivrayi] 19 Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialis] 8 Giant Petrels [Macronectes giganteus & halli] 4 Grey Petrel [Procellaria cinerea] 19 Jouanin's Petrel [Bulweria fallax] 27 Kerguelen Petrel [Aphrodroma brevirostris] 16 Mascarene Petrel [Pseudobulweria aterrima] 17 Parkinson’s Petrel [Procellaria parkinsoni] 23 Southern Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialoides] 11 Spectacled Petrel [Procellaria conspicillata] 22 Snow Petrel [Pagodroma nivea] 14 Tahiti Petrel [Pseudobulweria rostrata] 18 Westland Petrel [Procellaria westlandica] 23 White-chinned Petrel [Procellaria aequinoctialis] 20 1 Relevant Publications Beaman, M. -

BYC-08 INF J(A) ACAP: Update on the Conservation Status

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE NINTH MEETING La Jolla, California (USA) 14-18 May 2018 DOCUMENT BYC-08 INF J(a) UPDATE ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS, DISTRIBUTION AND PRIORITIES FOR ALBATROSSES AND LARGE PETRELS Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) and BirdLife International 1. STATUS AND TRENDS OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS Seabirds are amongst the most globally-threatened of all groups of birds, and conservation issues specific to albatrosses and large petrels led to drafting of the multi-lateral Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). A review of the conservation status and priorities for albatrosses and large petrels was recently published in Biological Conservation (Phillips et al. 2016). There are currently 31 species listed in Annex 1 of the Agreement. Of these, 21 (68%) are classified at risk of extinction, a stark contrast to the overall rate of 12% for the 10,694 bird species worldwide (Croxall et al. 2012, Gill & Donsker 2017). Of the 22 species of albatrosses listed by ACAP, three are listed as Critically Endangered (CR), six are Endangered (EN), six are Vulnerable (VU), six are Near Threatened (NT), and one is of Least Concern (LC). Of the nine petrel species, one is listed as CR, one as EN, four as VU, one as NT and two species as LC. The population trends of ACAP species over the last twenty years (since the mid-1990s) were re-examined in 2017 by the ACAP Population and Conservation Status Working Group (PaCSWG). Thirteen ACAP species (42%) are currently showing overall population declines. -

Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández Archipelago November 2014

Expedition Research Report Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago November 2014 Expedition Team Robert L. Flood, Angus C. Wilson, Kirk Zufelt Mike Danzenbaker, John Ryan & John Shemilt Juan Fernández Petrel KZ Stejneger’s Petrel AW First published August 2017 by www.scillypelagics.com © text: the authors © video clips: the copyright in the video clips shall remain with each individual videographer © photographs: the copyright in the photographs shall remain with each individual photographer, named in the caption of each photograph All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means – graphic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. 2 CONTENTS Report Summary 4 Introduction 4 Itinerary and Conditions 5 Bird Species Accounts 6 Summary 6 Humboldt Current and Coquimbo Bay 7 Passages Humboldt Current to Juan Fernández and return 13 At sea off the Juan Fernández archipelago 18 Ashore on Robinson Crusoe Island 26 Cetaceans and Pinnipeds 28 Acknowledgements 29 References 29 Appendix: Alpha Codes 30 White-bellied Storm-petrel JR 3 REPORT SUMMARY This report summarises our observations of seabirds seen during an expedition from Chile to the Juan Fernández archipelago and return, with six days in the Humboldt Current. Observations are summarised by marine habitat – Humboldt Current, oceanic passages between the Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago, and waters around the Juan Fernández archipelago. Also summarised are land bird observations in the Juan Fernández archipelago, and cetaceans and pinnipeds seen during the expedition. Points of interest are briefly discussed. -

Analysis of Albatross and Petrel Distribution Within the CCAMLR Convention Area: Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 13 (2006): 143–174 ANALYSIS OF ALBATROSS AND PETREL DISTRIBUTION WITHIN THE CCAMLR CONVENTION AREA: RESULTS FROM THE GLOBAL PROCELLARIIFORM TRACKING DATABASE BirdLife International (prepared by C. Small and F. Taylor) Wellbrook Court, Girton Road Cambridge CB3 0NA United Kingdom Correspondence address: BirdLife Global Seabird Programme c/o Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire SG19 2DL United Kingdom Email – [email protected] Abstract CCAMLR has implemented successful measures to reduce the incidental mortality of seabirds in most of the fisheries within its jurisdiction, and has done so through area- specific risk assessments linked to mandatory use of measures to reduce or eliminate incidental mortality, as well as through measures aimed at reducing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of albatrosses and petrels in the CCAMLR Convention Area to inform the CCAMLR risk- assessment process. Albatross and petrel distribution is analysed in terms of its division into FAO areas, subareas, divisions and subdivisions, based on remote-tracking data contributed to the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database by multiple data holders. The results highlight the importance of the Convention Area, particularly for breeding populations of wandering, grey-headed, light-mantled, black-browed and sooty albatross, and populations of northern and southern giant petrel, white-chinned petrel and short- tailed shearwater. Overall, the subareas with the highest proportion of albatross and petrel breeding distribution were Subareas 48.3 and 58.6, adjacent to the southwest Atlantic Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, but albatross and petrel breeding ranges extend across the majority of the Convention Area. -

