Flax and Linen: an Uncertain Oregon Industry by Steve M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raffia Palm Fibre, Composite, Ortho Unsaturated Polyester, Alkali Treatment

American Journal of Polymer Science 2014, 4(4): 117-121 DOI: 10.5923/j.ajps.20140404.03 The Effect of Alkali Treatment on the Tensile Behaviour and Hardness of Raffia Palm Fibre Reinforced Composites D. C. Anike1,*, T. U. Onuegbu1, I. M. Ogbu2, I. O. Alaekwe1 1Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria 2Department of Chemistry Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo Ebonyi State, Nigeria Abstract The effects of alkali treatment and fibre loads on the properties of raffia palm fibre polyester composite were studied. Some clean raffia palm fibres were treated with 10% NaOH, and ground. The ground treated and untreated fibres were incorporated into the ortho unsaturated polyester resin. The treated and the untreated fibre composites samples were subjected to tensile tests according to ASTM D638 using instron model 3369. The microhardness test was done by forcing a diamond cone indenter into the surface of the hard specimen, to create an indentation. The significant findings of the results showed that alkali treatment improved the microhardness and extension at break at all fibre loads, better than the untreated fibre composites, with the highest values at 20% (14.40 and 3.47mm for microhardness and extension at break respectively). Tensile strength, tensile strain and modulus of elasticity also improved for alkali treated fibre composites, except in 5% and 20% for tensile strength, 15% for tensile strain, and 15% and 20% for modulus of elasticity, compared to the corresponding fibre loads of untreated fibre composites. Keywords Raffia palm fibre, Composite, Ortho unsaturated polyester, Alkali treatment The main drawbacks of such composites are their water 1. -

Thermal Behaviour of Flax Kenaf Hybrid Natural Fiber Composite

ISSN: 2350-0328 International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 2, Issue 10 , October 2015 Thermal Behaviour of Flax Kenaf Hybrid Natural Fiber Composite V.S. Srinivasan, S. Rajendra Boopathy, B. Vijaya Ramnath Department of Mechanical Engineering, CEGC, Anna University, Chennai-25. Department of Mechanical Engineering, CEGC, Anna University, Chennai-25. Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sri Sairam Engineering College, Chennai-44. ABSTRACT: In this work, natural fibers of flax and kenaf are used. Hybrid materials are given importance as they play very important role in all applications and characterizations. This paper deals with one of such hybrid composite made of natural fibers namely, kenaf and flax fibers. The hybrid built-up is such that one layer of kenaf is sandwiched between two layers of flax fibres by hand layup method with a volume fraction of 40% using Epoxy resin and HY951 hardener. Glass fiber reinforcement polymer (GFRP) is used for lamination on both sides. Thermal properties are investigated for single fiber composites and kenaf - flax with GFRP hybrid composites. The hybrid composites have better thermal stability than single fibre composites. KEYWORDS: Flax, Kenaf, GFRP, Thermal behavior 1. INTRODUCTION The usage of natural fiber- reinforced composite materials is rapidly growing both in industries and in various research activities. The advantages of fibers are cheap, recyclable and biodegradable. Plants such as flax, hemp, cotton sisal, kenaf, banana etc., are the most used reinforcements of composites. They are used widely for manufacturing composites because of their easy availability, renewability, low density, and low price. The natural fiber containing composites are more environmental friendly and are used in transportation (automobiles, railway coaches, aerospace etc.,), military applications, building and construction industries in paneling and partition boards, packaging, consumer products etc. -

An Analysis of the Abaca Natural Fiber in Reinforcing Concrete Composites As a Construction Material in Developing Countries

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1988 An analysis of the abaca natural fiber in einforr cing concrete composites as a construction material in developing countries Rolando V. Magdamo University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1988 Rolando V. Magdamo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Construction Engineering and Management Commons, and the Materials Science and Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Magdamo, Rolando V., "An analysis of the abaca natural fiber in einforr cing concrete composites as a construction material in developing countries" (1988). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 865. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/865 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The History of Flax (Common Flax; Linum Usitatissimum)

