Mermin's Suggestion and the Nature of Bohr's Action-At-A-Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Quantum Spin Correlations of Relativistic Electron Pairs

Study of quantum spin correlations of relativistic electron pairs Project status Nov. 2015 Jacek Ciborowski Marta Włodarczyk, Michał Drągowski, Artem Poliszczuk (UW) Joachim Enders, Yuliya Fritsche (TU Darmstadt) Warszawa 20.XI.2015 Quantum spin correlations In this exp: e1,e2 – electrons under study a, b - directions of spin projections (+- ½) 4 combinations for e1 and e2: ++, --, +-, -+ Probabilities: P++ , P+- , P-+ , P- - (ΣP=1) Correlation function : C = P++ + P-- - P-+ - P-+ Historical perspective • Einstein Podolsky Rosen (EPR) paradox (1935): QM is not a complete local realistic theory • Bohm & Aharonov formulation involving spin correlations (1957) • Bell inequalities (1964) a local realistic theory must obey a class of inequalities • practical approach to Bell’s inequalities: counting aacoincidences to measure correlations The EPR paradox Boris Podolsky Nathan Rosen Albert Einstein (1896-1966) (1909-1995) (1979-1955) A. Afriat and F. Selleri, The Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen Paradox (Plenum Press, New York and London, 1999) Bohm’s version with the spin Two spin-1/2 fermions in a singlet state: E.g. if spin projection of 1 on Z axis is measured 1/2 spin projection of 2 must be -1/2 All projections should be elements of reality (QM predicts that only S2 and David Bohm (1917-1992) Sz can be determined) Hidden variables? ”Quantum Theory” (1951) Phys. Rev. 85(1952)166,180 The Bell inequalities J.S.Bell: Impossible to reconcile the concept of hidden variables with statistical predictions of QM If local realism quantum correlations -

Quantum Eraser

Quantum Eraser March 18, 2015 It was in 1935 that Albert Einstein, with his collaborators Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, exploiting the bizarre property of quantum entanglement (not yet known under that name which was coined in Schrödinger (1935)), noted that QM demands that systems maintain a variety of ‘correlational properties’ amongst their parts no matter how far the parts might be sepa- rated from each other (see 1935, the source of what has become known as the EPR paradox). In itself there appears to be nothing strange in this; such cor- relational properties are common in classical physics no less than in ordinary experience. Consider two qualitatively identical billiard balls approaching each other with equal but opposite velocities. The total momentum is zero. After they collide and rebound, measurement of the velocity of one ball will naturally reveal the velocity of the other. But the EPR argument coupled this observation with the orthodox Copen- hagen interpretation of QM, which states that until a measurement of a par- ticular property is made on a system, that system cannot, in general, be said to possess any definite value of that property. It is easy to see that if dis- tant correlations are preserved through measurement processes that ‘bring into being’ the measured values there is a prima facie conflict between the Copenhagen interpretation and the relativistic stricture that no information can be transmitted faster than the speed of light. Suppose, for example, we have a system with some property which is anti-correlated (in real cases, this property could be spin). -

Required Readings

HPS/PHIL 93872 Spring 2006 Historical Foundations of the Quantum Theory Don Howard, Instructor Required Readings: Topic: Readings: Planck and black-body radiation. Martin Klein. “Planck, Entropy, and Quanta, 19011906.” The Natural Philosopher 1 (1963), 83-108. Martin Klein. “Einstein’s First Paper on Quanta.” The Natural Einstein and the photo-electric effect. Philosopher 2 (1963), 59-86. Max Jammer. “Regularities in Line Spectra”; “Bohr’s Theory The Bohr model of the atom and spectral of the Hydrogen Atom.” In The Conceptual Development of series. Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 62- 88. The Bohr-Sommerfeld “old” quantum Max Jammer. “The Older Quantum Theory.” In The Conceptual theory; Einstein on transition Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, probabilities. 1966, pp. 89-156. The Bohr-Kramers-Slater theory. Max Jammer. “The Transition to Quantum Mechanics.” In The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 157-195. Bose-Einstein statistics. Don Howard. “‘Nicht sein kann was nicht sein darf,’ or the Prehistory of EPR, 1909-1935: Einstein’s Early Worries about the Quantum Mechanics of Composite Systems.” In Sixty-Two Years of Uncertainty: Historical, Philosophical, and Physical Inquiries into the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Arthur Miller, ed. New York: Plenum, 1990, pp. 61-111. Max Jammer. “The Formation of Quantum Mechanics.” In The Schrödinger and wave mechanics; Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: Heisenberg and matrix mechanics. McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 196-280. James T. Cushing. “Early Attempts at Causal Theories: A De Broglie and the origins of pilot-wave Stillborn Program.” In Quantum Mechanics: Historical theory. -