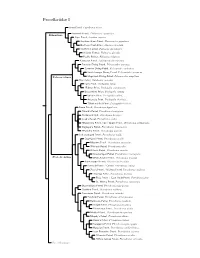

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Investigating Spatiotemporal Variation in the Diet of Westland Petrel Through

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289; this version posted August 17, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Investigating spatiotemporal variation in the diet of Westland Petrel through 2 metabarcoding, a non-invasive technique 3 Marina Querejeta1, Marie-Caroline Lefort2,3, Vincent Bretagnolle4, Stéphane Boyer1,2 4 5 6 1 Institut de Recherche sur la Biologie de l'Insecte, UMR 7261, CNRS-Université de Tours, 7 Tours, France 8 2 Environmental and Animal Sciences, Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, 9 Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 10 3 Cellule de Valorisation Pédagogique, Université de Tours, 60 rue du Plat d’Étain, 37000 11 Tours, France. 12 4 Centre d’Études Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372, CNRS & La Rochelle Université, 79360 13 Villiers en Bois, France. 14 15 16 17 18 19 Running head: Spatiotemporal variation in diet of Westland Petrel 20 21 Keywords: Conservation, metabarcoding, dietary DNA, biodiversity, New Zealand, 22 Procellaria westlandica 23 24 Abstract 25 As top predators, seabirds are in one way or another impacted by any changes in marine 26 communities, whether they are linked to climate change or caused by commercial fishing 27 activities. However, their high mobility and foraging behaviour enables them to exploit prey 28 distributed patchily in time and space. This capacity of adaptation comes to light through 29 the study of their diet. -

Fisheries Risks to the Population Viability of Black Petrel (Procellaria Parkinsoni)

Fisheries risks to the population viability of black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni) R. I. C. C. Francis1 E.A. Bell2 1NIWA Private Bag 14901 Wellington 6241 2Wildlife Management International 35 Seames Rd Rapaura RD3 Blenheim 7273 New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 51 2010 Published by Ministry of Fisheries Wellington 2010 ISSN 1176-9440 © Ministry of Fisheries 2010 Francis, R.I.C.C.; Bell, E.A. (2010). Fisheries risks to the population viability of black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni). New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 51. This series continues the Marine Biodiversity Biosecurity Report series which ceased with No. 7 in February 2005. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Francis, R.I.C.C.; Bell, E.A. (2010). Fisheries risks to the population viability of black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni). New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 51. Data on the main population of black petrel (Procellaria parkinsoni), which breeds on Great Barrier Island, were analysed. Three types of data were available. The most useful was abundance data, from which it was possible to infer that the population was probably increasing at a rate between 1.2% and 3.1% per year. Mark-recapture data were useful in estimating demographic parameters, like survival and breeding success, but contained little information on population growth rates. Fishery bycatch data from observers were too sparse and imprecise to be useful. The fact that the population is probably increasing shows that there is no evidence that fisheries currently pose a risk to this population. However, this does not imply that there is clear evidence that fisheries do not pose a risk to this population. -

Method for Mapping Matters of State Environmental Significance for the State Planning Policy 2017

Method for mapping Matters of state environmental significance For the State Planning Policy 2017 Version 6.01 Prepared by: Land Use Planning, Environment Policy and Planning, Department of Environment and Science © State of Queensland, 2020. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. Citation DES. 2020. Method for mapping Matters of state environmental significance .For the State Planning Policy 2017. -

SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE UPDATED AUGUST 2015 2 How to Use This Guide

SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE UPDATED AUGUST 2015 2 How to use this guide 1. Identify the bird • Start by looking at its bill - size and position of nostrils as shown on pages 6-9 to decide if it’s an albatross, a petrel or another group. • If it’s an albatross, use the keys and photos on pages 10-13, to identify the bird to a particular species (or to the 2 or 3 species that it might be), and go to the page specified to confirm the identification. If it’s a petrel, use the key on pages 14-15 , then go to the page as directed. If it’s a shearwater, look at pages 66-77. 2. Record Record your identification in the logbook choosing one of the FAO codes, or a combination of codes from the list on pages 96-99. 3. Take photos Take three photos of the bird as shown on pages 78-81 and submit with the logbook. 4. Sample feathers If a sampling programme is in place, pluck some feathers for DNA analysis as shown on pages 82-83. SEABIRD BYCATCH IDENTIFICATION GUIDE 3 Contents How to use this guide 2 Measuring bill and wing length 4 Albatross, Petrel or other seabird? 6 Bill guide 8 Albatross key 10 Diomedea albatross key 12 Juvenile/Immature Thalassarche key 13 Petrel key 14 North Pacific Albatrosses 16 - 21 Waved Albatross 22 Phoebetria albatrosses (light-mantled and sooty) 24 - 27 Royal albatrosses 28 - 29 ‘Wandering-type’ albatrosses 30 - 37 Thalassarche albatrosses 38 - 51 Juvenile/Immature Thalassarche albatrosses 52 - 53 Giant petrels 54 - 55 Procellaria petrels 56 - 61 Other Petrels 62 - 65 Shearwaters 66 - 77 Data collection protocols - taking photos 78 Data collection protocols - examples of photos 80 Data collection protocols - feather samples for DNA analysis 82 Leg Bands 84 References 88 Your feedback 91 Hook Removal from Seabirds 92 Albatross species list 96 Petrel and Shearwater species list 98 4 Measuring Bill & Wing Length BILL LENGTH WING LENGTH 10 20 Ruler 30 (mm) 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 200 6 Albatross, Petrel, Shearwater Albatrosses Page 10 Separate nostrils. -