The History of Flax (Common Flax; Linum usitatissimum) Ida Dyment http://www.flaxminnesota.com/Flax_Field_1_Med.jpg Common Flax (Linum usitatissimum) • Genus Linum, in Linaceae family. • Annual plant – grows up to 47 inches – thin leaves and stems. – Five-petal blue (to purple) flowers. http://www.mdidea.com/products/new/flax_flower01.jpg http://www.fleurdandeol.com/pic/msc/flax3.jpg The origins of Flax • Originated in the Mediterranean region into India. • Used in Egypt to wrap mummies • Early colonists grew small home plots • Began to be commercially processed starting around 1750 • Declined when cotton gin became popular Agriculture and Production • Flax grows well in temperate and sub-tropical regions in both hemisphere – France, Belgium, Russia, China, and Egypt grow a lot of the fiber flax currently – Minnesota and the Dakotas grow seed flax in the US • There are two common types of flax planted http://www.naturallygreen.co.uk/images/flaxseed.jpg Uses • Fiber – From Egypt to Modern Industry • Textiles, rope, paper • Food – Human food from seeds, fiber, oil – Livestock feed • Pharmacy – (Omega-3 fatty acids) – Heart health – skin treatment and cosmetics • Also used for ornamental purposes Omega-3 fatty acids • Omega-3 fatty acids in linseed oil may help prevent certain cancers. • Omega-3’s are also helpful for mental health • Helps lower cholesterol and regulate blood pressure • Flax also has very high level of lignans Many other uses • Flax in animal feed – Livestock and chickens • Aids digestion and • fortifies eggs • Flaxseed oil (linseed) also used for oil-painting agents, specialized paper, particleboard, varnish http://riverglenfarm.ca/__oneclick_uploads/2008/07/eggs.jpg http://www.sghongsheng.com/image/Plain%20particle%20board1.jpg http://www.frontera.com/assets/inline_images/39_braz%20cherry%20with%20linseed%20oil.jpg . -

Effect of Alkaline Treatment on Tensile Properties of Raffia Palm Fibre

Vol.5 (4), pp. 28-31, November 2018 ISSN 2354-4155 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26765/DRJEIT.2018.2598 Article Number: DRJA5731602598 Copyright © 2018 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Direct Research Journal of Engineering and Information Technology http://directresearchpublisher.org/journal/drjeit/ Research Paper Effect of Alkaline Treatment on Tensile Properties of Raffia Palm Fibre *1Uguru Hilary and 2Umurhurhu Benjamin 1Department of Agricultural and Bio-environmental Engineering Technology, Delta State Polytechnic, Ozoro, Nigeria. 2Department of Mechanical Engineering Technology, Delta State Polytechnic, Ozoro, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Received 4 October 2018; Accepted 5 November, 2018 The mechanical properties of raffia palm fibres treated with tensile properties of treated raffia fibre were better than raw sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution have been investigated in this raffia fibre. Based on the results, the tensile strength and Young study. Tensile properties (Tensile strength, Young modulus, modulus increased from 67.73 to 107.07 MPa and 1.261 to 1.406 elongation at break, tensile energy, tensile strain and yield GPa after the alkali treatment. The fibre elongation at break and strength) of the raffia palm fibres were tested under direct tension tensile energy decreased from 6.38 to 5.25 mm and 0.103 to 0.033 in a Universal Testing Machine at the crosshead speed of 5.00 Nm respectively. The results of this study are expected to be mm/min. The raffia fibres were treated with 5 percent NaOH useful in the production of composite boards and textile solution under ambient temperature for one hour. -