A WORLD WITHOUT CAUSE and EFFECT Logic-Defying Experiments Into Quantum Causality Scramble the Notion of Time Itself

A WORLD WITHOUT CAUSE AND EFFECT Logic-defying experiments into quantum causality scramble the notion of time itself. BY PHILIP BALL lbert Einstein is heading out for his This finding1 in 2015 made the quantum the constraints of a predefined causal structure daily stroll and has to pass through world seem even stranger than scientists had might solve some problems faster than con- Atwo doorways. First he walks through thought. Walther’s experiments mash up cau- ventional quantum computers,” says quantum the green door, and then through the red one. sality: the idea that one thing leads to another. theorist Giulio Chiribella of the University of Or wait — did he go through the red first and It is as if the physicists have scrambled the con- Hong Kong. then the green? It must have been one or the cept of time itself, so that it seems to run in two What’s more, thinking about the ‘causal struc- other. The events had have to happened in a directions at once. ture’ of quantum mechanics — which events EDGAR BĄK BY ILLUSTRATION sequence, right? In everyday language, that sounds nonsen- precede or succeed others — might prove to be Not if Einstein were riding on one of the sical. But within the mathematical formalism more productive, and ultimately more intuitive, photons ricocheting through Philip Walther’s of quantum theory, ambiguity about causation than couching it in the typical mind-bending lab at the University of Vienna. Walther’s group emerges in a perfectly logical and consistent language that describes photons as being both has shown that it is impossible to say in which way. -

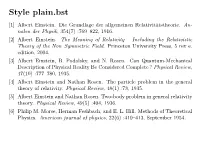

Style Plain.Bst

Style plain.bst [1] Albert Einstein. Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. An- nalen der Physik, 354(7) :769–822, 1916. [2] Albert Einstein. The Meaning of Relativity – Including the Relativistic Theory of the Non–Symmetric Field. Princeton University Press, 5 rev e. edition, 2004. [3] Albert Einstein, B. Podolsky, and N. Rosen. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete ? Physical Review, 47(10) :777–780, 1935. [4] Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen. The particle problem in the general theory of relativity. Physical Review, 48(1) :73, 1935. [5] Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen. Two-body problem in general relativity theory. Physical Review, 49(5) :404, 1936. [6] Philip M. Morse, Herman Feshbach, and E. L. Hill. Methods of Theoretical Physics. American journal of physics, 22(6) :410–413, September 1954. Style abbrv.bst [1] A. Einstein. Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Annalen der Physik, 354(7) :769–822, 1916. [2] A. Einstein. The Meaning of Relativity – Including the Relativistic Theory of the Non–Symmetric Field. Princeton University Press, 5 rev e. edition, 2004. [3] A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, and N. Rosen. Can Quantum-Mechanical Des- cription of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete ? Physical Review, 47(10) :777–780, 1935. [4] A. Einstein and N. Rosen. The particle problem in the general theory of relativity. Physical Review, 48(1) :73, 1935. [5] A. Einstein and N. Rosen. Two-body problem in general relativity theory. Physical Review, 49(5) :404, 1936. [6] P. M. Morse, H. Feshbach, and E. L. Hill. Methods of Theoretical Physics. American journal of physics, 22(6) :410–413, Sept. -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor Nathan Rosen and Black Judaism. Merzbacher has informed There is another advantage of tablet Mountain me that Professor Rosen used to apps which, being unfamiliar with Thank you for your excellent article return to Chapel Hill during the sum- them, the author doesn’t anticipate: in the February 2013 Notices on von mers where he collaborated with Merz- no matter how many blackboards Neumann and the book review of bacher on various research projects. are available, total space is limited, Transcending Tradition. Having been but the apps can store an unlimited educated in North Carolina, I was —Paul F. Zweifel number of handwritten screens. If an especially interested in the discus- Virginia Tech (emeritus) audience member wants a copy of the sion of Black Mountain College in [email protected] notes after a talk, I can either print a the latter. One prominent faculty copy or email the stored document. member there not mentioned in the (Received January 22, 2013) The apps can even record audio from review was the Jewish physicist (and In Defense of Technology for the presentation. disciple of Einstein) Nathan Rosen. Mathematical Talks I think what the author observes about use of computer-based slides Although I earned my Ph.D. in phys- In response to V. V. Peller’s com- today represents not a failure of the ics at Duke University, I was allowed mentary, “Utilization of technology computer as a platform for the pre- to take courses at the University of for mathematical talks: An alarming sentation, but rather inadequately North Carolina in Chapel Hill. -

Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered

Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered incomplete? Gilles Brassard Andr´eAllan M´ethot D´epartement d’informatique et de recherche op´erationnelle Universit´ede Montr´eal, C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville Montr´eal (QC), H3C 3J7 Canada {brassard, methotan}@iro.umontreal.ca 13 June 2005 Abstract In loving memory of Asher Peres, we discuss a most important and influential paper written in 1935 by his thesis supervisor and men- tor Nathan Rosen, together with Albert Einstein and Boris Podolsky. In that paper, the trio known as EPR questioned the completeness of quantum mechanics. The authors argued that the then-new theory should not be considered final because they believed it incapable of describing physical reality. The epic battle between Einstein and Bohr arXiv:quant-ph/0701001v1 30 Dec 2006 intensified following the latter’s response later the same year. Three decades elapsed before John S. Bell gave a devastating proof that the EPR argument was fatally flawed. The modest purpose of our paper is to give a critical analysis of the original EPR paper and point out its logical shortcomings in a way that could have been done 70 years ago, with no need to wait for Bell’s theorem. We also present an overview of Bohr’s response in the interest of showing how it failed to address the gist of the EPR argument. Dedicated to the memory of Asher Peres 1 Introduction In 1935, Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published a paper that sent shock waves in the physics community [5], especially in Copenhagen. -

Introduction to Regge and Wheeler “Stability of a Schwarzschild Singularity”

September 24, 2019 12:14 World Scientific Reprint - 10in x 7in 11643-main page 3 3 Introduction to Regge and Wheeler “Stability of a Schwarzschild Singularity” Kip S. Thorne Theoretical Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA 1. Introduction The paper “Stability of a Schwarzschild Singularity” by Tullio Regge and John Archibald Wheeler1 was the pioneering formulation of the theory of weak (linearized) gravitational perturbations of black holes. This paper is remarkable because black holes were extremely poorly understood in 1957, when it was published, and the very name black hole would not be introduced into physics (by Wheeler) until eleven years later. Over the sixty years since the paper’s publication, it has been a foundation for an enormous edifice of ideas, insights, and quantitative results, including, for example: Proofs that black holes are stable against linear perturbations — both non-spinning • black holes (as treated in this paper) and spinning ones.1–4 Demonstrations that all vacuum perturbations of a black hole, except changes of its • mass and spin, get radiated away as gravitational waves, leaving behind a quiescent black hole described by the Schwarzschild metric (if non-spinning) or the Kerr metric (if spinning).5 This is a dynamical, evolutionary version of Wheeler’s 1970 aphorism “a black hole has no hair”; it explains how the “hair” gets lost. Formulations of the concept of quasinormal modes of a black hole with complex • eigenfrequencies,6 and extensive explorations of quasinormal-mode -

Mad Genius Or Rotten Apple? Exploring Time Travel Through Wormholes

Mad Genius or Rotten Apple? Exploring Time Travel Through Wormholes Gayatri Dhavan “They had to travel into the past to save the future”— Timeline (2003) That’s the tagline from the 2003 movie Timeline. The film itself was forgettable but it was based on a premise that has intrigued humanity for generations: time travel. In the movie, characters were able to identify a wormhole, which allowed time travel between present day and medieval France. I thought this was an interesting idea but I knew it bordered on ridiculous, so I decided to take a closer look at whether time travel through wormholes could indeed be possible. First things first, what is a wormhole? Here is an easy way to picture wormholes without a Physics PhD: imagine that you fold a piece of paper so that one end hovers a couple of inches above the other end. Now punch a hole with a pen on the top part of the paper so the point of the pen reaches the lower part of the paper. Your pen now represents the wormhole. In principle, the wormhole could be used as a shortcut so that, from the point of view of observers outside of the wormhole, travel between the two points could appear to take place faster than the speed of light. The essence of the idea was originally put forth in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen, who suggested the possibility of “bridges” in the space-time continuum. Once I learned that Einstein had something to do with the concept behind wormholes, I actually felt that wormholes might not be so ridiculous after all. -