List of Albatrosses and Petrel Taxa Covered by CMS and ACAP

UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Doc.16/Annex IV Order Procellariiformes - Species covered by CMS and ACAP Species currently Nomenclature Species currently listed listed under CMS according to under ACAP (Annex I) Common name (Appendix I & II)1 Dickinson 2003/052 FAMILY DIOMEDEIDAE - ALBATROSSES Diomedea exulans (II) Diomedea exulans Diomedea exulans Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans Diomedea dabbenena exulans* Tristan Albatross *Includes dabbenena Diomedea exulans Diomedea antipodensis Antipodean Albatross antipodensis Diomedea amsterdamensis Diomedea Diomedea exulans Amsterdam Albatross (I) amsterdamensis amsterdamensis Diomedea epomophora Diomedea epomophora Southern Royal Diomedea epomophora (II) epomophora Albatross Diomedea epomophora Northern Royal Diomedea sanfordi sanfordi Albatross Short Tailed Diomedea albatrus (I) Phoebastria albatrus Phoebastria albatrus Albatross Diomedea nigripes (II) Black Footed Phoebastria nigripes Phoebastria nigripes Albatross Diomedea immutabilis (II) Phoebastria immutabilis Phoebastria immutabilis Laysan Albatross Diomedea irrorata (II) Phoebastria irrorata Phoebastria irrorata Waved Albatross Diomedea cauta (II) Thalassarche cauta Thalassarche cauta Shy Albatross Thalassarche cauta White-capped Thalassarche steadi steadi Albatross Thalassarche cauta salvini and eremita are Thalassarche salvini Salvin’s Albatross salvini considered group-names Thalassarche cauta within D.cauta Thalassarche eremita Chatham Albatross eremita Diomedea bulleri (II) Thalassarche bulleri Thalassarche bulleri Buller’s Albatross Thalassarche -

Autopsy Report for Seabirds Killed and Returned from Observed New Zealand Fisheries 1 October 2008 to 30 September 2009

Autopsy report for seabirds killed and returned from observed New Zealand fisheries 1 October 2008 to 30 September 2009 D.R. Thompson DOC MARINE CONSERVATION SERVICES SERIES 6 Published by Publishing Team Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand DOC Marine Conservation Services Series is a published record of scientific research and other work conducted to guide fisheries management in New Zealand, with respect to the conservation of marine protected species. This series includes both work undertaken through the Conservation Services Programme, which is funded in part by levies on the commercial fishing industry, and Crown-funded work. For more information about DOC’s work undertaken in this area, including the Conservation Services Programme, see www.doc.govt.nz/mcs. This report is available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright December 2010, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1179–3147 (web PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–14851–0 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing by Lynette Clelland and layout by Frith Hughes. Publication was approved by the General Manager, Research and Development Group, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Methods 7 3. Results 9 3.1 Species returned 9 3.2 Target fisheries and vessels 12 3.3 Injuries of returned birds and likely cause of death 15 3.4 Body condition 17 3.5 Stomach contents 18 3.6 Seabird identification 19 4. -

Westland Petrel/Tāiko Factsheet

Westland petrel/tāiko Photo: David Hallett he survival of the Westland Fortunately the large size and aggressive nature of Westland petrels allows them to more successfully Tpetrel/tāiko has great defend themselves and their chicks against most significance as these birds are predators, enabling them to survive where other petrel species have been lost. the last remnant of a unique ecosystem. They are one of the few A late discovery petrel species that remain on the The tāiko (Procellaria westlandica) was discovered mainland of New Zealand and as recently as 1945, when pupils of Barrytown School north of Greymouth found the distinctive blackish- inhabit much of the same breeding brown bird with an ivory beak and black feet while range on the West Coast of the doing a school project. South island as they did before Staff from the National Museum (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) and the Wildlife humans arrived. Service (now the Department of Conservation) began studying the tāiko to collect information on: Numerous species of burrowing petrels once bred in • the survival rates of adult birds coastal and inland areas of both the North and South Islands. However, depredation by humans, changes • the number of chicks being produced to the habitat and predation by introduced mammals • how many birds were returning to breed. such as stoats, cats, dogs, pigs and rats have been responsible for the almost complete removal of petrels from the mainland. Since the programme began in 1969, thousands of birds have been banded in order to monitor breeding success and survival rates.