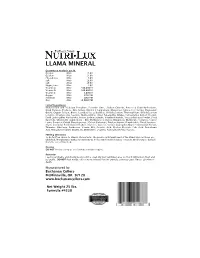

Llama Mineral

LLAMA MINERAL Guaranteed Analysis per lb. Calcium (Min) 13.0% Calcium (Max) 14.0% Phosphorus (Min) 7.0% Salt (Min) 19.0% Salt (Max) 20.0% Magnesium (Min) 2.0% Vitamin A (Min) 500,000 IU Vitamin D (Min) 160,000 IU Vitamin E (Min) 1,000 IU Copper (Min) 170 PPM Selenium (Min) 100 PPM Zinc (Min) 10,000 PPM List of Ingredients Monocalcium and Dicalcium Phosphate, Dolomite Lime, Sodium Chloride, Processed Grain By-Products, Dried Molasses Products, Zinc Sulfate, Vitamin E Supplement, Manganese Sulfate, Iron Sulfate, Magnesium Oxide, Copper Sulfate, Biotin, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium Thermophilum, Bifidobacterium Longum, Streptococcus Faecium, Maltodextrins, Dried Aspergullus Oryzae Fermentation Extract Product, Dried Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Niacin, Sodium Selinate, Vitamin A Acetate, Yucca Schidigera Powder, Dried Egg Yolk, Vitamin D3 Supplement, , Zinc Methionine Complex, Manganese Methionine Complex, Copper Lysine Complex, Cobalt Glucoheptonate, Cobalt Carbonate, Ethylenediamine Dihydriodide, Dried Saccharo- myces Cerevisiae Fermentation Product, Fructose, Glucose, Sucrose Aspergillus Niger Fermentation Extract, Thiamine, Riboflavin, Pyridoxine, Vitamin B12, Ascorbic Acid, Choline Chloride, Folic Acid, Pantothenic Acid, Menadione Sodium Bisulite, DL Methionine, L-Lysine, Natural & Artificial Flavors. Feeding Directions To be fed free choice to Llamas. Please Note: The precise nutritional need of the Llama have not been es- tablished. Manufacturer makes no warranty as to the nutritional adequacy or results which may be derived from the use of this feed. Caution DO NOT feed to sheep as this formula contains copper. Reminder Feed is perishable and should be stored in a clean dry well ventilated area so that it will remain fresh and palatable. DO NOT feed moldy, old or insect infested feed to animals as it may cause illness, abortion or death. -

Experimental Study on Flax and Sisal Hybrid Composites Reinforced with Epoxy Resin

International Journal For Technological Research In Engineering Volume 3, Issue 10, June-2016 ISSN (Online): 2347 - 4718 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY ON FLAX AND SISAL HYBRID COMPOSITES REINFORCED WITH EPOXY RESIN Santosh Madeva Naik1, Prof. Gururaja Sharma T2, Prof. Ganesh Kalagi3 1PG Student, 2Assistant Professor, School of Mechanical Engineering, REVA University, Bangalore. 3Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, SMVITM, Bantkal, Udupi. Abstract: Natural fibers have been used to reinforce II. METHDOLOGY materials for more than 200 years. The aim of this study is The methodology depicted in Figure.2 has been adopted as to evaluate mechanical properties, such as tensile, shown, fabrication and testing of composite material for compression and bending properties of hybrid sisal and flax mechanical properties in manufacturing has been selected as reinforced with epoxy resin composites. Natural fibers like a broad field of research. The composite specimen is as hemp, jute, flax, sisal and banana have the advantages fabricated according to ASTM standard. The rule of mixture that they are renewable resources and these agricultural will be calculated for each test. The various compositions are wastes can be utilized to organize fiber composites, which taken as 20% sisal fiber 5% flax fiber, 75% epoxy resin. The has many advantages over conventional glass fiber and other composition 20% sisal fiber10% flax fiber, 70% epoxy inorganic materials. Strength of the material which is resin and in another composition 20% sisal fiber,15% flax prepared using epoxy resin with natural sisal and flax fiber, 65% epoxy resin as taken. fibers is mainly depend on the composition based on which matrix and reinforcement being added. -