QUANTUM ENTANGLEMENT and Locality

QUANTUM ENTANGLEMENT and lOcalitY * Miriam Blaauboer , * Kavli Institute of Nanoscience, Delft University of Technology, Lorentzweg 1, 2628 CJ Delft, The Netherlands * E-mail: [email protected] * DOI: 10.1051/ epn /2010602 Can a measurement at location A depend on events taking place at a distant location B, too far away for the information to be transmitted between the two? It does seem too mysterious to be true. Even Einstein did not believe so. But experiments seem to prove him wrong. t is well-known that until the end of his life Einstein was at B travelling at the speed of light cannot possibly reach ᭡ John Bell dissatisfied with quantum mechanics as a fundamental A before the measurement at A has been performed. thinking - ahead of his theory [1]. He strongly believed that the real world eories satisfying both of these criteria are called‘local’ time - about should consist of “systems” (particles, fields) that pos - and‘realistic’. Quantum mechanics, in contrast with ear - Bell tests with I electrons in sess objective properties, i.e. , properties that do not lier developed classical theories, does not satisfy either nanomaterials depend on measurements by external observers. A second of these criteria: properties of a quantum-mechanical essential aspect of these objective properties is that the system do depend on the experimental conditions outcome of a measurement at location A cannot depend under which they are measured, and a measurement at on events taking place at another location B, if B is suffi - A can be influenced instantaneously by an event happe - ciently far away from A that information about the event ning at B via the mechanism called entanglement (see III EPN 41/6 17 Article available at http://www.europhysicsnews.org or http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/epn/2010602 fEaturEs quaNtum ENtaNglEmENt III box). -

Required Readings

HPS/PHIL 687 Fall 2003 Historical Foundations of the Quantum Theory Required Readings: Topic: Readings: Planck and black-body radiation. Martin Klein. “Planck, Entropy, and Quanta, 1901- 1906.” The Natural Philosopher 1 (1963), 83-108. Einstein and the photo-electric effect. Martin Klein. “Einstein’s First Paper on Quanta.” The Natural Philosopher 2 (1963), 59-86. The Bohr model of the atom and spectral series. Max Jammer. “Regularities in Line Spectra”; “Bohr’s Theory of the Hydrogen Atom.” In The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 62-88. The Bohr-Sommerfeld “old” quantum theory; Max Jammer. “The Older Quantum Theory.” In Einstein on transition probabilities. The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 89-156. The Bohr-Kramers-Slater theory. Max Jammer. “The Transition to Quantum Mechanics.” In The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 157-195. Bose-Einstein statistics. Don Howard. “‘Nicht sein kann was nicht sein darf,’ or the Prehistory of EPR, 1909-1935: Einstein’s Early Worries about the Quantum Mechanics of Composite Systems.” In Sixty-Two Years of Uncertainty: Historical, Philosophical, and Physical Inquiries into the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Arthur Miller, ed. New York: Plenum, 1990, pp. 61-111. Schrödinger and wave mechanics; Heisenberg and Max Jammer. “The Formation of Quantum matrix mechanics. Mechanics.” In The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 196-280. De Broglie and the origins of pilot-wave theory. James T. Cushing. “Early Attempts at Causal Theories: A Stillborn Program.” In Quantum Mechanics: Historical Contingency and the Copenhagen Hegemony. -

The Dancing Wu Li Masters an Overview of the New Physics Gary Zukav

The Dancing Wu Li Masters An Overview of the New Physics Gary Zukav A BANTAM NEW AGE BOOK BANTAM BOOKS NEW YORK • TORONTO • LONDON • SYDNEY • AUCKLAND This book is dedicated to you, who are drawn to read it. Acknowledgments My gratitude to the following people cannot be adequately expressed. I discovered, in the course of writing this book, that physicists, from graduate students to Nobel Laureates, are a gracious group of people; accessible, helpful, and engaging. This discovery shattered my long-held stereo- type of the cold, "objective" scientific personality. For this, above all, I am grateful to the people listed here. Jack Sarfatti, Ph.D., Director of the Physics/Consciousness Research Group, is the catalyst without whom the following people and I would not have met. Al Chung-liang Huang, The T'ai Chi Master, provided the perfect metaphor of Wu Li, inspiration, and the beautiful calligraphy. David Finkelstein, Ph.D., Director of the School of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology, was my first tutor. These men are the godfathers of this book. In addition to Sarfatti and Finkelstein, Brian Josephson, Professor of Physics, Cambridge University, and Max Jammer, Professor of Physics, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat- Gan, Israel, read and commented upon the entire manu- script. I am especially indebted to these men (but I do not wish to imply that any one of them, or any other of the individualistic and creative thinkers who helped me with this book, would approve of it, page for page, as it is written, nor that the responsibility for any errors or mis- interpretations belongs to anyone but me).