Preparation and Characterization of Flax, Hemp and Sisal Fiber-Derived

Research Article Adsorption Science & Technology Preparation and 2018, Vol. 36(1–2) 441–457 ! The Author(s) 2017 DOI: 10.1177/0263617417700635 characterization of flax, journals.sagepub.com/home/adt hemp and sisal fiber-derived mesoporous activated carbon adsorbents Melike Dizbay-Onat Center for Community Outreach Development (CORD), College of Arts and Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA Uday K Vaidya Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Biomedical Engineering, Department of Materials Science & Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA Jo Anne G Balanay Environmental Health Sciences Program, Department of Health Education and Promotion, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA Claudiu T Lungu Department of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA Abstract The first aim of this study was to investigate mesoporous activated carbon adsorbents from sisal, hemp, and flax fibers by cost-effective methods. Fibers were impregnated with low concentration (20 wt.%) phosphoric acid. Carbonization temperatures were defined by thermal analysis. Bast fibers (hemp, flax) decompose at lower temperatures (419.36C, 434.96C) than leaf fibers (sisal, 512.92C). The second aim was to compare bast and leaf fibers-derived activated carbon adsorbents by determining physical adsorption properties, chemical compositions, scanning electron microscope, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Results showed that natural fibers have good candidates to prepare mesoporous activated carbon adsorbents with high surface area (1186–1359 m2/g), high mesopore percentage (60–72%), and high C content (80–86%). Even though leaf-derived activated carbon developed more mesoporous structure 2 (72%), bast-derived activated carbons provided higher surface areas (Shemp ¼ 1359 m /g; 2 Sflax ¼ 1257 m /g) and C content. -

Flexform Brochure

® THE LEADER IN NATURAL FIBER COMPOSITES THE LEADER IN NATURAL FIBER COMPOSITES Leading the Way FlexForm Technologies is the North American leader in the man- ufacture of natural fiber composite (NFC) materials made from sustainable resources. Our state-of-the-art facility in Elkhart, Indiana manufactures FlexForm®, a combination of natural fibers such as kenaf, hemp, flax, jute and sisal blended with thermo- plastic polymers such as polypropylene and polyester. FlexForm Technologies is answering the call for lighter weight Absorbancy Products Commercial Equipment materials that meet or surpass the performance requirements of numerous industries including automotive, recreational vehicle, truck, modular housing, packaging, construction, marine, office interiors, agriculture and aviation. Current applications include door panels, consoles, headliners, inserts, package trays, pillars, seat backs, trunk liners, office panels, ceiling tiles, and absorbency products. The Time for Change is Now Global consumption of reinforced plastics is growing at a rate of almost 20% per year. Glass fiber-reinforced plastics (GRP) repre- sent the largest segment of this market. However GRP and wood flour reinforced plastics tend to be heavy, brittle, present envi- ronmental challenges in the workplace, and are difficult to recy- cle. Government regulations coupled with the rising costs of waste disposal are creating significant market demand for high performance, more Eco-friendly alternatives. FlexForm is ideal for seatback applications with FlexForm is the alternative. It is a stronger, more superior properties for knee impact and one-step versatile product providing superior performance compared to processing that allow easy conformance to frame other existing materials. It is no coincidence that our year-over- work geometry, bonding of cover materials, back side year growth has been significant as manufacturers continue to attachments, and trimming in a single operation. -

Cotton: the Fabric of Our Lives

Cotton: The Fabric of Our Lives By Angela Box Oils, balls, swabs, bandages, tissue, paper, napkins, diapers, socks, underwear, shirts, shorts, sweaters, pants, coats, towels, linen, cushions, drapery, upholstery, rugs, carpet, comforters, mattresses, insulation, filtration, and many other things that are used daily by everyone are composed of, or inspired by cotton. Cotton is a soft, fluffy, naturally occurring fiber plant that can be processed into an array of materials and goods. Many, many things that we wear, sleep on, sleep under, walk on, or utilize in wound-care, etc., contain some percentage of cotton. It is a fiber that is used everyday, by everyone, in one way or another. It has qualities that have made it a choice crop for centuries around the world. Today though, cotton is being largely displaced by synthetic fibers that have qualities that exceed the natural crop plant. These fibers can also be mass-produced and sold at relatively lower costs. Still, cotton stands alone as the most utilized fiber crop plant used around the world. Also known as "King Cotton," in the United States, it was the major force behind the institution of the American age of slavery, and cotton prevailed as the economic source for the southern states of the United States and its antebellum prosperity before the civil war. It holds an important place in America's past, present, and future. Cotton is truly the "Fabric of Our Lives". Characteristics Cotton is an annual, biennial or perennial plant, but in cultivation it is generally treated as an annual; herbaceous to short shrub or small tree - two to six feet tall. -

Product Environmental Footprint Category Rules (PEFCR) T-Shirts

Product Environmental Footprint Category Rules (PEFCR) T-shirts Sandrine Pesnel*, Jérôme Payet* on behalf of the Technical Secretariat of the T-shirts PEFCR pilot * CYCLECO, 18, av. Roger Salengro 01500 Amberieu en Bugey - France Version 1.0 February 2019 Valid until 31st December 2020 Page | 1 Table of contents ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................................................. 4 DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1 INTRODUCTION 14 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE PEFCR 14 2.1 TECHNICAL SECRETARIAT .................................................................................................................................. 14 2.2 CONSULTATIONS AND STAKEHOLDERS ................................................................................................................ 15 2.3 REVIEW PANEL AND REVIEW REQUIREMENTS OF THE PEFCR .................................................................................. 17 2.4 REVIEW STATEMENT ........................................................................................................................................ 18 2.5 GEOGRAPHIC VALIDITY ..................................................................................................................................... 18 2.6 LANGUAGE ................................................................................................................................................... -

Notes on Florida's Endangered and Threatened Plants 1

NOTES ON FLORIDA'S ENDANGERED AND THREATENED PLANTS 1 Nancy C. Coile2 The Regulated Plant Index is based on information provided by the Endangered Plant Advisory Council (EPAC), a group of seven individuals who represent academic, industry, and environmental interests (Dr. Loran C. Anderson, Dr. Daniel F. Austin,. Mr. Charles D. D aniel III, Mr. David M . Drylie, Jr., Ms. Eve R. Hannahs, Mr. Richard L. Moyroud, and Dr. Daniel B. Ward). Rule Chap. 5B-40, Florida Administrative Code, contains the "Regulated Plant Index" (5B-40.0055) and lists endangered, threatened, and commercially exploited plant species for Florida; defines the categories; lists instances where permits may be issued; and describes penalties for vio lations. Copies of this Rule may be obtained from Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, P. O. Box 147100, Gainesville, Fl 32614-7100. Amended 20 September 2000, the "Regulated Plant Index" contains 415 endangered species, 113 threatened species, and eight commercially exploited species. Descriptions of these rare species are often difficult to locate. Florida does not have a single manual covering the flora of the entire state. Long and Lakela s manual (1971) focuses on the area south of Glades County; Clewell (1985) is a guide for the Panhandle; and Wunderlin (1998) is a guide for the entire state of Florida but lacks descriptions. Small (1933) is an excellent resource, but must be used with great care since the nomenclature is outdated and frequently disputed. Clewell (1985) and Wunderlin (1998 ) are guides with keys to the flora, but lack species descriptions. Distribution maps (Wund erlin and Hansen, 200 0) are available over the Internet through the University of South Florida Herbarium [www.plantatlas.usf.edu/].